ARCHIVES

Creating the National Library in Saigon (excerpt)

Published on

By

Cindy Nguyen

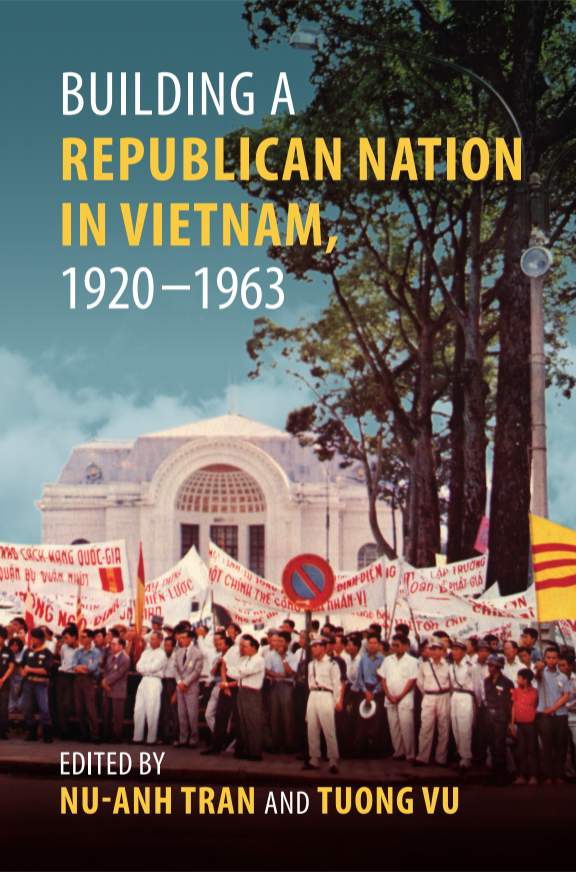

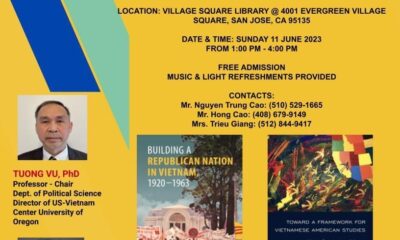

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from chapter 8 of Building a Republican Nation in Vietnam, 1920-1963, edited by Nu-Anh Tran and Tuong Vu, University of Hawaii Press (2022). The text has been redacted for style and readability. Please refer to the volume for the full text. To purchase the volume, please click here.

“Creating the National Library in Saigon: Colonial Legacies, Republican Visions, and Reading Publics, 1946–1958”

This chapter examines the development of the National Library in Saigon from 1946 to 1958 (now the General Sciences Library at 69 Lý Tự Trọng). I argue that government officials and library administrators pursued two intersecting visions of the library as both a national and a public institution. Leaders conceived of it as the protector of national heritage that would assemble and preserve Vietnamese literature, reference works, and historical periodicals. Officials and administrators also envisioned it as a modern, public service of popular education for Saigon urbanites and students. The articulation of these twin functions contributed to the definition of republicanism as both governmental vision and quotidian practices. The institution brought to the surface a wide array of issues that were foundational to republicanism in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) in the 1950s, including the value of public access and civil society, the intertwined processes of decolonization and nation-building, and governmental responsibility to a collective citizenry.

Through tracing the development of the National Library, I shed light on the role of public and cultural institutions in the early RVN. The first part examines the origins of the library from 1946 to 1954 and demonstrates that institutional decolonization was a drawn-out, nonlinear process in which Vietnamese library administrators transformed the colonial Cochinchina Library to serve the reading public. The second part focuses on the logistics of creating a national library system for the RVN from 1954 to 1958. In striving to serve both the Vietnamese nation and the public, the National Library confronted essential questions similar to those that challenged the postcolonial government at large: What is the modern nation of Vietnam? Who is the public and how should the state serve its citizens? The library was not just a symbol of the regime but an institutional articulation of the RVN’s national vision and republican values.

…

This chapter contributes a significant revision to the body of work on libraries by situating the National Library within the larger context of nation-building, decolonization, and the establishment of a republican regime. I argue that the premier library in the RVN was an integral element of Vietnamese nation-building rather than a tool of Western powers. I position my work within the Vietnam-centric turn toward local agency and draw on recent scholarship on the politics, discourse, and practices of nation-building in the RVN.[3] Specifically, my work builds on Nu-Anh Tran’s dissertation “Contested Identities: Nationalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1954–1963)” and Matthew Masur’s dissertation “Hearts and Minds: Cultural Nation-Building in South Vietnam, 1954–1963.”[4] They find that the Saigon regime sought to exert authority over all of Vietnamese culture and, in doing so, asserted political legitimacy across the seventeenth parallel that divided North and South Vietnam. Tran also argues that the government tried to create a single national identity through the creation of cultural institutions and the standardization of the Vietnamese language. Extending these insights, I contend that the National Library was essential to this larger project in the RVN. Officials and administrators conceived of the library as the guardian of Vietnamese culture and sought to unite disparate collections from the colonial period into a centralized national institution.

