After 1975

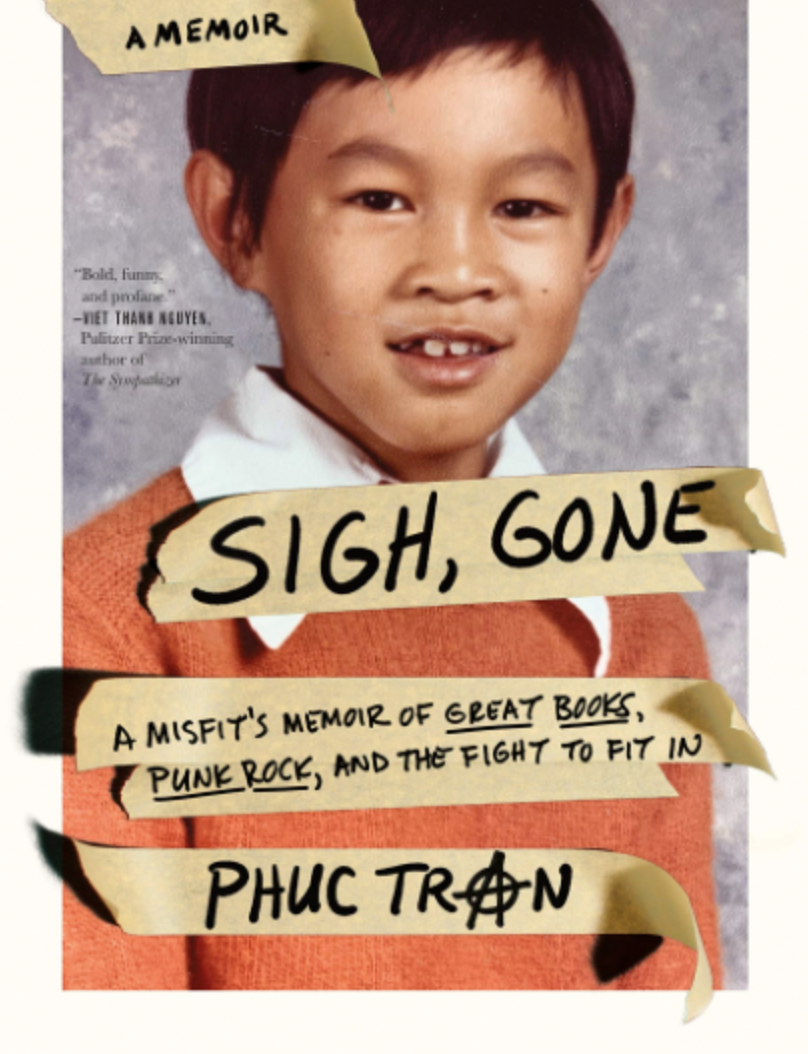

Sigh, Gone and Saigon: An Interview with Artist & Author Phuc Tran

Published on

By

Phuc Tran

Editor’s Note: The transcript of this interview was edited for readability, and some quotes have been altered to better capture the intent of the interviewee. I have abbreviated my name (Vinh Pham) to VP and Phuc Tran to PT. To learn more about Phuc Tran or to order his book, please visit his website here.

Author, tattoo artist, Latin teacher, husband, father, and all-around funny guy, Phuc Tran is a man of many sides. His 2020 memoir, Sigh, Gone: A Misfit’s Memoir of Great Books, Punk Rock, and the Fight to Fit In, is a shining example of how humor may open the door to many great conversations about class difference, cultural identity, and teenage angst. As one of my personal favorite entries within the cannon of Vietnamese-American memoirs, Tran’s work is a chimera of sorts — it is cool in conception on the one hand, and deeply terrifying for Vietnamese parents on the other. To me, this terror comes not from its occasional playfulness with obscenities, which is a breath of fresh air for those of us accustomed to a genre inundated with tears and trauma, but by way of Tran’s unwavering honesty about his bumpy childhood and his evolving relationship with his parents. This is not a level of honesty afforded to everyone, and Tran knows this. Among the many things discussed, we also talked about growing up as Vietnamese-American, writing as a Viet person, and raising children. Tran is an open book, and someone who wants to be seen a full human.

