Society & Culture

Interview: On VAYLA and Finding Community with Jacqueline Thanh

Published on

Editor’s Note: The transcript of this interview was edited for readability, and some quotes have been altered to better capture the intent of the interviewee. I have abbreviated my name (Vinh Pham) to VP and Jacqueline Thanh to JT. To learn more about Jacqueline and VAYLA click here.

I first learned about VAYLA through a friend and colleague, Cristina Martínez-Istillarte, a recent PhD graduate of Tulane University who works in the non-profit space in New Orleans. Cristina wanted to know if I was familiar with this Vietnamese organization in the city that was doing really exciting work. Unfortunately, I had never heard of the organization until that moment and began to research it.

Born in the wake of Post-Katrina reconstruction, VAYLA is a community-based non-profit that began by a grass-root initiative to fight against the building of a landfill in Village de l’Est. The movement was led by young members of a community that was historically Vietnamese refugees, who settled in the area after 1975. Since then, the organization has grown substantially, and so has its goals. At the helm is VAYLA’s executive director, Jacqueline Thanh, a kind, empathetic, and determined woman of Vietnamese-Chinese descent.

Jacquline is a San Francisco native, a social worker, a Climate Justice Design Fellow at Harvard, and a recently minted Phd from the University of Southern California in Social Work. Taking the role of executive director since 2019, Jacqueline has seen many shifts in the organization, weathered several evacuations, as well as the pandemic with her team. Upon finding her profile, I knew I wanted to speak with her for AAPI heritage month. In this interview, I sat down with Jacqueline, now Dr. Thanh, to learn more about her journey to finding VAYLA, the challenges ahead for this organization, and what it means to be a minority for working within a minority space.

VP: How did you find your way to VAYLA?

JT: The American South is a fascinating place, slavery, chattel slavery in particular is baked into the soil […] The history of colonialism is so palpable, it’s almost familiar from the Mekong to the Mississippi. So after doing my graduate work in social work and human rights, in trauma informed ways, I was fascinated by how human rights intersected with health administration policy. A lot of my clinical work was based on working with survivors of politically sanctioned torture, so I did therapy with people from Syria, the Congo, and plethora of other countries. But with most of the folks I worked with, I couldn’t not see my parents’ faces.

It’s jarring to me to see the remnants of war in people’s lives and how for generations people try to pick up and try to create a sense of normalcy again. There is something beautiful and brutal about social work being inherently white supremacist, and I recognized that I am a very colonized person with a Western education…Much of this secular accolades have been a search for a sense of safety. So a lot of my academic and professional journey has been how to find the words to articulate how complex trauma informs decisions. I found myself at this particular non-profit five years after being in New Orleans.

My first position was working at the district attorney’s office as a victim advocate working with women who had survived violent felony cases through crimes against women, human trafficking, and I served over nine-hundred families in one year. And I was the only Asian-American social worker in the entire building […] I had not known how Asian I was until I lived in the south. When you’re piecemealing food and growing your own food, you’re like, I’m hella Asian. I still remember finding this job posting, I couldn’t believe it was real. It’s in New Orleans East and it’s very different[…] Like most of the country, due to Catholic charities, refugees were placed there with black and brown folks, after black and brown folks had moved there after white flight.

So VAYLA came about after Katrina, because there was a landfill they were trying to build, which would have displaced a lot of people. And in thinking of repair and rebuilding, they really left black and Asian people out of the map. So there was this really momentous rise to the occasion to stop the landfill from being built […] I came in in 2019, after the executive director, and I like to say you never put a woman in a position of power unless there is a level of clean-up […] We had a lot of repair to do. We’ve had four evacuations since I’ve taken this position and we’ve weathered the pandemic.

The first month I started I found it very emotionally taxing. What changed it for me was when we hosted a Juneteenth event. It was all in person, pre-pandemic, and I invited elders from Little Woods, which is a predominantly black neighborhood. New Orleans East used to host the first black beach during segregation and this is where Vietnamese folks moved into. We had citizenship classes for our Vietnamese elders there and because a lot of them were getting their citizenship that week we held a joint party with Juneteenth.