Although the National Library traced its origins to French colonial libraries, the process of decolonization was never simple nor predetermined. The dismantling of colonial cultural institutions was gradual, and the transfer and regrouping of materials tentative and halting. Moreover, even as the government placed the library in service of nation-building, librarians continued to draw on French library sciences and looked to the French literary world as the cultural standard. A close examination of the National Library also reveals new insight into republican institutions in the RVN. Everyday library users were active agents who facilitated their own individual learning and use of urban public space. They challenged reading room rules and participated within civic discourse by publicly demanding increased access, improved facilities, and Vietnamese-language materials. Thus the institutionalization of republicanism was not a simple top-down process led exclusively by library administrators and government officials. Library users contributed to the development of republicanism in their engagement with public institutions. This chapter demonstrates how colonial legacies, republican visions of nation and public, and changing urban reading publics defined the role of the National Library.

Colonial Legacies, Language Policy, and Division of the Hanoi Colonial Collections, 1946–1954

From the earliest days of French colonialism in Vietnam, colonial officials understood that to build a library was to build the state. The Cochinchina Library (Bibliothèque de Cochinchine, Thơ Viện Nam Kỳ) was first founded in 1865 as an administrative library and information archive for the colonial government, and library users consisted mainly of French and Vietnamese officials. In 1919, it became a public branch of an Indochina-wide network of libraries and archives. Libraries legitimized the authority of the colonial state throughout the Indochinese territories as both a symbol of modernity and control of print circulation. At the same time, library users shaped the everyday function of the library as a space of intellectual nourishment and self-directed education. The Cochinchina Library was housed in the cramped government secretariat building at 34 Lagrandière (later 34 Gia Long, now 159–161 Lý Tự Trọng) together with the central archives of Cochinchina. A popular lending section provided novels to Saigon urbanites, and several book wagons brought thousands of pedagogical texts and novels in French and the romanized Vietnamese script (quốc ngữ) to readers in the Cochinchinese provinces. By 1938, the Reading Room held a collection of more than thirty-six thousand volumes and welcomed more than 133 readers each day despite offering only forty-four seats.[5] The Lending Section recorded a total of thirty-one thousand borrowers and fifty-five thousand book loans that same year. In 1939, the Cochinchina Library designated a small corner of the library as a Children’s Reading Room for young patrons to read books on-site.

Gradual Decolonization, 1946–1954

The decolonization of the Cochinchina Library was a gradual process that reflected the slow progress of decolonization in southern Vietnam. In the fall of 1945, Allied forces arrived in southern Vietnam to disarm the Japanese. The Allies attacked the fledgling Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and assisted French troops in retaking the former colony of Cochinchina. Fighting engulfed the region even before the formal outbreak of the First Indochina War at the end of the following year. For the next decade, Saigon and southern Vietnam emerged as the locus of successive attempts to create an autonomous Vietnamese government, and the shifting status, leadership, and priorities of the old Cochinchina Library mirrored the tentative and halting character of decolonization in the southern third of the country.

In June 1946, a few months after the departure of the Allied forces, the French high commissioner and a handful of Vietnamese politicians established the Provisional Government of the Republic of Cochinchina, a supposedly semiautonomous state in southern Vietnam separate from the DRV. The High Commission signaled Vietnamese semi-autonomy by transferring the Cochinchina Library to the provisional Vietnamese government at the end of the month. The library appears to be one of the first institutions to be transferred and thus was an important symbol of the eventual decolonization of all cultural institutions. Placed within the Service of Education for Southern Vietnam, it was renamed the National Library of Southern Vietnam (Thơ Viện Quốc Gia Nam Việt).[6] Even with the renaming, Vietnamese readers often referred to the library by its various names, including the old colonial name of the Cochinchina Library (Bibliothèque de Cochinchine, Thơ Viện Nam Kỳ), colloquial names such as the Saigon Library (Thơ Viện Saigon), and the new administrative name of the Library of Southern Region or the Library of Southern Vietnam (Thư Viện Nam Phần, Thư Viện Nam Phần Việt Nam). Library administrators and other government bodies often referred to the institution as the National Library since 1946, and it was officially renamed the National Library (Thư Viện Quốc Gia) in 1957. To avoid confusion, I refer to the institution as the National Library for the period from 1946 to 1957 even when the name and status of the library were both in flux. The National Library carried out four primary services: acquisitions, legal deposit, Reading Room, and Lending Section.

…

Đoàn Quan Tấn became the first Vietnamese director of the National Library in February 1948 following the death of French director Rémi Bourgeois. Tấn was active in cultural affairs and Saigon scholarly life. He had been the chairman of the Study Encouragement Society (Hội Khuyến Học) in 1940, a mutual aid society focused on education, the improvement of Vietnamese language, and the study of literature, fine arts, and national history. From 1950 to 1952, Tấn was the chairman of the France-Vietnam People’s Academy Association and the Indochina Archaeology Association; from 1953, he served as the assistant chairman of the French Literary Alliance Association.

In an interview with Radio Saigon in May 1949, Director of the National Library Đoàn Quan Tấn highlighted the mission of the National Library as a public institution.[7] This interview sheds light on the popular use of the libraries even during the politically uncertain transition between 1945 and 1949. Tấn explained that the Reading Room was open all day on Mondays to Saturdays and on Sunday mornings and was “heavily frequented by the Saigonese public such as high school and university students.” The room served an average of eighty readers daily, approximately half of whom were Europeans. Tấn was also proud of the collections and explained that his staff was acquiring new library materials to better serve Vietnamese readers and to encourage greater understanding between Vietnamese and French readers. By 1949, the library held fifty-seven thousand volumes on the humanities, arts, philosophy, religion, and geography; the most popular works among readers were texts about history, the sciences, and law. Because most works were in French, library administrators sought to add more Vietnamese translations of French books on popular science and technology. Administrators also encouraged translation of Vietnamese works into French and recognized translation as an act of political exchange so “that the effort of mutual understanding was not one-sided.” For Đoàn Quan Tấn and other library administrators, it was not enough that the library itself had come under the purview of a Vietnamese government; they believed that even the collection had to undergo a process of decolonization to encourage parity between Vietnamese and French library users.