When asked how he felt about his parents’ reception of his work, his response was, “unencumbered,” an answer typically not heard in a community whose literature is often the vehicle to intergenerational healing or trying to address issues of the war (nodding to Ocean Vuong). Maybe this is a good thing, I thought. What would the Vietnamese-American literary space look like, when those who want to speak out feel no fear or shame about their experience? What if the “model minority,” does not give two cents about being a model for anyone at all? These are some of the questions that circulated in my mind as I sat down with the author. Now a father himself, and far from his hometown of Carlisle, PA, Tran lives with his family in Maine. The following is a condensed version of a recent interview I conducted with the author:

VP: I actually picked up your book at a friend’s house because I saw your name on the book and said, “oh, that’s a Vietnamese name,” and I saw on your website that Viet Thanh Nguyen said “The United States was already a better country because Phuc Tran refused to change his name,” so I wanted to ask you if you feel like the jokes about your name have subsided over the years?

PT: Oh yeah, I think so, yes. I think mainstream American culture has just been more exposed to non-Anglo names. I also just don’t hear it anymore, because the context in which you hear it is just kids being shit heads and once I was out of high school I definitely didn’t hear a lot of it in college. I guess I would say I still hear it once or twice a year because someone would make a joke, but it just doesn’t bother me anymore because it is more of reflection of their stupidity.

I just don’t have the bandwidth to take on their bullshit. But I hear it less, for sure. Again, hearing it less doesn’t mean it isn’t happening. It just means I am in a context where I am less likely to hear it. I love a good joke, but it is just lazy. I doesn’t bother me anymore though because I’ve had therapy [chuckles].

VP: You have “author, educator, classicist, and tattooer” on your website, which obviously is an eclectic list of occupations, and you also quoted Walt Whitman saying “I contradict myself, I contain multitudes” and I do feel that is generally true. I think on most days we have all of that in us, but do you feel on some days you wear one hat more than others?

PT: I think it depends on the context. Like when I am in the classroom, I am definitely a Latin teacher, you know slash educator person. My tattooing doesn’t really enter the classroom. My being Vietnamese-American, for example, I can’t hide it, but it also has nothing to do with teaching Latin to high school kids. And that is not to downplay it.

I mean, for some students I might be the only teacher of color that they’ve ever had up to that point or maybe even ever, I don’t know. I don’t know about you, Vinh, but I’ve never had a teacher of color, like ever. I’ve never had a black or brown teacher. I don’t know what that says about our educational system. It is also generational. Maybe nowadays it might be different. Have you had black or brown teachers?

VP: I had quite a few, but I also grew up in South Florida.

PT: Yeah, so when you’re talking about identity, it is a social contract, right? So I may go into a situation and be like, I’m a Latin teacher, but my students are like “here is a Vietnamese guy.” So we have to kind of negotiate and talk about how does their perception or first impression of me as a Vietnamese man play out in the classroom, or how do they see me et cetera…Whereas I am just here to teach you Latin. That is true any time when you are in community with other people. Meaning that you may think you are awesome and then the whole group decides that you are a shithead, then it just becomes an interplay of power and group dynamics. So I don’t want to say that it is meaningless how I identify myself.

Like, I might not want to wear the Vietnamese hat, but then I go into the grocery store and then I have this interaction and go “oh, wait a second, let me put on the Vietnamese hat.” Or if all my tattoos are showing—in New York City this happens all the time, and this was the 90s so tattoos were a little bit sketchier to people, but if I had a short sleeve on in the subway, no one would sit next to me on the subway.

But If I was coming from my Latin teaching job and I had long sleeves and a tie on, people would sit next to me. That was observational and always funny to think about. It’s always helpful for me to think about how people perceive me and how I think of myself. It makes me think of Dubois and double consciousness, which when you’re in a marginalized community, you are always thinking about how others are perceiving you.

VP: It is really important we see ourselves in relation to how other see us, so my follow-up to that is: how do you think your parent’s vision of you have changed?

PT: [big laugh] Wait, do you mean like who my parents think I am and who I actually am?

VP: I guess in the sense that Vietnamese parents, at least from my own experience, they never believe you want to do something until you prove it to them and say “hey, this is the thing that I am doing.” Then you have to take it to a certain level and it becomes valid, a stamp of approval, once it reaches a certain caliber.

