ARCHIVES

SERIES C: STRUGGLE FOR CENTRAL VIETNAM, JANUARY-MAY 1955

Published on

By

Nu-Anh Tran

SERIES C: STRUGGLE FOR CENTRAL VIETNAM,

JANUARY-MAY 1955

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction to Series C

THE SECESSION OF THE ĐẠI VIỆT PARTY IN QUẢNG TRỊ

C1. Despatch 10 from the US Consulate in Huế to the Department of State, November 12, 1957 / Robert Barbour

C2. Bức thư tâm huyết số 6, ngày 5 tháng 3 năm 1955

THE SECESSION OF THE VIETNAMESE NATIONALIST PARTY IN QUẢNG NAM AND QUẢNG NGÃI

C3. Despatch 351, US Embassy in Saigon to the Department of State, April 27, 1955 / Randolph Kidder and John Donnell

C4. Despatch 11, US Embassy Saigon to the Department of State, July 8, 1955 / Frederick Reinhardt

C5. Bức thư không niêm của Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng gửi Ngô Đình Diệm ngày 9 tháng 5 năm 1955 / Trung Ương Đảng Bộ Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng

INTRODUCTION TO SERIES C

The State of Vietnam (SVN) faced a unique challenge in the central region after the Geneva Agreement of 1954. Almost all of Vietnam’s midsection had been the territory of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) during the First Indochina War (1946-1954), with the French and SVN only controlling a narrow strip of the coast around Huế, major cities, and some provincial capitals. The ceasefire agreement abruptly redrew the boundaries between the two regimes and placed the southern half of central Vietnam within the regroupment zone of the SVN. As the communist forces withdrew northward and the French transferred military authority to the SVN, the Saigon-based government struggled to fill the administrative and military vacuum left behind.

The difficulty of the task forced Ngô Đình Diệm’s political faction to cooperate with other anticommunists. The Diemist faction in central Vietnam consisted mainly of the premier’s semi-clandestine Cần Lao party, led by his younger brother Ngô Đình Cẩn. Cẩn was based in the greater Huế area, and the Cần Lao had emerged as a regional locus of anticommunist nationalism in the early 1950s. Many of Cẩn’s followers were Catholics who had fled to Huế from DRV-controlled areas. Diệm’s appointment gave the Cần Lao a distinct edge over all potential competitors among the anticommunists, and the premier allowed his brother to secretly control the regional government and act as the unofficial ruler of central Vietnam.

Cẩn placed Cần Lao partisans in the highest levels of the administration but did not have enough partisans to staff the lower ranks, and he was forced to rely on the regional branches of the Đại Việt Nationalist Party (Đại Việt Quốc Dân Đảng) and Vietnamese Nationalist Party (Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng, VNP). During the war, both parties had maintained skeleton organizations in central Vietnam despite persecution by the communists. They had also filled the lower ranks of the SVN’s administration and the officer corps of the regime’s provincial militias. The Đại Việt was strong in Quảng Trị and Phú Yên, and the VNP had a presence in the four contiguous provinces of Quảng Ngãi, Quảng Nam, Bình Định, and Kontum. Cẩn’s wing of the Cần Lao and the other parties had collaborated as members of the Movement for Unity and Peace (Phong Trào Đại Đoàn Kết và Hòa Bình) in 1953, and Cẩn maintained the three-way alliance during the early months of Diệm’s tenure. The younger Ngô brother allowed many partisans of the Đại Việt and VNP to remain in their administrative positions and encouraged them to reoccupy former communist territory. But Cẩn and his followers did not trust their allies and wanted to exert greater control over the entire region. The alliance abruptly fractured in the spring of 1955 when the Đại Việt and VNP seceded from the SVN and formed short-lived resistance zones, the former party in Quảng Trị and Phú Yên and the latter in Quảng Nam and Quảng Ngãi. The national army later crushed the rebellions, and the government arrested members of both parties, including partisans unconnected to the rebellions. The violence and mass arrests amounted to a political purge and permanently ruptured the alliance between the Diemist faction and their erstwhile allies. Afterwards, Cẩn consolidated power by filling the lower echelons of the administration with new Cần Lao partisans.

Note that the documents in this series often refer to the DRV as the Việt Minh or the Việt Cộng. The latter epithet was also used to refer to Vietnamese communists more generally. Individuals whose names are only partially provided have been more fully identified in brackets, when possible. When the identity could not be confirmed, a question mark appears in brackets. Orthographical and other errors in the documents are indicated by the word sic placed in brackets.

THE SECESSION OF THE ĐẠI VIỆT PARTY IN QUẢNG TRỊ

The Đại Việt party was divided into three distinct regional branches by 1954. Nguyễn Tôn Hoàn’s southern branch and Hà Thúc Ký’s central branch coordinated their actions with each other but not the party’s northern émigré branch. In the south, Hoàn broke with Diệm in fall 1954 during the tense negotiations over the composition of the cabinet. The frustrated Hoàn went abroad and unsuccessfully lobbied France and the US to pressure Diệm into broadening his government. A few months later, relations deteriorated between the Đại Việt and the central regional government in Quảng Trị province. The province chief Trần Điền was the brother-in-law of Hà Thúc Ký, and several officers in the provincial militia and local units of the Vietnamese National Army were party members. The central regional government unexpectedly canceled a military operation by the militia, and alarmed Đại Việt officers led their men into the foothills and declared a resistance zone in Ba Lòng valley on February 11, 1955. The national army retook Ba Lòng a month later. In 1957, the Military Court in Huế convicted over forty partisans related to the incident in Quảng Trị.

Robert Barbour, the American consul in Huế, provided an overview of the secession and the subsequent trial of the partisans in his report to the State Department. Barbour was not present in Quảng Trị during the secession, and he stitched together newspaper accounts of the incident. Therefore, his missive reflected the version of events that Diệm’s government permitted the Vietnamese media to publish. Note that Barbour referred to the provincial militia as the “provincial police force.”

C1. Despatch 10 from the US Consulate in Huế to the Department of State, November 12, 1957

Robert Barbour

Subject: Dai Viet trial at Hue

Summary

In a recently-concluded two-day military trial at Hue, forty-six former leaders and sympathizers of the Central Vietnam Dai Viet movement were tried – mostly in absentia – for plotting against and opposing the national authority, charges which grew out of the defection of Dai Viet members of the armed forces in Quang Tri Province in February 1955 and their subsequent armed opposition to military operations sent to compel their submission. The most prominent individual on trial was the former chief of the province, who is generally believed to have been a naïve Dai Viet tool. Despite lurid allegations to the contrary, the trial failed to show convincingly that the movement and the insurrection received overt French support. In general the trial seems to have been a formality to sentence individuals who, with three exceptions, had already been judged guilty.

Source Note

Most of the material in this report was taken from newspaper accounts of the trial and their description of events leading to it. Fortunately, it has been possible to clarify this relatively unknown sequence of events and place them in their proper perspective through conversations with Vietnamese officials in the Hue area, particularly the assistant chief of Quang Tri province, who also served in that capacity during the period the events described took place.

Like the Binh Xuyen leaders recently brought to trial at Saigon, the once important Central Vietnam Dai Viets have also felt the impact of the Vietnamese Government’s campaign to square accounts with former troublemakers. On October 24 and 25[,] forty-six former Dai Viet leaders, most of whom were still at liberty, were tried by a military court at Hue for “plotting against the national authority and transgressing against the security of the State.” Of this number two were condemned to death in absentia, two were sentenced in absentia to forced labor for life – all four had their properties confiscated – thirty-nine received sentences varying from five to fifteen years of forced labor, and three were acquitted.

To understand just exactly what the so-called “Dai Viet Insurrection” consisted of and how it came about is difficult, to say the least, and to do so requires a laborious sifting of claims and counterclaims, charges and countercharges. Undoubtedly the greatest impetuses to the Dai Viet’s failure to support the then-sickly national government were the political vacuum which existed in Central Vietnam in the days following the Geneva Agreement and the belief that they would be called to replace the Diem administration. In this connection it is worthwhile to recall that the regroupment and evacuation of the communist troops in South Vietnam took place over a period of three hundred days and was not concluded until May 1955. Thus it was that when Quang Tri province was cut in two by the Geneva Agreement’s provisional demarcation line, the brand new national authority on the southern side probably floundered around for a bit and sought to muster every available anticommunist force to fill the vacuum.