…

The National Library slowly increased and diversified its collections through purchases, gifts, and mandatory legal deposit of copies of new publications. By 1954, the collection had increased by fifteen thousand works, bringing the total to 79,081 books (6 percent in Vietnamese, 5 percent in Chinese, and 88 percent in French).[10] Yet a closer analysis of the periodicals in the Reading Room reveals an increasing trend to publish periodicals in Vietnamese rather than in French.

Growing Popularity as a Public Library for Vietnamese Readers, 1953–1955

Whereas a substantial number of library users had been European in the late 1940s, the composition shifted to overwhelmingly favor Vietnamese users in the early 1950s. During the same time, the number of total readers steadily increased. In 1953, the monthly average was 1,630, of whom almost 95 percent were Vietnamese. In 1954, the monthly average increased to 2,056, of whom 97 percent were Vietnamese.[11] During this period, the Reading Room offered only forty-four seats, constraining the maximum capacity for reader consultation. Students made up the majority of Vietnamese readers and enjoyed growing clout due to their numbers. In 1954, university students formally requested the administration to shift the opening hours to later in the evening in order to accommodate readers who were busy during the day with school or work. Library administrators honored the students’ request and extended opening hours to nine in the morning until nine at night on Mondays through Saturdays as well as Sunday mornings. Because the Reading Room usually received few readers during lunchtime hours, it now closed for a three-hour break at noon.[12] These adjustments point to the influence of readers to shape library operations.

Ever since the French colonial period, the Lending Section had been more popular than the Reading Room. In March 1944, the Lending Section relocated from Catinat Street to Saigon’s city hall for safekeeping and temporarily closed in 1945 during the August Revolution and subsequent transfer of authority. In 1951, it moved to the Indochinese Circle Association building on 14 Lê Văn Duyệt (formerly 14 Thủ Tướng Thinh, later 194 D Pasteur) in order to accommodate more visitors. In 1954, it welcomed 2,100 readers each month, of whom more than 75 percent were Vietnamese.[13] Fourteen percent were students who often borrowed textbooks. Readers frequently checked out materials from the valuable collection of ten thousand works of literature, science, textbooks, and novels.

End of the First Indochina War and the Transfer of the Hanoi General Library to Saigon, 1954–1955

During the First Indochina War, decolonization entailed the breakup of French Indochina as a single entity. Accordingly, the Indochina-wide Directorate of Archives and Libraries and the former colonial collections in Hanoi, Saigon, Phnom Penh, Huế, and Vientiane were slowly divided between France, the State of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.[14] The Geneva Accords that partitioned Vietnam at the end of the war also marked the formal division of the General Library and Central Archives in Hanoi, the former capital of French Indochina. Between 1954 and 1955, a quarter of the collection of the Hanoi General Library, materials from the University of Hanoi and the Central Archives, and sixteen library and archives personnel were transferred to Saigon. A newspaper article from 1956 noted that at the time of the relocation, the Hanoi library was “considered the largest and most valuable library in Vietnam and judged by other countries as the second greatest in the Far East.”[15] The remaining collections and personnel of the General Library (now renamed the Central Library of Hanoi, or Thư Viện Trung Ương Hà Nội) continued to operate in Hanoi, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

…

Creating a National Library: Organization and Visions, 1954–1958

As early as 1949, the State of Vietnam proposed the development of a new national library on Boulevard Norodom (later Thống Nhất Street, today Lê Duẩn Street) to address the overcrowded facilities inherited from the French colonial government.[18] This proposal made clear that the SVN intended to make libraries part of the government’s effort at cultural nation-building. The new buildings would serve as the cultural capital for the entire country and a grand integration of the colonial and postcolonial library collections. The director of the library, Đoàn Quan Tấn, argued that the Norodom project would “equip Saigon—the capital of South Vietnam and a university city—with a museum-library worthy of it.”[19] The original vision included a cultural center with an archives repository, a two-part library with a central room for study and reference and a lending section intended for youth, and a historical museum of Indochina. The museum would be the most important part of the cultural center and devoted to the work of France in the Far East. That the museum should focus on France and Indochina rather than Vietnam made clear that decolonization was still incomplete and called attention to the ambiguity of the SVN as a national government within the French Union.

With the official end of French claims to authority in Indochina in 1954, the postcolonial state made new plans for a national library of a fully independent Vietnam. The Norodom project rooted in French colonial cultural preservation evolved into a Vietnamese project of decolonization, nation-building, and republican aspirations. In 1955, government officials replaced the Norodom project with an ambitious proposal for a “National Library and Cultural Center” (Thư Viện Quốc Gia và Trung Tâm Văn Hoá) with a 150-seat reading room, an eight-story storage building large enough for at least three-hundred thousand volumes, a cultural center with two lecture rooms, and a stage auditorium that could seat up to a thousand attendees.[20] Furthermore, the grounds of this new complex would include the new National Administration Institute, and the Faculty of Humanities and the Faculty of Law in the University of Saigon. President Ngô Đình Diệm proposed constructing the building on the site of the former Saigon Maison Centrale prison (Tù Khám Lớn) at 69 Gia Long Street (now 69 Lý Tự Trọng) and, on July 3, 1956, inaugurated the building of the National Library and Cultural Center project.

