Politics & Economy

Toward National Buddhism: Thích Nhất Hạnh on Buddhist Nationalism and Modernity in the Journal Phật Giáo Việt Nam, 1956-1959 (Part 2)

Published on

Editor’s Note: The following article was published in the Journal of Vietnamese Studies, Vol. 19, Issue 1. The study details the life of Thích Nhất Hạnh and his involvement with Buddhist nationalism. This is part two of the article, which includes the final two sections. To see part one, click here. No content changes have been made.

On Buddhism, Democracy, and Nationalism

Thích Nhất Hạnh’s writing for PGVN shows he was a fervent nationalist who engaged with questions of modern nation building through the lens of Buddhism. He proclaimed that “the most concrete and perfect form of societal organization is the nation.”[54] Like others across the decolonizing world, Thích Nhất Hạnh believed national independence was a necessary step toward modernization, development, and prosperity.[55] In PGVN, he upheld Buddhism as a religion uniquely suited for democratic nations in general and the Vietnamese nation in particular.

To Thích Nhất Hạnh, nations were the most perfect form of social organization because they have the unique ability to unify people around a shared set of beliefs.[56] As he explained, the foundational beliefs of a nation inform everything else in society, from family relations to everyday ethics to governance. The right belief system would promote democracy, he claimed, and would prevent the nation from going down the path of “dictatorship, autocracy, oppression, and conquest.”[57] Although Thích Nhất Hạnh embraced the twentieth century as an age of scientific experimentation and rational thought, he asserted that religion—loosely defined as unwavering faith in a god or set of beliefs—remained unparalleled in its power to unify and mobilize human societies.[58] Beliefs in science and secular values were still not as strong as religious faith when it came to unifying and influencing people, he held. Thích Nhất Hạnh observed that even modern political ideologies like communism were organized as if they were religions. The Communist Party revered its tenets as if they were a god, he wrote, using them “to summon and focus the beliefs and spirit of the people” and to create “the religion of Communism.”[59] In short, Thích Nhất Hạnh identified the nation as the ideal form of social organization, and shared faith as its core unifying element. In his view, religion was the most effective force for uniting and guiding citizens toward a shared ideal.

Thích Nhất Hạnh asserted that Buddhism was the religion best suited for modern nations, given the “democratic” nature of Buddhist philosophy.[60] While he never provided an explicit definition of democracy in his articles, his examples show that he believed its defining features were egalitarianism, individual freedom, and collective responsibility—and that these qualities were already inherent in Buddhism. Thích Nhất Hạnh began drawing connections between Buddhism and democracy during his novice years in Huế. In an essay reflecting on his time at Từ Hiếu temple, he described a conversation he had with a friend “on the topic of equality and democracy in Buddhism.”[61] The two young novices “were delighted to see that these qualities that were so highly valued in society were also inherent in Buddhism” and that “no other religion allows people to see themselves as equal to its leaders in regard to their innate nature and potential.”[62] In Buddhism, Thích Nhất Hạnh explained, there is no god. The Buddha was just a human who taught others about the spiritual path he had discovered.

This meant that egalitarianism was foundational to the religion, he claimed, because it is believed that everyone can achieve enlightenment just like the Buddha. Another example Thích Nhất Hạnh cited in this essay is a story that was passed down orally through the generations at Từ Hiếu. The story goes that one day, King Thành Thái (1879–1954) came to visit Master Hải Thiệu at the temple. The king and the Zen master greeted each other respectfully yet familiarly, like old friends, and shared a humble snack of steamed cassava. “There is truly nothing more democratic,” Thích Nhất Hạnh wrote, “than the image of a king visiting a monk and being invited by the monk to eat cassava with him” (emphasis added).[63] The respect shown by King Thành Thái toward Master Hải Thiệu was admirable, he added, but the down-to-earth attitude exhibited by the Zen master toward the king was even more worthy of esteem. What Thích Nhất Hạnh appreciated most about this story was that Master Hải Thiệu did not shrink in the presence of the king, but rather treated the king as a respected peer. These examples suggest that in Thích Nhất Hạnh’s view, upholding the inherent value and equality of human beings—regardless of social or political rank—was a core element of both democracy and Buddhism.

Another core aspect of Buddhist philosophy that Thích Nhất Hạnh identified as democratic is its emphasis on individual freedom and responsibility. Since there is no divine being or supernatural power in Buddhism, he pointed out, “individuals determine their own future and take responsibility for their actions”—just as citizens in a democratic society are responsible for their actions and the impact they have on the collective.[64] Furthermore, Thích Nhất Hạnh wrote, Buddhism encourages people to seek truth through their own exploration and lived experience, rather than simply believing what they are told. “The spirit of free inquiry is the most precious thing about Buddhism,” he stated. “Buddhism does not tolerate dictatorial thinking.”[65] Because individuals have the ability to chart their own way, they have a responsibility to society, Thích Nhất Hạnh elaborated. The thoughts, actions, and speech of each person impact the welfare of the nation as a whole. On the flip side, individual welfare is also shaped by societal context. “Buddhist philosophy offers us a worldview,” he stated, “based on the inter-relatedness of individuals and society.”[66] Returning to the question of what belief system is best suited for modern nations, Thích Nhất Hạnh claimed that because it upholds personal agency and responsibility, as well as the mutual relationship between individual and collective wellbeing, Buddhism “truly suits the spirit of democracy in modern society.”[67]

Thích Nhất Hạnh’s description of Buddhism as egalitarian, atheistic, and supportive of free inquiry reflects the views of reformist Buddhist intellectuals starting in the 1920s. A major initiative of the Buddhist revival was to encourage the study of Buddhist sutras and philosophy so that the faithful would have a solid grasp of their actual meaning instead of practicing blind worship.[68] However, it cannot be said that the majority of Vietnamese Buddhists in the 1950s studied the texts translated by reformist leaders or attended the public lectures meant to educate them about the Dharma. Many still prayed to the Buddha as if he were a deity or believed in superstitions like holy potions and charms. Thích Nhất Hạnh’s portrayal of Buddhism as modern and democratic was therefore more aspirational than descriptive; he was expressing the unrealized ideal of how reformed Buddhism could support democracy, rather than depicting the popular understanding of Buddhism in the 1950s.

Besides portraying the core philosophy of Buddhism as democratic, Thích Nhất Hạnh also argued that Buddhism would be a good basis for nationalism because it is flexible enough to encompass diverse philosophies and can adapt to different places. Given that Buddhism had been able to survive and thrive for centuries by conforming to different cultures across Asia, he saw adaptability as one of its main strengths. “Some people want Buddhism to be the same everywhere—all one color, one organization, one form. But those people are mistaken,” he wrote. “Buddhism has always changed with the times and adapted to wherever it is.”[69] He proposed that Buddhist leaders should promote their own flavor of Buddhism wherever they are—their own “unique, independent Buddhism,” true to the customs and traditions of their people.[70] This, Thích Nhất Hạnh believed, would lead each country to peace and prosperity.

There is an inherent tension between celebrating the diversity of Buddhism and calling for its uniformity at the national level. In the case of Vietnam, Thích Nhất Hạnh acknowledged that many Buddhist sects and practices existed in the country and that there was no singular version of Vietnamese Buddhism. Some Buddhists followed Theravada and others Mahayana schools; temples had different architectural designs; monastics wore yellow, red, or brown robes and performed various rituals; some devotees ate a purely vegetarian diet while others only gave up meat on certain holidays.[71] Still, to Thích Nhất Hạnh, all these differences were “meaningless in the face of national Buddhism.” He boldly claimed “There is only one Vietnamese Buddhism which is traditional and historical; there cannot be any other kind of Buddhism” (emphasis original).[72] In PGVN, Thích Nhất Hạnh often referred to what he described as the “golden age” of the Lý and Trần dynasties and the deep influence of Buddhism on Vietnamese culture and the nation dating back to the eleventh century.[73] This was a common narrative propagated by Buddhist revival thinkers—for example, a 1942 article in Viên Âm stated: “The relationship between Buddhism and the spirit of the Vietnamese nation is very firm. This is because Buddhism is well suited for our culture and heritage, and because many generations of ancestors have passed it down to us in our blood and bones.”[74] Thích Nhất Hạnh repeated the assertion that despite the existence of diverse styles and practices, there was only one true Vietnamese Buddhism.

Like other Vietnamese nationalists, Thích Nhất Hạnh felt the need to address the historical and cultural entanglement of Vietnam and China. Specifically, he sought to differentiate Vietnamese Buddhism from Chinese Buddhism by showing that the former had its own distinct history and doctrine. He explored these unique aspects of Vietnamese Buddhism in a series called “Toward National Buddhism,” published in PGVN from March to June 1957, starting with reexamining the historical patriarchs who had brought Buddhism to Vietnam. Many Vietnamese temples in the twentieth century maintained an altar for Bodhidharma, the monk credited with bringing Zen Buddhism to China in the sixth century CE. Thích Nhất Hạnh proposed that instead of honoring Bodhidharma, Vietnamese should recognize a different Buddhist ancestor, Vinītaruci [Tỳ-Ni Đa-Lưu-Chi].[75] This was a new idea that had not been proposed by earlier Vietnamese Buddhist reformers. While Bodhidharma went to China from India and propagated Buddhism there, Thích Nhất Hạnh explained, Vinītaruci continued south through China to bring Buddhism to Vietnam. Rather than worshiping the Chinese Buddhist patriarchs, he wrote, “We must worship the ancestors of Vietnamese Buddhism to maintain a sense of our 1,500 years of history.”[76] Later in this series, Thích Nhất Hạnh highlighted a Buddhist sect that had developed in Vietnam in the thirteenth century but did not exist in China: the Trúc Lâm Yên Tử Zen school.[77] To Thích Nhất Hạnh, recognizing the unique history and development of Buddhism in Vietnam was an important step toward building national Buddhism. “In the past, the task of establishing a unique Vietnamese Buddhism was already initiated,” he claimed. “Today we have to complete it.”[78]

Thích Nhất Hạnh’s discussions about nationalism and democracy in relation to Buddhist history and philosophy are evidence that he was truly a student of the Buddhist revival. Like reformist thinkers before him, he highlighted Buddhism’s rational philosophy and democratic values and was determined to prove its usefulness in a modern, nation-based world system. Reformist Buddhists across Asia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries put forth their religion as a foundation for non-European modernity. As the French scholar Paul Demieville observed, Buddhist revival leaders endeavored “to show that the Occident has invented nothing,” that Buddhism was essentially democratic, humanistic, rationalistic, and existentialist before Western philosophers coined these terms—and that “one need only reform [Buddhism] to adapt it to the modern world and put it in a condition to stand up to Christianity or even to Marxism.”[79] Given this international context, Thích Nhất Hạnh’s assertions in PGVN could be read as an indirect criticism of other religions, especially Western or deist ones. His claim that Buddhism is especially suitable for democracy because it is atheistic and supports freedom of inquiry could be interpreted as a claim that religions that uphold belief in a god or a strict doctrine would more likely lead to despotism or autocracy. Additionally, if he believed Vietnam historically thrived as a Buddhist nation, it could be inferred that he saw other religions as inherently foreign and anti-nationalistic. However, while Thích Nhất Hạnh claimed Buddhism was best suited for democratic nationalism, he never explicitly named other religions as backwards or harmful to modern society and did not express his views on other religious nationalist groups. His extensive collaboration with Catholic and Protestant leaders in the 1960s shows that he saw them as partners in providing moral and ethical guidance in a war-torn world.[80] Within the pages of PGVN, Thích Nhất Hạnh strongly advocated Buddhist nationalism without any caveats because it was a Buddhist magazine. He likely did not explore the nation-building potential of other religions because he was writing with the sole intent of galvanizing a Buddhist audience.

It is worth noting that the orthodox Buddhists of the revival movement were not alone in asserting their religion’s unique role in the Vietnamese nation and the modern world. Other religious groups faced a similar challenge of vying for influence as their country was decolonizing. The Hoà Hảo sect also claimed to have a historical role in Vietnamese nationalism, finding its origins in ethnic Kinh Vietnamese pioneering and settlement in the Mekong Delta region. Like the outlook promoted by the Buddhist revival movement, the core beliefs of Hoà Hảo are nationalistic, anti-superstitious, and include a universalist vision of global harmony and interdependence.[81] The Vietnamese Catholic reform movement of the 1920s–1930s had many aspects in common with the Buddhist revival. Catholics, too, felt the need to update their religion to compete with the rise of secularism and communism. They focused on indigenizing their clergy, expanding their print sphere, updating schools and seminaries, and developing lay associations to facilitate the social and educational activities of the church.[82] Perhaps feeling threatened by other groups’ claims of national indigeneity, Nguyễn Bá Tòng, the first Vietnamese bishop appointed by the Vatican in 1933, criticized non-Catholic religions as being “rooted in human dogmas and incapable of adapting to the challenges of modern life.”[83] He specifically called out Buddhism, Confucianism, and ancestral worship and claimed that only Catholicism could unite the modern world with its timeless message of love and charity. Religious leaders of every faith posited that their religion was the best for the future of the Vietnamese nation and humanity more broadly.

During the era of the struggle for Vietnamese independence, many believed Buddhism must be understood and developed as a national heritage. Thích Nhất Hạnh echoed earlier revival thinkers in writing about the historical role of Buddhism in Vietnamese society and ways in which modernized Buddhism could guide the country into the future. To truly influence the direction of their nation, however, Vietnamese Buddhists would need more than theoretical discussions. They would have to combine their resources and organize themselves at the national level. Thích Nhất Hạnh used PGVN to bring this challenge to light and push for progress toward what he called the “complete unification of Vietnamese Buddhism.”[84]

Toward a Nationally Unified Buddhism

The founding of the GBA in 1951 was a major step toward Buddhist unification in Vietnam, but it was mostly symbolic. While the GBA brought together groups from all three regions of the country under one umbrella, it was more of a federation, as its eleven member organizations retained their own statutes and structures. Truly unifying Vietnamese Buddhists under one formal organization—with a centralized administrative structure, educational program, and standardized practices—remained an uphill battle. In PGVN, Thích Nhất Hạnh documented the unsteady progress made toward the nationalization of Vietnamese Buddhism—and became its most fervent advocate. This is where he differentiated himself from the first generation of Buddhist revival thinkers. Going beyond theoretical discussions, he advocated concrete steps toward a truly centralized national Buddhist organization.

At the founding conference of the GBA, a central committee was elected to “swiftly carry out the program of unification” that was part of its charter.[85] However, the process of turning symbolic unification into a tangible reality was slow. On the occasion of the GBA’s sixth anniversary, Thích Nhất Hạnh dedicated that month’s PGVN issue to the topic of unrealized national Buddhist unification.[86] He pointed out that, after more than half a decade in existence, the GBA was little more than a committee of regional representatives with no real influence. “The General Buddhist Association was established six years ago, and in those six years we have still not made complete unification a reality,” Thích Nhất Hạnh wrote. “We haven’t been able to reach the second stage that we intended: the stage of dissolving the six separate groups in order to have total unification.”[87]

Given that Buddhist unification was ratified unanimously at the GBA’s founding conference, one might question why it was so difficult to carry out. According to the association’s vice president, Lê Văn Định, the GBA faced two main challenges: (1) legal and political hurdles and (2) a lack of interest and manpower from the regional groups.[88] After its founding in May 1951, it took over two years for the State of Vietnam to grant the GBA the right to operate legally.[89] Soon after they received formal recognition from the government, the 1954 Geneva Agreement divided the country in two and the GBA continued to operate only below the seventeenth parallel. Two hundred thousand Buddhist refugees from the north were officially incorporated into the GBA in 1956, but according to Lê Văn Định, they struggled to find their footing and were unable to contribute significantly to the organization.[90] Local and regional groups carried on their work under the GBA name, their major achievements being the construction of the Vietnamese Institute of Buddhist Studies in Nha Trang as well as Xá Lợi pagoda in Sài Gòn.[91] Still, it proved extremely difficult to build up a unified national organization in a country that was formally divided. The other significant hurdle to unification was getting buy-in from local and regional leaders who were accustomed to functioning autonomously. According to Thích Nhất Hạnh, many Buddhist leaders were still not convinced that true unification was necessary, even though they had supported the symbolic founding of the GBA.[92] The regional Buddhist associations, established in the late 1920s and early 1930s, had only been around for about twenty years when the GBA called for them to join forces. Before that, there were no formal organizations at all beyond individual temples. Looking at the long history of Buddhism and seeing that the Dharma had always been passed down without formal organizations, many people thought national unification was only creating unnecessary work and formalities. Additionally, there was a general shortage of Buddhist leadership and personnel. There weren’t enough people to take care of growing local communities, much less people willing to move to Huế or Sài Gòn to support the central administration and development of the GBA.[93]

Thích Nhất Hạnh was frustrated by the continued dominance of regional structures and programs, seeing themas a barrier to large-scaleBuddhist action. Two years into editing PGVN, he became increasingly vocal about his concerns. In a series titled “Why We Need to Unify Vietnamese Buddhism,” published from September 1958 to March 1959, he laid out why he believed a centralized national organization was necessary. Under the current circumstances, Thích Nhất Hạnh explained, Buddhist spiritual and material resources were divided and scattered: everyone was organizing their own lectures, ceremonies, youth associations, and educational programs, and they were not sharing knowledge or experience with others.[94] Sometimes the work of different Buddhists came into conflict with one another, he noted, such as when multiple scholars carried out different translations of the same text. Furthermore, he complained that it was impossible to represent Vietnamese Buddhists and their interests at a higher level, inside the country or abroad, without one nationally unified collective.[95] In his eyes, the persistence of siloed local and regional groups was a barrier to Buddhist progress and representation.

In addition to wasting their potential for significant impact, Thích Nhất Hạnh claimed the status quo would have dire consequences for the trust and morale of the Buddhist faithful. Leaders of the GBA would lose the respect of the people if they failed to carry out their stated mission, he lamented.[96] Seeing the inability of the GBA to follow through with its declaration of unification, he feared that Buddhists would lose faith in their leadership and, over time, give up on collective organization altogether. With little opportunity to interact at the national level, Thích Nhất Hạnh stated, Buddhists would be restricted to their local and regional groups and grow distant from each other. He illustrated his point with an example. Under the current situation, if two local Buddhist Youth Associations—say in Bình Thuận and Biên Hoà—wanted to host a joint event, they would have to go through three layers of approval from six committees: first their two provincial committees, then the two general committees of the central and southern regions, and finally the two executive boards of the central and southern Buddhist associations. A national conference would require a mountain of paperwork. The persistence of local and regional groups alongside a national association would stifle growth and collaboration, making people feel as if they were “locked in multiple cages, the smaller cage within a bigger one, and the bigger one within an even larger one,” he wrote.[97] In Thích Nhất Hạnh’s view, the decline of morale among the people and loss of momentum for the revival movement would be the most serious and lasting consequences of the GBA’s failure to carry out national unification. He saw their organization as the culmination of a long-held ideal of the Buddhist revival—one that the previous generation had been unable to bring to fruition. Thích Nhất Hạnh felt the GBA was on the cusp of a historical development for Vietnamese Buddhism and did not want their efforts to go to waste.

Despite resistance from less-than-enthusiastic local leadership, some centralized reforms were happening in the 1950s. The GBA aimed to standardize Buddhist beliefs and practices across the country; it specifically had plans to reform rituals and ceremonies, preaching, and education. Thích Nhất Hạnh covered these efforts in PGVN both to keep readers informed and to pressure GBA leaders to continue their progress toward a unified and centrally organized Buddhism. In addition to illuminating the hopes and ideals of national Buddhism, Thích Nhất Hạnh’s writing documents the institutional struggles and developments of Vietnamese Buddhism in the mid-twentieth century.

On the issue of preaching, the overall goal was to establish a common understanding of Buddhism for people throughout the country. As previously mentioned, a key aim of the revival movement from the 1920s to 1930s was to get the faithful to study and understand Buddhist teachings, rather than just practice and worship blindly. To this end, monks and scholars had begun to explain Buddhist sutras and concepts through print materials—like the regional magazines and smaller pamphlets—and regular public Dharma talks at temples.[98] As commissioner of preaching for the GBA, Thích Thiện Hoa’s main project was to further centralize the propagation of Buddhist teachings by building a national Buddhist preachers’ organization and a national Buddhist studies center where the central program could be researched and developed.[99] At the time of his interview for PGVN in August 1957, there were only about thirty monks on board with the GBA preaching program.[100] Thích Thiện Hoa’s optimistic analysis was that within two years of establishing the national program, people throughout the central and southern regions would have a shared foundational understanding of Buddhism.[101]

On the issue of Buddhist rituals and ceremonies, Thích Nhất Hạnh interviewed and received documents from Thích Tâm Châu, who was the commissioner of rituals for the GBA at the time. “The work of unifying rituals at the national level is very difficult,” Thích Tâm Châu admitted.[102] During his travels to many central and southern provinces, he had seen differences in practice even at the local level. The work of standardization had already begun, however. In March 1957, the GBA sent out an announcement to local Buddhist groups and temples that described the project and provided guidelines for local groups to follow.[103] First, each local group would establish a research committee—composed of monastics and laypeople—which would study and document the ritual texts, sounds, music, materials, and garb of their locality through written documents, audio and video recordings, and photographs. When the documentation was complete, a GBA delegation would come to collect and exchange documents with each local committee, allowing everyone to see, hear, and experience the rituals and ceremonies of other groups. After that, a national conference would be held to decide on a single set of ritual practices and holidays, which would then be popularized through classes, discs, and written manuals in quốc ngữ. Those rituals that were not adopted as the national standard would be preserved in a national museum of Buddhist culture.[104] The greatest difficulty, according to Thích Tâm Châu, was figuring out how to create rituals that would be meaningful to people all over the country, regardless of where they were from. Ceremonies and rituals had to be imbued with both religious meaning and nationalist spirit to be embraced by everyone, he said.[105] The experience of religious meaning is subjective, however, and even Thích Tâm Châu had personal opinions about what qualified as true Vietnamese Buddhism. He admitted that he disliked some newer songs written by the younger generation because they were “influenced by the West and lack the true spirit of Buddhism.”[106] The GBA’s process of standardizing rituals was not entirely democratic, either: although localities were still carrying out the first step of documenting their rituals, the decision had already been made to change the color of ritual robes for laypeople from brown to light gray.[107] The task of national unification was complicated given the diversity of existing beliefs and practices, as well as people’s desire to preserve their particular form of religious practice. It could be near impossible to convince different communities to give up what they saw as pure and traditional and embrace a new standard of Buddhism determined by a faraway national congress.

On the topic of monastic education and training, Thích Nhất Hạnh offered his own ideas for reform, drawing from his experience as a student and instructor at reformist Buddhist schools in Huế, Đà Lạt, and Sài Gòn. At the time, many Buddhist leaders were worried about attrition in their institutes and wanted to update their curricula to be more appealing to the young generation. This was the case at the Ấn Quang Institute, where Thích Nhất Hạnh was invited by Thích Thiện Hòa and other senior monks to develop a new training program for the novices.[108] The leaders at Ấn Quang were concerned that many monks and nuns of the new generation were either drawn to Marxist ideals or were leaving Buddhist institutes for secular programs in medicine and engineering. Thích Nhất Hạnh was therefore tasked with creating “a more relevant and inspiring Buddhist program” which would draw from the liberal arts and offer a diploma comparable to those awarded by the national universities.[109] In Thích Nhất Hạnh’s analysis, insufficient enrollment in Buddhist institutes would lead to broader structural problems since it would cause a shortage of monastic talent and leadership throughout the country. In PGVN, he elaborated on this issue and proposed a centralized and standardized education system as the solution.[110]

Thích Nhất Hạnh observed that while the Buddhist revival movement had given rise to many Buddhist youth organizations, temples, orphanages, and schools, these organizations lacked the key aspect of monastic leadership. At the time of his writing in June 1957, he noted that there were only three hundred novices in school throughout the country—not nearly enough to fill all the roles of public lecturers, schoolteachers, social workers, temple abbots, and so on.[111] If Buddhists were going to continue to strengthen the educational and social networks established by earlier revival leaders, they would need a much greater number of well-educated and qualified monks and nuns. The system that Thích Nhất Hạnh proposed would provide financial aid to lower or eliminate the cost of enrollment for novices from poor families. Its curriculum would include studies in Vietnamese, Chinese, French, and English languages in addition to the Dharma.[112] Monks would be trained primarily to become preachers and temple administrators, while nuns would be trained in childhood education and social services so they could run orphanages, teach children, and treat the sick.[113] Thích Nhất Hạnh’s proposal reflected a core idea of the Buddhist revival: the notion that a standardized monastic education system would produce qualified individuals to lead and serve Buddhist institutions throughout the country. He continued to champion Buddhist educational reforms in the 1960s. After returning from his studies abroad at Princeton and Columbia University from 1961 to 1963, he spearheaded the founding of the Sài Gòn College of Buddhist Studies [Viện Cao Đẳng Phật Học Sài Gòn], which would later become Vạn Hạnh University [Viện Đại Học Vạn Hạnh].[114] This was a private Buddhist university that offered degree programs in literature and arts, philosophy, sciences, and social sciences. The university proved appealing to many, and by 1974 there were more than seven thousand students enrolled across its four departments.[115]

In carrying out the mission to reform and unify Buddhism at the national level, the GBA had to contend with a formally divided nation and less-than enthusiastic local leadership. Thích Nhất Hạnh used PGVN to make the case for a centralized organization that would combine all Buddhist resources and talents, coordinate their efforts, and enable Buddhism to influence Vietnamese society at large. His writings pressured GBA leaders and members to keep making progress toward national unification. As the foremost advocate for national Buddhism, Thích Nhất Hạnh also had his eye on developments at the international level, where Buddhists were making connections across borders and trying to influence world affairs.

