Editor’s Note: Parts of this text has been redacted for style while the translation of the original work remains untouched. The poem is accompanied by a biography of the author and a personal essay written by the translator, as well as an interpretive analysis.

A tribute to Thanh Tam Tuyen, South Vietnamese poet and novelist (1936-2006) and Le Da Xanh (Crying Green Jade)

CRYING GREEN JADE

tôi biết những người khóc lẻ loi

không nguôi một phút

những người khóc lệ không rơi ngoài tim mình

em biết không

lệ là những viên đá xanh

tim rũ rượi

I know of those who cry alone,

non-stop

Those whose tears never roll out of their heart

Don’t you know

tears are green jade

from a heart that wilts

đôi khi anh muốn tin

ngoài đời chỉ còn trời sao là đáng kể

mà bên những vì sao lấp lánh đôi mắt em

đến ngày cuối

Yes sometimes I want to believe

out there life still holds those stars of significance

‘cause next to them your eyes still sparkle

till our last moment

đôi khi anh muốn tin

ngoài đời thơm phức những trái cây của thượng đế

mà bên những trái cây ngọt ngào đôi môi em

nguồn sữa mật khởi đầu

Sometimes I want to believe

out there life still emanates the intoxicating fragrance of God’s fruits

And next to them, the sweet taste of your lips,

our honey milky way of origin

đôi khi anh muốn tin

ngoài đời đầy cỏ hoa tinh khiết

mà bên cỏ hoa quyến rũ cánh tay em

vòng ân ái

Sometimes I want to believe

out there life’s full of wild flowers’ purity

And next to them, the lure of your arms,

our circle of love

đôi khi anh muốn tin

ôi những người khóc lẻ loi một mình

đau đớn lệ là những viên đá xanh

tim rũ rượi

Sometimes I want to believe

those who cry alone

feel their tears held within

muffled,

pained like green jade

from a heart that wilts

Green jade,

Oh crying green jade,

from a heart that wilts

DNN ©May 8, 2022

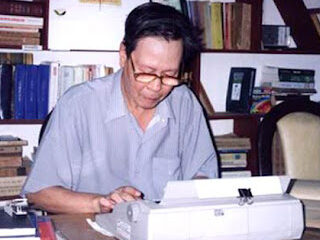

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE ON THANH TAM TUYEN:

Thanh Tam Tuyen (acronymed “TTT”) was a refugee from North Vietnam in 1954, right after the Geneva Convention divided Vietnam into two zones: communist North versus non-communist South.

TTT (meaning “Pure Ebony of the Art”) is the pen name of Dzu Van Tam, co-founder of the literary and cultural magazine Sang Tao (“Creativity”) in South Vietnam. (The word “Tuyen” can also mean “a stream,” so the pen name TTT can also mean “Stream from the Pure Heart”).

With this magazine as his “literary child,” TTT started the “free verse/poetry in prose” movement in South Vietnam in the 1960s, thereby transforming Vietnamese poetry for the later half of the 20th Century, at least in the South. He also wrote novels and essays, conveying refreshing philosophical themes and a new literary style, which I consider to be ground-breaking for his generation in South Vietnam, during his time as well as thereafter. An eloquent teacher, TTT was well admired by, not only readers of his work and poetry, but also generations of his students.

Following the fall of Saigon in 1975, he was sent to a reeducation camp by the new regime. After years of hard labor and imprisonment, TTT immigrated to the U.S. as part of the Reagan-Bush Administration’s “HO” program, and settled in Minnesota, where he lived a quiet, secluded life until his death in 2006.

Among TTT’s most famous “free verse” poems is Le Da Xanh, which I subjectively translated as “Crying Green Jade” (see Appendix 1 for my personal essay).

Le Da Xanh was set to music by two of South Vietnam’s best-known songwriters, Cung Tien and Pham Dinh Chuong (i.e., two separate songs). Both musicians were South Vietnamese refugees who settled in the U.S. after 1975.

In my opinion, the version composed by Cung Tien (“CT”) (see Appendix 2), in particular, bears certain characteristics of, and influence from, the impressionistic and melancholic nature of the early 20th Century’s Romantic (or post-Romantic) composers of the West such as Debussy and Satie, although the tonal nature of Cung Tien’s composition remains intact (contrasting against what was pioneered as atonal trends in the West, but not yet introduced to, pre-1975 South Vietnam).

The following personal essay is based on what Le Da Xanh, the poem and the song, means to me — that which inspires me to write.

ABOUT LE DA XANH: MY CRYING GREEN JADE

Both Uta Hagen and Lee Strasberg will agree, and so will Maria Callas, who thinks of herself as the servant of music: performing artists, whether in the vocal art or drama, must reach deep down in their soul and find something at the core of their existence to rely on, in order to express themselves. That’s the private sphere of the artist’s soul, to be given selflessly to that which he/she expresses…

Everybody whom I knew from the imperial city of Hue knew that my maternal grandmother was among Hue’s most beautiful women.

