Politics & Economy

Trần Văn Tùng’s Vision of a New Nationalism for a New Vietnam (excerpt)

Published on

By

Yen Vu

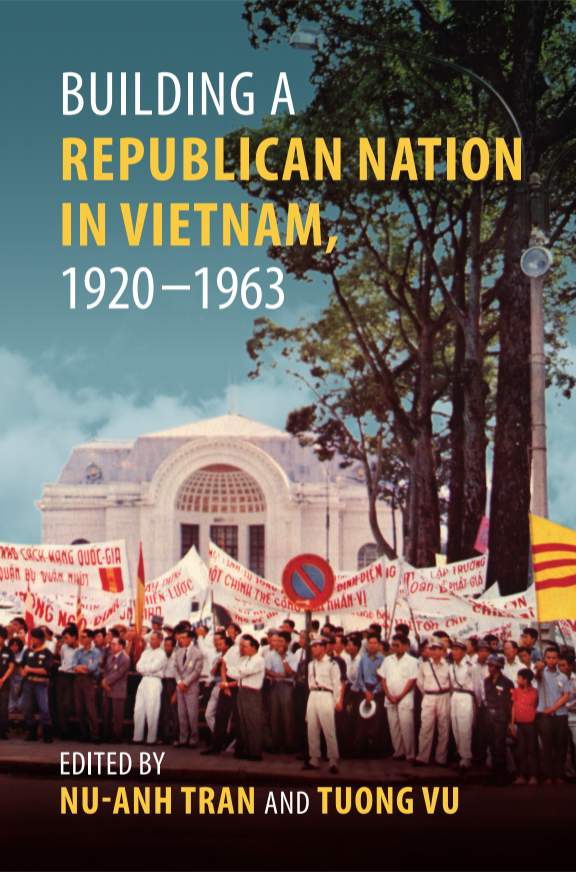

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from chapter 4 of Building a Republican Nation in Vietnam, 1920-1963, edited by Nu-Anh Tran and Tuong Vu, University of Hawaii Press (2022). The text has been redacted for style and readability. Please refer to the volume for the full text. To purchase the volume, please click here.

Trần Văn Tùng’s Vision of a New Nationalism for a New Vietnam

What is a nationalist? It is simply a conscious and lucid man,

open to all new ideas, who, rejecting all individualism and anarchy,

advocates the Nation as the first form of a human society. –Trần Văn Tùng

In a letter to the editor in the New York Times in 1953, Vietnamese essayist and historian Trần Văn Tùng publicized his position on liberty and independence for Vietnam. These were the founding tenets for his understanding of nationalism, one that would be distinct from the communist movement. In his letter, he acknowledged the American global anticommunist strategy but also its idealism and pointed out that foreign aid, though perhaps well-intended from both the French and Americans, “[has] not clarified the Vietnamese situation, which appears more unstable than ever.”[i]

This is because any foreign aid cannot grant Vietnam the most powerful weapons of all: independence and liberty. In other words, independence was something to be developed from within, not granted by another power. This letter would be the first of several addressed to the American public over the course of a decade in which Trần Văn Tùng would declare his political ideas, introduce the existence of the Democratic Party of Vietnam, and establish early on a difference between the independence of the anticolonial Vietnamese revolution and the independence he sought as a nationalist.[ii]

Trần Văn Tùng is not a figure we hear about often in a political context. He is instead better known for his literary works of francophone literature, notably for the titles Rêves d’un campagnard annamite (1940) and Bach Yên, ou, fille au coeur fidèle (1946), both of which have also been recognized by the French public, if not by the French Academy then by journals such as Lettres françaises and scholars such as Paul Claudel. Any existing scholarship on Tùng’s writings have predominantly treated his work within the limits of colonial or Franco-Vietnamese relations.

These sparse works either categorize him as the obedient Vietnamese student or scholar or see little connection between Tùng’s poetics and politics, leaving little room for the depth of plans he intended for Vietnam.[iii] His literary corpus therefore has yet to be examined using the political lens through which they were written or his diplomatic activity explored with the same conviction that afflicted the writer regarding the internationalization of the Vietnamese nationalist cause.

On the one hand, studies of the Francophone figures such as Trần Văn Tùng remain in the context of French and Francophone literature, which therefore do not place him within the larger context of Vietnamese culture and the changing politics of the twentieth century. Conversely, scholars of Vietnam do not include these writers within studies of Vietnamese nationalism.

This chapter thus contributes to both the fields of Vietnam and French studies and draws connections that are important for better understanding not only these intellectual figures but also the Vietnamese historical and political contexts that surrounded them. In proposing to examine the works of this writer turned diplomat, I turn in particular to his idea of nationalism, expressed in his later works, and its ambivalent relationship with the legacy of republican ideals.

In the context of Francophone North Vietnamese intellectuals, Tùng was an engaged intellectual who could be likened to Nguyễn Mạnh Tường, whose formation in law and literature greatly influenced his participation in politics in North Vietnam. The latter, educated in France, applied his Western education to make social criticisms under the Vietnamese communist party, and is most known for his contribution in the journal Giai phẩm in 1956. That is, although he initially supported the party’s efforts to rebuild society after colonial independence, their increasing infringement on individual and intellectual freedom made him, along with many other writers and intellectuals, critical of the direction the party was headed.

Despite the different contexts in which they operated, their political stance could be traced back to a similar liberal, humanist standpoint, in which freedom, and especially intellectual freedom, was the foundation of a functional society and should thus be protected. Ironically, both intellectuals would find their pursuit of such freedom interrupted; Nguyễn Mạnh Tường excommunicated for expressing his candid critique of the Land Reform campaign in 1956, and Trần Văn Tùng relegated to political “noise” from abroad.

