After 1975

Striving for a Lasting Peace The Paris Accords and Aftermath

Published on

Editor’s Note: The death of Henry Kissinger on November 9th of this year rekindled many conversations about this role and legacy in the Vietnam war. Either revered or hated, Kissinger’s role as the secretary of state had lasting, incalculable reverberating effects on the outcome of the Paris Peace Accords and, consequently, Vietnam as a country. However, conversations surrounding Kissinger’s impact often gloss over the myriad of different perspectives from Vietnamese political leaders that would ultimately shape the course of South Vietnam. In recognition of Kissinger’s passing and of these imbalances in perspectives, the following is a chapter from The Republic of Vietnam, 1955–1975: Vietnamese Perspectives on Nation Building written by South Vietnam’s former Minister of Information, Hoàng Đức Nhã.

…

Hoàng Đức Nhã served in the government of the RVN soon after returning from his studies in the United States in January 1965 with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. He was a telecommunications engineer at the Ministry of Interior, then a project engineer at the Industrial Development Bank of Vietnam. He joined President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu’s staff in October 1967 soon after the latter was inaugurated as president, first serving as policy analyst—when he developed the framework of the land-reform undertaking—and later as private secretary (chief of staff) and concurrently press secretary to the president. As private secretary Nhã was also a main advisor to President Thiệu in the Paris negotiations. After the peace agreement was signed in January 1973, Nhã joined the cabinet as minister of mass mobilization and open arms and coordinating minister for nation building. He resigned in November 1974 over policy differences with the prime minister. From 1975 to 2003, Nhã worked at three major companies, General Electric, FMC Corporation, and Monsanto Company. In mid-2004 he cofounded and served as CEO of a company specializing in big data analytics serving Fortune 100 companies and various U.S. government agencies. He retired in 2012 and now lives in Chicago.

…

I returned to Saigon in early January 1965 after three and half years of study in the United States, where I had obtained a bachelor of science degree in electrical engineering. I had great expectations to be an active participant in the nascent industrialization of the South Vietnamese economy.

As a scholarship recipient trained abroad, I had agreed to work for the government upon graduation. I first spent a year as a telecommunications engineer, followed by another year as a project engineer at the Industrial Development Bank. But the majority of my time was spent being seconded to work as a staffer to the minister of economy.

It was in that assignment that I got to understand the importance of sound macroeconomic planning and vigorous implementation of practical plans, in order to avoid the pitfalls of centralized planning and white elephant projects that developing nations usually fell in love with. Upon returning from an additional four months of specialized training in the United States on the management of development projects, I found myself back at the Industrial Development Bank ready to put into practice what I had learned. Shortly after that, in early September 1967 South Vietnam held the first presidential and National Assembly elections of the Second Republic, a momentous development for the country, and a turning point in my career.

How I Got into Politics

Nothing in my studies or training had prepared me for what I would be asked to do shortly after Mr. Nguyễn Văn Thiệu was inaugurated as the first president of the Second Republic. Soon after assuming office, President Thiệu created a kind of brain trust, formally designated the Office of Experts, to assist him in policy and issues analysis and crisis management for all nonmilitary issues. I was invited to join and promptly left the Industrial Development Bank.

There were ten of us in the brain trust; nine were graduates of French and Vietnamese universities, and I was the only one trained in the United States. I took over the portfolio of agricultural reform, and within three months submitted a framework for both narrowing the social divide in the rural areas between landowners and tenant farmers, and increasing rice production for self-sufficiency. This later formed the basis of our Land to the Tiller land-reform program (see chapter 4 in this volume).

Shortly after the 1968 Tết Offensive, I was promoted to personal secretary to the president, a kind of sounding board and analyst to the president on key issues. This was a highly political job, normally reserved for a much more senior person with knowledge and experience in the political workings of the country. I was twenty-five at the time.

As personal secretary I participated in all the major decisions the president made, and as the pressure grew to achieve a peaceful solution to the war, I was front and center in all the discussions, at first as a behind-the-scenes strategist. Then, starting in early 1972, I burst onto the scene at the side of the president, much to the surprise and then consternation of the Americans. Few political observers in Vietnam knew who I was or why the president had given me such an important position.

I was soon thrust into the heat of the battle, so to speak, and became a key witness to history, and a participant in the tumultuous relationship between President Thiệu and President Richard Nixon and his national security advisor Henry Kissinger.

The Meandering Road to Peace

During his inauguration as the first president of the Second Republic in early October 1967, President Thiệu swore to defend the constitution promulgated a few months earlier, to safeguard the territorial integrity of South Vietnam, and “to open the door and leave it open” to a lasting peace, in order to implement programs for the betterment of the South Vietnamese people. This promise was indeed a tall order, considering that the country had just come out of a tumultuous phase of its political evolution and was dealing with an ally who, after having Americanized the war, now wanted to Americanize a solution to end it.

President Thiệu inherited a country at war, wracked by political turmoil and instability and a sagging morale in the population. The bloody coup that ended the First Republic on November 1, 1963, was followed by an interregnum period when the generals jostled for power and not much progress was made. The ensuing domestic turmoil and lack of leadership within the military junta emboldened politicized Buddhist monks and other political and religious groups to clamor for change.

President Thiệu realized that the country needed a broader political base to offset the negative consequences of the last years of the First Republic and the chaos during the interregnum years. He also realized that in order make the people of South Vietnam more engaged in the fight to protect and develop the homeland, he needed to win their hearts and minds. This meant bringing the war to a peaceful end as soon as possible and leveraging that peace to build a stronger nation in South Vietnam. The daunting task facing him was further compounded, on the one hand, by a relentless war of aggression waged by North Vietnam in violation of the 1954 Geneva Accords and, on the other hand, by an ally, the United States, that began to unilaterally implement an exit strategy.

President Thiệu realized that the march to American disengagement was irreversible. Even before he was elected president on September 3, 1967, he became aware of U.S. intentions when, in March 1965, President Lyndon Johnson declared that he was “ready to go anywhere, at any time, and meet with anyone whenever there is a promise of progress toward an honorable peace.” One month later, President Johnson stated that he was ready for unconditional discussions and promised aid to Southeast Asia, including North Vietnam. Johnson further hinted that the United States would not oppose a coalition government in South Vietnam and that he was willing to stop all aerial bombardment of the North.

At the December 1967 Canberra Conference, Johnson increased the pressure by “suggesting” to newly elected President Thiệu that he engage in direct talks with the National Liberation Front (NLF), Hanoi’s proxy in the South. President Thiệu was worried that the United States was slowly Americanizing the peace process. However, he agreed to negotiate with North Vietnam when, on March 31, 1968, President Johnson shocked the world by announcing the halt of bombing in North Vietnam to facilitate negotiations with Hanoi and his decision not to seek a second term in office.

President Thiệu approved this peace process but also cautioned the Johnson administration that the roles and responsibilities between the United States and South Vietnam in the peace negotiations should be clearly delineated before talks began. He was understandably worried that Washington would negotiate over South Vietnam’s head, similar to what had occurred during the 1954 Geneva Accords. Fortunately, the success of South Vietnam’s armed forces in defeating the 1968 communist Tết Offensive gave us a position of strength going into the negotiations.

Mounting Pressure to Negotiate Fast

At the July 1968 Honolulu Summit between the United States and the Republic of Vietnam (RVN), the two sides agreed to require North Vietnam to withdraw its forces from South Vietnam before the United States began to depart. The United States also promised not to support the imposition of a coalition government in South Vietnam. Two weeks prior to arriving in Honolulu, President Thiệu said in a press conference that the RVN was willing to shoulder a bigger burden of the war starting in 1969, so that the United States could begin withdrawing troops while at the same time increasing its economic and military support to South Vietnam.

The Paris negotiations between the United States and North Vietnam that began soon after March 1968 produced no results, while Hanoi continued massive infiltration to make up for losses incurred during the Tết Offensive. Nevertheless, the United States continued to show flexibility pursuing a settlement, and the upcoming American presidential elections further increased the pressure on us to engage in direct talks with the NLF while Washington negotiated with Hanoi in a separate forum.

But President Thiệu refused to meet with the NLF, because we had still not agreed with the United States on our common objectives in Paris, let alone the issues that the talks would cover, or their procedures. For us, these negotiation procedures were of paramount importance.

Our refusal to send a delegation to the Paris meeting infuriated the American side, especially Defense Secretary Clark Clifford and Ambassador William Harriman, the head of the U.S. delegation. The Johnson administration, and most of the American media, thought that South Vietnam had been influenced by Mrs. Anna Chennault, apparently on behalf of the Nixon campaign, who had asked us not to attend the Paris talks until after the election. Even President Johnson, in his memoir, alludes to this rumor.

Mrs. Chennault indeed met with two South Vietnamese officials, our ambassadors to the United States and to Taiwan (the latter was President Thiệu’s older brother). The information she gave them was passed on to President Thiệu, who then conferred with some of his inner circle. I took note of her message, but insisted that before we sent our team to Paris, we needed to have our strategies and plans clearly defined and developed, as well as a joint modus operandi with the American delegation.

Furthermore, after Tết, South Vietnam was winning on the battlefield, and we believed that we should negotiate in a position of strength. The RVN government was further incensed when Secretary Clifford, in a December 1968 interview, stated that the United States need not work out common positions with the Vietnamese allies. It was not until mid-January 1969 that North Vietnam, under pressure from Moscow, caved on the important procedural issues for the talks. We then sent our delegation to the Paris talks in January, now expanded to include both the RVN government and the NLF. The October 1968 skirmish with the United States on negotiation strategies and tactics was a harbinger of the many more disputes to come.

Building the Nation while Bracing for the Negotiations

After the 1968 Tết Offensive, the South Vietnamese government and people were very encouraged by the successes of our military campaigns and by the initiatives launched by the president in his quest to strengthen the nation. We repaired infrastructure that was destroyed by the fighting and also developed other capabilities that were essential to our nation-building efforts. Among the most challenging tasks were the building of a democratic system as prescribed by the 1967 constitution based on the respect of basic human rights and the rule of law, and the implementation of plans for developing both a market economy and our agriculture in order to increase productivity, create a new middle class, and improve living standards.

South Vietnam has abundant resources, and a population blessed with entrepreneurial spirit and hard work. Our education system, along with scholarships for gifted students to be trained at overseas universities, had produced a class of well-trained technocrats who were critical to the success of our nation-building efforts (see chapter 8 and chapter 9 in this volume about developments in South Vietnam’s education system).

The South Vietnamese government at that time was in a unique and challenging situation. On the one hand, we had to defend our territorial integrity and defeat the communist invasion, and on the other hand, we had to create transformational change for the betterment of the entire population. We did all that while cooperating with the Nixon administration to restore peace to the two parts of Vietnam.

It was quite a daunting task. But little could we predict that our so-called unified negotiating position with the United States was being constantly frayed by secret exchanges and communications with Hanoi. Relations gradually took a turn for the worse when we realized that President Nixon and Dr. Kissinger wanted to end the war their way, South Vietnamese opinions or objections be damned.

Rocky Journey to a Peace Accord

The peace negotiations were conducted by the White House. President Nixon and Dr. Kissinger had effectively sidelined the State Department under Secretary William Rogers. It was also clear to us that the White House rarely updated the leadership of the House and Senate, if at all, except for a few selected representatives and senators, and some friendly commentators and reporters.

On the South Vietnamese side, President Thiệu consulted with the leadership of our own House and Senate. He also relied on a well-coordinated National Security Council composed of Vice President Trần Văn Hương, Prime Minister Trần Thiện Khiêm, Chairman of the Joint General Staff general Cao Văn Viên, Minister for Foreign Affairs Trần Văn Lắm and Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs Trần Kim Phượng, Special Assistant to the President for Foreign Affairs Dr. Nguyễn Phú Đức, and myself, as personal secretary to the president and spokesperson.

Not once had we thought that the American side, in its haste to arrive at a solution, would run the negotiations by themselves without consulting us. The first skirmish happened on May 14, 1969, when President Nixon, without first confirming with President Thiệu, publicly advocated the simultaneous withdrawal of American and North Vietnamese forces from South Vietnam. This was a clear departure from an agreement, adopted by all troop-contributing countries in 1966, that allied forces would only withdraw six months after the North had pulled out of the South.

President Nixon also advocated the participation in political life by all political elements in South Vietnam, including the National Liberation Front—without giving credit to a similar proposal that President Thiệu had already made the previous month. After we communicated our dismay to the U.S. embassy in Saigon, the White House quickly moved to reassure President Thiệu by proposing a June 1969 meeting between the two presidents at Midway Island in the Pacific, half way between Washington D.C. and Saigon.

The communiqué from this one-day summit meeting reiterated the American view that only the South Vietnamese people could determine their political future and that there would be no coalition government in South Vietnam—another promise that was to be tossed away years later without prior consultation. In turn, we reiterated our offer to begin replacing American forces with South Vietnamese troops, beginning with the withdrawal of twenty-five thousand U.S. soldiers.

Most galling at Midway was that the Americans did not bother informing us that in order to fast-track the negotiations, it was already laying the foundation for secret talks between Dr. Kissinger and the leaders of the North Vietnamese delegation, Xuân Thủy and later Lê Đức Thọ. Declassified materials show that the first secret talk between Dr. Kissinger and Xuân Thủy took place on August 4, 1969, at the Paris apartment of Jean Sainteny, the former French delegate general in Hanoi. These materials also show that at the meetings, Dr. Kissinger made many important concessions, especially on the political issues in South Vietnam that should have been the purview of our government and the NLF.

We followed the Midway meeting by proposing free and fair nationwide elections, but Hanoi rejected our proposal. Meanwhile, the phased withdrawals of American troops continued. On July 25, 1969, President Nixon introduced the “Nixon Doctrine,” and thus launched the “Vietnamization” program. A few days later during a visit to Saigon, he pledged his steadfast support for South Vietnam and promised not to make any further concession to Hanoi. The next two years were marked by a series of proposals from the United States and the RVN aimed at breaking the diplomatic stalemate, but Hanoi continued to stonewall, believing that Nixon would eventually abandon South Vietnam to get U.S. troops and POWs back home in order to secure reelection.

North Vietnam’s Fight Fight/Talk Talk Approach

After years of stalled negotiations, 1972 was a year of tectonic political and military changes, the results of which in many ways sealed the fate of South Vietnam. The year began with the January 9 revelation by President Nixon that Dr. Kissinger had been conducting secret talks with Hanoi since August 1969. The talks had been conducted without consulting with or informing South Vietnam. This shocking turn of events was followed by Nixon’s dramatic February visit to China. He and Dr. Kissinger hoped to implement triangular diplomacy, using China as leverage against Russia, Russia as leverage against China, and both of them as leverage against North Vietnam.

However, Hanoi broke off the Paris talks, opting to end the war militarily with a decisive victory. In April, the communists launched a three-pronged offensive against us: across the northernmost provinces of Quảng Trị and Thừa Thiên; through the Central Highlands; and past the town of An Lộc, a mere sixty miles from Saigon. The Easter Offensive, or, as we called it, the “Fiery Summer” (Mùa hè đỏ lửa), saw North Vietnam deploy thirteen combat divisions, leaving only one division in the North as a reserve.

After some initial setbacks, our forces regrouped, and with the help of massive American air and naval bombardment, we slowly repelled the invaders, retaking most of the captured territory by the middle of July. President Nixon decided to bring North Vietnam back to the negotiation table, and in a May 9 address to the nation, he announced Operation Linebacker—the massive bombing of the North, and the mining of Haiphong harbor.

A Decent Interval

One of my responsibilities as personal secretary to the president and presidential spokesperson was to monitor and analyze American and international media, in order to detect clues about what was being floated concerning a potential settlement. We knew that the Americans liked leaking information on the negotiations, through deep backgrounders or quotes attributed to “sources close to the administration.”

And by that time, through American press coverage and talks with journalists, key members of the U.S. National Security Council, and staffers in the U.S. Congress as well as members of Congress and senators on visit, I had begun to pick up on a balloon being floated in Washington about a “decent interval” concept for ending the war. According to this concept, the United States would settle for the fall of South Vietnam—provided it occurred only after a “decent interval” had passed following the final withdrawal of American troops.

Having launched Operation Linebacker, Nixon then headed to Moscow for a summit meeting with Leonid Brezhnev, the leader of the Soviet Union, and his foreign affairs minister Andrei Gromyko. Here too, Dr. Kissinger tossed around the concept of a decent interval, using such words as “a degree of time,” “eighteen months,” or “a year or two.” Soon after the meeting, Gromyko informed Hanoi that the United States favored a political solution that did not guarantee a communist victory—but did not exclude it.

Then, in July, Kissinger returned to China. Here, he apparently reassured his host that after the implementation of a cease-fire in Vietnam, the United States would withdraw all its remaining troops and POWs and, after a decent interval, refrain from intervening in the political situation in the South. This time, he did not attempt to quantify the decent interval, instead using words like “sufficient” or “reasonable” to describe his intentions. After Kissinger left Beijing, Hanoi’s chief negotiator Lê Đức Thọ also paid China a visit, where he was apparently instructed by Prime Minister Zhou Enlai to drop his insistence on President Thiệu’s removal.

While all these high-stake maneuvers were being played out in secret between Nixon and Kissinger, Brezhnev and Gromyko, and Mao Zedong and Zhou, the Paris talks remained stalled. Dr. Kissinger told us only that there was little movement in the secret negotiations and that Hanoi was still being intransigent.

Our side showed good will and made many more concessions on key points in order to quickly reach a negotiated settlement. But when we asked whether our proposals had been passed on to the North Vietnamese, the Americans replied only that “the other side will not accept it.” Still, although we were miffed at not having direct contact with the North, our leadership always assumed that the United States would have our interests in mind in their dealings with Hanoi.