At the bricklaying ceremony marking the beginning of construction in 1968, Secretary of State in Charge of Cultural Affairs Mai Thọ Truyền delivered a speech emphasizing the legacy of the colonial prison and the significance of the library for national culture:

Those tiles and stones of the former prison left on the ground bear witness to the noble sacrifices of those fighting for the nation’s freedom and its culture. The ghosts of these heroes, if any of them are still haunting this site, certainly would be satisfied with our present enterprise which aims at protecting and developing our national culture.[22]

He continued to describe his dream of the new national library as a “meeting center for Eastern and Western cultures as well as a source of information and communication for mankind.” The new National Library would be centrally located in Saigon—at the “heart of the capital and near buildings that represent the power of the nation, such as the Independence Palace, Gia Long Palace, and the Court of Justice.”[23] However, due to economic difficulties and political instability, plans to build a centralized institution fragmented into separate building projects in different parts of the city. Construction of a new building for the National Library officially began in 1968 at 69 Gia Long Street, and the location was not opened until December 23, 1971.[24]

National Ambitions and Colonial Legacies

On June 26, 1954, Phan Vô Kỵ, the assistant director of the Service of Library and Archives of Southern Vietnam, summarized library services from the time of French handover in 1946 to the time of writing.[25] Kỵ noted that the National Library of Southern Vietnam continued to carry out its essential services even with a severe deficit in personnel and budget. Three library personnel had been conscripted for the war, and the budget was inadequate for the size of the library and demands from readers. Kỵ argued that the library must advance into a fully functional institution that was worthy of the capital of an independent Vietnam:

With the complete independence of our motherland and the designation of Saigon as the national capital, the National Library is far too small to provide services for the Saigon population of over two million. The library is too crowded, unable to store books and documents shipped to the library. With only forty-six chairs in the Reading Room, some readers come to the library but end up leaving due to lack of seating. The estimated annual budget of the library is not enough to purchase books or several copies of certain books in order to let readers check out the books to read at home. The hope is that the National Library will be able to expand and provide the same level of conveniences and services as other large libraries of civilized and modern countries. The National Library must become a space worthy to collect the spiritual artifacts of a people with four thousand years of civilization.[26]

For Kỵ, the National Library carried two primary tasks: the preservation of Vietnamese cultural heritage and a public service to the growing population of Saigon. Although he used a vague benchmark of “civilized and modern countries” to evaluate the capabilities of the library, it is significant that he depicted the library as both an everyday institution serving the public and a symbol of nationhood.

In the nine-page plan titled “Organization of the National Library” (“Tổ chức Thơ Viện Quốc Gia”), Lê Ngọc Trụ outlined the importance of library collections and methodic organization.[27] The self-taught linguist Lê Ngọc Trụ (1909–1979) worked in the National Library in Saigon from 1948 to 1961 as deputy secretary and then as director of the collections department from 1961 to 1964. Like other administrators, Trụ was an intellectual in his own right outside his work for the library. Trụ self-studied Vietnamese linguistics, published in the newspapers Đông Dương (1939–1941), Đọc (1939), Nghệ thuật (1941), Bút mới (1941), and was an active member of the Study Encouragement Society of Southern Vietnam (Hội Khuyến Học Nam Kỳ). In 1954, Trụ became the director of the Institute of History and later worked as a linguistics professor at the University of Arts and University of Pedagogy in Saigon. He declared that the National Library must not be merely a “storage space of books” but must also be systematically organized for ease of reader access, research, and use.[28] “Books and newspapers are the foundation of the library,” Trụ proclaimed. “We cannot call our library a proper institute with such a large number of books in the library organized without a rational order; with the increasing number of print media published each day, we cannot blindly purchase texts for the library without selective intention.” Trụ believed that the first stage of library organization required reassessing the collections (thâu thập sách báo) and that the later stages included organization (sắp đặt) and preservation of materials (gìn giữ sách báo).

The Public Library Mission: “To Inform, to Educate, and to Entertain”

Vietnamese administrators sought to define the National Library as a public library in addition to a national institution. A lengthy report titled “La Bibliothèque Nationale du Sud-Vietnam,” written in 1956 by a library administrator, ambitiously declared the institution to be “a library of information and general culture. With a collection of selectively chosen books and intended for the public, the library has a three-part goal like all public libraries: to inform, to educate, and to entertain.”[29] The public function of the National Library made it distinctly modern and distinguished it, according to the report, from previous libraries that had existed in Vietnam. The author briefly summarized the history of libraries prior to French colonialism and noted that private libraries and the royal court maintained literary works and documents written in classical Chinese during the Lý and Trần dynasties (eleventh to fourteenth centuries). Later, the French colonial government established the library and archives in Cochinchina for documentation purposes, the report added. In highlighting the differences between the National Library and its predecessors, the author made a temporal distinction between private or administrative libraries of the past and the national public library of the future.

…

Although administrators and foreign readers still relied on the library, university students now made up the majority of users. This shift in clientele reflected the expansion of higher education in the RVN due to the relocation of the University of Hanoi and the most prestigious high schools in Hanoi to Saigon. Further, the overall increase of library users mirrored the rising Vietnamese-language literacy rates and rapidly increasing population of Saigon.