Among the forces available in Quang Tri at that time were the embryonic Vietnamese National Army and the provincial police force, and neither of them were stalwarts of the regime. The third force—and, during the months immediately following the Geneva Agreement, the only effective military units in the area—were the soon to be withdrawn French Union troops. Although these organizations shared a common anticommunist outlook, the first two contained a substantial number of Dai Viet supporters who were not unquestioning in their loyalty. However, it is not unlikely that their presence was known and accepted and their anticommunist support welcomed by the local authorities.

Unfortunately, like the sects in the south, the Dai Viets suffered delusions of grandeur. Late in 1954 and early in 1955, as the fortunes of the Diem government seemed to decline, the troubles besetting it to increase, and the threats to its existence to become more ominous, the Dai Viet members of the army and police forces in Quang Tri province increased their anti-government activities and ultimately succeeded in subverting a large segment of the police force and almost an entire army battalion, the 610th. One of the most effective arguments said to have been used by the Dai Viet proselytizers was the rumor that the senior Dai Viet leader, Nguyen Ton Hoan, had seen President Eisenhower and received from him a letter pledging his support to the Dai Viet efforts to gain power in Vietnam.

When word of the deteriorating situation in Quang Tri reached the ears of the Central Vietnam administration at Hue early in February of 1955, the 610th battalion was ordered withdrawn to Hue. However, rather than accept the resultant loss of power which such a move would have entailed, the Dai Viet leadership decided to defect. An estimated 635 men from the 610th battalion, including the battalion commander and other officers, 160 members of the provincial police force, and various other civil and military officials left their posts and made for the Dai Viet headquarters in Ba Long district, Quang Tri province. Here for about two weeks they drilled and trained, organized alleged assassination and terrorization committees, and prepared for greater things.

During the two-week period following the Dai Viet defection, a number of appeals to rejoin the fold were made by the government. All failed. At least one emissary was sent in to attempt to change their minds, but he narrowly escaped execution. Airplanes dropping surrender leaflets were fired upon. Finally, on February 26 a military operation lasting until March 15 was set against Ba Long and was not withstood. Various Dai Viets were killed, others taken prisoner in battle or in the weeks following, and still others escaped to Laos and Cambodia or rejoined other Dai Viet bands elsewhere in Central Vietnam.

The most prominent of those arrested at the time of the revolt was Tran Dien, a former journalist, writer, political scientist, director of the Central Vietnam Information Service, and chief of Quang Tri Province at the time of its Dai Viet troubles. It was Dien’s misfortune to have as his brother-in-law Ha Thuc Ky, a militant Dai Viet intriguer. Undoubtedly aware of the Dai Viet presence in the provincial security forces but apparently eager to use them to combat Viet Minh political activities, Dien was probably persuaded by his brother-in-law to wink at the political activities of the subverted units and to assist them to obtain arms. It is this assistance which was charged against him during the trial as “a diversion of public funds” to rebellious forces.

Although some Vietnamese newspapers described Dien as “the promoter” of the whole affair, it is more likely that he was a sympathetic dupe. This view is held by a number of Vietnamese government officials in the Hue including Nguyen Huu Thu, the present assistant chief of Quang Tri province, who held the same position under Dien. These officials concede privately that Dien may have been sympathetic to the Dai Viet movement, but in using all the forces at his command to combat communist activities at a crucial vacuous period, he probably believed he was acting in food faith with the national government. Although Dien maintained his innocence throughout the trial, he was sentence to five years of forced labor – a relatively light penalty. Recent clandestine radio broadcasts (presumably from Cambodia) have tried to confer on Dien the “honor” of having directed all Dai Viet activities in Quang Tri, but these broadcasts may have been inspired by a desire to put all the responsibility for the insurrection on his shoulders.

One of the most popular and most frequent allegations during the trial at Hue was that of French assistance to the Dai Viet forces. Various French officers named Blanchy, Climbal, Franquis, Lavalou, and Passage were said to have supplied arms and ammunition to them and to have transported these items to the Dai Viet centers. This is probably a half-truth. The period of Dai Viet activities in Quang Tri was a time when the French forces were beginning their withdrawal from Vietnam and turning over quantities of military equipment to Vietnamese national units. In these circumstances it may be assumed that the Dai Viet subverted units in the army and police force [that] would receive French arms. While some individual French officers may have been pleased to see these items in Diet Viet hands, it is more likely that the transfer of arms and equipment was seen as a routine execution of a bona fide agreement with the Vietnamese government. This belief is borne out by a statement read during the trial quoting a French officer to refusing to hand over arms and ammunition to Dai Viet groups but expressing a willingness to comply with any official request from the legal authorities of the national government.

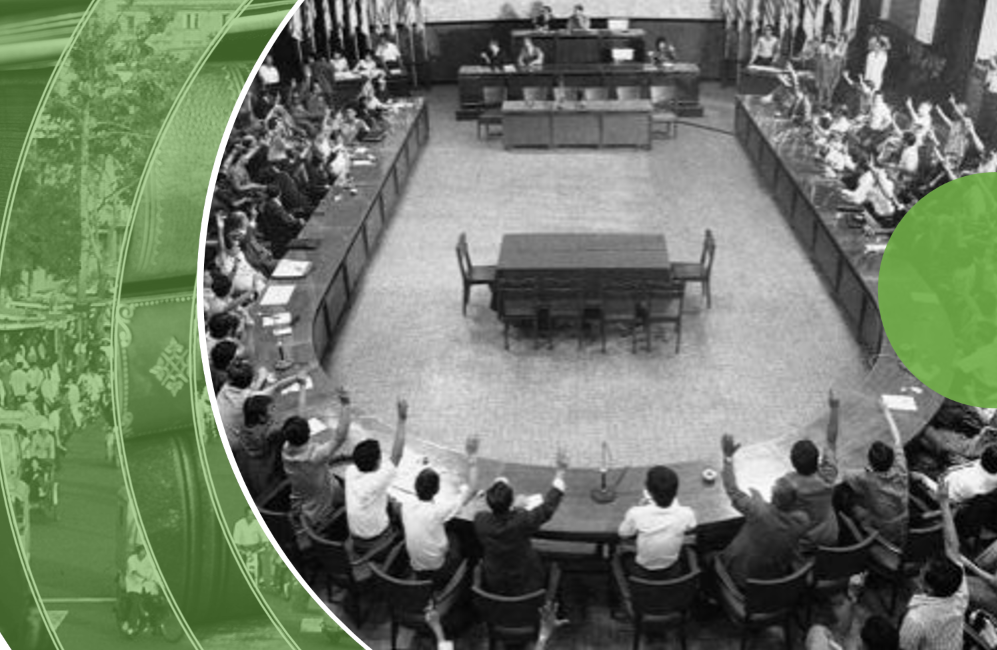

Perhaps the large crowds which flocked to the two days’ trial were disappointed that the disclosures were not more frequent and more lurid than those to which they were treated. In any case, it is evident that considerable local attention was centered on the examination, for each morning saw large crowds of people attempting to gain entrance to the Hue Court of Appeals building, where the military trial was held. Perhaps one reason for this interest was because the trial was the first open political hearing to take place in Central Vietnam since the country gained its independence. Another obvious reason is because the events resulting in the trial took place so close to home, and it is likely that many members of the families of those on trial were among the spectators.

It has been explained that because of the nature of the crime (against the security of the state) and because a large number of the prisoners had been members of the armed forces, a court martial was prescribed. Accordingly, the court consisted of a civilian president, a magistrate, and four military judges. The prosecuting attorney was also an army officer. For the defense there were three civilian lawyers from Tourane [Đà Nẵng]. Of the forty-six individuals actually on trial, only seventeen were actually at the bar. Four are said to be fugitives in Vietnam and twenty-five are believed to have escaped abroad.

In many respects the trial at Hue seemed not to be concerned with determining whether the individuals were guilty, but how guilty. At one point one of the judges asked the leading defendant, Tran Dien, how he could have done such things as those of which he was accused. At another, Dien, who stoutly protested his innocence throughout, heard his lawyer explain that what he had done was not to engage in rebellion but rather to create “internal disturbances,” a statement which brought Dien to his feet protesting that if his lawyer did not stop talking that way he, Dien, would be in even more trouble than he already was.