Among the categories of noncommunist, nationalist revolutionary movements in South Vietnam, which included the Đại Việt parties, the Catholic and Cần Lao party of the Ngô family, the southern political and religious parties, and the republican and democratic parties, it is precisely this last category that has received the least attention in scholarship.[iv] As a proponent of the Democratic Party of Vietnam, Tùng sought an anticommunist, anticolonialist, and anti-Diệm alternative. His ideas for a free, sovereign nation, though perhaps only made public to the American readership beginning in 1953, had already been set in motion, reflected upon, honed, and developed at least a decade earlier with the publication of his novel Bach Yên.

It was not until the Elysée Accords of 1949, signed by former Emperor Bảo Đại and French President Vincent Auriol promising Vietnam independence, that Tùng began to write explicitly on this topic. Tùng subsequently released four consecutive essays on Vietnam published exclusively with Editions de La Belle Page in Paris from 1950 to 1953. The first three of these are most similar in kind and address nationalism directly; the last is a collection of Vietnamese legends that ground Vietnamese identity and nationalism in folklore.

These essays most likely speak to an educated elite whom Tùng believed to be both responsible and capable of reconstructing a new nation. After these essays were published, Tùng started actively communicating with the American and French public about Vietnam, its people and its politics, particularly during the last years of the Diệm administration. These essays thus mark his transition into politics, but with the authority and respect of a “poet in touch with his native country,” as one prefacer claims, rather than an ambitious politician.[v]

Focusing on the political perspectives that inform Tùng’s writings, I examine in particular his vision for a new nationalism as it unraveled after the 1949 Elysée Accords, its local and international appeal, and its program for a free and democratic Vietnam. This includes a critical examination of the republican legacies in Tùng’s idea of new nationalism as well as a discussion of the Democratic Party of Vietnam that emerged overseas, to be distinguished from the party founded in 1944 that later merged with the Việt Minh. As a consequence, we can appreciate a more complex understanding not only of Trần Văn Tùng, but also of Vietnamese nationalism, not to be conflated with communism nor aggregated in the general category of anticolonialism.

Disaggregating Ideas of Vietnamese Nationalism

Much of the discussion on Vietnamese nationalism, despite overlap with Vietnamese narratives, has been dominated by external or academic views. For example, the vicissitudes of how scholars understand nationalism reflect both American involvement in Vietnam and the ways in which the field has changed in the last fifty years. We might understand nationalism during the final decades of colonial rule in Vietnam in terms of binary oppositions between those in favor of independence and those for further collaboration, or even between communist and anticommunist movements.

After 1945, nationalist parties such as the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng were quickly extinguished as a collective entity and the idea of nationalism soon became conflated, both in scholarship and by political actors, with the anticolonial and anti-imperial position offered by communism, the reconstruction of the nation after independence monopolized by communist strategies. Such was the understanding of many Americans, swayed by the antiwar movement, who saw Hồ Chí Minh and his party first as nationalists and only then as communists fighting for a self-determined government.

. . .

Disaggregating ideas of Vietnamese nationalism is complex; it requires not only the distinction between communist and nationalist struggles but also the acknowledgment of differences between the various nationalist movements. It prompts seemingly obvious questions: Did being “nationalist” mean patriotic? Did it automatically include advocacy for independence? Was nationalism committed to the ethnic identities of people, or was it state-centered?[vii] Was it an end goal or part of the process of becoming a nation? Different political groups had different answers to these questions, and such plurality, or “contested nationalism,” has been one proposed way to understand the complexity of Vietnam’s trajectory as both a single and partitioned nation.[viii] During the thirty years of continual shift in Vietnam’s geopolitical boundaries and statuses, the negotiation of Vietnamese nationalism also reflected those changes.

Vũ Văn Thái, the director general of foreign aid and budget under the Diệm administration and subsequently Vietnamese ambassador to the United States in 1965, captures in one essay that unfixed quality of nationalism by writing, “Independence alone is an empty proposition. It has to be accompanied by a concept of nationhood which would both fulfill the rising expectations of the people, and at the same time preserve the essentials of the Vietnamese way of life.”[ix] As we see for Thái, it is unclear what that concept would be.

Writing on Vietnamese nationalism in 1966 for the journal Vietnamese Perspectives, he claims that the Vietnamese nation was getting closer than ever to fruition. Even despite being critical of the Diệm administration, for example, he still acknowledges the optimism and pride of the people in seeing a constitution for an independent Vietnam proclaimed in October 1956 for the first time. In noting such progress, Thái allows us to make two important observations. First, nationalism is both an ideal to be achieved as well as something that required conscious reflection and work. Second, the commitment to responding to the people’s expectations underlines the representative and democratic quality of that process.

Although no clear relationship between Thái and Tùng as individuals has been established to date, their writing to foreign audiences reflects similar conceptions of nationalism. This allows us to make some inferences about how educated intellectuals, particularly those abroad, might understand the fate of their country. Like Thái’s, Tùng’s understanding of nationalism also drew on a process that required constant reflection while being committed to an end goal, what he calls “the law of perpetual becoming.”[x] However ambiguous it may be, that goal would entail both the preservation of a Vietnamese identity and a response to the people’s needs.

He never explicitly defines nationalism, but we find in his essay Le Vietnam au combat (1951) that Vietnamese nationalism is quickly associated with a discussion of basic rights: “They [the Vietnamese people] claim the right to rule themselves, according to their own aspirations . . . Do you not find this to be in our most basic right? The right to exist, to live?”[xi] Vietnamese nationalism is also inseparable from a love for one’s country that leads one to surpass oneself, defeat enemies, to harbor a “tenacious will to live and to be.”[xii] In relating the will to live and survive together as a kind of raison d’être, Tùng’s view of nationalism is also unmistakably philosophical. What then makes Tùng’s nationalism “new” and how does he imagine it applied to the reconstruction of Vietnam, as early as 1950?

. . .