PT: [nods in agreement] And it is usually financial or success right? Like, you’re famous or you made a lot of money, whatever whatever? Yeah.

VP: Yes, exactly that. So do you feel like their vision has changed about what you wanted to do? Because, at least from my imagination, most Vietnamese parents are not jumping up for joy when their son says, “I want to be a tattoo artist,” but if you are a sought-out tattoo artists, then it becomes something considerably different. I feel like that is always a part of the measure for them.

PT: Yeah, I think my parents loved me in whatever way they could and supported me in whatever way they could, maybe not in the way I wanted them to, but I also think they were like “he’s just going to do what he’s going to do.” I think they kind of gave up on trying to do more. I am also not in a relationship with them. I mean, I am not estranged from them, but I am also not looking for approval from them. We’re not supper close or anything like that.

I mean, we have a family text thread. They send me li xi for Tet and stuff like that [chuckles] because they think I am broke. They have no idea what I do for work so they’re like “here is some money, cause we don’t actually know what you do for a job.” They were really excited I went to college.

I think there was a point where they thought I was going to be dead or in a gang or do drugs. Then I went to college and studied Latin. Then I went to grad school and my dad was like “oh sweet, he’s gonna get a PhD,” but then I didn’t get a PhD. So I think my parents are always looking for bragging rights with their Viet friends, which is weird.

I don’t know if that exists in other cultures, but in Viet culture, I think it is extra strong where you just want to flex on other Viet people with your kid’s success. That’s more of my brother. I always joke that my parents get to brag that they have a lawyer and an engineer in the family, it just happens that my brother is both of those things. But yeah, I don’t know, I guess my parents aren’t like, “we’re really proud that you’re a Latin teacher.”

Even when I wrote my book, they were very helpful. They gave me a lot of information and I did a lot of research to make the timeline correct. They didn’t read an advanced copy and they thought it was going to be this lucky immigrant story making good in America sort of thing and, you know, it was just about how complicated my relationship was with them and with my town. So when the book came out, my dad hadn’t read it.

He just straight up bought one hundred copies to give to his friends, and he lives in Orange country, then he reads the book and was like “oh, fuck.” Then he just left them all in his garage, so he’s got a hundred copies of my book that he won’t give out to anybody because, you know [laughs]. It’s classic.

VP: I want to keep talking about this, did he say at what point he decided that he can’t send this book to people?

PT: I don’t know. You would think if your kid did something like write a book, you would acknowledge it and say, “hey, good job” or “congrats.” That didn’t happen. I didn’t hear from them for six months, so finally in a family text thread, I asked if they read the book. My dad texted back saying, “yes, it was very painful.” That was all they had to say about it… I saw them recently this past year when we flew out to California, and as we were all together someone asked my dad what he thought of my book and he said, “I didn’t like it, but it is his story to tell.” I was like, that is super mature. That is a complicated thing for a Vietnamese person of his generation to express. I think the book is just too raw and spicy for him.

VP: When you were writing, were there any particular moments that made you think, “oh this is too spicy”?

PT: No. I think…No. I think it is partly because of my relationship with them. Someone asked me “are your parents dead? Because you write about them like they are dead and will never read the book.” I just said, “oh no, they’re alive.” For better or for worse, I’m unencumbered from any kind of approval from them. I also recognize it’s my story to tell and this is a memoir, so it is how I experienced it.

There is a funny story: a few years back when my parents visited my family in Maine, this is after the kids had already gone to bed, and my dad said, “you know what the issue with Michelle Obama’s book is?” So ask him what, and he said that it “deals too much with her feelings. She doesn’t focus on facts, and that’s going to be the problem with your book.” I was like, wow, ok. My wife looked at each other in surprise. To him, if you were to write a story, you just deal with the facts. Who cares about your feelings? I do think it is cultural.

Being raised in American culture, you do have to recognize, if this is how you feel in a certain situation, then they determine your “reality” –They also determine how you interpret that reality and how things affect or have an impact on you. Culturally, I think that is really difficult to navigate. Even the whole culture of therapy and self-help, I think that is just now becoming a thing with Vietnamese-Americans.

The mental health part is certainly not something that is talked about much, if at all. I don’t know what your situation is like, but with our parents’ generation, I mean, they saw some shit. They have to find a way to deal with that in a healthy way besides drinking Hennessy and beating their kids.

