Society & Culture

Thinking through Ecological Damage and Forced Displacement with Vietnamese American Literary Studies

Published on

Editor’s Note: This piece has been modified from a conference presentation given by Professor Marguerite Nguyen at New York University in the Spring of 2023. The event was organized by Kevin Li and featured several scholars working on contemporary issues relating to Vietnam and Vietnamese American Studies. It is part of a larger project concerning climate change, Vietnamese American literature, and the ever evolving refugee narratives.

In the past few years, Vietnamese American literature has gained an extraordinary amount of visibility in American culture. Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer(1) and Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous(2) are two examples that reflect this heightened attention, each having received high public and critical praise. Beyond their overall positive reception, these texts have also crossed into the realm of American popular culture. In addition to winning the Pulitzer Prize, Nguyen’s novel has been adapted into a HBO series set to premier in 2024. Meanwhile, Vuong’s novel, as well as his books of poetry, have been widely translated, while his Instagram posts show a range of intellectuals, artists, and celebrities engaging with his works. One could say, and as I have heard at various academic gatherings, that Vietnamese American literature has secured a prominent place on America’s cultural map.

Yet, the cultural and institutional popularity of works produced by artists of color is always precarious. Asian American studies programs and courses, within which Vietnamese American literature is often taught, have been caught in the crossfire of budget cuts, the right’s culture wars and attacks on critical race studies, and a poor understanding of what Asian American studies and its subfields do. In this essay, I comment on my current research project on narratives of Vietnamese refugeehood in New Orleans to highlight how Vietnamese American narratives speak to current concerns about human-induced climate change and forced migration. I’m particularly interested in how portrayals and perceptions of forced migration are largely shaped by how the environment is narratively constructed. The narratives I study illuminate how displaced populations imagine and build communities before, during,and after cataclysmic events and emphasize the relevance of Vietnamese American studies in the contemporary moment.

Conventionally, portrayals of refugees highlight select phases of a forcibly displaced person’s life. These typically include a harrowing journey across dangerous terrain, rescue and resettlement in a new nation-state, and successful adaptation or assimilation, with a few references to memory and cultural heritage thrown in. But this arc in which a refugee environment shifts from one of danger to one of safety—suggesting the shaky borders of the home country and the secure, hospitable borders of the new one—is a naturalized, hegemonic one that erases a refugee’s past and downplays the material conditions that result in environmental instability and, thus, forced migration. Disaster and displacement often happen more than once in a refugee’s lifetime, as does the process of rebuilding community and a sense of home. Thus, what constitutes a refugee’s setting—a refugee ecology—is layered by multiple times and spaces that remain fraught rather than resolved.

In Louisiana, a dense population of Vietnamese Americans resides in New Orleans East, which lies on the easternmost edge of New Orleans and is not typically associated with more iconic areas of the city, such as the French Quarter and Garden District. Yet this area houses over 20% of Greater New Orleans’ population and over 60% of its land mass. Portraits of Vietnamese refugee environments in and around New Orleans have often centered on two images: Vietnamese diasporic farms, which refugees began cultivating by their apartments as soon as they began arriving in 1975, and the local Vietnamese Catholic church, Mary Queen of Vietnam (MQVN), which serves as a spiritual and community anchor for the primarily Catholic community. Vietnamese Americans here have found themselves at the center of fluctuating perspectives about who they are and what their roles are in narratives of the city, particularly as distinguished by pre- and post-Katrina contexts.

In Louisiana, a dense population of Vietnamese Americans resides in New Orleans East, which lies on the easternmost edge of New Orleans and is not typically associated with more iconic areas of the city, such as the French Quarter and Garden District. Yet this area houses over 20% of Greater New Orleans’ population and over 60% of its land mass. Portraits of Vietnamese refugee environments in and around New Orleans have often centered on two images: Vietnamese diasporic farms, which refugees began cultivating by their apartments as soon as they began arriving in 1975, and the local Vietnamese Catholic church, Mary Queen of Vietnam (MQVN), which serves as a spiritual and community anchor for the primarily Catholic community. Vietnamese Americans here have found themselves at the center of fluctuating perspectives about who they are and what their roles are in narratives of the city, particularly as distinguished by pre- and post-Katrina contexts.