We had the event with translators, ban cuon, and yellow cake, and you’re like, this potluck is so weird. So then we asked the Vietnamese elders if they knew what Juneteenth was and we asked the black elders if they could explain it, and turns out that a lot of the black elders were Vietnam war vets. I think what was so moving for me was hearing them say, “you know, I was drafted at eighteen to go to Vietnam and when I came back, I didn’t know I had to live next to people that I had hurt, people who look like people I had hurt.” To me that was a pivotal core-memory because this is why I stayed.

VP: What do you feel has been some of the biggest challenges facing VAYLA as it actualizes its grand mission?

JT: I think our grand mission has shifted. Before it was, we’re going to be this intercultural reactive space. By 2060, Asian-Americans are supposed to be the youngest population here in America, and in the south in particular, I am always saying we don’t need ten thousand Vietnamese pharmacists [Chuckles]. Every time I talk to a young person, I’m like, so you’re telling me, at your pretty age of twenty, you want to be behind a CVS counter for the rest of your life? [chuckles] In all seriousness, in the grand scheme in actualizing our mission is incubating the next generation of folks who will take my job.

Like, are we creating a sustainable leadership pathway? How are we thinking about engaging young people in civil rights, social movements, and thinking critically about what freedom and liberation looks like […] Thinking about kids in their twenties, it’s like coming out twice. Like, I majored in English as an undergrad and my mom was like, “you speak English, why?” I’m definitely not my ancestors wildest dreams. They did not dream of this child who is insanely obsessed about finding the right words to tell people about themselves, but I think it’s important to.

The challenge in the south is not just the invisibility of being Asian-American, sometimes it’s the visibility of being Vietnamese-American and the type of erasure we cause […] A lot of what stands in the way of VAYLA in succeeding in its grand mission is the larger infrastructure. I can strategize all I want with my budget each year, but you can’t out strategize the culture of colonialism. So how we approach has to be anti-white supremacist, has to be anti-colonial, the way we incept and think about programming, thinking about how and why we hire, how and why we support, how we honor the people we honor, has to embody the concepts of what we say we are seeking. This mean the way in which we hire, how we pay people—The minimum wage in the state is seven twenty-five, all of our interns are paid at least fifteen dollars. I want it to be sustainable for young people to feel like they can afford to do liberatory work. But to answer your question briefly, it is really the larger infrastructural issues.

VP: You’re a descendent of Chinese-Vietnamese refugees, and a part of the Vietnamese diaspora, how do you feel that affects the way you see the world on a day to day level?

JT: For me, It’s not something I had to contend with until I was put in this position. Is that not insane? I feel like there can be a multitude of intersecting and parallel narratives. I feel like I am as much Vietnamese as I am Chinese, but I feel when people ask me what percent Vietnamese or Chinese, I feel like they are asking me, “how much power did your family have? How resourced was your family? How safe are you? And are you like us? Are you working class? Can I trust you? And I feel like that’s what they’re truly asking me. I feel like what gives folks free pass to not consciously and critically thinking about their freedom is passive aggression, and passive aggression is this continued lack of safety in exploring anything. So the more we name them, as disruptive as they may be, the more powerful we become, and the more we have control over our own perception of self, of the world.

As someone who was a trauma therapist in the past, for me, a level of personal psychology is, what has happened to you, but trauma is also what has not been for you. Liberation psychology asks, “what has happened to you and what continues to happen to you and your people?” And for me being Vietnamese and Chinese is a deep understanding in myself, knowing that my ancestors didn’t only have to leave the Vietnam war, but also the opium war. [big laugh] Tracking my own family history, I understand their movement from southern China along the coast to north Vietnam, to southern Vietnam, so I understand epigenetically what war means to my family. I think it informs the ways in which I had to synthesize and practice what I preach, which is: I believe my community Is the global majority, folks that understand what it means to alchemize a level of ancestral rage.

I does make me different from Vietnamese Catholics here, and I don’t know if it presents a challenge for me to lead. I think it allows me to lead. I had a staff say something about leadership the other day and I think of myself as more pariah, but I think that’s what it takes to incept and think about things differently…

VP: You’ve also recently earned your PhD in social work from USC, congratulations on that, how was that journey on top of all the amazing things you are already doing all of this amazing work?