VP: I think karaoke is very therapeutic, I don’t know what you are talking about…

PT: [big laugh] Yes! For sure.

VP: So this is interesting to me, I don’t know about every other contexts, but at least with my own family I recognize that we probably suffer from a lot of trauma that is not handled in a professional way. I do think there is mistrust, which is not exclusive to Vietnamese people, but the older generation, and especially immigrants, really don’t recognize certain things as trauma. I remember being on train ride with my mother in Paris heading back to the airport, and I just mentioned that a Vietnamese historian friend of mine is writing a book, and her immediate response was, “they can’t know what happened. How would they have known?” To her, people are always lying in history books.

So, going back to your father, I feel like with a certain generation, there is a reliance on history because they feel like they have been robbed of a history. Of course, I told her that as a scholar I can’t always have first-hand experience of a thing, and maybe that is even better because I won’t be clouded by personal experience. Also, with that criteria of first-hand experience, I also would not be able to work on anything prior to my existence. Then I just asked her, “well, what do we do about history, mom? Someone has to write it, right?” So then she just broke down on this train, in front of everyone.

In Vietnamese-American literature, there is a lot of pain after the war, and some of the novels are very much historical fiction. We avoided direct biographies for a while because it was raw. But now it seems there is room again for the memoir, where we touch more on personal history—with your own parents, when you write about these experiences, do you feel like there is a way to move beyond the memoir form and still retain a sense of history?

PT: I think that is so interesting, I am trying to think of other diasporic narratives and how those are treated. The first ones that I think of are of the Jewish diaspora and black American narratives—your phrasing is “to move beyond the memoir,” so what would it look like in those narratives? I mean, I am sure that it will happen, and maybe it will happen with Vietnamese-American narratives, as well. I think you will also need a critical mass of narratives and interest.

I mean, academia is adjacent to capitalism, so it boils down to: who wants to read this shit, and if there is interest then there will be things written, podcasts, etc.…what do you think? I would look at other diasporic communities and see what they do. When I think of the Jewish diaspora, for example, they have had such a strong tradition of community that they have maintained a narrative and a way to storytelling. And when I think of the black American community, they at least have a situatedness and a claim to space, but I don’t know what will happen with Vietnamese-American narratives.

I am also curious about expanding the American narrative, so it can include the Vietnamese narrative, rather than contract itself. I would love to see it expand and be more exclusive. Especially in a climate where it feels like everyone is just trying to claim their piece of land, I would love to see us expand what the definition of the American narrative means, and see the Vietnamese narrative as a part of that, instead of just being adjacent to it. What’s your answer to that question, Vinh? How do we move beyond the memoir and what does that look like?

VP: I am not sure I have an answer to that, I really like reading memoirs. What I was most drawn to in your book was the rawness. There was an affinity and representation for me. There is one section where you talked about your first girlfriend, and you were like “I gotta show up for every guy who has to be in my situation.” To me, it was really speaking to the time in the Vietnamese diaspora where there was traction in the literary scene, but still just not enough where you felt like you had to be “that” Asian boyfriend.

In the 90s, when I came to the United States, we were still very much in the multiculturalist era where there was always an Asian character, always part of the bricolage of colorful characters, but they never have their own thing, or if they do, it’s Joy Luck Club. So I really appreciated reading something, where you didn’t play the “no, I won’t be the model citizen, but I will be a damn good student.”

PT: [laughs] Well I really did get that scholarship to get out of my town. Well, I think Ocean Vuong’s novel does something similar in that he is not trying to plow the same fields as others in the Vietnamese-American narrative. There is a lot of complexity. I think his queerness is front and center from this and his “Vietnameseness” is a ligature that adds to this complexity. I didn’t read his book until after I finish my book, just because I wanted to write the book I was going to write.

My process is so fragile and permeable that I didn’t want it in my head. But his writing is just gorgeous and incredible and I love that there is this beginning for a wide array of voices that expresses what it means to be Vietnamese-American. It’s the expansion of Americaness in general. I mean, a lot of these questions are dependent on academia, the market, publishing, and things we don’t really have control over.

It was like when Crazy Rich Asians came out and it did well at the box office and people were like, “oh shit, American audiences want to watch Asians?” So, you know, its market driven, which makes me feel cynical. Like, at no point was anyone like, we should do this because it is the right thing and it is important. No, it’s because it is going to make money. Is that true in academia too? I have no idea.

VP: I feel like there are some strands of similarities there. I did feel funny about the American discourse on representation for Asians, because Asia has a huge film market. So to me, the argument was coming out of Asian Americans that grew up in the United States who wanted to grow up in proximity to whiteness, wanting to see themselves through the specter of whiteness, as opposed to just looking at, say, Hong Kong or Japan, or even Korea. I also found it funny that the film just took the genre that is typically white dominated, upper-middle class, and running with it saying, “this is the acceptable lens through which “we” ought to see ourselves, in a palatable way. It was very Pei Wei cinema.

PT: Wait, what do you mean by Pei Wei?

VP: Like, Chinese-American food.

PT: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah.

VP: Which, I don’t think is good or bad. I do think everything should be available, these are cultural products. But I liked your cynicism, because I remembered when I pitched my dissertation about French Vietnam to a would-have-been advisor, they just said, “no one is going to buy this book.

PT: [laughs] I think Viet(Thanh Nguyen) tackles the whole Franco-Viet angle in The Committed, it’s on my shelf. It’s also a numbers game. Because to what extent is representation appropriate vis-à-vis how prevalent we are in American Society? Because we are like 6% of the population. So is that what you want to see on the screen, or are you trying to just see something not racist? So I think there is a pendulum swing now the other way.

Someone did a study about fiction writing from the 1950s till now and it is 98% of them are written by white dudes, you should double check me on this. So, now there is a pendulum of books moving in the other direction, which feels like an overcorrection, but I am fine with it, and it will also probably swing back the other way soon.

I do like your analysis of both the celebration of Crazy Rich Asians, and at the same time, if you want to see Asians on screen, there are other venues. I mean, I loved Minari. I thought that was great. I thought Fresh off the Boat was great. I saw things on that show that I never thought I’d see on mainstream, network TV. I mean, it is an incredibly low bar, but again, it is driven by the market. I know there are lots of critiques, and I know that Eddie Huang has distanced himself from that show—it is problematic, but everything is problematic in some way.

VP: Yeah, that is a different discussion, but I do feel like a lot of these cultural critiques via the shows and movies were valid at the time. I remember the 1990s Vietnamese CD shops, where there were huge contingencies of Vietnamese rappers in SoCal that were emulating gangster rap. It was corny and very much the things stuff you see with your parents on Paris By Night, lite-gangster rap.

PT: It’s like Vietnamese cosplay, playing rappers.

VP: Yes! It is sort of cheesy, but I also saw it as a tableau, which was part of the development of Vietnamese-American culture trying evolve with the times but also trying to keep something from the homeland. It is difficult and you could never do it in a way that was successful artistically and have it be commercially viable. So, I mean, I would love to hear about future works of yours dealing with some of that.

PT: Do you know the term mimesis?

VP: Yes.

PT: So, I think in Vietnamese-American culture, I think the ability to copy and sound like a thing is almost more celebrated than doing anything original. I used to be in a band in high school and my grandparents would ask if I could play the Beatles. I couldn’t play any of those songs so I played them one of mine and they would ask, “who wrote that?” I would say, “me, I wrote it,” and they would say, “but we don’t know it. Play something we know.” It was very much, can you copy the thing? It’s like karaoke or copying a painting of horses, we want you to be a skilled technician and reproduce things we already know and love. We don’t want you to do anything original because we don’t know it. It’s very interesting. It’s adjacent to your assessment about Vietnamese rap. It’s like cosplay.

VP: That’s interesting. So you mentioned Viet Thanh Nguyen and Ocean Vuong, and I just finished On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, so it is fresh on my mind. But were there many other Vietnamese-American authors you read growing up as a teenager, who stood out to you? Not to emulate, but made an impression?