However, since all those present were claimed to have confessed their crimes during the sessions with the examining magistrate, it may be assumed that the short open trial was seen as a mere formality to pass sentence. It was a bit of window dressing to show that legal processes are observed and at the same time to convince the population of the folly of attempting [to] forcibly to resist the government.

Robert E. Barbour

American Consul

Source: Despatch 10, Huế to Department of State, November 12, 1957, National Archives and Research Administration (NARA), College Park, Maryland, Record Group 59 (RG59), Central Decimal Files (CDF) 1955–1959, 751G.00/11-1257.

* * *

A leaflet produced by the Đại Việt party in central Vietnam provides a contrasting perspective of the secession in Quảng Trị. The document linked the events in Quảng Trị with the sect crisis in southern Vietnam and also commented on other contemporary issues. Although the leaflet offered some accurate details about the secession, it made incorrect claims about Nguyễn Tôn Hoàn’s success abroad, the sect crisis, and Diệm’s position on the Geneva Agreement. The document features some unusual words, unconventional orthography, and small errors, and the bracketed text provides clarification, when possible.

C2. Bức thư tâm huyết số 6, ngày 5 tháng 3 năm 1955

Đề phòng nghiêm mật

Ít bữa nay, những ai từ Saigon đi Lục Tỉnh, hay từ Lục Tỉnh đi Saigon, đều nhận thấy quanh châu thành Saigon, quân đội khám xét rất nghiêm ngặt. Cho tới những sỹ quan cũng bị khám xét cẩn thận, có công lệnh mới được đi thoát hàng rào, và khẩu súng có giấy đàng hoàng, đúng số mới khỏi bị tịch thâu giữ lại. Các xe của Cao Đài, Hoà Hảo bị xét nghiêm ngặt hơn nữa. Nhiều người bị rôn [sic] trở lui…

Mọi người đều ngơ ngác xầm xì: “Có loạn lớn tại Hậu Giang. Chắc rằng Cao Đài, Hoà Hảo đánh lẫn nhau, hoặc là Quân Đội Quốc Gia đương hành quân lớn đánh quân đội của Ba Cụt, nên mới cần phòng ngừa như vậy.”

Thật ra, Hậu Giang đã yên tỉnh

Ngày Thiếu Tướng Trình Minh Thế đem một ít quân về diễn binh tại Saigon, cũng là ngày mà một thể liên minh khác thành lập, trái với điều mà Thủ Tướng Diệm dự tính.

Lấy tiền của viện trợ Mỹ giúp di cư, Thủ Tướng Diệm cố mua chuộc nhóm này, nhóm nọ và cố lợi dụng họ gây ra cuộc nội loạn tôn giáo. Trong chương trình của ông Diệm, Cao Đài, Hoà Hảo phải đánh lẫn nhau, và phe nào thắng sẽ bị tiêu diệt nốt về sau. Các nhóm đều biết như vậy.

Vì thế, hôm Trình Minh Thế về thành, đã có một cuộc hội họp giữa Cao Đài và Bình Xuyên. Dự họp, có Tướng Trình Minh Thế, Tướng Nguyễn Thành Phương, Tướng Bảy Viễn, ông Phạm Công Tắc. Kết quả cuộc họp: hai nhóm quyết định không để cho ông Diệm lợi dụng.

Mấy bữa sau, trong khi Cao Đài công kích tướng Ba Cụt, và các trận đánh giữa Cao Đài và Hoà Hảo bắt đầu xảy ra, thì Tướng Trình Minh Thế, Tướng Nguyễn Thành Phương, xuống tới Cái Vồn gặp Tướng Lê Quang Vinh (tức Ba Cụt) để cùng ký hoãn chiến và đoàn kết, không để ai lợi dụng. Có Tướng Năm Lửa và Tướng Bảy Viễn chứng kiến…

Liền đấy, Hậu Giang êm tiếng súng.

Nhưng lại sợ một cuộc đánh nhau khác

Hậu Giang im tiếng súng, nhưng đến lượt ông Diệm yêu cầu quân đội chặn hết thảy các ngã đường từ Lục Tỉnh lên Saigon để phòng ngừa bất trắc.

Mượn tay Cao Đài đánh Hoà Hảo là vì đa số Quân Đội Quốc Gia không muốn gây lại cảnh cốt nhục tương tàn nhất là họ cũng hiểu đánh xong rồi cũng sẽ bị sa thải để ông Diệm đem người của Đảng Cần Lao Nhân Vị của ông Nhu thay vào. Nay thấy các nhóm Quân Đội Cao Đài, Hoà Hảo hợp lại với nhau, ông Diệm gặp thất bại lớn, phải phòng ngừa mấy nhóm đó chống lại mình.

Việc tiến triển

Lập trường của mấy nhóm tôn giáo đối với chính phủ Ngô Đình Diệm rất giản dị: họ muốn dân chủ, tự do tín ngưỡng chống lại chính sách độc tôn của chính phủ. Ông Diệm xúi dục nhóm này đánh nhóm nọ, là chính sách gây nội chiến tôn giáo, là chia rẽ hàng ngũ quốc gia. Trong lúc này là lúc hợp sức chống cộng sản, gây chiến tranh tôn giáo có lợi gì không? Chiến tranh tôn giáo ấy sẽ có lợi cho quốc gia hay lợi cho cộng sản và cho ngoại quốc? Chiến tranh ấy có đi đến thống nhứt quốc gia không, hay sẽ kéo dài bất tận? Đấy, dù ở nhóm quốc gia nào cũng vậy, phải đặt vấn đề như thế.

Bởi tình trạng ấy, cho nên các nhóm quốc gia tôn giáo mới tính chuyện quốc gia hoá quân đội tự trị, nhưng chỉ với một chính phủ nào thật sự yêu nước và liên kết được các đảng phái trong cuộc tranh đấu chung chống cộng sản đặt dưới sự điều khiển của những người có kháng chiến chống thực dân và chống cộng sản chứ không phải chỉ là “chí sĩ” trong những lúc toàn dân kháng chiến hay xuất ngoại trong những buổi nhà nước ngửa nghiêng” [reference to Ngô Đình Diệm].

Bây giờ là lúc chống cộng, tranh đấu giành độc lập. Vào lúc không có cộng, không có quốc tế, gây chiến tranh nội bộ còn không được thay, huống chi lúc này có cộng sản sẵn sàng diệt tan cả quốc gia. Gây nội chiến mà biết rằng không thể đủ sức chấm dứt được trước khi cộng sản tràn xuống miền Nam, là một cái nguy rất lớn.

Nhiệm vụ giờ đây không còn ở tay một chính phủ nhu nhược yếu hèn, mà muốn làm tàng? Nhiệm vụ ở các khối quốc gia có thực lực, phải mau chấm dứt các xích mích, xây đoàn kết chặt chẽ, tự mình bỏ tình trạng quân đội tự trị để xây đắp quốc gia chung. Bước đầu trước hết là chấm dứt xích mích.

Cũng vì thế mà mấy việc kể trên đã tiến triển hơn: giữa các khối Cao Đài, Hoà Hảo, Bình Xuyên đã chung ký kết một thứ minh ước, thề hợp sức với nhau và không bao giờ xích mích cùng nhau. Những người ký: các ông Phạm Công Tắc, Trình Minh Thế, Nguyễn Thành Phương, Trần Văn Soái (Năm Lửa), Lê Quang Vinh (Ba Cụt), Nguyễn Văn Viễn (Bảy Viễn), Lâm Thành Nguyên.

Cái lỗi lầm lớn nhất trong đời ông Diệm

Trong lúc ấy, ông Diệm lại phạm vào một lỗi lầm lớn nhất trong đời chính trị của ông. Ông mượn tay binh đội quốc gia để đi diệt những người quốc gia chân chính ở Trung Việt.

Kể từ ngày 26 tháng 2 năm 1955, một sư đoàn quân có máy bay, chiến xa và trọng pháo trợ lực, đã bắt đầu cuộc tấn công vào chiến khu Ba Lòng ở dọc Trường Sơn (Trung Việt) của những người quốc gia dám liều chết từ [missing text] ngày đình chiến Genève, lên rừng rú giành giựt lại ảnh hưởng của bọn cộng sản, để chiếm lấy chiến khu Bình Trị Thiên, bảo vệ vĩ tuyến 17.

Chiến khu Ba Lòng

Bình Trị Thiên đã nổi tiếng suốt 8 năm qua. Tám năm qua, quân Pháp đóng ở dọc biển và đại lộ quốc gia số 1 ở khu vực Bình Trị Thiên (Quảng Bình, Quảng Trị, Thừa Thiên). Còn quân Việt Minh đóng ở phía trong, miền rừng rú, dựa vào dãy núi Trường Sơn. Ở chiến khu Bình Trị Thiên, quân Việt Minh đã luôn luôn quấy rối tới châu thành Huế, và họ giữ chắc đường giao thông rừng núi để liên lạc Bắc Bộ với Nam Bộ.

Sau khi đình chiến do Hiệp Định Genève, đất nước bị cắt đôi ở vĩ tuyến 17. Quân Đội Quốc Gia chỉ chiếm đóng ở dọc biển, không lên tới miền rừng rú. Để làm cho quân cộng sản phải rút lui khỏi chiến khu Bình Trị Thiên và lên phía bắc vĩ tuyến 17, anh em quân sỹ thuộc mọi ngành cùng dân chúng và cán bộ của đoàn thể Đại Việt Quốc Dân Đảng, gọi tắt là Đại Việt chính thống (nhóm Bác Sĩ Nguyễn Tôn Hoàn)[,] phần nhiều đều là những chiến sĩ quốc gia kháng chiến Đảng [sic] đã vì chống cộng mà về [vùng quốc gia] trước [Hiêp Định] Genève hoặc không chịu tập kết và theo cộng sản ra Bắc[,] đã khởi phong trào diệt cộng, đua nhau lên rừng chiếm lại chiến khu Bình Trị Thiên. Sau mấy tháng hành quân, họ đoạt lại ảnh hưởng của cộng sản.

Nhiệm vụ của họ từ đấy là giữ vững khu rừng rú ở kế cận vĩ tuyến 17, làm bình phong che đỡ chống quân cộng tiến xuống phía nam. Nhân dịp Tết quân lực đã mạnh, Quân Đội Giải Phóng Quốc Gia Đại Việt đã chính thức làm lễ thượng kỳ, tuyên ngôn thành lập chiến khu Ba Lòng một trong các chiến khu Đại Việt ở dọc núi Trường Sơn.

Trên bản đồ, các bạn có thể nhận thấy vị trí Ba Lòng. Ba Lòng ở ngay phía tây Quảng Trị, và phía nam con đường số 9, tức là đường ăn thông từ Trung Việt sang Lào (từ Đông Hà sang Savannakhet). Tới Ba Lòng có thể đi bằng ba con đường rừng: đường số 9, đường mòn Bảo Đại, và đường mòn theo dọc sông Quảng Trị. Ba Lòng ăn thông vào miền rừng núi hiểm trở trong rặng Trường Sơn, nơi mọi sinh sống, và cũng là nơi mà một số lớn quân đội Nhật không chịu ra hàng còn ở ẩn trong đó.

Ông Diệm hạ lệnh đánh Ba Lòng

Ông Diệm vận động với Pháp để đem quân đánh Ba Lòng. Quân Đội Quốc Gia được lệnh và hoàn thành cuộc tập trung vào ngày 15 tháng 2. Tổng số quân đội dùng đánh Ba Lòng là 1 sư đoàn: 9 tiểu đoàn bộ binh, thiết giáp, trọng pháo, thêm 2 chiếc Morane trợ lực trên không. Tiếp đấy, lại thêm mấy tiểu đoàn khác ở hậu tuyến làm trừ bị.

Biết đích xác ông Diệm nhẫn tâm đánh chiến khu quốc gia Ba Lòng, chiến sĩ Đại Việt đã tung truyền đơn ở khắp các tỉnh trong khu vực đó, kêu gọi anh em binh sĩ quốc gia nhận định chính nghĩa. Lời lẽ rất rõ rệt: “Trước hiểm hoạ cộng sản, chúng ta phải sát cánh nhau để bảo vệ cho sinh tồn của dân tộc ta. Nhưng, thưa anh em, hiện nay anh em đang bị mắc mưu của một số người vì cơm áo và địa vị, bắt anh em phải chuẩn bị để tiêu diệt những thành phần các đảng phái chính trị quốc gia, như ở Nam Việt và rồi đây ở các chiến khu của Quân Đội Giải Phóng Quốc Gia Đại Việt tại Trung và Nam Việt. Ông Diệm đánh Quân Đội Đại Việt chỉ vì bác sĩ Hoàn, sau nhiều lần yêu cầu ông Diệm bỏ chính sách độc tôn để đoàn kết quốc gia không được, phải có thái độ đối lập chính trị và xuất ngoại sang Mỹ, Pháp để vận động buộc ông Diệm thay đổi chính sách. Ông Hoàn gần thành công, ông Diệm lại đánh các chiến khu Đại Việt để tiêu diệt các đồng chí ông Hoàn, xả thân lên rừng thiêng nước độc để cản đường liên lạc của cộng sản hầu ngừa một cuộc tấn công bất ngờ của cộng sản. Ông đánh Ba Lòng để bảo vệ cái ghế thủ tướng của ông!

“Hỡi các anh em, hãy phản đối lại bọn buôn máu của anh em. Riêng phần chúng tôi, bao giờ cũng chỉ có mục đích tiêu diệt cộng sản, bảo tồn lãnh thổ trong chính thể quốc gia dân chủ. Anh em hãy bình tĩnh để nhận định. Anh em đừng chịu hy sinh xương máu một cách vô chính nghĩa…”

Hầu hết anh em binh sĩ quốc gia do dự, không chịu đánh. Có những sỹ quan như Trung Tá Trung [?], đã bị triệu về, thay thế bằng trung tá khác: Trung Tá [Lê Văn] Nghiêm.

Thái độ dân chúng thì rất rõ rệt. Họ bảo 8 năm trời, chẳng quốc gia nào lo đánh Bình Trị Thiên của cộng sản. Ngày nay Bình Trị Thiên của quốc gia, thì quốc gia lại đi đánh quốc gia! Não lòng!

Đụng độ và tan hoang

Sư đoàn Quân Đội Quốc Gia tiến đến Ba Lòng theo 3 đường: 1) do đường số 9, 2) do đường mòn Bảo Đại, 3) theo đường sông Quảng Trị.

Nhiều tiểu đoàn khác và các đơn vị trọng pháo, thiết giáp trấn ở hậu tuyến phòng vệ. Các cuộc đụng độ đầu tiên đã bất lợi hoàn toàn cho quân đội tấn công: tinh thần họ lung lay bởi tình trạng “quốc gia chống quốc gia” và họ cũng không được lợi về địa thế. Cho nên Tư Lệnh [Nguyễn Quang] Hoành, đệ nhị quân khu, luôn luôn đòi viện binh.

Trong lúc ấy, tình hình khẩn trương thâm [thêm] mãi. Truyền đơn của anh em cách mệnh quốc gia tung ra khắp nơi, tiếng súng vang rền ở quanh mấy đô thị, cầu cống bị phá để hỗ trợ binh sĩ cách mệnh. Tiếng súng lại bắt đầu nổ ở Thừa Thiên ở Quảng Nam. Phong trào còn lan rộng.

Tự biết mình lầm lỡ, ông Diệm để lộ tất cả sự bối rối. Các thanh niên bị tình nghi Đại Việt bị bắt lung tung ở Trung Việt, Tỉnh Trưởng Trần Điền ở Quảng Trị bị bắt, một số rất lớn các sỹ quan bị theo dõi vì tình nghi Đại Việt. Cả đến Thái Quang Hoàng, người đã kéo quân từ Phan Rang ra đi để chống Nguyễn Văn Hinh, cũng bị nghi là Đại Việt và bị theo rõi gắt. Có lẽ hết thảy các sỹ quan ở Nam Trung Việt bị nghi hết!

Quốc gia đánh quốc gia. Não lòng. Chính sách chia rẽ và gây nội chiến còn kéo dài đến đâu?

Một công cuộc đương tiếp tục

Bây giờ chúng ta trở lại Nam Việt.