International Buddhism and World Peace

Vietnamese Buddhist revival leaders saw themselves not only as religious reformers and nation builders, but also as part of a global Buddhist movement.[116] From the early 1920s, they were connecting with the wider Buddhist world by engaging with regional print culture, attending international conferences, hosting foreign delegations, and studying abroad.[117] Buddhist communities abroad inspired Vietnamese reformers to strengthen their own institutions and join forces with others to influence the wider world. In May 1951, the founding congress of the GBA declared that it would be joining the World Fellowship of Buddhists (WFB).[118] In PGVN, Thích Nhất Hạnh celebrated the development of global Buddhism as a force for world peace, giving readers a glimpse of the global ethos that would define the later part of his career outside Vietnam. Still, he returned to the theme of national Buddhism—emphasizing that unification at the national level was a necessary step toward participation on the global stage. In November 1956, more than 215 delegates and 500 observers gathered from across Asia, Europe, and the Americas for the fourth international conference of the WFB in Nepal. In that month’s issue of PGVN, Thích Nhất Hạnh provided ample coverage of the conference and emphasized its core message: global Buddhism must help to build the foundation for world peace.[119] Three separate Vietnamese delegations attended this WFB conference, mirroring the divided state of Vietnam and its Buddhist groups: there was the northern delegation led by Lê Đình Thám, the southern delegation led by Thích Tịnh Khiết (president of the GBA), and a delegation representing the Theravada Sangha of Vietnam headed by Thích Bửu Chơn.[120] Phật Giáo Việt Nam reprinted the statement delivered by Thích Minh Châu on behalf of the southern Vietnamese delegation, which spoke to how Buddhism could provide an antidote to the physical and spiritual suffering of the world. It also called on Buddhists to “declare their earnest wish for peace” so that “along with other spiritual faiths, we can build . . . nations that want peace and know how to live with the spirit of wisdom and love.”[121]

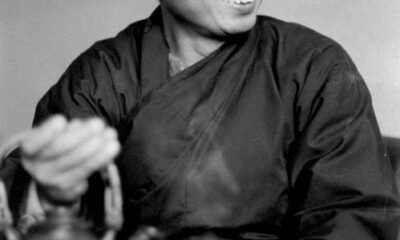

F I G U R E 1 : Delegates at the WFB conference in Kathmandu, Nepal

(November 20, 1956). Photo from the author’s family collection.

While participating in the international Buddhist movement was a source of pride, some Vietnamese reformers could not help but note their lack of progress compared to that of other countries. Lê Văn Định, vice president of the GBA, lamented that Vietnamese Buddhism had fallen behind other countries like China, Japan, Burma, and Ceylon. “We cannot be backward and self-deprecating, simply sitting and watching our neighbors,” he wrote in May 1957. “One [of our neighbors] is opening a large library for holy texts. Another is establishing a university for monks and missionaries. Another is translating scriptures to spread Buddhism all over the West. Yet another is attracting the world’s intellectual elite with its rich Buddhist culture.” These other countries were making great strides in Buddhist development and “meanwhile, what are we doing?” Lê Văn Định asked. “Just performing rituals.”[122] Reiterating Thích Nhất Hạnh’s calls for unification, he went on to say that Vietnamese Buddhists had not achieved much “because we have not yet unified our strength and therefore don’t have the means to do big things.We have used a lot of people’s efforts to achieve little outcome.”[123] The development of Buddhism at the international level was something to celebrate, but it was also a source of shame for Vietnamese reformers who saw their efforts toward national Buddhism as lackluster and slow.

Thích Nhất Hạnh had his own experience with international Buddhism when he traveled to Tokyo in March 1959 as part of the Vietnamese delegation to Japan’s commemoration of the 2,500th anniversary of the Buddha’s enlightenment.[124] This was his first trip abroad; it opened his eyes to the world beyond Vietnam’s borders and inspired him to master the English language.[125] During the trip, because he already knew some English, he delivered a statement on behalf of the Vietnamese delegation which was later printed in PGVN with the title “Buddhism and World Peace.”[126] As the statement shows, Thích Nhất Hạnh believed that the foundational tenets of Buddhism, if followed, would preclude all causes of conflict and war because they are nondogmatic, selfless, and nonviolent. He explained that in Buddhism, all doctrines and theories are treated as part of a larger truth, rather than as oppositional beliefs to be fought over. Buddhism’s core teachings “lean not on unchanging dogma, but rather on wisdom, lived experience, and the real situation of society and the world,” he claimed.[127] Additionally, Buddhism teaches a profound respect for all forms of life and focuses on eliminating the ego, which Thích Nhất Hạnh identified as “the center of all evils” including “greed, hatred, delusion, and conceit.” To support world peace, Thích Nhất Hạnh urged Buddhists to pledge not to kill or “participate directly or indirectly in forces or organizations that support war.”[128] Then, they must patiently and diligently do the long-term work of transforming global society from the ground up. Looking at other major religions, Thích Nhất Hạnh acknowledged that many claim to support peace. He believed, however, that Buddhism was the only religion that had never strayed from its core tenet of compassion, from its founding in the fifth century BCE until the present day.[129] In conceiving of Buddhism as a religion uniquely applicable to the modern world, he followed the example of other reformist Buddhists at international forums dating back to the late nineteenth century. The earliest example of such a claim was at the 1893 World Parliament of Religions, when delegates from Sri Lanka and Japan presented Buddhism as “the religion most suited to modernity.”[130]

With PGVN, Thích Nhất Hạnh fueled the idea of Vietnamese Buddhism as part of a global force that could guide humanity toward peace and stability. While other contributors highlighted the ways in which Vietnam had fallen behind in their development of national Buddhism, Thích Nhất Hạnh wrote about international Buddhism in a positive, aspirational light. He urged PGVN readers to open their eyes and see that, given the urgent global project of peacebuilding, “We no longer have the right to be divided!”[131] It was time for Vietnamese Buddhists to abandon their old ways and join the rest of the world in coming together as a national force.

Conclusion

Under Thích Nhất Hạnh’s leadership, PGVN became, in his words, “the vanguard for the unification of Buddhism.”[132] The tone and content of Thích Nhất Hạnh’s articles on national Buddhism became more pointed as time went on, and he was particularly critical of regional leaders who were invested in maintaining the status quo.[133] “For the past two years, here in the pages of PGVN, we have repeatedly called for the unification of Buddhism . . . But our words seem to fall on deaf ears,” he wrote in May 1958. “Only those who are selfish, who put self before religion, will continue to resist unification.”[134] Going into the third and final year of PGVN’s publication, Thích Nhất Hạnh began calling out specific GBA leaders by their titles, accusing them of silence and inaction. “If you, the key people in our nation’s Buddhist revival, stand idly like this, who shall all the Buddhist faithful rely on?” he asked. “Will they have enough faith to wait for you to fulfill your duty?”[135] In what would be the final issue of the journal, in March 1959, Thích Nhất Hạnh suggested that all local and regional groups be immediately abolished after the next election for the GBA central committee and declared, “We only need those with goodwill toward unification. We don’t need those who are skilled but lack that goodwill.”[136] In the eyes of GBA leaders, Thích Nhất Hạnh may have pushed the issue too far by calling them out individually and trying to accelerate the outright dissolution of their member organizations.