Grandma wore a jade bracelet all her life. It became greener and greener as she aged.

Memory of childhood in Vietnam often got me back to those nights in Hue, when Grandma held me in her arms, and I felt asleep. Nighttime in Hue could be cold and rainy, but she kept me warm.

In the middle of the night, often I woke up and felt something cold: It was a pleasant cold, smooth and pure, from a dainty object, like a slender, polished cut of stone on which I could lean and rest my cheek.

It was her jade bracelet, of course, pressed against one side of my face. I felt asleep again, her breath over the top of my head filtered down and warmed up her jade bracelet, I was sure. But the cold lingered on, cooling my cheek, like a cold thread of silk, piercing through the warmth of her breath.

I felt safe in that pleasant cold, my pleasant cold, isolated in all that warmth to anchor me.

***

But then I felt something else.

A tear must have somehow landed or emerged, smearing itself onto her jade bracelet. I must have heard the sound it made, like a rain drop. Or a tiny, gentle crack.

Distinctly, it had to be one single tear. At least, that was what I thought, intuitively, that one night.

***

Was the jade crying, or was it Grandma?

Childhood’s deep sleep took over always, those nights in Hue.

My little self was not burdened by the weight of thoughts, so I never knew for sure where the tear came from.

***

Time rolled like the Karma wheel, and her jade bracelet was eventually passed on to me, marking my teenage days, my coming of age. I wore it on the night I stepped on the C130 cargo plane at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhat airport.

Onto America.

Without Grandma.

I was forced to forget.

Yet the jade bracelet became a perpetual piece of jewelry. A continuing existence. It spoke of who I am and where I came from.

At times I forgot that it was on my wrist.

***

One day at the University’s Recreation Center, I went swimming and was doing the backstroke. The goal was: if I learned music and chose a writing career, I had to learn physical education to achieve balance.

In that one swim, as I was about to finish the round, like destiny, I felt so distinctively that my wrist had hit the wall of the swimming pool, as my arm reached over my head to push myself ahead, darting on in all that Clorox-smelling water.

I couldn’t hear any sound of breakage in all that water, but I knew something had happened. Instinctively I turned myself into a somersault, dived down without preparation, and looked deep in that water. I saw the bracelet, broken in half. The two halves were falling down, separately like two entities. The two pieces would never find each other again.

And then in all that Clorox-smelling water, I felt Grandma around me. I felt the coldness of the dainty cut of stone pressing onto my cheek. I was safe against that pleasant coldness, upon which I relied. Upon that cut of smooth stone I leaned.

I felt, too, the one tear that wetted my cheek as though it were parting the water to become its own space.

The jade was tearing, or Grandma was tearing.

The jade bracelet that defined me was gone, broken into two halves, falling down and down and down, separated from me forever, into that bottomless Clorox-smelling mass of engulfing water…

America.

***

The swimming instructor said that day, I almost drowned.

But somehow before the instructor could jump in or throw a float to help, I had gotten myself back up. I emerged from that water by myself, and got off the swimming pool.

Honest to truth, I can’t remember what happened next.

Part of me has always blamed America for the loss of the bracelet. Part of me has blamed myself.

And then I learned what finally had to come as the obvious: Grandma died alone in my former Saigon, in solitude, without food and medicine.

***

In my own American womanhood, I moved on and then in 1994, I decided to take a long leave of absence from my judgeship, in order to return to Vietnam as an international lawyer after Clinton’s lifting of the trade embargo against Vietnam. Throughout those years, I discovered the chapters of Grandma’s life (1910-1979). There were enough events hidden in her heart to cause her tears. Events of her family. Events of her Hue, and events of the whole country – why the jade became greener and greener as she aged: that which caused the one tear I felt on that jade circling her wrist, in my dormant Vietnamese childhood.

I came to learn the silence of that one tear. The silence of green jade. The silence of Grandma’s heart.

The silence of my loss in America.

***

And that is what the performing artist in me will rely on, in delivering Cung Tiens’ Le Da Xanh. To myself. All I need was the coldness of the cut of stone resting against my cheek, upon which I relied, one night in Hue.

I don’t need the orchestra. Please dismiss it and make my stage bare and simple. Please give me that one tear in the sound of your lonely guitar that speaks to me the silence of Grandma’s green jade.

The solitude of the green jade that cried.

The solitude of Grandma’s heart that cried.

The solitude of her Hue night that cried.

The solitude of that one tear I felt in the tenderness of Grandma’s arms.

The solitude of my stage.

The one tear on stage this night speaks of my loss, of Grandma’s sufferings and all the secrets she bore. What was buried in her heart.

Her Vietnam.

***

That one tear, unspoken, yet spoken, like the delicate notes — half tones and whole tones — to circle into the words they become. Worn upon a Vietnamese woman’s wrist, pressed against her forehead, her cheekbone, and then her heart.

Thank you, Cung Tien and Thanh Tam Tuyen.