Where Tùng’s nationalism overlaps with republicanism is in the democratic ideals and humanist philosophies that underlie his advocacy for freedom and the need to respond to basic rights of the people. He rejects corruption and inherited systems and rules and instead emphasizes liberty, especially as the young generation embraces it. Although he does not explicitly address social critiques of capitalism and inequality, it is precisely in the abstract quality of the individual that he negotiates this relationship with republicanism. Within the larger context, particularly in what Peter Zinoman calls the “republican moment of scholarship,” Tùng’s perspective contributes to the breadth of alternative possibilities for a republican South Vietnam and eventually a noncommunist Vietnamese nation.

Now, having made a direct connection to republican ideals in Tùng’s, and even Thái’s, understanding of Vietnamese nationalism, it is also necessary to address the delicate balance between the particular and universal tropes of identity and freedom. Where particularity ends and universalism begins in the application of republicanism is a distinction fraught with tension and ambiguity. In the civilizing mission that underlay French colonization, for example, the effort to assimilate native populations into European cultures was premised on a belief of universalizing modernity and civilization. But this, as reforms soon indicated, violated the very liberties promised in the ideology behind republicanism. Put differently, Tùng’s emphasis on a Vietnamese identity in his idea of nationalism, despite being deeply influenced by values such as liberty and the basic human right to existence, also simultaneously thwarts the abstract universality of the Enlightenment ideology from which many of these republican ideals derive.

. . .

Although Tùng’s nationalism is structurally grounded on a European model, it is not without qualifications. The effort to explain what Vietnam is and to trace its history, as the opening in Le Vietnam et sa civilization (1952) tries to do with the question “Qu’est-ce que le Viet-Nam?,” prioritizes this ethnic identity and centers Tùng’s patriotism in these essays. He writes in January 1950 in the first essay of the series, “My writings, words and actions, from now on, will be dictated by the unique love for ‘Dai Viet.’”[xvii] It is this love for his country that gets him attention from many French readers, impressed by the way Tùng is able to represent Vietnam. For Tùng, then, what is most important is to strike a harmony between being a Vietnamese nation and being a nation in the world.

Nationalism and Republicanism in Trần Văn Tùng’s Literary Writings

Born in 1915 in Cần Thơ, Trần Văn Tùng grew up in a rural setting with access to a traditional education, because although his father was a farmer, his mother came from a mandarin’s family. As recorded in his memoir Souvenirs d’un campagnard annamite (1939), later published as Rêves d’un campagnard (1940, 1946), he admired the scholarship and respected position of a mandarin in the village. After being introduced to French culture at a young age, however, he left his rural family life to study in Hanoi. Such autobiographical elements are also incorporated into his novel Bach Yên, where the main character, Van, is tormented by the conflicts between the urban and rural setting, his family and his studies, his native Vietnamese culture and his adoration for French culture.

Despite being educated first in the Romanized Vietnamese script (quốc ngữ), Tùng’s writing career began predominantly in French and was informed thoroughly by French thought. This is reflected in his first two works, L’Ecole de France (1938) and Aventures intellectuelles (1939), the second of which won the Prix de la Langue Française for its extension of French thought outside France. Both works bring together a collection of excerpts from important French writers, especially known from the nineteenth and twentieth century, such as Stephane Mallarmé, Paul Valéry, and André Gide.

It was not until 1946 that Tùng’s political stances would become clear in his first and only novel, Bach Yên ou fille au coeur fidèle. The title is already suggestive of the female figure as a mouthpiece for patriotism and nationalism. This story of an ill-destined romance between two young lovers from different social milieux is a commentary on the way society views the new generation and, by extension, their potential to initiate change in society.

At the very center of the novel is a call to action to Vietnamese youth, a monologue in the protagonist’s voice, that claims the democratic ideals important to Tùng. More specifically, in eschewing tradition and the existing political structures, he instead highlights the importance of civic participation of youth to establish and maintain a common good, that is, a new Vietnam that would benefit all. Bach Yên, the desired modernized Vietnamese woman, becomes the confidante for the liberal thoughts of Van, the protagonist:

I cannot accept that our generation is ridiculed, scorned, and surveilled by these old traditionalists. Why does the torch of life remain eternally in the hands of young people? It’s our turn to speak out! To us, life! To us, hope, joy, happiness! To us, victory! We need another sky, another earth, a new society![xviii]

The novel also offers a social commentary on the role of women in society, supporting their access to education and greater freedom to make their own decisions. Considering Bach Yên’s literary role as an object of desire that only assists the protagonist’s expression of thoughts, however, Tùng’s position on gender equality remains largely underdeveloped.

. . .

As a writer, Tùng was able to wield support and publicity for his later political writings. From the beginning of his career, nearly all of his works include a paratextual element such as a preface or foreword from a prominent French figure, including Georges Lecomte, who was the president of the Académie Française in 1946, and René Cassin, a prominent human rights politician. Tùng was especially aware of the efficacy of casting his ideas for Vietnam far and wide. What is more is that he made this expansive communication clearly known, the paratextual matter in texts as evidence of this intention.

. . .

In examining this interaction between nation and world, particular and universal, it is important to consider the close connection between literature and politics for writers such as Tùng emerging after the 1930s. The preoccupation with French writers and French thought is a distinct quality of these Vietnamese writers of French expression. In the same way that the writer Phạm Văn Ký contemplated on sincerity through André Gide and the Symbolist poets and in the same way that Cung Giũ Nguyên drew on ideas of freedom from Descartes, Tùng’s preoccupation with liberty led him to linguistic, philosophical, and political reflections on Vietnam as a modern nation.

Because this cohort of writers was the first to be educated in Franco-indigenous schools and to have a choice in which language they could use to express themselves, the faculty of liberty is particularly meaningful. A faculty at the disposition of each individual, it represented a larger ability to choose and construct one’s fate independent of traditional or familial expectations. For centuries, the Vietnamese individual was occluded by the collective, liberty compromised for the respect of traditions, order, and status. As one of Tùng’s peers, Cung Giũ Nguyên, wrote in a 1954 essay, “Volontés d’existence,” this shift to valorizing the individual was not only modern, it was also necessary to widen Vietnamese perspectives and thresholds.