PT: No, no. When I started working on my book, it was 2016. At that point, my definition of success was to write a book that only Phuc could have written. So I really siloed myself from reading Viet and Ocean, until after I finished my book. The only book I read before that was Andrew Pham’s Catfish and Mandala. I remember when that came out in the late 90s. My brother actually bought it for me and said, “dude, here is like a Viet guy who wrote a memoir about his experience.” We just never thought we would see that in our lives. Because if Asians make up 6% of the American demographics, then Vietnamese people make up such a small number of that, so we just never thought we’d see a lot of representation in any kind of media. So I hadn’t read any of their work, mostly out of my own process.

After I finished my book, I read Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do and Viet’s The Refugees, The Sympathizer, and Ocean’s book. It was all very rich, and like the diaspora it was very complex and paradoxical. I feel like I am leaving somebody out now and I’m doing to feel really bad about it [laughs]. I am really looking forward to more of that complexity coming out. I hope we make space for more Vietnamese American narratives that aren’t trauma porn.

VP: Yeah, I didn’t read your book as trauma porn. To me it was very much an American novel. This is a lot of teenage angst against Vietnamese parent, I relate to this. So more on this, what do you think about your kids reading your book when they’re older, and how do you feel having written the book reflecting on your parents, how do you feel about yourself as a parent?

PT: Oh, you know, I just told my kids they should be sixteen before they read it. I’m fine with them reading it. I just want them to be cognitively and emotionally abled to appreciate it and register the complexity of the story. I don’t want them to read the book and just think that it’s sex, drugs, and rock & roll, because it’s not. So that’s my answer, if they want to read them, they don’t have to. It’s just very hard to accept people as a whole human being. That said, if they do want to see me as a whole human being one day, there it is in the book.

You know, I went into therapy in my thirties specifically because I learned I was going to become a parent. It really triggered a recognition that I should really deal with my own shit. I’ve said this before but I think it is worth saying until I am blue in the face—my wife and I were trying to have kids, and we had been trying for a while—all of a sudden I thought about what it was like to be a son, and I didn’t feel good.

I didn’t like being a son. I didn’t have warm fuzzies, visions of fishing trips, bike rides, and that what when I said, “well, I should go to therapy, because if that’s the energy I am bringing to being a dad, then it is not great.” It was the very least I could do for my kids, to figure out my shit about what I think it all means, and how I could be the best dad. And trust me, they will probably go to therapy, too. I’ll probably fuck them up in my own special way.

The other reason I went to therapy was because I didn’t want to parent my kids the exact opposite way that I was raised. That’s not thoughtful parenting, that is just reactive. So, when at my best, I want to recognize my kids’ full humanity, I want them to feel seen, valued, and understood. In that way, it was very much the opposite of how my parents raised me. [laughs] It was very, I don’t want to see you, I am not really interested in learning who you are, and your value in the family is marginal. [laughs] I’ve a arrived at a place where I am not reactive.

VP: Well, I am sure they will have a lot of fun figuring out who their dad was.

PT: And maybe they will also read between the lines and see who I was as an adulting writing it. I really just wanted to write in the space of who I was, as opposed to a revisionist history. I didn’t want it to feel like that. Sometimes in the moment, there is no moral to the story.

VP: Right, of course. Well thank you so much for sharing your story.

PH: Thank you, and I wish you luck.

You may like

-

Dust Child (Book Review)

-

In search of what I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải

-

The Vietnamese American community in its early days: Bolsa then and now

-

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 16 – Stories from Yen & Kevin

-

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 15 – Hanoi at Midnight

-

Trần Văn Tùng’s Vision of a New Nationalism for a New Vietnam (excerpt)

Frustrated Nations: The Evolution of Modern Korea and Vietnam

Lại Nguyên Ân Revives the Portrait of Phan Khôi Once Again

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 22 – Subjects and Sojourners

“First Thắng, Second Chinh, Third Thanh, Fourth Trưởng”: The Four “Incorruptible” Generals of the ARVN

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 21 – Living Abroad

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

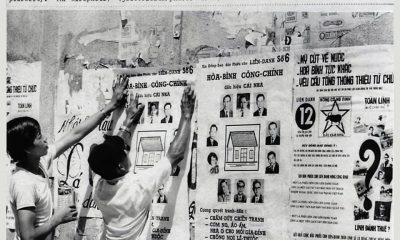

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

National Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoChina’s Recent Invention of “Nanhai Zhudao” in the South China Sea (Part 2: Examining the “Nanhai Zhudao” legal basis)

-

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)