Trong khi tiếng súng nổ rào rạt ở gần vĩ tuyến 17, thì ở Nam Việt, công cuộc mà ta nói trên lại tiến hành. Trước hiểm hoạ cộng sản và mộng thực dân còn lăm le giữ các ưu quyền, đây không phải lúc quốc gia đánh quốc gia. Đây là lúc mà các khối quốc gia thực lực sát cánh lại, tiến đến một chính phủ chân thành để mọi khối đều có thể bỏ tình trạng tự trị của mình, để cùng triệt để thống nhứt bảo vệ lãnh thổ.

Đến buổi tối ngày 3 tháng 3 năm 1955 thì việc tới kết quả.

Ông Phạm Công Tắc, đại diện Cao Đài và hai ngành quân Trình Minh Thế và Nguyễn Thành Phương, ông Trần Văn Soái và ông Lâm Thành Nguyên, đại diện toàn khối Hoà Hảo, kể về [sic] đại diện khối Lê Quang Vinh, và ông Lê Văn Viễn, đồng ký bản tuyên ngôn chống lại Hiệp Định Genève và đòi hạ chính phủ Diệm, thay thế bằng một chính phủ quốc gia liên kết chân chính, dưới chính phủ mới ấy các đoàn thể tự trị sẽ bỏ tất cả quân đội tự trị của mình để lập nên thống nhứt các lực lượng quốc gia đến triệt để.

Ba giờ chiều ngày 4 tháng 3 năm 1955, đã triệu tập một cuộc hội báo, có đủ mặt các đại biểu báo chí Việt, Pháp, Anh, Mỹ. Bản tuyên ngôn đã được tung ra… nếu ông Diệm không từ chức họ sẽ dùng võ lực để triệt hạ ông Diệm. Nội loạn sắp bùng nổ! Cốt nhục sắp tương tàn!

Và, trên các ngã đường từ Lục Tỉnh về Saigon, cuộc xét bắt lại càng gắt gao. Ta chờ những biến cố đặc biệt, không thể dự đoán trước… Ông Diệm đã lung lay… Chánh sách ông đã thất bại.

Một chánh sách đã thất bại

Được Pháp đưa ra làm thủ tướng vì lúc ấy, ông Diệm là người chính trị gia duy nhất chấp nhận việc đình chiến và chia đôi đất nước. Ông Diệm đã có đủ yếu tố để thành công. Ông có toàn quyền, có tình trạng thuận tiện, không bị cộng sản và chiến tranh phá rối, được Mỹ dùng ngoại giao yêu cầu Pháp trả thêm quyền cho Việt Nam. Nhưng ông Diệm đã vì quan niệm sai lầm về chánh sách và vì tay chân thối nát mà bước lần đến thất bại.

Chánh sách phản dân chủ và độc tôn, độc tài đã chia rẽ lực lượng quốc gia. Xúi nhóm này đánh nhóm nọ. Dùng tiền di cư lung lạc các nhóm đánh lẫn nhau, đến nỗi tiền viện trợ của dân tỵ nạn hao hụt, thiếu lung tung. Dự án quốc hội rất là phản dân chủ: dân không được bầu đại diện, số người do chính phủ chỉ định quá nhiều, quốc hội là chỉ có quyền cố vấn, khác nào Hội Đồng Quốc Gia bù nhìn mở rộng. Ông Diệm lại còn sè sụt [rụt rè] không nhất định ngày thành lập. Ông nghi cả những người của ông sẽ chỉ định. Rõ buồn cười.

Nếu phản dân chủ, độc tôn, độc tài, diệt hết trọi các nhóm rồi đem lại hạnh phúc cho nhân dân, thì cũng được đi. Nhưng không có thực lực, lại đòi diệt các lực lượng tranh đấu, thì lấy đâu ra sức để tranh đấu chống cộng và giành độc lập? Nhất là ông Diệm lại sai lầm và thất bại về mọi phương diện khác.

Đây, chúng tôi xin kể:

1) Tranh đấu độc lập. Trong khi vua Sihanouk đòi thay đổi quy chế Liên Hiệp Pháp, ông Diệm làm thinh, lại còn đòi họp Thượng Hội Đồng Liên Hiệp Pháp và cử người đi Hội Đồng Liên Hiệp Pháp. (May Sihanouk không chịu họp.)

2) Chánh sách cải cách. Không có cuộc cải cách cách mệnh nào hết. Cuộc cải cách điền địa làm nửa chừng, lại không thực hiện nỗi vì không sao tạo được điều kiện an ninh. Nhóm ông Diệm cứ kể là làm thành bản nghị định cải cách điền địa, đăng trong công báo và hô trên đài phát thanh là đã cải cách xong!

3) Chánh sách bài trừ thối nát. Chỉ bắt được mấy kẻ thối nát đã mất chính quyền từ lâu. Mấy người nầy bị bắt vì bị ông Diệm nghi là có thể tranh ghế thủ tướng của ông ta. Vậy tìm thối nát đây có mục đích diệt địch thủ chính trị chứ không phải trừ hại cho dân. Nhân dân muốn chấm dứt nạn thối nát hiện nay, nhưng tay chơn của ông Diệm ăn tiền nhiều quá lại không ai bị bắt. (Xem các vụ tố cáo của báo Tổ quốc về tay chân của ông Diệm. Kết quả là báo bị đóng cửa.)

4) Chính sách quân sự. Không đem lại chi mới mẻ để tổ chức lại và cách mệnh hoá quân đội.

5) Chánh sách độc tôn. Bạc đãi dân bên lương di cư, dân Tin Lành cũng bị bạc đãi. Chủ trương tiêu diệt các đạo khác, như Cao Đài, Hoà Hảo…

6) Chánh sách dùng người. Dùng toàn người trong gia đình. Không biết nhân tài. Thái độ nghi kỵ với các viên chức cao cấp. Xua đuổi phần tử chân thành. Ông Diệm có đổ, phần lớn nhất là vì đám chân tay của ông.

7) Chánh sách ngoại giao. Ông Diệm được lợi thế nhất: thật vậy khi ký Genève, dư luận Mỹ đòi bỏ rơi hẳn Việt Nam. Chánh phủ Mỹ phải vội tuyên truyền và giúp cho ông Diệm để dư luận Mỹ thay đổi. Nhưng ông Diệm bất lực quá, đến nỗi tướng Collins bất mãn. (Xin xét lời tuyên bố của tướng Collins: ông Diệm có thực hiện được hết các chương trình, thì Việt Nam mới chỉ có 50 phần trăm hy vọng thoát nạn cộng sản. Thật là bỉ mặt ông Diệm.) Vậy mà chương trình ông Diệm lại không thể nào thực hiện, vì ngoại trừ tiền viện trợ di cư và tiền viện trợ kinh tế hàng năm, Mỹ không chịu viện trợ để thực hiện chương trình cải cách của ông Diệm nữa. (Theo báo Mỹ, Mỹ còn chờ xem ông Diệm có đủ khả năng về nhân sự, và có góp được thâm [thêm] tiền bạc nữa, thì Mỹ mới quyết định giúp.) Chánh sách ngoại giao thất bại, chỉ vì bất lực!

Chánh sách như thế, thì chia rẽ quốc gia, gây nội chiến tôn giáo là đem dân tộc Việt đến chỗ chết.

Kết luận

Chúng ta sống những ngày sôi nổi nhất. Nhiều biến cố rất bất ngờ có thể xảy ra. Tình thế buộc ta phải sáng suốt nhận định, suy xét rồi hãy phê phán.

Nhân dân đau khổ nhiều rồi. Phải có một chính phủ rất mạnh, gồm toàn thể các khối lực lượng quốc gia quanh một chương trình cách mệnh để tranh đấu, vì chỉ có một chính phủ như thế mới giải quyết được tình trạng các khối tự trị. Nội chiến chỉ lợi cho người ngoài. Không thể có nội chiến trong lúc cộng sản sửa soạn tấn công. Ông Diệm đã bất lực, không có chân tay, không có cán bộ, không có thực lực, ông Diệm đã thất bại.

Nhưng ta phải chuẩn bị. Tình thế còn phức tạp đến nỗi “rất có thể một chính phủ yếu hèn, chia rẽ và bẩn thỉu nữa ra đời. Lúc ấy, ta chỉ còn một cách: quyết liều chết khởi nghĩa khắp nơi, để đòi quyền tự quyết, để cho đất nước được sống.”