Nguyên’s essay, published in a collection with the same title, elaborates on the Vietnamese trajectory in understanding one’s existence, within the context of earlier institutions and limitations toward an individual, internal and philosophical experience of freedom. This quest for freedom begins by shifting the priority from worshiping a fixed past to imagining a future to construct. And to Nguyên, this conversion was only possible through contact with an Other that challenged the way these beliefs shaped the emerging generation’s understanding of the present: “The encounter with the West hastened the emergence of the individual, walled between these inadequate conceptions of social reality and human reality.”[xix] This might imply that colonialism was inevitable, or even justifiable, but it is more insightful to think about this encounter with the West as a process that prompted a conscious effort toward comprehension. Language becomes crucial, as does an openness to difference, otherwise the individual and his culture remain resistant to possible change.[xx]

The relationship that these writers have with the French language and literary scene therefore is extremely delicate: seeking to understand and be understood is integral to one’s will to exist and persist.[xxi] Tùng also directed a journal for the Democratic Party of Vietnam whose title was similar to that of Nguyên’s essay, La Volonté du Vietnam, as a vessel for communication. The journal included French- and English-language essays on the importance of a Vietnamese and French cooperation as well as items of general interest on Vietnamese culture and history. As was true for Nguyên, the implication for Tùng of this human will, or volonté, and the capacity to choose to do or not do something has a larger political significance.

. . .

With the advantage of his French connections, Tùng was able to frame the quest for liberty as a human concern in a way that relayed the Vietnamese cause to other arguments for human rights more generally. His rapport with René Cassin was particularly useful in this regard because the French lawyer was a key figure in establishing the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Droits de l’homme). Cassin’s preface to Le Viet-Nam face à son destin (1950) came two years after his work on drafting the declaration in 1948. Having worked on Jewish emancipation in the wake of World War II, Cassin saw a similar cause in the Vietnamese situation and thus found another case to internationalize human rights. He writes in the preface of Tùng’s text,

Do we not know from our own experience how much the learning or relearning of liberty is difficult, what pitfalls, what temptations must blow away or repulse the most modest citizens as the highest ranking leaders, if they want the new or renewed State to not be a simple façade behind which an oligarchy rules for its sole gain, but on the contrary a milieu of progress, appropriate to the fulfillment of individuals and of liberties?[xxiii]

Although Cassin is most likely speaking from his experience and observation of World War II events as well as his own investment in Jewish emancipation, his statement is also relevant for predicting the reality of the Vietnamese government. Tùng is framed here not so much as an ideal francophone writer or colonial pupil for others to follow in example but as an ally with a similar “human call for responsibility.”[xxiv] What one finds in Tùng’s text, according to Cassin, is not a “geographical manual or a political methodology” but multiple sources of patriotism that the author calls ‘a Vietnamese nationalism.’”

Most strikingly, the reader finds a close connection to France through “a national doctrine founded on principles of equality, justice and fraternity.”[xxv] Furthermore, this nationalism that was as universal in this sense as it was specific to Vietnam, “attached by all its natural fibers to the native land,” changes the way that Tùng’s advocacy for nationalism could be understood. It therefore spoke not only to the Vietnamese but also to other people of similar predicament, and the choice to include Cassin certainly opened Tùng to a larger readership even beyond literary intellectuals. In offering Tùng the legitimacy for his strand of nationalism, one imbued with humanistic ideas, this preface functions symbiotically, also giving Cassin a case to promote his agenda for human rights.

Legacies of Representation and Responsibility

Indeed, the role of the individual in the construction of country as a republican ideal is not new, especially to the Vietnamese: Phan Châu Trinh was one of the first Vietnamese to incorporate it into his reforms. Having formulated his antimonarchist position from the writings of East Asian reformists Liang Qichao, Kang Youwei, and Nakae Chomin, as well as their interpretation of France’s republicanism, Trinh saw the necessity of modernizing the country with the aid of the Third Republic. His essay “A New Vietnam Following the Franco-Vietnamese Alliance” addressed the self-strengthening of his people to form a national identity.

Despite the evils of colonialism, he saw assimilation as a necessary step in eliminating the monarchy and its ties to a feudal system that no longer worked for the Vietnamese people.[xxvi] Trinh was not alone to believe in the potential of republicanism in Vietnam; many of his peers in Paris, including Phan Văn Trường, Phan Bội Châu, and Hồ Chí Minh, tried to hold French Governor-General Sarraut and his administration accountable to their promises of civil liberties and representative politics. Such measures for representation could even be identified in the much antagonized Phạm Quỳnh and his efforts to push the limits for the freedom of expression and press and indigenous representation in the colonial assembly.

Following this legacy of a “New Vietnam” in which careful consideration of the circumstances were necessary before abolishing all foreign contact, Tùng’s appeals to the existing relationships with both the United States and France was an attempt to gain an advantage from those sources of aid. At the same time, Vietnam’s nation-building project had to begin from the inside, the Vietnamese needed to educate themselves about the nation, to learn to love and defend their country.[xxvii]

Likewise, Tùng believed in the individual’s contribution to the country, meant to be carried out through love for country and the responsibility to serve it.[xxviii] With Tùng’s cohort a generation later, beneficiaries of the schools and systems implemented by earlier reforms, the reiteration of republican values core to the construction of a nation becomes especially pertinent in the face of competing movements for independence.

What also marked this generation was their conviction that the emergence and development of Vietnamese youth was synonymous with that of the nation. In many ways, then, Tùng’s emphasis on youth intersected with mainstream narratives, particularly that of the communist party. But for Tùng, as it had been for Trinh, this relationship between youth and nation was directly tied to education and colonial reform. With more access to new forms of expression, liberation of the individual from traditional and familial constraints would lend itself to the symbolic liberation of the country. Vietnamese youth therefore became the object of many of his essays on nationalism. In 1950, he called for the need to

rely on the emerging generations, and its rich assemblage of intelligence, force, ardor, and will. More than any other country, Vietnam needs a healthy, courageous and audacious youth to raise its prestige and fulfill its historical mission. It is this youth who will carry the immortal touch of the country.[xxix]

Again in 1952, he dedicated his last chapter “La pensée guide l’action” to la nouvelle jeunesse du Viet-Nam. The same message resonates:

What life do you want to live, a life of vice, of debauchery? . . . A life that is easy and monotonous? . . . May your life, oh valiant brother, be one in search for an order, in pursuit of an ideal, the production of a work, the accomplishment of a mission![xxx]

Contrary to the myth that any movement outside the revolution was subject to idleness and indulgence, young nationalists were charged with the reconstruction of their country. Tùng politicized the social category of youth by attaching them to political and social change but not violent revolution. Like his law of perpetual becoming, “a young and modern nation does not know to be something rigid, immobile . . . it is something that lives, quivers, changes, transforms, grows, renews, embellishes itself, improves itself constantly.”[xxxi]

What distinguishes this youth from others is the encouragement for discovery and curiosity, for though their responsibility is clear, they are also sincere about their efforts to reconcile their confusion with their expected national duty. This kind of negotiation is the only way that a nation can evade the risk of extinction or disappearance, for a nation needs to continuously return to this fountain of youth and evolution. As a member of this new generation educated in French himself, Tùng in his trajectory from scholar to diplomat illustrates how much these literary and philosophical possibilities influenced his political ideas.

Working with American Models of Democracy

Despite the broad gestures toward representation, Tùng’s essays and general program were still addressed to an intellectual elite. In other words, this was a major flaw in Tùng’s idea of representation, because although education became more widespread, it was still not accessible to all Vietnamese. This elite bore the task of a “pedagogical mission,” to “shape the youth, educate the people, bring them toward progress,” and it is to this elite that the “highest functions of the state must be granted.”[xxxii] In May 1955, this elite took the official form of the Democratic Party of Vietnam.

Founded by Nguyễn Thái Bình, a Vietnamese dissident residing in Paris, with Trần Văn Tùng as the secretary general, the Democratic Party of Vietnam positioned itself as a viable third solution, an alternative to the binary choice between Diệm or a communist government. A brief summary of the party is laid out in Nguyễn Thái Bình’s 1962 publication Vietnam: The Problem and the Solution. For the American public, Bình’s presentation of the Democratic Party would be particularly familiar, citing the age-old democracy trifecta of a government “for the people, by the people, and of the people.” This quote, known to most from its mention in Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in 1863, is also a direct reference to the Declaration of Independence, even though the official document itself does not contain these words verbatim.

. . .

Although Bình never uses the term “civil war” explicitly, both he and Trần Văn Tùng are clear about the current war being an internal one, only to be resolved between the Vietnamese themselves. The threat was not only foreign ideology but also the loss of democracy more generally under Diệm’s government. In fact, to Bình and Tùng, the main reason for the success of the communist-led National Liberation Front in the South was not because the people of the South supported communism but instead because the organization presented its ideology as the only alternative to a corrupt and totalitarian society.[xxxiii] In other words, the current Diệm administration, which Bình and Tùng believed to be motivated by familial, private, and foreign interests rather than by those of the people, only exacerbated the tendency of the people to turn to communism for relief.

As an exile and expatriate in France, Tùng was able to write with more freedom about Vietnam even though he was not directly in touch with the everyday happenings or political constituents in the country. He was openly critical of the Ngô Đình Diệm administration and was even reported in September 1963 to urge for a united anti-Diệm stand among the exile community in Paris.[xxxiv] Like many Vietnamese, however, he had initially trusted in Diệm to take on an effective fight against communism.

In 1952, when Tùng came to the United States for the Far East Conference in New York City, he visited Diệm at the Maryknoll Seminary in Ossining, New York, to advise him to return to Vietnam to fight the communist cause. Some would later criticize Tùng for having made this trip in the first place. Within a few years though, Tùng became disillusioned by Diệm’s oppressive policies. In fact, Diệm’s ban of opposition parties in Vietnam violated what Tùng valued to be an important democratic quality: the freedom to express differing, even revolutionary ideas. Many Vietnamese dissidents were put in prison or sought refuge abroad; they organized themselves in Paris and circulated nationalist, anti-Diệm publications among themselves.[xxxv]

Bình and Tùng’s anti-Diệm, anticommunist, antifeudal, and antineutralist positions were broadcast in various news articles and publications, but also reiterated in letters addressed to the John F. Kennedy administration between 1961 and 1963. In July 1961, Bình wrote to presidential adviser Walt Rostow regarding the corruption of Diệm administration, saying, “Diệm is anti-communist only because he is anti-anything that opposes him.” He asked the United States to send an investigation committee to track down where American funds were being funneled because the Vietnamese people were surely not seeing any of them.[xxxvi] He sent the exact same letter to Arthur Schlesinger, the special assistant to the president, dated the same day and likely to National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy as well.[xxxvii]

Bình continued to write to Rostow despite little evidence that Rostow ever returned his letters. In October that year, Bình sent him a letter outlining a clear alternative to Diệm’s government, proposing a provisional government made up of “younger field-grade officers of the South Vietnamese Army” and a subsequent transition to a civilian government afterward. His plan also suggested continued American aid, but to gradually shift that aid toward economic and cultural development.[xxxviii] Bình sent a copy of The Problem and the Solution to White House Press Secretary Pierre Salinger in December that year and to Kennedy’s appointments secretary Kenneth O’Donnell in February the following year.[xxxix] Correspondences between Bình and the American personnel seem to have tapered off by the end of 1962.