Prior to Hurricane Katrina, much media and scholarship enlisted images of Vietnamese diasporic farms and MQVN in ways that framed the community as an outsider population with traditional Asian ways whose future integration in New Orleans would depend on their ability to assimilate and detach from the past(3). For example, MQVN became a space where one could glimpse parishioners walking to church, with many dressed in the traditional aó dai, or where New Orleanians could immerse in the colorful visuals and flavorful dishes of MQVN’s popular annual Tet Festival. What identified Vietnamese diasporic farming were images of older refugees in conical hats and traditional clothes using Vietnamese tools, working long hours in southern heat and humidity to care for exotic crops and make them available to the wider public at Saturday morning markets.

Locals and scholars predicted that, as the community assimilated, the farms might disappear, and the church might lose its density. As one observer noted, “The acculturation process may ultimately lead to the disappearance of the market gardens,” while other commented, “in 20 years we’ll be into a second generation, they will all speak English, there will be a lot more social mobility and they’ll lose their refugee status. . . . All will be forgiven if they throw beads and cook good food.”(4) Although somewhat integrated into the city’s, cultural, spiritual, and economic environment, they were still seen as peripheral—geographically separated and politically quiet, not full historical and political subjects as long as they remained tied to their pasts.

The prevailing story of Vietnamese foreignness gradually assimilating changed dramatically after Hurricane Katrina, when the Vietnamese American population gained increased attention due to their rapid rate of return and rebuilding. For instance, MQVN became a shared space of worship for Vietnamese Americans and Blacks when it relaunched mass after the storm(5). If the farm had been predicted to disappear pre-Katrina, post-Katrina it became a representation of the community’s commitment to the land and city, even foregrounded as a possible model for a more sustainable future. This was, perhaps, most evident in the award-winning Viet Village Urban Farm design, a 28-acre plan based in the New Orleans East community and inspired by Vietnamese agricultural practices. No longer simply a foreign presence living on the city’s outskirts, Vietnamese Americans became an emblem of resilience, their rehabilitation of New Orleanian spirit, homes, and land displaying virtuous citizenship and hope for New Orleans’ future.

What is worth noting here is that aspects of Vietnamese spiritual and agricultural life are habitually extracted and decontextualized in conventional representations. Narratives that emphasize Vietnamese refugee contributions can enact a neoliberal story of self-sufficiency and resilience rooted in essentialist, static ideas of Vietnamese culture. As Eric Tang has shown, such a reading relies on model minority stereotypes and erases the dispossession, struggle, and displacement of Black communities. Across pre- and post-Katrina, Vietnamese food and faith have been more or less cast in apolitical and dehistoricized pastoral terms, constructing a notion of refugeehood oriented around virtuous cultivation of land and character.

In The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, Amitav Ghosh asserts that colonialism and its intellectual counterpart, Enlightenment thinking, profoundly disrupted economies and geographies and changed the earth’s atmosphere while glorifying humans over nature. Ghosh positions the novel as the literary manifestation of this development, inscribing storyworlds that have a limited approach to portraying time and space and are woefully unable to establish broader linkages beyond the national frame. As a “self-contained ecosystem,”(6) novels make “each setting . . . particular to itself” such that “connections to the world beyond are inevitably made to recede.”(7) I would add that these elisions have also extended across genres beyond the novel.

In this light, Vietnamese American narratives push against the spatio-temporal restrictions that the Euro-American novel has canonized, taking on a much more capacious and multidimensional character. From the critical perspective of deep postcolonial history and critical race studies, Vietnamese refugee Catholicism and farming are not simply quaint cultural phenomena that represent smooth importations of static Vietnamese heritage or simply refresh Louisianan landscapes, cuisine, and socio-economic life. Such practices constantly evolve in relation to major and minor changes. For instance, Vietnamese American farming in eastern New Orleans has shifted depending on environmental and political exigencies, ranging from soil-based farming to aquaponics experiments when soil is contaminated due to hurricanes or oil-related damage.

The dynamic, ongoing nature of Vietnamese refugee adaptation points to the fact that socio-ecological crises that Vietnamese Americans face, which link to those that neighboring Black and Brown communities face, are recurring. They encompass not only Hurricane Katrina but also the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, numerous toxic landfills in New Orleans East, and large-scale industrial projects that are often planned in or near communities of color in New Orleans East. For example, the original Bring New Orleans Back plan had literally cut off Versailles from the post-Katrina map, designating it as green space unfit for rebuilding post-storm. City officials also decided to use land in New Orleans East as a dumpsite for Katrina waste, further increasing the social, political, and physical vulnerability of the area’s marginalized populations. It took more vigilant political representation, legal action, and activism before a new plan that included previously-neglected parts of New Orleans East emerged. Even then, the area remains underserved in terms of food and health justice, while southeastern Louisiana more broadly has some of the most vulnerable coastline in the world.