(c)DNN 5/7/2022

APPENDIX 1: About the translation

OF MEANING AND INTERPRETATION: Lệ đá xanh – Crying Green Jade

“Crying Rocks” are literary motifs and images found in American contemporary literature based on American Indian folklores and heritage.

In contrast, concepts of an age-old rock that held memory of tales through thousands of years as witness of life events and history were part of the foundation for ancient China’s epic novel/metafiction, Hong Lau Mong (Dream of the Red Chamber).

In Vietnam’s classical heritage, the personification of rocks and waters became literary symbol of the culture. For example: “Da van tro gan cung tue nguyet, nuoc con cau mat voi tang thuong” (“Rocks sustained their formation against wear-and-tear from the test of time; water frowned at life’s upheavals that transformed seas into berry fields”), quoting Ba Huyen Thanh Quan, Vietnamese poetess, 19th Century.

TTT transposed these ancient concepts into modernity, as birth (or rebirth) of a new (or rejuvenated) literary motif. Unique to his free verses, Le Da Xanh reflects the silenced psychic pain of his generation in absorbing loss, despair, and disillusion.

I chose the phrase “Crying Green Jade” to interpret the title. It was the only phrase I could think of, in order to denote and combine two different semantic possibilities drawn from TTT’s original language:

1) Tears themselves become green jade, i.e. the poet cries and his tears turn into green jade; or

2) Tears are held back in the poet’s heart, so the heart may cry out, but tears are withheld within, frozen through time, meaning the palpitating heart is eventually crystalized or solidified into green jade.

Both concepts are metamorphosis that only poeticism can project.

I have also added English words that denote silenced or suppressed pain — the poet’s tender heart becomes the reservoir of tears, symbolizing inner strength and endurance.

In contrast to Red as the color of blood, a “heat” symbol standing for Life, TTT spoke of Blue as either sapphire blue or emerald green, a “cool” tone in the art of painting, signifying coolness or coldness, denoting solitude or lonely efforts at rejuvenation, after losses, sufferings, or bloodshed. Blue is the color of hope – the hope of Art.

I chose “jade” as my interpretation because of its cultural meaning – the precious-stone ornament associated with the Vietnamese female motif and image of femininity.

However, to interpret TTT’s poem as relating only to a couple’s love is to belittle the poet’s philosophical temperament and message about Vietnam’s pre-destined sufferings, found all throughout his written works. Le Da Xanh also reflects the largesse of his soul and thoughts – he spoke of sufferings as fatalism, which I construe to mean the image of a Vietnamese Sisyphus. Sisyphus to me is a generous laborer. There, TTT spoke clearly of the larger scope: the collective tears: Le Da Xanh…oi nhung nguoi khoc le loi mot minh — tears from those who cry alone. (In his later poems composed during his “re-education camp” imprisonment, TTT described the silent heroism of political prisoners in drawing their strength from a glimpse at springtime outside their cells, or from their arduous climb, against shackles and wounds, to drag themselves up the hill during forced labor, as springtime beckoned their bony legs. This springtime image serves as comparison to, and contrast against, Beethoven’s heroism and musical reverberation in deafness — testament of the human spirit against adversity.

I have also added English words to TTT’s reference to Christianity as the European addition to Vietnamese collective epistemology: concept of the seductive Apple displayed to a suffering human being by a creator-God. This point is significant to me because it shows the poet’s humanity and his belief in love and free will – the poet is not an atheist like his indoctrinated North Vietnamese Marxist counterpart.

Le Da Xanh is a short and seemingly simple poem, yet packed with images, ideas, and emotions, cast into the best form of Vietnamese abstractionism. My goal is to express the poem in the simplest form of the English language.

I have chosen this poem because I think it speaks of the cultural and artistic life of South Vietnam as part of early nation-building, for which TTT was a symbol as well as an important witness of history. The musical adaptation has made the poem last, as it is being sung in Vietnam today (see Appendix 2).

I must dedicate this essay and my English translation of the poem to my late father, who introduced TTT’s work to me when I was just a child in Vietnam. I believe my father authored the only published literary critique of TTTs famous novel, Dọc Đường (“Along the Road”). Ref. Dương Đức Nhự, “Đọc Dọc Đường cuả̉ Thanh Tâm Tuyển” (“Upon Reading ‘Along the Road’ by Thanh Tam Tuyen”) (1960’s). Published in literary journals of South Vietnam, my father’s critique was not archived, and hence, can no longer be located after 1975.

©DNN Mother’s Day, 5/9/2022

~~~***~~~

APPENDIX 2:

The featured video performance is what I consider to be the best performance of the song Le Da Xanh written by Cung Tien, coming out of today’s Vietnam, to date:

Cung Tien’s Le Da Xanh, based on TTT’s poem, performed in Qui Nhon, Vietnam, 2022, by Dam Ha and Dieu Nhan. (Fair use exception to copyright)

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago