After 1975

Depression in the Elderly Population of the Vietnamese Community in Orange County, California Part 3/3

Published on

Editor’s Note: This work was written by Huyen Duc Duong and originally edited by Duong Nhu Nguyen and Nhu Duc Dzuong. For readability, the study has been edited for style and is published as the last of a three-part series. For the purpose of furthering academic inquiry, the US-Vietnam Review will publish works such as the following, however, please be advised that the Review does not endorse all contextual interpretation herein.

PART 3: METHODOLOGY FOR CASE STUDY

Description of research

The case study that provides the basis for this paper used quantitative research to explore the prevalence of depression among the elderly Vietnamese community in Orange County, California. Orange County is considered the capital of Vietnamese Americans, with the largest concentration of such ethnic population. The 15-item ODS Short Form (Geriatric Depression Scale) was used to assess depression om the sampled group.

Design

For this research, a cross-sectional survey was designed and used to interview participants, in order to determine the prevalence of depression among elderly Vietnamese immigrants as represented by the cross-section. Those Vietnamese individuals at and above the age of 50, from three social groups selected at random at three designated community centers, were invited to participate in the study. Participation in this study was completely voluntary.

Subjects

The target pa1ticipants in the study was a convenience samp1e of 100 elderly Vietnamese individuals aged 50 and above, attending chi-kong exercises in three centers of Vietnamese Seniors in Garden Grove, Westminster, and Santa Ana. The number of male subjects was 50 and the number of female subjects was 50. The mean age was 66.30 years.

Measures

For this research, a sociodemographic questionnaire and Short Version of Geriatric Depression Scale were presented in Vietnamese for participants to answer.

—The Sociodemographic Questionnaire: This questionnaire was developed for the purposes of gathering research participants‘ information on demographic variables including age, gender, marital status, education completed, financial status, social support network, and the helping-seeking behavior of depression.

—The Vietnamese Short Version of Geriatric Depression Scale (Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986): This instrument consists of 15 closed-ended items in which participants answered Yes or No to questions used to access their depression level. The Vietnamese version of the scale has been found to have 92% sensitivity and 89% specificity (Kurlowicz, 1999).

- The 15 closed-ended questions:

- Are you basically satisfied with your life?

- Have you dropped many of your activities and interests?

- Do you feel that your life is empty?

- Do you often get bored?

- Are you in good spirits most of the time?

- Are you afraid that something bad is going to happen to you?

- Do you feel happy most of the time?

- Do you often feel helpless?

- Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing new things?

- Do you feel you have more problems with memory than most?

- Do you think it is wonderful to be alive now?

- Do you feel pretty worthless the way you are now?

- Do you feel full of energy?

- Do you feel that your situation is hopeless?

- Do you think that most people are better off than you are?

- Allocation of points. (See Exhibit)

Procedure

All participants selected at random (within the designated minimum age of 50 and above and limited to the three designated centers) were invited to participate voluntarily in the study. Participants were assured of their anonymity and absolute confidentiality of their responses and their completed survey questionnaires. Survey objectives and questionnaire instructions were read to all participants prior to the survey administration. Participants completed the questionnaires within a 60-minute class session. Answers to questionnaires were carefully double-checked for completeness and responsiveness. Data collection was done after respondents finished the questionnaire. For absolute confidentiality, all survey questionnaires were destroyed by the researcher upon completion and result tabulation of the study.

PART 4: ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION

Findings

- Participant Demographics

- Gender.

The sample consisted of 100 elderly Vietnamese participants in which 50 males and 50 females were drawn at random from three senior centers in Orange County, California, who voluntarily participated in the study. Those selected at random but refused to participate were not included in the study.

- Age.

There were 50 % (n=50) men and 50 % (n=50) women who made up the sample. The average age of this sample was 68 years, ranging from 50 years old to 86 years old with a mean of 6.6.30 years.

- Marital status.

Six % (n=6) were identified as single living with their families, 7% (n=7) separated, 74 % (n=74) married, and 13 % (n=13) widowed.

- Education.

As a group, 11 % (n=l 1) attended elementary school, 16 % (n=16) completed Junior High, 26 % (n=26) completed High School, 25 % (n=25) attended some college, 6 % (n=6) had a BA or BS degree, 2 % (n=2) attended graduate school, 5 % (n=5) had an MA or MS degree, and 9 % (n=9) had an MD degree. (Table 1 below)

| Variable | IN | I Mean | I Minimum | I Maximum | |

| Age | 1100 | I 66.30 years | I 50 | I 86 | |

| Variable | N | Percentage % | |||

| Gender | 100 | 100 % | |||

| Male | 50 | 50 % | |||

| Female | 50 | 50 % | |||

| Variable | N | Percentage % | |||

| Marital status | 100 | 100 % |

| Single | 6 | 6% |

| Separated | 7 | 7% |

| Manied | 74 | 74% |

| Widowed | 13 | 13 % |

| Variable | N | Percentage % |

| Education | 100 | 100 % |

| Elementary school | 11 | 11 % |

| Junior school | 16 | 16 % |

| High school | 26 | 26 % |

| Some college | 25 | 25 % |

| BA,BS | 6 | 6% |

| Graduate school | 2 | 2% |

| MA,MS | 5 | 5% |

| MD | 9 | 9% |

Table 1: Participant Demographics.

- Prevalence of Depression.

Amongtl1e sampled participants, 33 % (n=33) were identified as slightly depressed, 16 % (n= 16) severely depressed and 51 % (n=S l) as non-depressed. (Table 2 below)

| Vaiiable | N | Percentage% |

| Prevalence of Depression | 100 | 100 % |

| Mild Depression | 33 | 33 % |

| Severe Depression | 16 | 16 % |

| Non-Depression | 51 | 51 % |

Table 2: Percentage of Depression.

- Way of Coping.

Of the sampled participants, 14 % (n=14) said that they would seek a doctor for their depression; 38 % (n=38) would consult with their family members, 33 % (n=33) would consult with their friends; 9 % (n=9) would do nothing, and 32 % (n=32) would find other ways to deal with their depression. (Table 3 below)

| Variable

in Percentage Way of Coping |

100 | 100 % |

| Seek a Doctor | 14 | 14 % |

| Consult with family members | 38 | 38 % |

| Consult with friends | 33 | 33 % |

| Do nothing | 9 | 9% |

| Other | 32 | 32 % |

Table 3: Way of Coping

Discussion

Interpretation.

The quantitative data collected were used to examine the prevalence of depression among the elderly population in the Vietnamese community in the Orange County, California. Based on the convenience sample described above, it was found that (i) 33 % of the sampled participants were identified as slightly depressed, in which the female percentage was higher than male (female %:20 % and male%:13 %); and (ii) 16 % were severely depressed with the same percentage for both sexes (female%: 8 % and male%: 8 %). So, the number was 49 % clinically depressed with female percentage being higher than the male group (female%: 28 % and male%: 21 %). This total finding number is higher than that reported in previous studies of other elderly Vietnamese populations throughout the United States. For example, in the study conducted by Dr Tuyen Nguyen, among sampled Vietnamese participants, the number of clinically depressed participants was 21 % in Orange County, California (Nguyen et al, 2006). It was also found that 17% of Vietnamese immigrants in Boston were clinically depressed, in the study of Nelson et al (Nelson, Bui, and Samet, 1997). The Boston study also found that only 38% of the sampled members consulted with their family members as a way of coping with their depression. This finding conforms to the norm of the Vietnamese culture — that each individual strives to be the pride of his family. Many are sufficiently embarrassed by what they consider to be the stigma of mental illness and feel the same about their symptoms of depression, such that they are unwilling and unable to discuss their feelings with others or professionals, except with their own family members, and even so, the number did not show that the majority of depressed elderlies chose to share their feelings and symptoms with their own family. Mental illness is considered a very sensitive and taboo topic, a sign of weakness in character. As a result, many Vietnamese elderlies resist seeking professional help for their depression. In this case study, only 14 % of the sampled participants sought a medical doctor as a way of coping when they got depressed and felt hopeless.