After less than three years in print, PGVN was discontinued. Citing financial constraints, the GBA abruptly ended the magazine’s production after March 1959. Thích Nhất Hạnh believed the real reason they shut down PGVN was to put an end to his relentless advocacy for Buddhist unification and outward criticisms of their leadership.[137] He nevertheless continued to be involved in the southern Buddhist scene into the 1960s, spearheading the establishment of Vạn Hạnh University, continuing to write and publish, and taking the lead on new Buddhist publications like Hải Triều Âm [Sound of the Rising Tide] (1964), Thiện Mỹ [Goodness and Beauty] (1964–1966), and Giữ Thơm Quê Mẹ [Preserving the Fragrance of the Motherland] (1965–1966).[138] He also founded a new organization called the School of Youth for Social Service that trained college-age students in rural development.[1939]

Even though the GBA floundered in its goal of formal unification in the 1950s, Buddhist communities continued to grow at the local and regional levels. They reached the height of their political strength and influence in the early 1960s, when an estimated one million South Vietnamese citizens mobilized as part of the Buddhist movement for religious equality and democratic rule.[140] Immediately following the ousting of President Ngô Đình Diệm in November 1963, Buddhists leaders—many of whom had been involved with the GBA—tried again to unify under a new name: the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBC) [Giáo Hội Phật Giáo Việt Nam Thống Nhất].[141] The UBC remained a major political force through the 1960s, influencing South Vietnamese national politics and international opinion on the war in Vietnam. The organization was plagued by internal division from the beginning, however. Although they agreed on the goal of peaceful unification of Buddhism and the nation, UBC leaders differed in their approaches to organizing and politics, and they formally split into two factions in 1966.[142]

Thích Nhất Hạnh left Vietnam in 1966 to conduct a peace tour in the United States and Europe, hoping to turn the tide of public opinion against the war in his country.[143] His anti-war activities abroad led to his exile for thirty-nine years. Unable to return home, Thích Nhất Hạnh turned to teaching mindfulness in other parts of the world; he published more than one hundred books and established ten retreat centers on four continents. Thích Nhất Hạnh was allowed to return to Vietnam a handful of times after 2005 and lived out the last years of his life in Huế, from October 2018 until January 2022.[144] Although he was received by many as a respected teacher upon his return and his books now sit on the shelves of every major bookstore in Vietnam, after his exile, Thích Nhất Hạnh never again had a formal role in the development of national Vietnamese Buddhism.

Inspired by the Buddhist revival from a young age and witnessing his country’s struggle for independence, Thích Nhất Hạnh set his sights on a modern Vietnamese nation built on a Buddhist philosophical and cultural foundation. As editor in chief of the first national Vietnamese Buddhist magazine from 1956 to 19959, he carried forward the ideals of the revival movement by becoming the foremost champion of modernized and nationally unified Vietnamese Buddhism. Only with a national organization, Thích Nhất Hạnh believed, could Buddhists effectively contribute to nation building efforts and help make their country a peaceful, prosperous, and democratic society. Thích Nhất Hạnh’s writing and editorial work for PGVN reveal that he was a passionate nationalist full of ideas about how organized Buddhism could contribute to Vietnamese independence and international peace in the new world order.

Produced in a time when Vietnam was formally divided and in the throes of decolonization, PGVN also stands as a valuable historical record of Buddhist institutional development and intellectual thought. The rich collection of available twentieth-century Buddhist publications invites more critical studies on the development of modern Vietnamese Buddhism. If given more attention, it will help scholars better understand where figures like Thích Nhất Hạnh came from and where they stand in the broader history of Buddhism and Vietnam in the world.

Notes:

53. Dã Thảo (Thích Nhất Hạnh), “Phật-Giáo với Tinh-Thần Dân-Chủ” [Buddhism and the Spirit of Democracy], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 3 (Oct 1956): 6-10.

54. The original reads “…điều kiện tổ chức cụ thể nhất và hoàn bị nhất của xã-hội lại là quốc-gia.” Dã Thảo, “Phật-Giáo với Tinh-Thần Dân-Chủ,” 9.

55. For a theoretical explanation of the logic of capitalism, modernization, and development in the decolonizing process, see: Walter D. Mignolo and Catherine E. Walsh, On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018). For exceptions to the drive toward nationalism and proposed alternatives to the nation-state, see: Frederick Cooper, Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

56. Dã Thảo, “Phật-Giáo với Tinh-Thần Dân-Chủ,” 6-10.

57. Dã Thảo, “Phật-Giáo với Tinh-Thần Dân-Chủ,” 9.

58. Ibid., 7-8.

59. Ibid., 8.

60. Tâm Quán, “Trả Về,” in Tình Người [Humanity] (Saigon: Lá Bối, 1964).

61. Ibid.

62. Ibid.

63. The original reads: “Thật không có cái gì có tính cách dân chủ hơn cái cảnh tượng một ông vua đến thăm một ông thầy tu và được ông thầy tu mời ăn củ mì.” Ibid.

64. Tâm Quán, “Trả Về.”

65. Ibid.

66. Dã Thảo, “Phật-Giáo với Tinh-Thần Dân-Chủ,” 9-10.

67. âm Quán, “Trả Về.”

68. Soucy, Zen Conquests, 13.

69. Minh Hạnh, “Để đi đến một nền Phật-Giáo dân-tộc” [Toward National Buddhism], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 8 (March 1957): 21-23.

70. Ibid.

71. Thiều Chi, “Chính-Danh” [Definitions], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 8 (March 1957): 42.

72. Ibid.

73. Later, in History of Vietnamese Buddhism (1973), Nhất Hạnh detailed the history of specific Buddhist schools and teachers that contributed to the development of the Vietnamese nation. Nguyễn Lang, Việt Nam Phật Giáo Sử Luận [History of Vietnamese Buddhism] (Saigon: Lá Bối, 1973).

74. Võ Văn Cường, “The Spirit of the Vietnamese People and Buddhism,” Viên Âm 48 (May 1942): 17-25.

75. Minh Hạnh, “Để đi đến một nền Phật-Giáo dân-tộc: Vị Sơ-Tổ của Phật-giáo Việt-Nam” [Toward National Buddhism: The Founding Patriarch of Vietnamese Buddhism], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 9-10 (Apr 1957): 35.

76. Ibid.

77. Minh Hạnh, “Để đi đến một nền Phật-Giáo dân-tộc: Giáo-Lý của Phật-giáo Việt-Nam” [Toward National Buddhism: The Doctrine of Vietnamese Buddhism], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 11 (June 1957): 10-11.