Vietnamese refugee experiences with disaster and displacement are not only recurring but also transnational, involving multiple wars in Southeast Asia in addition to the Vietnam War. The long social, political, and military history of Vietnam tends to remain absent in U.S. accounts. Take, for instance, the words of an interview subject from the documentary A Village Called Versailles, Ngo Ly, who identifies the church and farm-derived market as two things that have helped build community in Louisiana: “This town is not like the most populated Vietnamese refugee town. But this neighborhood is the most concentrated, this neighborhood is the most dense. Not other places can be like this. We . . . [go] to the market, to church, we meet each other. . . . we live together, we understand each other, identify with each other, so I see that and am happy.” Ly depicts a diasporic intimacy based in the physical space of New Orleans, but it also seems to stretch across time and space. This strong sense of mutual understanding is informed by a shared present and past that links Katrina-related displacement to a long history of forced migration: “I’ve fled three times, this is the third time. ’54 in Vietnam, to South Vietnam, . . . After I went South . . . then I came here. This hurricane is different, . . . I still had hope as I fled, hope to return.”(8)

The recurring, transnational quality of Ly’s narration anchors contemporary forced displacement in colonial and postcolonial history that helps to draw out the nuances of Ly’s comments. Ly specifies that he is from Nam Dinh, northern Vietnam, and migrated to Phuoc Tinh, southern Vietnam after the division of Vietnam in 1954 following the Geneva Accords. He was eventually elected as leader of the village but, nevertheless, took guidance from the pastor of his church when deciding whether or not to flee in 1975 as the fall of Saigon approached. He states, “I would have left, but our pastor and those close to me wouldn’t go, so I also stayed behind.” This led to him being imprisoned in a reeducation camp because he had been in the South Vietnamese military. During his time in camp, his wife was shot and killed by communists, leaving his remaining children alone to fend for themselves until he was released. Ly reveals the central role of the Catholic church in watershed moments of his biography(9).

Ly’s experiences in North and South Vietnam across multiple periods of social, political, and environmental crises compel consideration of how practices of faith and food might be traced back to his “original” home of Nam Dinh and how empire and postcolonialism in Southeast Asia have continued to shape the diasporic environment. Like Ly, a large number of Vietnamese Americans in New Orleans East come from northern Vietnamese provinces such as Nam Dinh as well as Ninh Binh. These areas have long been vulnerable to political and environmental crises. In the pre-French state, a system of aid developed that was based on tax relief, mutual assistance, communal farming systems, and granaries to supply rice and regulate prices during times of flood and famine. The granary system was dismantled under the French, and colonial officials often attributed famine to natural disaster instead of state action and failed relief(10). During World War II under Japanese occupation, northern and central Vietnam experienced a traumatic famine resulting in one to two million deaths, largely caused by Japanese control of rice production that directed rice to Japan and its empire while Vietnamese suffered malnutrition and starvation(11).

During the First Indochina War (1946–54), certain villages in the northern Vietnamese provinces of Nam Dinh and Ninh Binh, namely Bui Chu and Phat Diem, constituted a Catholic autonomous zone—“the only areas in central and northern Vietnam not under drv [Viet Minh–led Democratic Republic of Vietnam] or French control,” as Charles Keith notes. Catholic leaders here experimented with various programs such as cooperatives and unions in the effort to create a separate social, political, economic, and military state(12).

When Vietnam was divided at the seventeenth parallel after France’s defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, Catholic leaders played a large role in organizing southward migrations of thousands of Catholics and Buddhists to the newly-established Republic of Vietnam (RVN, or South Vietnam). Once again, structures for land development and communal living were implemented to establish military, social, and political autonomy, evoking the Catholic autonomous zones from the North(13). The hope was for populations to become a self-sufficient community functioning in solidarity. Self-sufficiency here was defined differently than in the American exceptionalist vein. It meant a rejection of “capitalist imperialism” and any U.S. designs to make South Vietnam its protectorate.

Carrying their psychic and bodily experiences across French, Japanese, and U.S. imperial regimes with them (and the various backers involved, such as China and the Soviet Union), histories of drought, flood, famine, mass death, and mass rebuilding—as well as hope for creating a new future—have been passed on from generation to generation among refugees who migrated from North Vietnam to South Vietnam and from South Vietnam to the U.S. All of these threads comprise Vietnamese refugee ecologies that make up southeastern Louisiana as, eventually, a large number of those originally from northern Catholic villages ended up in Louisiana, like Ly.