Showdown in Saigon

Shortly after Dr. Kissinger’s June trip to Beijing, the Paris negotiations seemed to have taken on new life—much of it hatched behind the backs of President Thiệu and his government. Reality literally barged in when the American ambassador Ellsworth Bunker informed us that Dr. Kissinger would visit Saigon on October 19 to review our mutual position on the political settlement. We had no inkling that during this visit, he would present us with a near-complete ready-to-be-initialed agreement between the United States and North Vietnam.

I had, however, received a tip about what Dr. Kissinger planned to discuss with us. Two days before Kissinger’s arrival, the chief of Quảng Tín (a small province south of Đà Nẵng) called me with a serious report about a document found on a dead North Vietnamese soldier. It contained instructions for North Vietnamese troops operating in the South on how to prepare for an impending cease-fire and the formation of a coalition government in South Vietnam.

I immediately went to see President Thiệu in his private quarters to report on this dramatic development. I recall telling him that something was being cooked up behind our backs and that Washington and Hanoi must have agreed on a deal. I then briefed him on the possible ramifications of such an agreement. He asked point blank whether I thought the Americans had “gone in the night with the communists,” using a popular Vietnamese saying for when one party keeps another party in the dark about its intentions. I told him that with all this smoke, “there must be a fire somewhere,” and that we had every reason to suspect foul play from our ally. We decided not to inform the rest of our national security team, as we wanted them to walk into the meeting with their eyes open and their minds not shrouded with suspicion.

On the morning of October 19, President Thiệu received Dr. Kissinger and his team in a calm and collected manner in the situation room next to his office. I was also present, serving as the National Security Council secretary and taking notes. Later, I would brief the rest of the cabinet and the leaders of the National Assembly on our deliberations with the American delegation. And then President Thiệu and I would have one-on-one discussions, conducting post mortems and planning our next moves.

President Thiệu kept the Americans waiting while we huddled in his office, making sense of a telephone conversation I had had with Arnaud de Borchgrave of Newsweek, who phoned just before Dr. Kissinger arrived at the palace. Arnaud told me that he had rushed in from Hanoi after interviewing North Vietnamese prime minister Phạm Văn Đồng about a deal Dr. Kissinger had apparently concluded with Hanoi a few days earlier. During the interview, Phạm Văn Đồng had mentioned a “transition coalition,” and Arnaud had asked me if we planned to accept it. Needless to say, I was on high alert after the tip-off from Arnaud, just one day after finding the document on the dead North Vietnamese soldier.

Dr. Kissinger and his delegation were surprised to see me at the meeting, because my name had not yet featured in their profiles of President Thiệu’s advisors. He proceeded to present what he described as a most comprehensive agreement to end the war and restore peace to Vietnam. He further claimed that the deal was a total collapse of the bargaining position that Hanoi had clung to for so many years. Incredulously, Dr. Kissinger even told us that the North Vietnamese leaders had cried after consenting to the provisions of the agreement!

After many more reassurances about the merits of the deal, and a message from President Nixon promising not to abandon South Vietnam, Dr. Kissinger asked us to review and approve the draft agreement so that he could take it to Hanoi to sign in three days’ time. It was as if he was telling us, “Well gentlemen, this is the best deal we can hope for, and you are not going to have a better one!” It was so incredible that I could not help but shake my head after Dr. Kissinger finished his monologue.

We were shocked that the draft text of the agreement they gave us was in English, and we asked for a Vietnamese copy that arrived only four hours after the meeting ended. President Thiệu asked Dr. Kissinger for clarification on a few points, and I asked him about the timeline of his path forward. He replied that he intended to return to Hanoi by October 23 at the latest, in order to have them initial the draft. It was not lost on us that the deal was meant to be announced before the American elections. Not that President Nixon needed this development to secure his victory, with the polls showing him well ahead of George McGovern, the Democratic presidential candidate.

President Thiệu thanked Dr. Kissinger and told him we would have our comments ready the next day. He then instructed me, his special assistant for foreign affairs Nguyễn Phú Đức, our ambassador to the United States Trần Kim Phượng, and Phạm Đăng Lâm, our ambassador to France and concurrently chief of the South Vietnam delegation to the Paris talks, to analyze the agreement and report back.

The meeting adjourned with nary a smile on our side. The four of us analyzed the deal over lunch and immediately lost our appetites after reading through it.

Basically, we were being asked to end the war on Hanoi’s terms. The United States had agreed to pull its troops from the South even as North Vietnamese forces stayed behind. All POWs were to be exchanged and repatriated, and a coalition government was to be imposed, disguised as an “administrative structure for national reconciliation and national concord” that would organize elections to determine the future of South Vietnam.