The library administrator argued that acquisitions of new books and periodicals should align with the needs of its changing readers as well as the three-part mission of a public library to inform, educate, and entertain. The author elaborated on the importance of selective acquisitions based on reader behavior:

In other words, acquisitions must respond to the public’s demand for information and above all operate as a public service to enable the public to do their work through access to documentation. The new acquisitions must also help students who are preparing for their exams or their research in a specific field. Lastly, the new acquisitions must provide good reading matter for the other frequent patrons of the library: novels of undisputed literary and moral value and good works of scientific popularization. In all ways possible, the library is enriched with good works in its collections. The library strives to complete its existing collections. It also creates new major collections of general culture and information, not just specialty works of this or that scientific branch.

The purposeful acquisitions of varied reading matter suggests that administrators framed the library as a public resource and supplementary education for the increasingly diverse reading publics, including Vietnamese students, administrators, foreign researchers, and general readers.

The General Library at Pétrus Ký and Serving Cholon Readers, 1955–1958

While awaiting the construction of the National Library and Cultural Center, the materials from Hanoi remained in a storage facility in Khánh Hội near the Saigon River because the colonial library building at 34 Gia Long was not large enough to receive the seven hundred boxes. In 1955, the abandoned refectory hall of the Pétrus Ký School on Nancy Street (today Nguyễn Văn Cừ Street) was designated as a temporary library for the transferred collection. The temporary library was often referred to as the General Library (Tổng Thơ Viện) or the National Library at Pétrus Ký. The General Library was placed under the management of the University of Saigon (Viện Đại Học Sài Gòn).

…

Not until 1957 did the library obtain an approved budget to purchase essential supplies and officially open to the public. The report commended the “dedication and hard work of Nguyễn Hùng Cường (the head manager of the storage depot) who emphasized the importance of technical standards, books, and furniture.” Under Cường’s management, twenty-five thousand items of the transferred collection were finally incorporated into the Pétrus Ký location and accessible to the public. Cường reported regretfully that only a seventh of the boxed-up books had been opened, cataloged, and put in circulation by June 1957. Many of the commonly used reference books were in poor condition, Cường observed, and needed to be rebound. Further, the library had only a limited number of tables and chairs, for a maximum of forty readers.[32]

Decree 544/GD/CL, dated June 20, 1957, officially placed the General Library under the direct administration of the RVN Ministry of National Education. The General Library merged with the existing National Library of Southern Vietnam on Gia Long Street to form a centralized and similarly named National Library system that would function as the model for other libraries in the country.[33] The National Library system was integrated into the new Central Library and Archives of Vietnam (Thơ Viện và Văn Khố Trung Ương Việt Nam), which controlled all libraries, archives, and national legal deposit.[34] During this time, the National Library system comprised three locations scattered across Saigon: the reading and consultation library at 34 Gia Long still known as the National Library (formerly the Cochinchina Library), the General Library located at Pétrus Ký School (transferred materials from Hanoi), and the temporarily closed Lending Section and Children’s Reading Room at 194D Pasteur.

…

The librarian-archivists at Pétrus Ký library argued that their current location served the large intellectual community of Cholon:

After evaluating the Pétrus Ký library, we recognize that this library has already been organized with the most appropriate and advanced methods. The number of library readers has been increasing each day—intellectuals of the large and crowded Cholon region (and the neighboring universities such as the Faculty of Sciences [in the University of Saigon], Pétrus Ký School, Chu Văn An School, and the Military University) often visit the library. The library has a great number of valuable reading matter that benefit readers when they are looking for specific information or reading books and newspapers to entertain their spirits. The Pétrus Ký library has forty seats for readers. Thus, in the meantime while we await the construction of the new National Library and Cultural Center, we propose to use the Pétrus Ký library to serve Cholon intellectuals and, more generally, all those who are thirsty for knowledge.

By 1958, the Pétrus Ký library received an estimated number of 2,148 readers in April and 2,780 in June, averaging 109 readers each day.[36] It received new books in Vietnamese, French, and English donated from other departments, associations, and research institutes. For example, the US Information Service donated Ketchum Richard’s “What Is Communism,” “Việt Mỹ” (pamphlets from the Office of the Vietnam-American Association), UNESCO’s Des bibliothèques publiques pour l’Asie, and Bulletin of the National Academy of Library Administration (Tập san Học Viện Quốc Gia Hành Chánh Thư Viện).

The Disorganized National Library on Gia Long Street and the Demand for Lending Services, 1957–1958

From 1946 to 1958, the National Library system existed in a transitional three-part organization and struggled to serve the increasing population of Saigon-Cholon readers. The National Library at 34 Gia Long Street inherited the collections from the old Cohinchina Library, including Indochinese and French historical periodicals such as the Revue indochinoise, Bulletin de l’Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient, and Bulletin des amis du Vieux Hué. This initial collection, however, did not include popular Vietnamese-language periodicals such as Nam phong, Tri tân, and Đông Dương tạp chí, and the serials it did include were often incomplete.[37] The National Library at Gia Long Street continued earlier efforts to expand its collection and actively requested books and serials on contemporary politics, science, libraries, and economics from France, new books from America, and other contemporary international works. Additionally, many libraries and institutions from across the world such as UNESCO, the French national bibliography, and the Michigan State University Vietnam Advisory Group donated many works to the National Library.[38]