Limitations.

This case study was based on a non-probability sample because it did not truly include a random sample. For convenience, the sample was deliberately drawn from the three senior centers in Orange County, California, in which participants were attending ”Chi-Kong” exercises to improve their health.

Further, the sample obtained for this study is not truly representative of the whole Vietnamese American aging populations because the study contained only individuals who lived in the Orange County.

Therefore, the result cannot be generalized to other elderly Vietnamese immigrants across the United States.

Last but not least, the time that these Vietnamese participants spent in the United States is not the same for all participants; thus, the experiences of challenges, assimilation, and life style were different in the sample, and no correlation or trend could be drawn in that regard. Such correlation or trend in depression can particularly be harder to recognize in Vietnamese elderlies, since English barrier, cultural behavior, and assimilation depend on the length of time spent in the U.S. However, it can be recognized that those Vietnamese immigrants who do not speak English and face more hardship in assimilation seemed to be more under-diagnosed than those who speak English well and can assimilate to the American life more quickly.

Evaluation.

Despite the case study’s limitation, the findings made in this exploratory research showed that depression was prevalent in the sampled elderly Vietnamese immigrants who lived in Orange County, California, and that intervention is needed urgently.

There are at least two obvious reasons to pay attention to these signs of depression according to the Short-Form Geriatric Depression Scale, and to instigate intervention immedidately:

First and foremost, these signs of depression cause suffering and debilitation just like physical pain. Second, at its extreme, depression can be a killer. As long as someone recognizes the problem, modern treatment becomes more effective with receptiveness, and such treatment can be made available more urgently.

A real case involving a famous Vietnamese elderly — a former Republic of Vietnam officer and political prisoner in communist Vietnam’s “re-education” camp — can be mentioned as demonstration of this critical and urgent need.

See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NZOwlJ0UuLQ.

The cite was the tape of an arranged visit by U.S. journalists to Communist Vietnam’s “Re-education Camps” in the late 1980s, prior to full implementation of the Reagan-Bush Humanitarian Operation program that enabled the resettlement of former South Vietnamese political prisoners in America).

The tape showed American journalists’ visit to one of those camps where former South Vietnamese officers were detained to be ‘re-educated’ for their “crimes against the people.” There, the entourage of American journalists and cameramen were allowed to interview a selected number of camp detainees in prearranged activities filmed by the U.S. media crew. The interviewees did not say much, as they were “busy” being filmed by American journalists in a library containing the complete editions of Lenin’s thoughts, a visit by one detainee with his wife and daughter who brought with the detainee two live chickens and dried vermicelli to cook at the camp), and a

music band of a few detainers playing what seemed to be rock and roll on their guitars. Everybody spoke little but smiled with self-consciousness.

The last detainee interviewed by the American journalists was an invalid, one-legged former RVN officer who identified himself as formerly holding the rank of “major.” This interviewee did not smile.

The camera captured his disability: he sat on a surface, but it was obvious that he had only one leg. (Later information circulated in America among the refugees established that this filmed invalid detainee was formerly the military chief (quận trưởng) of the famous-infamous Cu Chi district, where the Ho Chi Minh trails ended on the territory of South Vietnam. (Ho Chi Minh trails were the secretive underground and inner-mountain paths that sent Northern Vietnamese soldiers to the South for infiltration and combat.) This detainee had lost his leg (past the knee) in Cu Chi combat, yet after the fall of South Vietnam, he was still imprisoned for “re-education” by the winners from the North.

During the interview, at first, this invalid detainer remained silent and did not answer the journalists’ questions about life conditions in the camp. He expressed his answer non-verbally by the sullen expression and the fierce sadness in his eyes, together with his unwillingness to smile, speak, or even look at the camera (he was filmed sideway). His eyes were those of the sufferer and the defiant who would not complain and would not yield. The eyes said it all and the journalist understood, pressing more questions. When pushed for an answer whether he was given “enough food” to eat in the campe, he looked away, retorting in fluent, structured English that he did not know the meaning of “enough,” and that detainees were supposed to find their own “food.” He stopped there. The journalist then asked the last question: whether the detainee had a message for President Reagan. This time, the invalid interviewee finally spoke up to the camera, and spoke with resolution. He stated slowly with carefully chosen words that all prisoners in these camps wanted and deserved freedom, and that the “freedom world” out there needed to bring detainees like him out of these camps as soon as possible.

When the visit and interview was aired on network TV in the U.S., the invalid prisoner of conscience – the RVN major and former Cu Chi military chief – became famous among the refugees as the unknown hero of “reeducation camps,” who courageously sent the message of “freedom” to President Reagan in front of prison guards. Viewers might remember him because of his words and the expression in his eyes and on his face, but few knew his name or identity except for his fellow officers who might have recognized him on screen.

Naturally, later on, as part of Reagan-Bush HO program, this one-legged former RVN officer arrived in the U.S. Like many of his colleagues and fellow countrymen, he took residence in California. Plagued with old age, rapid health deterioration and compounded physical illnesses after years and years of hard labor under harsh conditions and oppression, this hero of communist “reeducation camps” eventually committed suicide in California, leaving a suicide note taking full responsibility for his action and explaining why – in short, his despair of feeling useless on the land of “freedom,” such that all hope of rebuilding life and regaining meaning and purpose had become “too late.” The news of his death was modestly and poignantly announced in a California-based Vietnamese radio program for those who knew him and those who had seen the network program in America.

Because he was not a participant in the case study here, and there was no publicly released diagnosis of depression, his name is withheld from this paper on account of privacy. For those who had seen him on the network TV show, he remained the unnamed tragic hero of the Vietnam War.

The practical lesson learned about the plight of Vietnamese elderlies and aging, ailing survivors of Vietnamese communist “re-education camps is self-evident from this tragic and poignant story.

Overall conclusion from the case study

The Vietnamese community in Orange County, California is a heterogeneous group reflecting a diversity of educational, political, socioeconomic, and religious backgrounds, as well as different migration histories. The forces of modernization, urbanization, industrialization, and especially cross-continent immigration in the aftermath of an atrocious war have changed the culture in exile, as well as the structure and functions of the Vietnamese family system. Experiencing horrific past events and a drastic change of living environment undoubtedly lead to serious blatant and latent mental health problems, many of which remain unknown, belittled, disregarded, or simply unnoticed. Despite the limitations of data gathering and research studies, depression emerges as a legitimate and critical concern in the Vietnamese senior-citizen population in the United States and in the global diaspora. Therefore, more research must seriously be pursued and problems addressed.

This case study serves to call attention to this painful problem, in hopes of helping readers understand the cause of depression as well as the need for treatment for Vietnamese elderlies. Improved recognition and treatment of depression in late life will make those years more enjoyable and fulfilling for the depressed person, his or her family, and caregivers. Without a sense of happiness for the victims and survivors of war in their later years, the wounds of the Vietnam War are still bleeding, and sufferings continue in prevalent ways, even if they may occur in silence and in neglect.

Summary of implications

This study does not provide definitive answers to the etiology of depression in Vietnamese elderlies, nor proposing adequate solutions. It does offer, however, relevant information about the psychological correlates of depression. As already noted, the change of living environment, the prolonged effect of PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), role reversals, and language and cultural barriers can lead to serious depression in the Vietnamese elderly in Orange County. As reported earlier, according to this study, the prevalence of depression in Vietnamese immigrants is at the rate of 49 % with female percentage being higher than the male group (female%: 28 % versus male%: 21 %). Depression can be particularly hard to recognize in Vietnamese elderlies, because some of its more insidious symptoms (such as fatigue, loss of appetite, and disrupted sleep pattern) can also be caused by, and are often blamed on, other physical illnesses. In the past, what we may now recognize as depression was often dismissed by patients and even doctors as “a normal reaction to getting old.” Detecting depression in the first place is the most critical step. This case study hopes to raise awareness toward fulfilling such first step. As long as someone recognizes the problem, modem treatment becomes available and can be more more effectively achieved. The study also pointed out that only 14 % of the sufferers consulted with a medical doctor as a way of coping with their depression. This means that either effective health care is not available, or the stigma of mental illness is still embedded forever in the Vietnamese mindset and among the elderly population.

What do older people do to lead a happy, fulfilling and peaceful later life, and to improve their life satisfaction? It is important for individuals to adopt a more positive attitude, and that cannot be achieved without family and community support, together with cross-cultural understanding in the health care community. It is important for family and community members to be trained and educated on how to help the victims: Simple messages such as the following can be asserted and reasserted as part of such support mechanism, or simply as expression of individual caring and love: try not to get discouraged, it will take time for depression to lift, get involved in activities that make older people feel good, exercising three or five times a week in short duration or even moderately, regardless of physical impediment (at least 30 minutes each time is a good goal). Relaxation exercise is another effective way to fight depression. A healthy diet can also improve the way older people feel on many levels. Eating more vegetables is the best way to increase nutrients and limit fat and excess calories that can lead to other health problems. Get enough sleep because it improves attitude and gives older people more energy for being physically active and coping with emotional stress. Medication is always the last or necessary resort.

In sum, education and support network are absolutely important factors in improving the recognition of depression and facilitating the proper treatment choices for Vietnamese elderlies. These efforts should be community and family-initiated as part of overcoming cultural isolation and disconnection. Public education about mental illnesses should be publicized in Vietnamese or newspapers, radio, television and the internet so that Vietnamese elderlies and their families and friends may recognize the need for changes within their current condition and any future recurrence of depressive symptoms. Information regarding nutrition, exercise, and even medication or ultimately electroshock therapies should be talked about to remove stigma. Group therapeutic discussion sessions can also help community and family members understand depression and treatment choices in order to enhance the victims’ self-esteem, as well as to develop alternative and appropriate strategies for handling life stress and conflicts of roles and cultures. Finally, understanding the need for professional counseling at all levels, in all related matters, is a positive step toward effective treatment. It would take several generations to overcome the impact of war, the disintegration of nationhood, and the uprooting of culture. As the English playwright John Heywood has said, “Rome wasn’t built in a day, but they were laying bricks every hour…Rome wasn’t built in a day, but it burned in one.”

###

Frustrated Nations: The Evolution of Modern Korea and Vietnam

Lại Nguyên Ân Revives the Portrait of Phan Khôi Once Again

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 22 – Subjects and Sojourners

“First Thắng, Second Chinh, Third Thanh, Fourth Trưởng”: The Four “Incorruptible” Generals of the ARVN

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 21 – Living Abroad

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

National Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES4 years ago

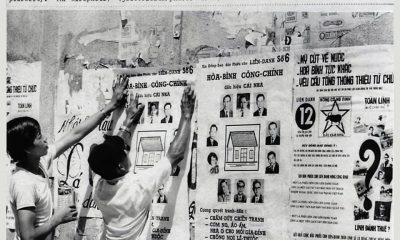

ARCHIVES4 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoChina’s Recent Invention of “Nanhai Zhudao” in the South China Sea (Part 2: Examining the “Nanhai Zhudao” legal basis)

-

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)