Like Bình, Tùng also actively wrote to the Kennedy administration and even tried to seek meetings with them during his visit to Washington in March 1962. A week before his trip, on March 7, he enclosed in his letter to Salinger a copy of the speech he planned to give during the visit.[xl] The speech made a point of “linking American and Vietnamese destinies,” which aligned the Vietnamese cause to the American principles of freedom and democracy. “But surely,” Tùng wrote, “there must be a limit beyond which a great nation cannot go without denying its own greatness and betraying its principles, those principles and ideals from which it has drawn its strength and its glory.” Also important was Tùng’s commentary of Vietnamese morale, for without a proper government and a reason to save a nationalist Vietnam, “the Vietnamese people were disheartened and discouraged.”

These letters may have swayed some Americans to consider taking them seriously because in one memorandum from Michael Forrestal to Ambassador Averell Harriman in February 1963, Forrestal suggested the possibility of expanding contacts between US personnel in Saigon and noncommunist elements of the Vietnamese opposition. It is unclear from this note which noncommunist elements he meant, though if he was referring to the Parisian dissidents, actions on such measures were never taken. When Tùng wrote to Schlesinger in October 1963, Schlesinger forwarded both his letters to Forrestal. In response a week later, on October 24, Forrestal curiously advised Schlesinger that “at this stage,” it would be best to “keep our traffic pretty bland.”[xli]

With the help of Bundy and Schlesinger, Bình and Tùng’s letters were circulated within the administration, though the Vietnamese men only ever received tepid responses to acknowledge their reception. A few considerations may explain this reaction. As Sean Wilentz suggests, President Kennedy’s Cold War realism did not make room for Vietnamese perspectives such as the Democratic Party of Vietnam, which like Schlesinger seemed to support a middle ground alternative between an anticommunist and anti-authoritarian government.[xlii] This meant that despite how “unsavory” a regime was deemed, US foreign policy would back whichever one it perceived to be most stable and viable to beat back communism.

. . .

Such developments did not hinder Tùng from continuing to advocate for his party’s mission, and the elimination of Diệm and Nhu in 1963 only further prompted them to concretize their plan for rebuilding Vietnam as a democratic nation. In January the following year, a few months after Diệm’s death, Tùng published with the Democratic Party of Vietnam a report titled the “Fundamental Conditions for Victory in Vietnam.” Arguably one of the more concrete political documents Tùng had written, the report consolidates the various ideas that Bình and Tùng had communicated to the American public over the previous few years outlining what Tùng called a Nationalist Program for Unity and Progress that touched on economic and agrarian reform, reorganization of the military, and reforms to foreign policy.

He outlined a revision of the “political physiognomy” that would consist of a president, three vice presidents for each region, and a National Congress that would balance executive power. Military reform would purge the army of corrupt elements and place civilian control in the hands of intellectual elites. Most notably, he saw the importance of building social infrastructure, including hospitals, schools, housing developments, modern universities, railways, as early twentieth-century intellectual Phan Châu Trinh had always envisioned. Although the details to realizing these reforms were not yet outlined, Tùng’s guiding principle was to “restore to each Vietnamese citizen his fundamental rights as a free man in an independent society and to assure protection of these rights under due process of law.”[xlv]

. . .

After this last 1964 publication, news regarding Tùng or his Democratic Party of Vietnam is strikingly sparse. During this period of active public and political intervention, however, what we can learn through an examination of Tùng’s nationalism—its foundation on liberty, youth, and democracy—is the extent to which the Vietnamese were committed to their nation-building project, even despite the American disregard for their plans. In a speech to the American press in Paris, Tùng expressed his frustration in this regard by asking, “Does America really have a conscience . . . ? Where is the conscience of the Free World? Is it dead or is it only sleeping?”[xlvi]

. . .

In the last decade, nationalism as an ideology has taken a particularly malignant turn in response to the erasure of borders and the increasing flow of people and ideas. “New nationalism” in this sense is used as a basis for anti-immigration, nativist positions that privilege homogeneity in the guise of a collective welfare. But new nationalism has not always implied such a separatist perspective. In an earlier, rather famous evocation of this idea, American President Theodore Roosevelt seemed to harp on the opposite message.

His speech in Osawatomie, Kansas, in 1910 called for a collective mindset that would protect human welfare and property rights. When Barack Obama evoked the idea again a century later in 2011, he reiterated its strong reminder of America’s democratic foundations, in which each individual is entitled to work and earn the fruit of that labor. The capacity to partake in the economy in this way is fundamental to the liberties that the Declaration of Independence guaranteed.

It is curious then that in his idea of a nation, Tùng had already evoked similar ideas in the first installment of his essay series:

The working class will reassume an important role in society!

To each, his work! To each man’s work, his compensation!

All Vietnamese who work will be nourished, clothed and decently sheltered.

Education and civic rights will be available to everyone . . .

Our first concern is to make of every citizen a man,

and to give him all the changes of becoming a free man,

taking into account his faculties and potential.[xlvii]

The commitment to recognizing the working class and the restoration of a meritocratic system where work is repaid by an appropriate compensation is imperative in a democratic nation. Whether Tùng was inspired by American or French democratic ideals seems less important than that they were closely aligned, and continued to be, even in the midst of the Vietnamese dilemma. Perhaps then, Tùng’s early ideas of nationalism in the 1950s anticipated the later desire for its redefinition in light of societal transformations under the communist regime as well as Diệm’s administration. It is as Vũ Văn Thái aptly writes in 1966:

If all the turbulent developments of the present can be channeled into

a concept which would maintain harmony between the basic values of

Vietnamese identity and the need for representative government and a just society,

then the evidence will have been provided that the alternative to

communism in the emerging nations does exist.[xlviii]

Notes:

Epigraph. Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin (Paris: Editions de la Belle Page, 1950), ##.

[i] Trần Văn Tùng, letter to the editor, New York Times, October 24, 1953.

[ii] Tùng also wrote to the New York Times in August and September 1955 and November 1961 and appeared in the Buffalo Evening News in September 1962. Additionally, the Washington Post reported on his visit to Washington in March 1962.