Attempts to build the library collection through legal deposit encountered severe limitations. Standardized requirements for legal deposit of new publications had not yet been implemented since 1944. Phan Vô Kỵ, who replaced Đoàn Quan Tấn as the director of the library in July 1957, sent regular demands to newspapers, publishers, and institutions to figure out incomplete publication information. Correspondence documents point to how Kỵ individually tracked down publishers to determine where their works were officially printed and whether they had been filed into legal deposit.[39] By 1957, of a total of 1,946 legal deposits, 1,562 were nonperiodical Vietnamese works; only 132 were French works.[40] Additionally, in 1957 the number of legal deposits in other languages as well as bilingual or trilingual works was substantial: English (98), Vietnamese-English (80), Vietnamese-French (26), Vietnamese-Chinese (32), English-Chinese (4), and Vietnamese-French-English (2). Periodical legal deposits were mainly Vietnamese (833), though some were in other languages: French (60), English (39), Vietnamese-English (49), Vietnamese-French (13), and Vietnamese-Chinese (12). The number of legal deposits in various languages points to the extensive multilingual publishing industry and reading publics of Saigon-Cholon in the 1950s. Further, many works in the library were Vietnamese translations from French translations of other language books, such as Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind or Carlo Lorenzini’s Italian-language Pinocchio.[41]

Several readers publicly complained about the library’s limited services and space. Despite claims that the Lending Section on Pasteur Street would soon reopen, it remained closed to the public and the building was occupied by governmental offices. In 1956, the newspaper Dân chủ published a letter from “a few soldiers and civil servants” urging the Ministry of National Education to find a location where it could reopen the Lending Section.[45] The Lending Section remained closed. In April 26, 1957, Đoàn Quan Tấn from the National Library on Gia Long street issued a similar request to the ministry and submitted a copy of the article from Dân Chủ as evidence of popular demand.

Requests for reopening the Lending Section continued throughout the year, including specific demands for a large building, adequate staff, more books, additional furniture, and the transfer of the existing collections out of storage. On April 1958, the Lending Section reopened together with the Children’s Reading Room and was renamed the Lending Library and Children’s Reading Room (Thư Viện Cho Mượn và Phòng Ðọc Thiếu Nhi). It reportedly boasted 13,700 books and a daily average of 115 readers.

Hierarchies of Readers and Library Surveillance

The limited space and resources of the National Library at 34 Gia Long meant that it did not meet the needs of the reading public; and administrators developed policies to restrict access, enforce regulations, and favor certain readers while shutting others out. The growth of the population in Saigon led to increased demand; and the library reported a daily average of two hundred users in the late 1950s, double that during the colonial period. In particular, the expanding number of schools in Saigon produced an ever-growing population of students, who transformed the National Library into a space for studying and socializing. Students were the most ardent and eager readers, actively using the library to access expensive textbooks and reference matter and to supplement classroom materials with valuable periodicals, novels, and translated texts.

…

Students not only competed against each other for space but also crowded out other library users that administrators favored. In a letter to the Ministry of National Education in summer 1957, Phan Vô Kỵ proposed adding more tables and chairs to the Reading Room and opening a researcher’s room with twelve seats. The addition would bring the total number of seats to ninety. Additionally, the creation of a researcher’s room would separate those he considered more serious readers from the rowdy students in the main room. Kỵ also suggested a series of changes to take place after the annual closure of the library from July 15 to August 15.[47] He wanted to create a system of daily reading cards to monitor and limit access based on the number of available seats. Each week, the library would issue 480 access cards, color-coded by day and session (morning or afternoon session). Each day, eight seats would be reserved for infrequent but important readers such as professors and administrators. Kỵ developed this system to restore order to the Reading Room and “to prevent groups of university students from turning the Reading Room into a study room for themselves.” He also wanted “to allow those who wish to consult library materials to not have to push and shove and to guarantee a proper seat for readers . . . and for the library to be able to monitor greedy readers and thieves.”[48]

Clearly, administrators envisioned greater surveillance and discipline of readers. The National Library at Gia Long created new regulations to take place after the annual closure that year. On entering the library, readers now had to provide their card so that the library could collect reader usage statistics. On exiting the Reading Room, all belongings and bags had to be inspected to detect any stolen materials.[49] Further, the regulations included a clause that emphasized the communal and public use of the library: “For the benefit of the collective, the library requests that readers protect the books and newspapers by not writing on them, folding the pages, or overextending the binding.” Readers must also return reference books where they belong “to convenience and not disadvantage other readers.” For the first time, the rules also included a clause that permitted the library to refuse entrance to any reader who “dressed inappropriately or behaved impolitely.” Library users who failed to conform to standards of dress and behavior set by the administrators could be denied access altogether. Library administrators called for a “complete education” for readers, issuing detailed regulations on reader behavior and proper care of library materials.[50] These extensive rules defined proper reader comportment, cultural norms, and the proper use of a modern public library.

The separation of readers into different categories sheds light on the underlying hierarchy of library readers. The complaint of library administrators at 34 Gia Long in the 1950s about the lack of decorum and the crowding out of more serious readers was similar to the discourse on the Hanoi Central Library in the 1920s and 1930s.[51] The distinction between leisure and serious readers and the decision to prioritize the latter reflected a continual debate over the mission of the libraries in Vietnam. Was the National Library a public educational resource for all readers, whether they were students, researchers, or government officials? Should the space be used for study by Vietnamese university students or as a research institution for officials and professors? What should the public read and how should they behave? These questions were central to the visions, development, and organization of the National Library in the RVN.