The four of us briefed the president, and all he said was that it was the first time we had even heard of such a deal and that all our proposals and counterproposals had evidently been tossed out by the Americans and North Vietnamese. He then instructed me to carefully analyze the Vietnamese text and report back. I spent almost three hours going through the Vietnamese version and identified sixty-five issues, a dozen of which we considered deal breakers. The deal was dramatically different from what we had been discussing with the United States for the past two years.

We were particularly shocked to see that the draft agreement referred to only three countries in Indochina—Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos—instead of four, with South Vietnam included. There was no mention of the demilitarized border zone stipulated by the 1954 Geneva Accords on Vietnam. There was also a clause according to which North Vietnamese troops did not have to withdraw from South Vietnam, even though the Americans were compelled to depart. Most offensive to us, however, was the provision for a de facto coalition government in South Vietnam, composed of representatives from our government, the NLF (Hanoi’s proxy), and the independent South Vietnamese opposition groups collectively known as the Third Force.

That evening, I met again with the president to discuss my analysis of the agreement. We both realized the Americans were getting out of South Vietnam on terms entirely advantageous to the United States and North Vietnam, leaving an uncertain future for the people of the South.

The next morning, the four of us along with Minister for Foreign Affairs Trần Văn Lắm met with Dr. Kissinger and his team at the foreign minister’s private residence. President Thiệu meanwhile was consulting with our military commanders and province chiefs to discuss the battlefield situation, where the enemy was racing to capture as much land as possible before the anticipated cease-fire.

The session at the foreign minister’s house only increased our apprehension about the draft agreement. We became even more suspicious after the American side tried to explain glaring mistakes in the document as mere typing errors, and new demands by Hanoi as minor points that the United States had unsuccessfully attempted to have removed.

The following day, October 21, President Thiệu and our national security team met with the Kissinger delegation, which was told that South Vietnam could not accept the agreement. The Americans responded, reiterating the same arguments they had already given the previous day. Then at Dr. Kissinger’s request the general meeting adjourned for a private session format that included President Thiệu, myself, Dr. Kissinger, and U.S. ambassador Ellsworth Bunker.

October 22 saw two additional tense meetings among the four of us, with no substantial movement from either side. President Thiệu once again insisted that he could not accept the deal as currently proposed. By now, Dr. Kissinger was growing impatient, aware that the window to visit Hanoi was quickly fading.

He asked for another meeting with President Thiệu after a quick dash to Phnom Penh, apparently to reassure Prime Minister Lon Nol that the agreement was good for the people of Vietnam. This kind of outreach activity was also being conducted in Saigon, with American personnel promising various political groups that the deal meant an honorable and lasting peace and that President Thiệu had already approved.

Back from Phnom Penh that afternoon, Dr. Kissinger and Ambassador Bunker went straight to the presidential palace, again hoping to convince President Thiệu to sign. The meeting was quite tense, and I will never forget Dr. Kissinger’s remark to me that my boss should not try to become a martyr!

When it became clear that he would have to return empty-handed, Dr. Kissinger asked President Thiệu for yet another meeting on October 23. When we asked why we should meet again, Kissinger explained that he wanted to leave the impression that there was still movement in our discussions.

Spinning a Debacle

On October 23, at 8 AM, we again received Dr. Kissinger and Ambassador Bunker. The president asked Dr. Kissinger to give President Nixon a personal letter explaining why he could not accept the deal as it stood. Before taking leave, Dr. Kissinger cautioned us not to reveal the details of our discussions over the past four days.

As I accompanied him out of the president’s office, Dr. Kissinger remarked to me that the visit had been the worst failure of his political life and that he would not be returning to South Vietnam. I replied that he would be most welcome anytime. But all I got was a grumble!

President Thiệu and I immediately conferred on our next moves, agreeing not to reveal all the details of our meetings with Dr. Kissinger and Ambassador Bunker to the rest of the national security team. I said to President Thiệu that we should assume the Americans would spin the mini debacle in their own way and that we must avoid being portrayed as obstructing peace by refusing to cooperate. The Americans, I warned, were sure to use deep backgrounders and non-attributable quotes to explain their side of the story.

After debriefing the rest of the national security team, the president and I started to draft a nationwide televised address to be delivered that evening. Without describing the agreement in detail, we explained our position on a political settlement with the communists and insisted that on a number of critical issues, we would never surrender. The speech was very well received by the people and in our National Assembly.