78. Ibid.

79. Paul Demiéville, “Les Religions de l’Orient et de l’Extrême-Orient; Tendances Actuelles,” Encyclopédie Française, quoted in Jerrold Schecter, New Face of Buddha: Buddhism and Political Power in Southeast Asia (New York: Coward-McCann: 1967), 22.

80. In 1966, Nhất Hạnh met with Pope Paul VI and appealed for him to call on Vietnamese Catholics to work with people of other faiths to put an end to the war. He also formed friendships and worked with American Christian leaders Martin Luther King, Jr., Thomas Merton, and Daniel Berrigan to organize in the United States and Europe against the war. “Bonze Asks Pope Paul VI to Go to Vietnam,” Catholic News Service, July 20, 1966; Kevin Cawley, “Vatican Aide Optimistic on Return from Vietnam,” National Catholic Reporter, October 19, 1966; Martin Luther King, Jr., letter to the Nobel Institute, January 25, 1967; Thomas Merton, “Nhất Hạnh Is My Brother,” International Committee of Conscience on Vietnam, June 9, 1966; and Daniel Berrigan and Nhất Hạnh, The Raft Is Not the Shore: Conversations Toward a Buddhist/Christian Awareness (Boston: Beacon Press, 1975).

81. Philip Taylor, “Apocalypse Now? Hoa Hao Buddhism Emerging from the Shadows of War,” Australian Journal of Anthropology Vol. 12 No. 3 (December 2001): 339-354; Hue Tam Ho Tai, Millenarianism and Peasant Politics in Vietnam (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983).

82. Charles Keith, “Annam Uplifted: The First Vietnamese Catholic Bishops and the Birth of a National Church, 1919–1945,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies (2008) 3 (2): 128–171.

83. Ibid., 147-148.

84. Dã Thảo, “Thống Nhất Toàn Vẹn” [Complete Unification] Phật Giáo Việt Nam 9-10 (May 1957): 11-13.

85. “Bản Tuyên Ngôn Thành-lập Tổng-Hội Phật-giáo Việt-Nam.”

86. Phật Giáo Việt Nam 9-10 (Apr-May 1957).

87. Dã Thảo, “Thống Nhất Toàn Vẹn.”

88. Lê Văn Định, “Kỷ niệm ngày thành lập Tổng-hội Phật-giáo Việt-nam” [Remembering the Founding Day of the General Buddhist Association], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 9-10 (May 1957): 6-10.

89. Documents in the Vietnam National Archive II show that Nguyễn Văn Tâm officially recognized the GBA after two years, in 1953, while GBA Vice President Lê Văn Định claimed it took four years in his PGVN article “Kỷ niệm ngày thành lập Tổng-hội Phật-giáo Việt-nam.” According to Cousin-Thorez, Nguyễn Văn Tâm, the fourth ruler of the State of Vietnam from June 1952 to January 1954, delayed granting recognition to the GBA because he believed it was infiltrated by communists and that it was domineering toward other Buddhist organizations. Cousin-Thorez, 110.

90. Cousin-Thorez, 111; Lê Văn Định, “Kỷ niệm,” 6-10.

91. Lê Văn Định, “Kỷ niệm,” 8-9.

92. Trọng Đức, “Vì sao cần thống-nhất Phật-giáo Việt-nam” [Why We Need Vietnamese Buddhist Unification], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 25-26 (Sept-Oct 1958): 26-30.

93. Ibid.

94. Ibid.

95. Ibid.

96. Trọng Đức, “Vì sao cần thống-nhất Phật-giáo Việt-nam,” [Why We Need to Unify Vietnamese Buddhism] Phật Giáo Việt Nam 27 (Jan 1959): 12-16.

97. Trọng Đức, “Vì sao cần thống-nhất Phật-giáo Việt-nam,” [Why Vietnamese Buddhist Unification is Needed] Phật Giáo Việt Nam 27 (Jan 1959): 12-16.

98. Soucy, Zen Conquests, 14-15.

99. Thiều Chi, “Vấn-Đề Hoằng-Pháp” [The Issue of Preaching], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 13 (Aug 1957): 17-21.

100. Thích Thiện Hoa mentioned a handful of monks who were on board with the GBA preaching program including Thích Thiện Minh, Thích Thiện Siêu, Thích Trí Quang, and Thích Mật Nguyện. Ibid.

101. Ibid.

102. Thiều Chi, “Vấn-Đề Nghi-Lễ” [The Issue of Rituals], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 15 (Oct 1957): 17-21.

103. Ibid.

104. Thích Tâm Châu, “Kế hoạch thực hiện Thống-nhứt nghi-lễ” [The Plan to Realize Unification of Rituals], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 25-26 (Sept-Oct 1958): 36-38.

105. Thiều Chi, “Vấn-Đề Nghi-Lễ.”

106. Ibid.

107. Thích Tâm Châu, “Kế hoạch thực hiện Thống-nhứt nghi-lễ.”

108. Thích Thiện Hòa, recommendation letter, Thích Nhất Hạnh’s Application for Fellowship, Scholarship, or other Educational Exchange Grant in the United States of America, 1 April 1961, Princeton Theological Seminary; Thầy Trí Không, Những Năm Tháng Theo Thầy (Ho Chi Minh City: Phanbook/Hồng Đức, 2022), 44-45; Làng Mai, 51.

109. Sister True Dedication and Sister Định Nghiêm, eds., “Thich Nhat Hanh: Extended Biography.”

110. Dã Thảo, “Vấn-Đề đào-tạo Tăng-tài” [The Issue of Monastic Training], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 11 (June 1957): 15-19.

111. Ibid., 16.

112. Ibid., 18.

113. Ibid., 18-19.

114. Vạn Hạnh University was one of three proposals Nhất Hạnh brought to the Unified Buddhist Church leadership after his return to Vietnam in January 1964, and was the only plan they approved. The other two plans were to call on people in the north and south to work together to stop the war, and to build a center for social work that would send people to help the poor in the countryside based on Buddhist nonviolence. Làng Mai, 105-106.

115. Thich Minh Chau, “Opening Speech Given by the Rector of Vạn Hạnh University, at the Vietnam Forum, January 9, 1974,” Vạn Hạnh Bulletin 6, no. 1 (March 1974): 31.

116. In 1938 the Northern Buddhist Association published a book called Buddhist Studies Around the World [Hoàn-Cầu Phật Học] that shows a high degree of familiarity with the global “new movement” for Buddhism as well as developments in Buddhist studies across Asia, Europe, and the United States. DeVido, “Buddhism for this World,” 272.

117. Evidence of these activities can be found in the regional Buddhist journals available through Huệ Quang Library in Ho Chi Minh City.

118. “Hội Nghị Thống Nhất Phật Giáo Việt Nam” [Buddhist Unification Conference], Viên Âm 104 (8 April 1951): 3-4.

119. P.G.V.N., “Phật-giáo Thế-giới với nền Hòa-bình Nhân-loại” [Global Buddhism and Peace for Humanity] Phật Giáo Việt Nam 4 (Nov 1956): 3-5.

120. According to Thích Minh Châu, the three delegations were: the Northern Vietnamese delegation with Lê Đình Thám as the lead and Thích Trí Đô as an interpreter; the Southern Vietnamese delegation including Thích Tịnh Khiết, Thích Huệ Quang, Thích Minh Châu, and Trần Thanh Hiệp; and a third delegation led by Thích Bửu Chơn with four lay women and one layman. Thích Minh Châu, “Phong Trào Phật-giáo” [The Buddhist Movement] Phật Giáo Việt Nam 7 (Feb 1957): 23-26.

121. Thích Minh Châu, “Phong Trào Phật-giáo,” 23-26.

122. Lê Văn Định, “Kỷ Niệm,” 10.

123. Ibid.

124. Nhất Hạnh, Application for Fellowship, Scholarship, or other Educational Exchange Grant in the United States of America, 1 April 1961, Princeton Theological Seminary; Trí Không, 199; Làng Mai, 72-73. According to Thích Trí Không, the Vietnamese Buddhist delegation to Tokyo from 27-31 March 1959 included: Thích Thiện Hoa (Commissioner of Preaching for the GBA), Thích Nhất Hạnh (Editor of Phật Giáo Việt Nam), Thích Tâm Châu (Commissioner of Ceremonies for the GBA), and Thích Mật Hiển (member of the monastic sangha of the central region).

125. Thích Trí Không recalls that after returning from Japan, Nhất Hạnh was keen on mastering the English language so that he could someday conduct research in the United States. Trí Không, 206.

126. Làng Mai, 72-73; P.G.V.N., “Đạo Phật và nền Hòa-bình Thế-Giới” [Buddhism and World Peace], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 28 (March 1959): 16-18.

127. P.G.V.N., “Đạo Phật và nền Hòa-bình Thế-Giới,” 17.

128. Ibid.

129. Ibid.

130. Anna Sun, Confucianism as a World Religion (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 60-61, cited in Soucy, Zen Conquests, 17.

131. P.G.V.N., “Phật-giáo Thế-giới,” 5.

132. “Phật Giáo Việt Nam nguyệt san qua năm thứ hai,” [Vietnamese Buddhism Magazine Turns Two] Phật Giáo Việt Nam 24 (15 August 1958): 5-7.

133. Dã Thảo, “Thống Nhất Toàn Vẹn.”

134. P.G.V.N. “Lại Vấn-đề Thống-nhất Phật-giáo” [Again the Issue of Buddhist Unification] Phật Giáo Việt Nam 20-21 (Apr-May 1958): 3-6.

135. P.G.V.N. “Làm thế nào để giữ vững tín tâm của Phật-tử” [How We Can Maintain the Faith of the Buddhists] Phật Giáo Việt Nam 22 (June 1958): 3-7.

136. Trọng Đức, “Cần thống-nhất thật sự Phật-giáo Việt-nam” [The Need to Truly Unify Vietnamese Buddhism], Phật Giáo Việt Nam 28 (March 1959): 27-31.

137. Nhất Hạnh himself noted the lack of financial resources for PGVN from the start, as stated in “Phật Giáo Việt Nam nguyệt san qua năm thứ hai.” Still, he maintained the primary reasons for the journal’s shutdown were more personal. Nhất Hạnh, Nẻo Về Của Ý (Hanoi: Hồng Đức, 2017), 17.

138. Hải Triều Âm (1964), General Sciences Library, Ho Chi Minh City; Huỳnh Như Phương, introduction to reprinted volumes of Giữ Thơm Quê Mẹ (HCMC: Thư Viện Huệ Quang, 2018); Thiện Mỹ (1964-1966), General Sciences Library, Ho Chi Minh City.

139. For more this, see: Sister Chan Khong, Learning True Love: Practicing Buddhism in a Time of War (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 2007); Adrienne Minh-Châu Lê, “Buddhist Social Work in the Vietnam War: Thích Nhất Hạnh and the School of Youth for Social Service” in Republican Vietnam, 1963–1975: War, Society, Diaspora, eds. Trinh M. Luu and Tuong Vu (University of Hawai’i Press, 2023), chapter 6.

140. “The Buddhists in South Vietnam,” US Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Current Intelligence, Special Report, SC No. 00598/63A (June 28, 1963), Central Intelligence Agency-Electronic Reading Room.

141. Records of meetings to establish the Unified Buddhist Church, 13-15 December 1963, folder 29372, Phủ Thủ Tướng Việt Nam Cộng Hoà, Vietnam National Archives II, Ho Chi Minh City.

142. Documents on the division of the Unified Buddhist Church, October 1966-August 1967, folder 29858, Phủ Thủ Tướng Việt Nam Cộng Hoà, Vietnam National Archives II, Ho Chi Minh City.

143.

Bryce Nelson, “Buddhist Monk Pleads Here for End to War,” Washington Post, June 4, 1966; Max Zahn, “Talking Buddha, Talking Christ,” Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, September 30, 2015.

144. Nhất Hạnh returned to Vietnam in 2005, 2007, 2017, and 2018. “Plum Village Practice in Vietnam,” Plum Village, January 3, 2014, https://plumvillage.org/blog/monastic/plum-village-vietnam-background; “Thay Arrives in Vietnam,” Plum Village, August 29, 2017, https://plumvillage.org/news/thich-nhat-hanh-arrives-in-vietnam; Nhất Hạnh, “English Translation of Thay’s letter to Root Temple Descendants, October 2018,” October 26, 2018, https://plumvillage.org/letters-from-thay/tnh-letter-to-root-temple-descendants.

You may like

-

Toward National Buddhism: Thích Nhất Hạnh on Buddhist Nationalism and Modernity in the Journal Phật Giáo Việt Nam, 1956-1959 (Part 1)

-

A History of Legal Thought in Vietnam, 1945–1956 – Part 3: The Attack of the Communists

-

In Search of What I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải (Part 4)

-

Interview with Venerable Thich Khong Tanh: The tactics of the Vietnamese authorities on religion are: repression, division, isolation, and enticement

Reflections on New Era of National Rise by Vietnam General Secretary Tô Lâm

Of Space & Place: On the Nationalism(s) of Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s “Our Ghosts Live in the Future”

Postwar Music In Vietnam And The Diaspora

Translation: The Decision in 2013 of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Certain Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform

Thủ Đức Demonstration High School: A Modern Educational Policy and Teaching Method of the Republic of Vietnam

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years agoRethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

-

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years agoDeporting Vietnamese Refugees: Politics and Policy from Bush to Biden (Part 1)