Conclusion

This chapter examines the slow and fragmented development of the National Library in Saigon from 1946 to 1958. I show how the inheritance of the colonial institutions intersected with decolonization, nation-building, and modernization efforts. In this transitional period, the mission of the library was brought into question. As in the colonial period, the library held tremendous symbolic value of modernity, legitimacy, and state capacity. French colonial practices of library science continued to inform acquisitions and overall library functions. Further, the National Library of the RVN sought to redefine the library as a public, educational resource for its citizens and use the cultural institution to enhance the regime’s position in the contest against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam for national legitimacy.

Administrators of the National Library envisioned a new social, political, and educational mission of the library as both a national and a public institution. They discussed how to transform the largely French-language collections to meet the needs of urban Vietnamese readers. Administrators justified the importance of the library using republican values of state responsibility to provide public services and educational resources to its citizens. The pursuit of a public and national library intersected with the larger decolonizing and nation-building project to create a culturally coherent national identity, a republican government serving a loyal citizenry, and an engaged civil society based in the self-anointed capital of Saigon.

Notes

Chapter 8: Creating the National Library in Saigon

[1] For example, see the retrospective history of the library produced by the staff of National Library of Vietnam every five years: Lê Văn Viết, Nguyễn Hữu Viêm, and Phạm Thế Khang, Thư Viện Quốc Gia Việt Nam—90 năm xây dựng và phát triển (Hanoi: Thư Viện Quốc Gia, 2007); and Thư Viện Quốc Gia Việt Nam: 85 năm xây dựng và trưởng thành, 1917–2002 (Hanoi: Thư Viện Quốc Gia, 2002).

[2] The nationalist narrative of cultural imperialism is most apparent in studies of library development in the RVN, where libraries are framed as part of American cultural imperialism and propaganda. For a schematic comparison of socialist libraries in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and supposedly imperialist libraries in the RVN during the Vietnam War, see Phạm Tân Hạ, “Hoạt động thư viện ở thành phố Sài Gòn thời kỳ 1954–1975” (PhD diss., Trường Đại Học Khoa học Xã hội và Nhân Văn, Ho Chi Minh City, 2005).

[3] This chapter builds on the important scholarship on RVN state and society by Nu-Anh Tran, Van Nguyen-Marshall, Christopher Goscha, Brett Reilly, Edward Miller, Matthew Masur, and Thaveeporn Vasavakul. I especially thank Nu-Anh Tran for sharing her research material and insights to frame my project.

[4] Matthew Masur, “Hearts and Minds: Cultural Nation-Building in South Vietnam, 1954–1963” (PhD diss., Ohio State University, 2004); Masur, “Exhibiting Signs of Resistance: South Vietnam’s Struggle for Legitimacy, 1954–1960,” Diplomatic History 33, no. 2 (April 2009): 293–313; and Nu-Anh Tran, “Contested Identities: Nationalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1954–1963)” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2013).

[5] Rémi Bourgeois, Rapport sur la direction des archives et des bibliothèques (1938–1939) (Hanoi: Imprimerie Le Van Tan, 1939).

[6] Đoàn Quan Tấn’s response to interview questions from Ngôn Luận newspaper, March 26, 1955, Folder 2, National Library of Southern Vietnam Collection (Phông Thư Viện Quốc Gia Nam Việt [TVQGNV]), National Archives Center 2 (Trung Tâm Lưu Trữ Quốc Gia 2 [TTLTQG2]), Ho Chi Minh City.

[7] Đoàn Quan Tấn’s response to interview questions from Radio Saigon, May 1949, Folder 2, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[8] Đoàn Quan Tấn’s response to interview questions from Ngôn Luận newspaper, March 26, 1955, Folder 2, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[9] Lê Ngọc Trụ, “Tổ chức Thơ Viện Quốc Gia,” c. 1954, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[10] “La Bibliothèque nationale du Sud-Vietnam” c. 1956, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[11] “La Bibliothèque nationale du Sud-Vietnam” c. 1956; “Le développement des bibliothèques au Viet-nam de 1953 à 1957,” c. 1957, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[12] “La Bibliothèque nationale du Sud-Vietnam” c. 1956, folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[13] Report from Phan Vô Kỵ to attaché of French information in Southern Vietnam, January 23, 1953, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[14] Conventions, 1949–1953, Folder 2041-05, Direction des Archives et des Bibliothèques (DABI), National Archives Center 1 (Trung Tâm Lưu Trữ Quốc Gia 1 [TTLTQG1]), Hanoi; and Conventions and Statutes, 1953, Folder 60-205, Haut Commissariat de France pour l’Indochine (HCI), Archives Nationale d’Outre-Mer (ANOM), Aix-en-Provence.

[15] “La Bibliothèque générale nationale du Viet-Nam est la seconde bibliothèque de l’Extrême-Orient,” Mouvement de la Révolution Nationale 232 (April 18, 1956), Folder 48, Archives Privées Papiers Boudet (PB), ANOM.