[iii] See Henry Hazlett, “L’Annam vu par Trần Văn Tùng” (masters’ thesis, University of Washington, 1950), 72; and Karl Britto, Disorientation: France, Vietnam, and the Ambivalence of Interculturality (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004), 28.

[iv] François Guillemot, “Penser le nationalisme révolutionnaire au Viêt Nam: identités politiques et itinéraires singuliers à la recherche d’une hypothétique,” Moussons: recherches en sciences humaines sur l’Asie du Sud-Est 13–14 (2009): 147–184, especially 154.

[v] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin (Paris: Editions de la Belle Page, 1950), ix.

[vi] See in particular Tuong Vu, “Triumphs or Tragedies: A New Perspective on the Vietnamese Revolution,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 45, no. 2 (2014): 236–257; Nu-Anh Tran, “Contested Identities: Nationalism in the Republic of Vietnam (1954–1963)” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2013); and Guillemot’s “Penser le nationalisme.”

[vii] Consider the borderless approach to nationalism in Benedict Anderson’s concept of imagined communities, Ernest Gellner’s argument for identical ethnic and political boundaries, and Nu-Anh Tran’s argument that the state consolidates the legitimacy around nationalism. See Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1991); Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism: New Perspectives on the Past (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983); and Tran, “Contested Identities.”

[viii] Tran, “Contested Identities,” 14.

[ix] Vũ Văn Thái, “Vietnamese Nationalism under Challenge,” Vietnam Perspectives 2, no. 2 (1966): 3–12, especially 3.

[x] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin, 9.

[xi] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam au combat: nationalisme contre communisme (Paris: Editions de la Belle Page, 1951), 14.

[xii] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam au combat, 30.

[xiii] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin, 9, 19, 32; Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam au combat, 16–17.

[xiv] Christopher Goscha, “Aux origines du républicanisme vietnamien: circulations mondiales et connexions colonials,” Vingtième siècle 131 (2016): 17–35, especially 33.

[xv] Terry Eagleton, “Nationalism: Irony and Commitment,” in Nationalism, Colonialism and Literature (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990), 23.

[xvi] Eagleton, “Nationalism: Irony and Commitment,” 30.

[xvii] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin, xxvi.

[xviii] Trần Văn Tùng, Bach Yên ou fille au coeur fidèle (Paris: J. Susse, 1946), 116.

[xix] Cung Giũ Nguyên, Volontés d’existence (Saigon: France-Asie, 1954), 7.

[xx] Cung Giũ Nguyên, Volontés d’existence, 40.

[xxi] Paratextual material, including prefaces and introductions to many Vietnamese Francophone works, can be read in a new political light in their effort to be widely read and understood. For example, see Cung Giũ Nguyên, “Liminaire,” introduction to Volontés d’existence; Đào Đăng Vỹ, preface to L’Annam qui nait (Hue: Imprimerie du Mirador, 1938); and even Phạm Quỳnh’s opening remarks in his Paris Conferences, Quelques conférences à Paris (Hanoi: Imprimerie de Le Van Phuc, 1923).

[xxii] Cung Giũ Nguyên, Volontés d’existence, 73.

[xxiii] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin, xii.

[xxiv] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin, xiii.

[xxv] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin, xii.

[xxvi] Goscha, “Aux origines du républicanisme vietnamien,” 33.

[xxvii] Vĩnh Sính, Phan Châu Trinh and His Political Writings (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009).

[xxviii] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-nam et sa civilisation (Paris: Editions de la Belle Page, 1952), 109.

[xxix] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin, 51

[xxx] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-nam et sa civilisation, 97–98.

[xxxi] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin, 8.

[xxxii] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin, 26.

[xxxiii] Nguyễn Thái Bình, The Problem and a Solution (Paris: Viet-Nam Democratic Party, 1962), 103; Trần Văn Tùng, The Fundamental Conditions for Victory (no publisher, 1964), 2.

[xxxiv] Peter Grose, “Vietnamese Exile Leader in Paris urges Anti-Diệm Stand,” New York Times, September 11, 1963.

[xxxv] Two such publications included the “confidential bulletin” Sword of Free Vietnam and the “White Paper on Ngô Đình Diệm’s regime,” a collection released in 1961 by the Free Democratic Party of Vietnam Overseas Organization that included previously published articles and opinion pieces critical of Diệm. Copies of these publications were also sent to the Kennedy administration. See various copies of the publications in White House Central Subject Files, Box 75, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library (Kennedy Library).

[xxxvi] Nguyễn Thái Bình to Rostow, July 18, 1961, White House Central Subject Files, Box 75, Folder 1, Kennedy Library.

[xxxvii] Nguyễn Thái Bình to Schlesinger, July 18, 1961, Arthur Schlesinger Private Papers, Box WH-19, Folder 10, Kennedy Library; Bundy to Battle, July 24, 1961, White House Central Subject Files, Box 71, Folder 1, Kennedy Library.

[xxxviii] Nguyễn Thái Bình to Rostow, October 23, 1961, White House Central Subject Files, Box 75, Folder 1, Kennedy Library.

[xxxix] Nguyễn Thái Bình to Salinger, December 1961; Nguyễn Thái Bình to O’Donnell, February 20, 1962, both in White House Central Subject Files, Box 75, Folder 2, Kennedy Library.

[xl] Trần Văn Tùng to Salinger, White House Central Subject Files, Box 75, Folder 2, Kennedy Library.

[xli] Forrestal to Schlesinger, October 24, 1963, Arthur Schlesinger Private Papers, Box WH-19, Folder 10, Kennedy Library.

[xlii] Sean Wilentz, foreword to The Politics of Hope and The Bitter Heritage: American Liberalism in the 1960s, by Arthur Schlesinger (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), xxiv.

[xliii] One letter to the editor expressed reservations regarding Tùng’s announcement of his party in the New York Times. The letter writer considered it suspicious that Tùng “does not say who his colleagues are, what their number, nor explain the curious fact that it emanates from Paris and not Saigon.” See Christopher Emmett, letter to the editor, New York Times, August 23, 1955.