Source: Letter no. 6 written from the heart, March 5, 1955, National Archives Center II (Trung Tâm Lưu Trữ Quốc Gia II, TTLTQGII), Vietnam, Office of the Prime Minister Collection of the Republic of Vietnam (Phông Phủ Thủ Tướng Việt Nam Cộng Hòa, PThTVNCH), 14743.

THE SECESSION OF THE VIETNAMESE NATIONALIST PARTY IN QUẢNG NAM AND QUẢNG NGÃI

Just weeks after the incident in Quảng Trị, the Vietnamese Nationalist Party seceded from the SVN in the provinces of Quảng Nam and Quảng Ngãi. As the regime extended its administration into areas formerly occupied by the DRV, low level officials affiliated with the VNP carried out an assassination campaign against suspected communists without receiving permission from the central regional government controlled by Ngô Đình Cẩn. In March and April, the provincial governments cracked down on the party for the unauthorized violence, and frustrated leaders of the VNP withdrew into the foothills and formed a series of resistance zones in Ba Tơ (Quảng Ngãi), Quế Sơn, and Duy Xuyên districts (Quảng Nam). The Vietnamese National Army later attacked the zones, and the party’s last outpost fell in May 1955.

The documentary record on the unrest in Quảng Nam and Quảng Ngãi is fragmentary, and the most detailed extant accounts of the difficult relations between the VNP and the Diemist faction are by American diplomats. Reproduced below is a summary by Randolph Kidder, the embassy’s counselor and the chargé d’affaires at the time, and an attached memorandum of a conversation between John Donnell, an officer with the US Information Service, and party leader Phạm Thái. Following Donnell’s memorandum is a report by Ambassador Frederick Reinhardt about the VNP’s assassination campaign of suspected communists, though the attached enclosures with lists of names have not been included. These accounts were unsympathetic towards the VNP.

C3. Despatch 351, US Embassy in Saigon to the Department of State, April 27, 1955

Randolph Kidder and John Donnell

Subject: Conversation with leader of Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang (“Vietnam Nationalist Party”)

Enclosed is a memorandum prepared by Mr. John Donnell of the USIS at Saigon concerning conversations with Mr. Pham Thai, a prominent member of the Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang (VNQDD – “Vietnam Nationalist Party,” Vietnamese off-shoot of the Kuomintang party of China). Mr. Thai describes himself as a member of the Central Committee of the VNQDD.

While evaluation of the actual membership and influence of any of the numerous political parties in Free Vietnam is difficult because of the absence of elections or other normal channels for political expression, the VNQDD is generally considered to be substantially stronger than the run-of-the-mill “shadow parties” which proliferate among Vietnamese “intellectuals.” The VNQDD claims that its strength is concentrated principally in central Vietnam.

As will be noted from the enclosure, the VNQDD takes a dim view of Prime Minister Ngo Dinh Diem. Their particular bete noire, however, is Diem’s younger brother Ngo Dinh Can, who has resided at Hue during Diem’s tenure of office and who is accused, by the VNQDD and certain other groups, of having organized assassination cells, trafficked in offices and influence, and generally exercised an evil sway over political affairs in central Vietnam.

Subsequent to the date of the conversations described in the enclosure, unconfirmed reports have been received that the VNQDD (as well as the Dai Viet party) has begun active antigovernment resistance in central Vietnam, including the establishment of a “liberation zone” involving armed opposition to the authority of the national government.

Mr. Thai’s reported views, apart from their substantive contents, are of interest as an example of the rather primitive concepts of political action current among nationalist leaders of Free Vietnam. Such concepts date from the period of suppression of nationalist political activities under the French colonial regime, a policy which has left the noncommunist nationalist movement in Vietnam almost completely devoid of capable political theorists and leaders.

Randolph A. Kidder

Charge d’Affaires

———

Memorandum of Conversation

The following memorandum summarizes information supplied by Pham Thai, whom I have known since 1950. He claims to be a spokesman for the VNQDD party and a member of the party’s Central Committee, and has shown me clippings from Vietnam Presse and local newspapers quoting his statement on party matters.

Thai says the VNQDD is now in a difficult position because it cannot get “understanding” from the government. Thai held a secret two-hour conversation with President Diem one night about four months ago in which he proposed a “common plan” of VNQDD collaboration with the government. Diem[,] himself, however, did most of the talking. Thai had the impression Diem did not seem to understand the VNQDD proposal, although Thai repeated the details several times. Diem finally said he would consider the proposal, but when Thai subsequently called members of the Presidency staff to ascertain what Diem’s reactions were he was given vague, unsatisfactory answers.

The VNQDD proposals were, in essence, as follows:

- The Diem government must stop all hostile, suppressive acts against “nationalist” movements. Here Thai referred principally to the VNQDD but incidentally included other smaller groups such as the Dai Viet Duy Dan (which he says has limited membership and almost no popular support) and the Dai Viet group of Nguyen Ton Hoan.

- The government must work out a plan for collaboration with nationalist representatives. This would include a military phase directed at creating a national army more capable of coping with the Viet Minh threat. It would also include a political phase aimed at increasing defections from the Viet Minh and encouraging the population to move away from Viet Minh-controlled areas. These phases also would involve elimination of corrupt and inefficient civilian government employees and army officers. The VNQDD would offer services of its military officers to the National Army; replacements for ousted officers could also come from other paramilitary organizations as well as within the officer corps of the National Army. Thai told Diem corrupt, feudal, antidemocratic elements would have to go at all costs, even if this affected members of Diem’s family.

- Supervising [the] implementation of this common plan would be a high-level committee of nationalist representatives including members of the VNQDD.

Diem has reportedly remained apparently indifferent to this offer of collaboration.

Thai says Ngo Dinh Can in Hue is handing out patronage in a high-handed manner and telling his associates that the VNQDD is the first enemy, with the French and Viet Minh ranking second and third because these latter present a less immediate danger. Direct action has been taken against the VNQDD by the Diem government, particularly in central Vietnam, where the party claims to have its principal strength.

Thai cited the following example of suppressive action against his party. He said that the Tourane [Đà Nẵng] Municipal Council elected in 1953 (during the national series of municipal elections) was dominated by VNQDD men. Recently, however, a government decree summarily dissolved the elected council and new elections were scheduled. VNQDD men then began to receive anonymous letters warning them not to stand for election to the new council. One party man was shot at from behind one night but the bullet was spent and did not injure him (powder may have been removed from the cartridge so that the victim would be frightened but not hurt). VNQDD men did not run for the council and the offices all were won by government candidates.

Further differences have arisen over the subject of former Viet Minh cadres who remained in central Vietnam after the Viet Minh forces withdrew north of the 17th Parallel.

These individuals claim that they have experienced complete changes of political loyalty. Pro-Diem circles, notably Ngo Dinh Can and his henchmen, appear to take such claims at face value. The VNQDD consider these ex-Viet Minh activists to be hopelessly indoctrinated communists who are seeking opportunities to sabotage the nationalist cause, and express the fear that such elements can, under the present administration of central Vietnam, regain power and influence. The VNQDD allege inter alia that Ngo Dinh Can conducts a flourishing patronage business in government positions, and that the fact of being a former Viet Minh cadre would not lessen the influence of a candidate’s bankroll.

Thai admits that his colleagues have assassinated some sixteen individuals in central Vietnam whom they considered to be Viet Minh agents remaining in Free Vietnam for sabotage purposes. VNQDD members are now being threatened with imprisonment and trial for these activities.

Thai claims the VNQDD enjoys wide popularity in Quang Nam, Quang Ngai, Thua Thien, and the part of Quy Nhon around Tuy Hoa. He says the party could aid greatly in pacification and re-indoctrination of the population of these areas. Party popularity was retained to some extent during the years of Viet Minh activity, he says, by clandestine political activity and publication of anti-Viet Minh bulletins. Thai claims that a VNQDD chief of district and other party cadres were responsible for the reindoctrination which resulted in a recent well-publicized ceremony in which 800 former Viet Minh cadres renounced their allegiance to the Viet Minh and tore up Viet Minh flags.