[16] Information on the transfer of collections is compiled from the following sources: Internal reports and inventory lists, 1954–1958, Folder 11, Service of the National Archive Collection (Phông Nha Văn Khố Quốc Gia [NVKQG]), TTLTQG2; and Internal reports, 1957–1958, Folder 12, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[17] Report by Nguyễn Hùng Cường, January 12, 1955, Folder 11, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[18] Đoàn Quan Tấn’s response to interview questions from Radio Saigon, May 1949, Folder 2, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[19] Đoàn Quan Tấn’s response to interview questions from Radio Saigon, May 1949, Folder 2, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[20] Report, March 18, 1955, Folder 2, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[21] Ngô Đình Diệm’s speech at the inaugural ceremony published in Việt Nam Thông Tấn Xã, 1949 (July 3, 1956, afternoon edition), Folder 18141, Office of the President Collection, First Republic (Phông Phủ Tổng Thống Đệ Nhất Cộng Hòa [PTTĐICH]), TTLTQG2.

[22] Speech by Mai Thọ Truyền delivered at the bricklaying ceremony for the National Library, December 28, 1968, found in “Hồ sơ v/v xây cất Thơ Viện Quốc Gia tại 69 Gia Long, Sài Gòn năm 1960–1971, Tập 2: Lễ đặt Viên đá đầu Tiên,” Folder 383, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[23] Speech by Mai Thọ Truyền, 1968, Folder 383, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[24] Internal reports, architectural plans, and proposals, Folders 389 and 382, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[25] Phan Vô Kỵ, “Hoạt động của Thơ Viên Quốc Gia từ khi giao lại cho chánh phủ Việt Nam đến ngày nay,” June 26, 1954, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[26] Phan Vô Kỵ, “Hoạt động của Thơ Viên Quốc Gia từ khi giao lại cho chánh phủ Việt Nam đến ngày nay,” June 26, 1954, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[27] Lê Ngọc Trụ, “Tổ chức Thơ Viện Quốc Gia,” c. 1954, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[28] Lê Ngọc Trụ, “Tổ chức Thơ Viện Quốc Gia,” c. 1954, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[29] “La Bibliothèque nationale du Sud-Vietnam,” May 1956, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[30] “La Bibliothèque nationale du Sud-Vietnam,” May 1956, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[31] “Situation générale, rapport 1956,” Folder 11, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[32] Nguyễn Hùng Cường, “Tờ tường trình về Tổng Thư Viện Quốc Gia,” July 18, 1957, Folder 11, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[33] Nguyễn Hùng Cường, “Tờ tường trình về Tổng Thư Viện Quốc Gia,” July 18, 1957, Folder 11, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[34] “Phúc trình tổng quát, ” c. 1957, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[35] Nguyễn Hùng Cường, Trịnh Huy Đào, Nguyễn Văn Tấn, internal report, December 19, 1957, Folder 11, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[36] “Báo cáo hoạt động và thành tích của Tổng Thơ Viện Quốc Gia Năm, 1954–1958,” Folder 11, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[37] “La Bibliothèque nationale du Sud-Vietnam,” May 1956, Folder 11, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[38] Correspondence and inventory lists, 1957, Folder 7, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[39] Correspondence from Phan Vô Kỵ, 1957, Folder 7, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[40] Statistics of legal deposits and purchases of periodicals at 34 Gia Long, 1957, Folder 10, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[41] Survey on state of translation in Vietnam, July 17, 1957, Folder 7, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[42] “La Bibliothèque nationale du Sud-Vietnam,” May 1956, Folder 102, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[43] Phan Vô Kỵ to Minister of National Education, March 8, 1957, Folder 7, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[44] Internal reports, 1957, Folder 7, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[45] Phan Vô Kỵ to Ministry of National Education, August 2, 1957, Folder 7, NVKQG, TTLTQG2; and “Xin mở thơ viện cho mượn sách đọc,” Tiếng dân kêu column, Dân Chủ, March 21, 1957.

[46] Phan Vô Kỵ to the District 1 Police, Saigon, June 13, 1957, Folder 7, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[47] Phan Vô Kỵ to Ministry of National Education, June 28, 1957, Folder 7, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[48] Phan Vô Kỵ to Ministry of National Education, June 28, 1957, Folder 7, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[49] Library regulations, August 14, 1957, Folder 7, NVKQG, TTLTQG2.

[50] Đoàn Quan Tân’s response to Radio Saigon questionnaire, May 1949, Folder 2, TVQGNV, TTLTQG2.

[51] Cindy Nguyen, “Reading Rules: The Symbolic and Social Spaces of Reading in the Hà Nội Central Library, 1919–1941,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 15, no. 3 (August 2020): 1–35, esp. 17–18.

You may like

-

Library Development In the Republic of Vietnam Before April 30, 1975

-

Striving for a Lasting Peace The Paris Accords and Aftermath

-

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

A Teacher One Day, a Teacher for Life: Memoir of a Vietnamese Librarian

-

Interview with Father Le Ngoc Thanh: Faith can change the world.

-

Upcoming Event: 6/11/23 50 Years of the Vietnamese Community in the US: From History to the Future

Translation: The Decision in 2013 of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Certain Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform

Thủ Đức Demonstration High School: A Modern Educational Policy and Teaching Method of the Republic of Vietnam

Southeast Asia falls into China’s Trans-Asian Railway Network

A Proposed Outline for a Study on Republicanism in Modern Vietnamese History

Tran Le Xuan – Diplomatic Letters

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Politics & Economy1 year agoRethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education