JT: [big laugh] That was a trauma response as well. During the pandemic, I kept telling young people, I don’t want to die being their executive director [big laugh] I mean it. Like, where do program managers go to die? For me, there was one day at VAYLA where a Tulane professor, who had spent her entire career studying refugees, and she asked me if I had been to Pulao Bidong, which was one of the refugee camps one of my parents were on. And I was so offended, my body was hot, and I asked myself why I was so angry at this lady. Then I realized I was angry because she spent her entire career casually studying my family’s trauma, and you can’t be mad at people if you’re not going to do it yourself.

VP: Right.

JT: I think about this all the time. Like, you don’t need white people for white supremacy. I think people who have survived colonialism knows that. You don’t need bodies in the room to take bodies. My journey at USC was actually very challenging. I had prepared myself for a level of disdain, I would feel, but I didn’t prepare myself to be doing this coursework, seminars, and casual xenophobia during the pandemic, and evacuating—There was like no power in New Orleans for like three weeks. This is what I learned from this program: It’s that it took me my entire academic career, and I don’t know if you relate to this, but you don’t have to try so fucking hard [laugh].

VP: No, of course. You just got to get it done.

JT: Yeah! You don’t have to try so hard. Full transparency, I was a community college kid.

VP: Me too.

JT: I grew up with a single mom and I am twelve years older than my brother. I am the oldest daughter, and like, I remember getting into Stanford and my mom was like, “who is going to watch your brother?” Then she’s like, “I’m not paying for that.” You know, it’s very weird when I tell other people that are non-Asian about that. But with Southeast Asians they understand, like, “yeah duh.” So, I took a year off, I went to Korea for a year, traveled and then I came back. I was doing community college then transferred to Berkley, but I was thinking this entire time, never once, through all of this, not even when I had pneumonia, did I ever ask for an extension [laughs].

VP: That doesn’t exist. That’s not an option.

JT: That’s not a choice. But then when I went to USC, everyone was asking for an extension. And it took me until the last term, where I was like, oh, this is just the culture. This is what it means to be first generation. This is what Western education looks like. Then USC was also immensely wealthy. I mean, I’ve known of rich people, I’ve worked through college and I’ve seen wealth, but you have not seen wealth until you have cohort members who own hospitals [laughs] Like, what? So, long story short, my experience at USC was very eye-opening, because I understood what it meant to arrive at a place where you’re present with yourself and knowing you’re enough. I did not somatically realize how much intellectual work I was constantly doing, often times for people who were not ready to receive it […] My closest friends that I’ve made in this cohort are all first-generation. It’s interesting because, whether they’re from Egypt or Mexico, those were the closest solidarity relationships I was able to build, because those were folks who understood how differently we had to navigate the world.

VP: It’s funny because growing up Vietnamese, my parents’ assumption was always, you’re going to go to college, we don’t know how you’re doing to pay for it, but you’re going.

JT: Do you have an older sister?

VP: I do. Same thing happened with her. She is very similar to you, in fact. For her, if she’s not in the mood for something, she’s gone. She’s very much the person that is going to chase the thing that is happy for her, and I am happy for her. But my parents were very much, no, you don’t have a choice in this(college).

JT: [laughs]

VP: You come from an academic background and you have clinical experience as well, given that this work requires you working with communities facing hardship, which I imagine is emotionally taxing, how have you found the strength to keep working and what are some of your sources of inspiration?

JT: I think I find inspiration when I meet folks like you, to be honest. When I meet folks like you, I feel incredibly less alone. Like there are people who are critically chipping away, and people who are curious about why we are the way we are. No, It’s genuine, I think it is important to feel like you are in a larger community. Often times, New Orleans feels like a town. There are people who do prominent work, and they do it in a way that makes a narrative about Vietnamese Americans, things that are either not relatable or very relatable to young people. I think it was Viet Thanh Nguyen who says, “narrative plenitude is so necessary.”