As another example of what he considered government non-cooperation with the VNQDD, Thai cited the case of Cu Quoc Toan [?]. The latter, a VNQDD party man trained at the Whampoa Academy under the Chinese Nationalists, stayed in central Vietnam under the Viet Minh when the VNQDD were chased out in 1945-6. He became a Viet Minh soldier and rose to the rank of regimental commander, all the time, according to Thai, remaining loyal to the VNQDD and merely using his position in the Viet Minh army to serve VNQDD ends. After the Geneva Agreement, Toan was able to leave the Viet Minh by the simple expedient of remaining in central Vietnam after the Viet Minh left for the North. Toan was subsequently asked by Ngo Dinh Can to organize three battalions of militia, which he did. He was only paid enough to support one of them, so he supported the other two for a time out of his own pocket. Eventually he quit the job in disgust and now has asked the VNQDD Central Committee not to assign him to another post involving collaboration with the national government.

In its dilemma as to how to reduce the government pressure on its members in central Vietnam and how to induce the government to adopt lines of action such as those described in the VNQDD “common program” outlined above, the VNQDD Central Committee has recently given serious consideration to an open military uprising in the central Vietnam provinces mentioned above as its principal area of popular support. On March 21, however, Thai said the committee had decided first to try a nation-wide campaign of antigovernment leaflet distribution to try to convince the government of the extent of party organization and support. If this failed, overt action would be taken.

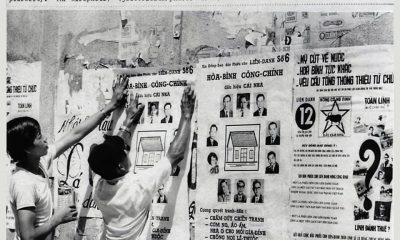

The VNQDD has distributed antigovernment leaflets during the past few months, but on a limited geographic scale. On March 26 at least two strongly anti-Diem leaflets were distributed by the VNQDD on what is claimed to have been a nation-wide scale (including Haiphong).

Thai has on occasion indicated that the VNQDD would be willing to cooperate with the government against the politico-religious sects of south Vietnam. Such cooperation, however, would apparently be effected in such a way that the VNQDD would acquire a preferred position similar in some respects to that of the sects.

Thai reports that the VNQDD has ousted Vu Hong Khanh [Vũ Hồng Khanh] from the Central Committee. Khanh was a member of the Nguyen Van Tam [Nguyễn Văn Tâm] cabinet was minister of youth and sports, at which time Thai was his chef du cabinet. According to Thai the VNQDD feels that Khanh became overly loyal to Tam and even pro-French. The reorganized Central Committee is described as composed of younger, more dynamic militants.

John C. Donnell

Saigon, March 26, 1955

Source: Despatch 351, Saigon to Department of State, April 27, 1955, NARA, RG59, CDF 1955–1959, 751G.00/4-2755.

* * *

C4. Despatch 11, US Embassy Saigon to the Department of State, July 8, 1955

- Frederick Reinhardt

Subject: Alleged government-Viet Minh collabtion against VNQDD in central Vietnam

Enclosed is a list of alleged Viet Minh officials and agents who the Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang (VNQDD – “Vietnam Nationalist Party”) charges were released from imprisonment in central Vietnam by regional authorities of the national government to aid in suppressing nationalist (i.e. noncommunist revolutionary) parties.

Use of communist agents against noncommunist, non-Diem elements has been a recurring theme in anti-Diem charges in central Vietnam. Ngo Dinh Can, brother of Prime Minister Ngo Dinh Diem, has been a particular target for such charges.

Although the enclosure pictures the government authorities of central Vietnam as undertaking to “annihilate” the VNQDD, information from other sources suggests that the Vietnamese government has been considerably embarrassed on occasion by direct action of extremist VNQDD elements against individuals they believed to be communist agents. Numerous assassinations in central Vietnam (about fifty such cases have been mentioned by government spokesmen) are ascribed to the VNQDD. Certain VNQDD personnel, in discussing central Vietnam politics with embassy officers, have in fact appeared much aggrieved that party members have been arrested merely for killing a few “Viet Minh cadres.” Particularly embarrassing for the government, of course, is the fact that such incidents can be denounced by the Viet Minh to the International Control Commission as violations of the Geneva Agreement prohibition against reprisals.

Nationalist groups such as the VNQDD can make out a fairly strong case for their claim that they have more information concerning Viet Minh organizations and personnel in various areas than the national government. Skeleton organizations of the VNQDD managed to maintain their existence and a certain amount of activity in areas thoroughly under Viet Minh administrative control. On the local level the present national government has no comparable organized source of information concerning Viet Minh low-echelon organization and operations.

The relations between the central Vietnam regional authorities under the Diem government and the principal “old nationalist revolutionary parties” (notably the VNQDD and Dai Viet) appear to have been dominated by mutual suspicion and jealousy almost from the outset. The “old revolutionaries” for their part felt that their “resistance” activities were not sufficiently appreciated and that their experience and sacrifices entitled them to substantial consideration from the government. This sentiment appears to have reached the point of a certain scorn toward those who had not shared the “resistance.”

The regional government authorities, on the other hand, felt that the “old revolutionaries” greatly overestimated their importance and (apparently) that they were of doubtful reliability from the standpoint of the Diem regime and of questionable value as political support.

The resulting hard feelings reached the point where a VNQDD group established “maquis” operations in Quang Nam province, which the government authorities undertook to repress with all available means. Spectacular results were claimed, meanwhile, by government authorities in the reformation of ex-Viet Minh agents in the area, with well-publicized ceremonies at which hundreds of such agents vowed allegiance to Diem and tore up Viet Minh flags. Such ceremonies, however, induce a certain degree of skepticism as to whether all reformations are as genuine as government authorities appear to believe. (In this connection, reference is made to Embtel [embassy telegram] 6005.)

The VNQDD further charges (Enclosure 2) that prominent members of that party were arrested in central Vietnam. A Vietnamese informant has reported that the chief of security forces for central Vietnam told him orally that orders for such arrests, during March and April, came from the “highest officials” of the Diem government. The basis for such orders may well have been a not unfounded belief that VNQDD elements, like other disaffected groups elsewhere in Free Vietnam, were interested in possible exploitation of the sect “United Front” antagonism to the government. A picturesque (although unverified) account of difficulties between the government and the VNQDD in Quang Nam is set forth in a Radio Hanoi broadcast of May 2, 1955, describing local uprisings against the government. (Enclosure 3)

Illustrative of the present governmental viewpoint is a Vietnam Presse account, on June 20, 1955, of a visit by the government delegate for central Vietnam and the province chief of Quang Nam to the Que Son district, described in the enclosure as scene of activity of several of the alleged Viet Minh cadres now engaged in repression of the VNQDD. The delegate assured a meeting at Que Son that the government would take severe measures to end the situation in which the population of the district had been for some time “victims of sabotage by a dissident faction of the VNQDD.”

Enmity between the “old revolutionary parties” of Vietnam and the Diem government holds little danger of leading to armed conflict of the magnitude of that resulting from the sect rebellion. On the other hand, these parties retain some prestige as nationalists (how much, it is difficult to assess), are organized for clandestine operations, and in some areas know better than any other nationalist elements their sworn enemies the Viet Minh. It thus appears that these parties would be useful allies in the effort to eradicate Viet Minh influence and build a strong nationalist Vietnam; on the other hand, they could constitute troublesome if not actually dangerous enemies for a government which attempted to suppress or eliminate them. The rather sketchy information available form both sides to date suggests that the Diem government is not interested in attracting the support of such parties except on its own terms. If, as alleged in Enclosure 1, the regional authorities are actually attempting to use “reconstructed” Viet Minh operatives against dissident nationalist groups in central Vietnam, they may well be harboring in their bosom an extraordinarily venomous viper.

- Frederick Reinhardt

Source: Despatch 11, Saigon to Department of State, July 8, 1955, NARA, RG59, CDF 1955–1959, 751G.00/7-855.

* * *

The VNP viewed the situation very differently, as seen in this propaganda leaflet. The leaflet was presented as an open letter to Diệm and produced by the party when its resistance zones were on the cusp of defeat. It is unknown whether the quote in the first paragraph was correctly attributed to Diệm. Nguyễn Chữ, mentioned in the letter, was a member of the VNP. The leaflet mentions a defection ceremony involving 8000 former communists. Despite the numerical discrepancy, this appears to be the same event as mentioned in document C3. Vietnam Press, the official news agency of the State of Vietnam, reported that the event took place in early March and cited the larger number.