Reaction came swiftly from Hanoi, however, which released the text of the deal the following day, forcing Dr. Kissinger to hold a press conference explaining the impasse, during which he declared that “peace is at hand.” This earned a rejoinder from the North that “peace is at the end of the tip of the pen,” while I merely opined to the press that as far as I knew, war was still around the corner.

Put Up . . . or Die

The next few months saw our exchanges with the Americans becoming angrier, with rather unusual diplomatic language. True to his word, Dr. Kissinger did not return to Saigon, instead appointing Ambassador Bunker to serve as his messenger. General Alexander Haig, Dr. Kissinger’s deputy, did visit Saigon though, and in his meetings with President Thiệu and me, he tried to cajole and coerce us, threatening “brutal action” in order to force the president to accept the deal.

In the meantime, Hanoi refused to negotiate, continuing its military offensive throughout South Vietnam. It took the 1972 Christmas Bombing campaign to force them back to the table, where they eventually agreed to some of the key changes we had been requesting. Meanwhile President Nixon sent us many letters promising continued assistance to South Vietnam, while threatening to go it alone and cut off aid should we refuse.

We faced a situation where further American or North Vietnamese concessions were unlikely. But with assurances of continued U.S. assistance in the postsettlement period, and a commitment to a full-force U.S. response should Hanoi violate the treaty, we signed the deal on January 27, 1973.

Hard Times Ahead

The peace accords proved to be a Pyrrhic victory for South Vietnam. North Vietnam soon began to violate the agreement, which forced us to respond, leading to increasingly violent military confrontations combined with foot-dragging at the negotiating table over the implementation of the agreement.

Unfortunately for us, the U.S. Congress was now controlled by the Democratic Party, increasingly taking over foreign policy from the executive. The 1973 War Powers Act and Case-Church Amendment further tied President Nixon’s hands. As a result, the Nixon administration did little to respond to North Vietnam’s violations, despite the promises from President Nixon to President Thiệu. More ominously still, the American military did not even lift a finger when, in January 1974, the Chinese Navy attacked our forces and seized our Paracel Islands off the coast from Đà Nẵng.

Our challenge was further compounded after the Watergate scandal incapacitated President Nixon. Ironically though, until his resignation, he did his best to reassure us that the United States would continue providing aid so we could defend ourselves and would react strongly against communist violations of the Paris Accords. Concurrently, the U.S. embassy in Saigon and visiting White House officials all insisted that the United States would not waver in its promise to help South Vietnam.

Throughout all this I was practically the sole dissenter in the South Vietnamese government, arguing that we needed to chart a different course of action because there was no guarantee that the United States would honor its commitments, with or without President Nixon. I could not substantiate my hunch about a “decent interval” with any profound fact-based analysis. But from my unscientific gauging of the mood in America through radio and television reports, I could sense that we were rapidly losing the support and assistance we desperately needed.

Meanwhile, American military and economic assistance was shrinking by the day, and it looked to us like the Democratic Party was exacting revenge for our alleged role in defeating the Democratic nominee for president in 1968. Additionally, general amnesia in the American media and the indifference of key congressional leaders killed off any efforts to provide us with more aid.

Psychological Warfare

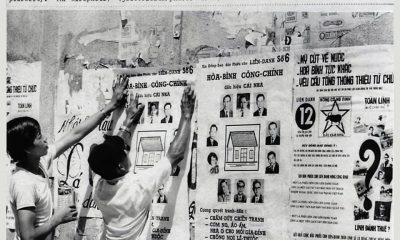

Against this backdrop, our government still had to defend against continued communist violations of the treaty terms. And President Thiệu also had a nation-building agenda to pursue. Of particular importance was the battle for the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese people, so that they could contribute positively to the undertaking, ready for the new political reality of nationwide elections stipulated by the Peace Accords.

One week before signing the peace deal, President Thiệu tasked me with preparing the country for psychological warfare with the communists in the South. I had to quickly formulate effective new strategies to enlist the population in this psychological struggle, while continuing the Open Arms program whereby we appealed to communist soldiers and cadres to join our side.

I drastically transformed our rather static approach to engaging with the population, urban civil society in particular, opting for a more dynamic and time-sensitive model. I hoped to explain to the people the government’s plans and programs to build a democratic society based on the rule of law and respect for human rights, and to fast-track agricultural and industrial development to improve their livelihood.

I reorganized the existing Ministries of Information and Open Arms by formulating new strategies and developing correct plans to fulfill the mission of reaching out to the people. Those two ministries were traditionally staffed with members of whatever political party happened to run them, so cronyism and nepotism were rampant. I replaced them with well-trained personnel, graduates of our universities and the National Institute of Administration. I then integrated the two ministries into a single department, the Ministry of Mass Mobilization and Open Arms, which I managed for nearly two years after the peace deal.

At the same time, I initiated an aggressive global information and outreach campaign, setting up information centers in Washington D.C., Paris, London, and Tokyo. They were staffed with experienced bilingual diplomats and communications experts, capable of rapidly responding to new developments. We did all this with a very modest budget.

We faced an indifferent and often hostile media in the United States and received little attention from key leaders in a Congress that had deliberately turned against the Nixon administration, refusing to fulfill his promises to South Vietnam. The fact that the executive branch had not even sent the Paris Peace Accords for Congress to ratify made the situation more dire each day.

But we marched on and executed our programs enlisting international support, while countering similar efforts from Hanoi. We scored a few impressive public relations victories by exposing their treaty violations and their indiscriminate shelling that caused the deaths of innocent people, including in some cases young school children. I had always worried that we were too reliant on American promises made in secret exchanges and confidential conversations rather than through concrete measures.

Aftermath

Immediately after we signed the Peace Accords, I advocated a more self-reliant course of action. We needed this to cope with a violent war of Northern aggression, shaky morale among our own troops, dwindling aid from an ally we could no longer trust, and a foreboding sense of imminent U.S. abandonment once the decent interval had run its course.

But our commitment to nation building remained strong: on the one hand, defending the country and its people from the aggressors, and on the other hand, upholding the constitution and making the government smaller and more efficient in providing services to the people. We strove to rally the people, our soldiers, and even cadres from the other side to join us, while managing our dwindling resources to promote economic development.

Yet nobody in the cabinet, least of all Prime Minister Trần Thiện Khiêm, wanted to believe my concern that the decent interval could indeed transpire. With convincing assessments from my staff at the overseas information centers I had created, I now could build a stronger case, albeit with some anecdotal evidence, that the United States would not abide by its commitments and that we needed to chart our own course while publicly insisting that the Americans keep their promises.

Our biggest mistake had been continuing to believe that America would stand by us. Now, we had to respond to the new world order between Washington, Moscow, and Beijing, where American troops and POWs were on their way home to their families. Sadly, most of our cabinet and our generals continued to blissfully and unrealistically hope that Nixon’s pledges would be kept. For advocating self-reliance and warning that we should not put too much faith in American promises, I became the bête noire of the Kissinger team in Washington and the new U.S. ambassador in Saigon, Graham Martin.

I sensed that President Thiệu was torn between soothing assurances of support from the American leadership and his fears that the decent interval would indeed come to pass. Even key members of his staff put their faith in American promises, and pressure mounted on him to fire me—so I made his decision easier by offering to resign late in October 1974.

The president did not want to appear as though he had caved on American demands to dismiss me, so he disguised the move as a change in cabinet, replacing three additional ministers at the same time. I felt terrible that Minister of Trade and Industry, Nguyễn Đức Cường, Minister of Finance Châu Kim Nhân, and Minister of Agriculture Tôn Thất Trình had become collateral damage in my removal.

I watched helplessly and very painfully as South Vietnam spiraled downward, fast and furious. I felt no gratification assisting President Thiệu in writing his resignation speech, when he told me that I had been right not to trust the United States.

Like most South Vietnamese who love their country, I still nurse the pain and sorrow of my homeland’s demise. And I still ponder what might have happened if our Churchillian plea to “give us the tools, and we will finish the job” had been answered.

You may like

-

“The Common Place of Law” in the “Uncommon” World of Vietnamese Immigrants: The Vietnam War Refought in Massachusetts

-

Interview with Father Le Ngoc Thanh: Faith can change the world.

-

Love Found and Lost: The Kim Vui’s Story (Book Review)

-

Creating the National Library in Saigon (excerpt)

-

Upcoming Event: 5/10/23 Hidden Histories: The South Vietnamese Side of the Vietnam War

-

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 14 Vietnamese Anticommunism

Frustrated Nations: The Evolution of Modern Korea and Vietnam

Lại Nguyên Ân Revives the Portrait of Phan Khôi Once Again

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 22 – Subjects and Sojourners

“First Thắng, Second Chinh, Third Thanh, Fourth Trưởng”: The Four “Incorruptible” Generals of the ARVN

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 21 – Living Abroad

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

National Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoChina’s Recent Invention of “Nanhai Zhudao” in the South China Sea (Part 2: Examining the “Nanhai Zhudao” legal basis)

-

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)