For me, what keeps me doing this work is often how I feel at home here. The sad part about being in Louisiana is that most of my family is in California. It’s also the easiest part. Because here, I feel like I have so much fertilizer to grow and to incubate a level of radical joy you can only get from constructively suffering. Sometimes freedom and this deep liberation, as a Chinese-Vietnamese person in this body, it’s solace, it’s deep solitude […] The biggest joys I’ve had lately is the young people I work with. They live their lives in a way I wish I could have, at their age. They’re paid, they have health insurance. We have a very diverse AAPI, non-binary team. We have unlimited PTO, and I mean it. I shut the organization down for two weeks because people were so traumatized with George Floyd. I mean, I was working, but to me it is about a level of freedom that is very healing. It’s about making it possible for young people to tell a story that’s different. […] I enjoyed the healing journey that VAYLA has allowed me to be on. It’s kind of like the doctoral journey where you come and you have to work so hard, and then you come to realize, you’ve always been enough—Always been more than enough. Not because you exists in these Identities, but because you believe it […] I also have a passion for mentorship, it is very fulfilling. I am sure people say the same about having kids, I don’t know [laughs].

VP: I don’t know either. It is work at the end of the day, and we can’t romanticize labor.

JT: We can’t. Yeah, Like I’ve been head hunted, a lot. But I feel like even if I was in Indonesia, for example, or anywhere in the world, I would be doing the same diasporic work. I happen to be planted here. I had this conversation with a young person the other day about being a diasporic person, and I made the comparison to weeds. As a diasporic person, wind blows you and you just get planted where you land. And I feel like that is what happened to me in New Orleans, like I am called to give what I know here and grow. Once I grow the cycle will happen again. Hopefully you grow here. Take my job [laughs].

VP: There does seem to be a sense of resilience mostly from people we grow up a round—wanting to belong wherever they end up. So my last question is related to being this figure that stands out, but also wants to belong: Being a woman of color who works in minority spaces to uplift others, what does it mean for you to bringing authenticity into the work place?

JT: We have a lot of openly neuro-divergent staff, which I really appreciate because it takes a level of vulnerability. I think authenticity is a practice, it is not a switch. Like, you can’t switch off and say, “oh, I’m not going to be racist anymore.” It’s kind of like an every day practice. For me, it’s been a lot of healing work to get to this space. Even when people tell me I am unapologetic, I’m like, am I? I think the trauma from being in the diaspora and being so far from home is, often times, is there is a space gap between your healing self and your growth self. Not to get too spiritual, but I really believe in exists in both soul time and real time, and they’re not in sync […] To me, this often just means we need to slow down. Like, when I read all the Asian-American literature, it’s so sad.

VP: There is no room for joy.

JT: Yeah, joy is a practice. Even with contending with being Chinese, I had to do research like, did we commit war crimes? I think knowledge of self is the deepest way we can cultivate authenticity. And that sometimes mean that we have to be comfortable with a level of uncertainty. That’s where infinite possibilities come up. I’ve had a lot of uncertainty in my life, but I am telling you that moving to Chicago was the best thing in my life […] I think it is really important to meet yourself where you’re at. Sometimes we need to be toxic and co-dependent to realized we are enmeshed. And if you’re flagrantly vapid, that’s where you are and that is ok. That’s the radical self-acceptance I think Thich Nhat Hanh had for people, right? Like, you have to meet yourself where you are so you can move on […] I think this practice of letting fear go, little by little, helps.

VP: That was really profound, thank you for your time.

JT: Thank you.

Frustrated Nations: The Evolution of Modern Korea and Vietnam

Lại Nguyên Ân Revives the Portrait of Phan Khôi Once Again

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 22 – Subjects and Sojourners

“First Thắng, Second Chinh, Third Thanh, Fourth Trưởng”: The Four “Incorruptible” Generals of the ARVN

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 21 – Living Abroad

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

National Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES4 years ago

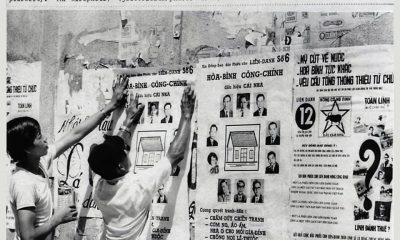

ARCHIVES4 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoChina’s Recent Invention of “Nanhai Zhudao” in the South China Sea (Part 2: Examining the “Nanhai Zhudao” legal basis)

-

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)