C5. Bức thư không niêm của Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng gửi Ngô Đình Diệm ngày 9 tháng 5 năm 1955

Khi gửi cho ông “Bức thư không niêm” này, chúng tôi có ý nói chuyện với một chiến sĩ quốc gia đã từng tuyên bố khi chiếc phi cơ, từ ngọai quốc chở người ấy về cầm vận mệnh của dân tộc giữa một tình thế vô cùng gay go và bi đát, vừa hạ cánh xuống phi trường Tân Sơn Nhứt: “Không làm nô lệ cho Nga, không làm bồi cho Mỹ.”

Trong lời tuyên bố đanh thép nêu rõ lập trường của một tay kinh luân mà sự dun rủi của quốc vận đã trao cho chính quyền, tức là ông. Chúng tôi chỉ muốn đề cấp tới phần đầu: “Không làm nô lệ cho Nga.”

Vâng, kẻ thù giống nòi lúc bấy giờ và hiện nay vẫn là bọn Việt Cộng vô tổ quốc.

Trong 10 tháng nắm chính quyền ông phải đối phó với bao khó khăn mà chính sách đối nội và đối ngoại của ông đã gây ra, trong thời gian đó ai cũng thấy cái “họa phải làm nô lệ cho Nga” không những không trừ khử được tí nào mà lại có phần đè nặng thêm lên nửa nước “Việt Nam tạm gọi là tự do” này. Chắc hẳn ông không cần đòi một sự chứng minh cho điều đó, nó chỉ làm dài thêm cho bức thư một cách vô ích.

Chúng tôi muốn đề cập ngay đến sự va chạm đáng tiếc giữa chính sách của ông (hay chỉ là sự lầm lỗi của những kẻ thừa hành của ông, chúng tôi ao ước như vậy) và hàng ngũ cách mệnh của đảng chúng tôi, một đảng đã hy sinh những núi xương sông máu cho đất nước Việt Nam trong công cuộc kháng thực, diệt cộng, một đảng mà hàng ngàn vạn đảng viên đã và đương tiếp tục tuẫn quốc, quyết thực hiện cho kỳ được lý tưởng:

Dân tộc thực sự độc lập

Xã hội thực sự dân chủ.

Để củng cố chính quyền, ông đã cho lập ra nhiều đoàn thể. Trong số này có hai tổ chức: Cần Lao Nhân Vị Đảng và Phong Trào Cách Mệnh Quốc Gia đã đặc biệt lợi dụng áp lực chính quyền để bành trướng tại Trung Việt. Tuy thế, ngoài đám công chức, hai tổ chức nầy vẫn không thể thấm sâu được xuống quần chúng nông dân ở thôn quê mà sự tín nhiệm đã đặt trọng vào Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng, một đảng có thể nói là xóm làng nào cũng đã có ít nhất là một đảng viên bị Việt Cộng thủ tiêu, sát hại hay bị tù đày nhất là ở hai tỉnh Quảng Nam, Quảng Ngãi!

Vì vậy chính quyền Trung Việt đã có manh tâm làm cho tan rã và loại trừ hàng ngũ cách mạng của chúng tôi, điều này chính người của chính quyền là ông Giám Đốc Công An Trung Việt Nguyễn Chữ đã phải nhiều lần công nhận như vậy với các thân hào, nhân sĩ miền Trung.

Cuộc tảo thanh vì ganh tị đó, chứ chắc chắn không phải vì đối lập, vì một điểm trong chính sách của ông là diệt cộng kia mà (!), và vì hàng ngũ chúng tôi đã xung phong diệt cộng ở Quảng Nam, Quảng Ngãi là ổ của Đệ Tam Quốc Tế, một cách vô cùng tích cực như kết quả thu hoạch được đã chứng minh. (Xin nhớ lại cuộc tẩy não cộng sản và cuộc lễ ly khai đảng cộng sản của 8000 đảng viên cộng sản đứng dậy xé tan cờ búa liềm và cờ đỏ sao vàng do ông Nguyễn Đình Thiệp, một đồng chí của chúng tôi thực hiện được tại quận Quế Sơn, Quảng Nam, cách đây độ 3 tháng, có phóng viên ngoại quốc đến quay phim…) Cuộc tảo trừ vì ganh tị đó đã khai mào vào cuối tháng 3 dương lịch vừa qua: Rất nhiều cán bộ địa phương của chúng tôi (con số 400 có lẽ chưa kịp sự thật) mà phần nhiều giữ những vai trò quan trọng trong chính quyền hay xã hội như: chủ tịch, thư ký hội đồng dân cử tỉnh, thành, giáo sư, chỉ huy trưởng lực lượng cảnh bị, quận trưởng, hội viên hội đồng hương chính, thân sĩ v.v… đã bị chính quyền Trung Việt bắt giam và tra tấn với những phương pháp tàn nhẫn học được của lũ quỷ Việt Cộng. (Một đồng chí của chúng tôi chịu không nỗi kìm kẹp đã phải nhảy xuống giếng để tự vận tại Hội An, rất nhiều người khác thân thể bị phế hoại vì tra tấn, đương chờ tử thần trong cảnh xiền xích và lao lý!)

Trước sự khủng bố phản dân quyền và dân tộc đó, dân chúng đã đứng dậy họp mết tinh ngày 6-4-1955 và liên tiếp nhiều ngày sau, trên 20 địa điểm, kết tập trên 200,000 người, để phản đối và đòi trả lại tự do cho các chiến sĩ quốc gia đầy thành tích đấu tranh kia. Chính quyền miền Trung đã giả điếc trước dư luận quần chúng vô cùng phẫn nộ, lại tiếp tục bắt bớ, khủng bố đồng chí của chúng tôi, nên toàn thể hội viên các hội đồng hương chính cùng nhiều quận trưởng đã phải ly khai chính quyền để phản đối và rút vào nhiều khu để tự vệ. (Phong trào ly khai đó hiện vẫn còn sôi nổi tiếp tục lan rộng.)

Chính quyền địa phương đã tổ chức nhiều cuộc hành quân để đàn áp chúng tôi mà lớn nhất là cuộc hành quân ngày 22-4-55 với sự tham dự của nhiều tiểu đoàn. Súng của chính phủ đã bắn vào chiến sĩ cách mệnh chân chính. Máu con cháu tinh thần của vị anh hùng dân tộc Nguyễn Thái Học đã đổ một cách vô lý, không phải vì súng đạn của thực dân hay Việt Cộng mà vi súng đạn của một chính quyền hăng cao rao là “cách mạng quốc gia” mới thực là oái oăm và mỉa mai biết mấy.

Chúng tôi tin rằng, nếu ông đem tất cả thiện chí để thực hiện 2 điều nói trên, thì trên đường giải phóng dân tộc khỏi ách thực cộng đánh đổ phong kiến để thiết lập một nền dân chủ thực sự, cải tạo xã hội cho đúng theo trào lưu tiếp hóa của nhân loại, thì chắc chắn ông và chúng tôi sẽ gặp nhau giữa lòng dân tộc.

Được như vậy thì may mắn cho tiền đồ của tổ quốc biết bao nhiêu!

Kính chào chân thành cách mạng, chân thành dân chủ,

Ngày 9 tháng 5 năm 1955

Trung Ương Đảng Bộ

Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng

Source: Open letter from the Vietnamese Nationalist Party to Ngô Đình Diệm, May 9, 1955, TTLTQGII, PThTVNCH, 30387.

You may like

Nguyên Ân Revives the Portrait of Phan Khôi Once Again

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 22 – Subjects and Sojourners

“First Thắng, Second Chinh, Third Thanh, Fourth Trưởng”: The Four “Incorruptible” Generals of the ARVN

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 21 – Living Abroad

Toward National Buddhism: Thích Nhất Hạnh on Buddhist Nationalism and Modernity in the Journal Phật Giáo Việt Nam, 1956-1959 (Part 2)

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

National Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoChina’s Recent Invention of “Nanhai Zhudao” in the South China Sea (Part 2: Examining the “Nanhai Zhudao” legal basis)

-

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)