[xliv] Although Schlesinger described the Paris-based activists as “disaffected intellectuals” who still made a great deal of sense, American officials deemed it contrary to national interests to respond to the dissidents’ letters. For Schlesinger’s view of the Vietnamese dissidents, see Schlesinger to Bundy, November 15, 1961, Arthur Schlesinger Private Papers, Box WH-19, Folder 10. For reluctance to reply to their letters, see Stoessel (on behalf of Dungan) to Goodpastor, January 20, 1961, White House Central Subject Files, Box 75, Folder 1, Kennedy Library.

[xlv] Trần Văn Tùng, Fundamental Conditions for Victory, 7.

[xlvi] For the speech, see Trần Văn Tùng to Schlesinger, October 15, 1963, Arthur Schlesinger Private Papers, Box WH-19, Folder 10, Kennedy Library.

[xlvii] Trần Văn Tùng, Le Viet-Nam face à son destin, 51.

[xlviii] Vũ Văn Thái, “Vietnamese Nationalism under Challenge,” 12.

You may like

-

In search of what I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải (Part 3)

-

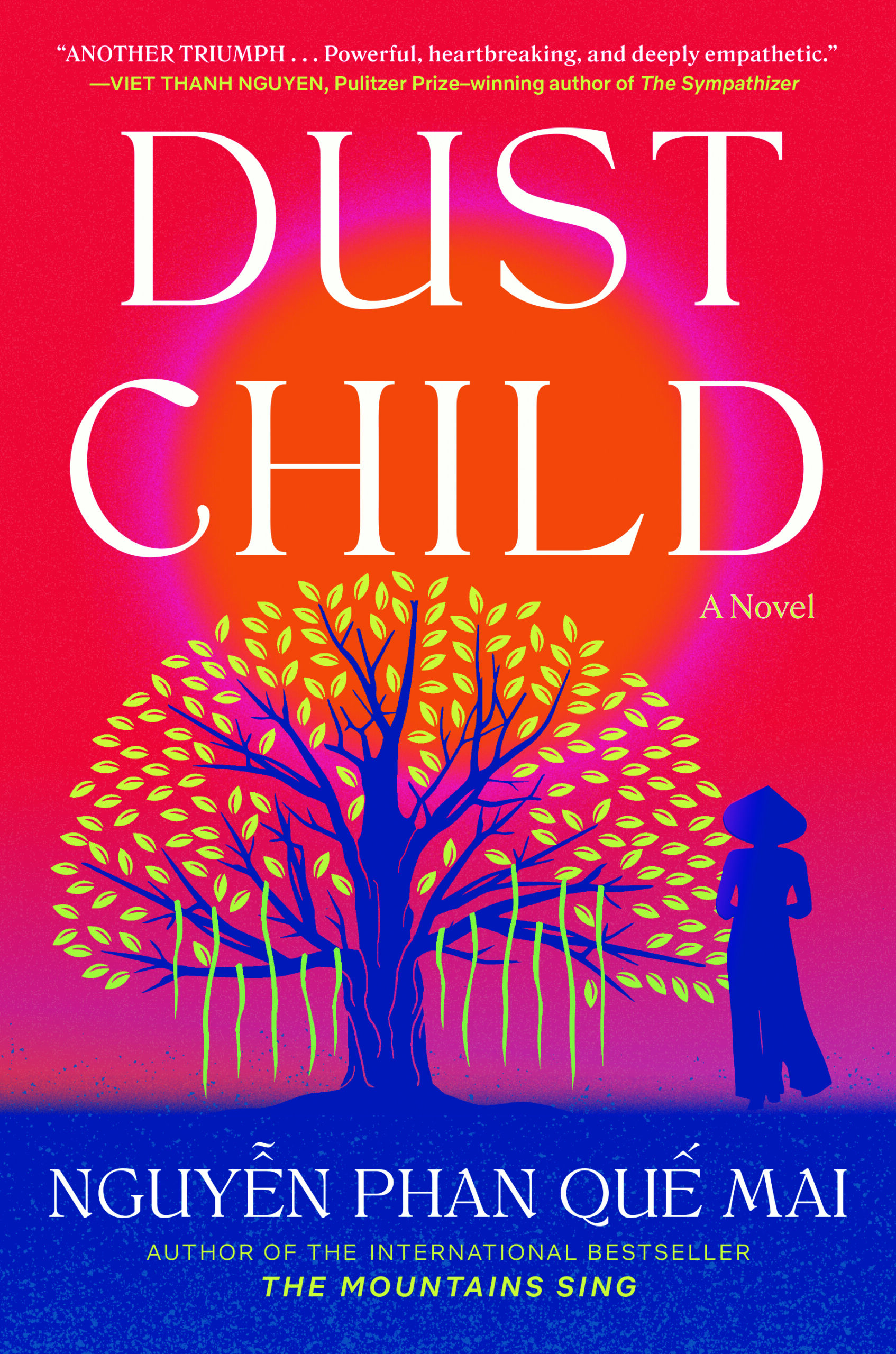

Dust Child (Book Review)

-

In search of what I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải

-

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 15 – Hanoi at Midnight

-

Sigh, Gone and Saigon: An Interview with Artist & Author Phuc Tran

-

A Tribute to Thanh Tâm Tuyền’s Lệ Đá Xanh — Dương Như Nguyện’s Crying Green Jade

Reflections on New Era of National Rise by Vietnam General Secretary Tô Lâm

Of Space & Place: On the Nationalism(s) of Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s “Our Ghosts Live in the Future”

Postwar Music In Vietnam And The Diaspora

Translation: The Decision in 2013 of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Certain Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform

Thủ Đức Demonstration High School: A Modern Educational Policy and Teaching Method of the Republic of Vietnam

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years agoRethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

-

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years agoDeporting Vietnamese Refugees: Politics and Policy from Bush to Biden (Part 1)