To return to Ly’s comments, the structure of narrating refugee ecology, hence, is not linear and teleological. It is recursive, winding around different instances of forced displacement and community-building. The recursivity of displacement shows how Ly’s memory records a history of recurring, transnational movement, with references to the church and farms asserting an environment of mutual identification and embedded with a history of worldbuilding. Ly’s expansive spatio-temporal narration diffuses a U.S.-centrism that, as Mimi Thi Nguyen and Yen Le Espiritu have shown, expects the refugee’s gratitude and assimilation in return for “rescue.”(14)

However, refugee ecology is not inherently positive or progressive. To account for the complexity of refugeehood, my project also analyzes how the selective dispensation of official refugee status by national and international forces also replicates settler colonial agendas and reinforces racial hierarchies. Rescuable refugees are those who can showcase humanitarian concern, but, as Kelly Oliver argues, refugee rescue is also a form of “carceral humanitarianism” that prioritizes aid for certain forcibly displaced people while keeping others in suspended states of deprivation(15).

Thus, while the U.S. has long been defined as a site of refuge, ecocritical literary analysis with an eye toward race, colonial history, and regional details traces how refuge is differently imagined and practiced. In this picture, Vietnamese American narratives and literary studies have much to contribute to discussions that are concerned with the historical and political causes, consequences, and potential forms of agency in light of contemporary ecological damage.

References:

- Viet Thanh Nguyen, The Sympathizer (New York: Grove Press, 2015).

- Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (New York: Penguin, 2019).

- Marguerite Nguyen, “Vietnamese American New Orleans.” Minnesota Review 84 (2015): 118. Although in the public imagination the Vietnamese Catholic church has become synonymous with the Vietnamese American community, it is important to note the significant Buddhist and West Bank populations that often get eclipsed by the attention given to Catholic Vietnamese Americans in the city. See Allison Truitt, “The Viet Village Urban Farm and the Politics of Neighborhood Viability in Post-Katrina New Orleans,” City & Society, 24.3 (2012): 321-338.

- Marguerite Nguyen, “Refugee Pastoralism,” in Remaking New Orleans: Beyond Exceptionalism and Authenticity, ed. Thomas J. Adams and Matt Sakakeeny (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019) 222.

- S. Leo Chiang, A Village Called Versailles (Harriman, New York: New Day Films, 2009).

- Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016) 61.

- Ghosh, 59.

- Chiang.

- Chiang. Some of these comments are from unpublished translations of Ngo Ly’s interview.

- Van Nguyen-Marshall, “The Moral Economy of Colonialism: Subsistence and Famine-Relief in French Indo-China, 1906-1917. International History Review 27.2 (2005): 239–44.

- Van Nguyen-Marshall, Review of Rice Wars in Colonial Vietnam: The Great Famine and the Viet Minh Road to Power.” Pacific Affairs, 89.3 (2016): 714-715.

- Charles Keith, Catholic Vietnam: A Church from Empire to Nation (Oakland: University of California Press, 2012) 223.

- Edward Miller, Misalliance: Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and the Fate of South Vietnam (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013) 229-235.

- Mimi Thi Nguyen, The Gift of Freedom: War, Debt, and Other Refugee Passages (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012). Yen Le Espiritu, “Toward a Critical Refugee Study: The Vietnamese Refugee Subject in US Scholarship.” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 1.1-2 (2006): 410-433.

- Kelly Oliver, Carceral Humanitarianism: Logics of Refugee Detention (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

Frustrated Nations: The Evolution of Modern Korea and Vietnam

Lại Nguyên Ân Revives the Portrait of Phan Khôi Once Again

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 22 – Subjects and Sojourners

“First Thắng, Second Chinh, Third Thanh, Fourth Trưởng”: The Four “Incorruptible” Generals of the ARVN

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 21 – Living Abroad

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

National Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES4 years ago

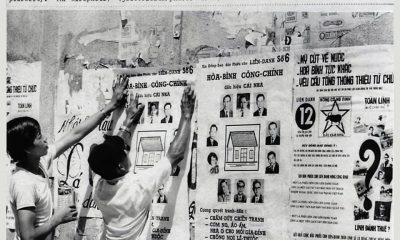

ARCHIVES4 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoChina’s Recent Invention of “Nanhai Zhudao” in the South China Sea (Part 2: Examining the “Nanhai Zhudao” legal basis)

-

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)