Politics & Economy

Toward National Buddhism: Thích Nhất Hạnh on Buddhist Nationalism and Modernity in the Journal Phật Giáo Việt Nam, 1956-1959 (Part 1)

Published on

Editor’s Note: The following article was published in the Journal of Vietnamese Studies, Vol. 19, Issue 1. The study details the life of Thích Nhất Hạnh and his involvement with Buddhist nationalism. Because of the importance of this topic, the article will be reproduced here in full, split into two parts. Part 1 consists of the first three sections of the article. No content changes have been made.

Thích Nhất Hạnh was not widely known as a Vietnamese nationalist in his lifetime. Popular media narratives focus on his life after exile and depict him as a lone global visionary of mindfulness and engaged Buddhism.[1] Exiled and labeled a national traitor because of his opposition to the war in 1966, he published books in more than forty languages and opened retreat centers on four continents, not tying his activities to any one place. Despite his worldwide reputation, few studies have been done on Thích Nhất Hạnh’s life, and his historical significance remains an open question. This article addresses the dearth of rigorous scholarship on Thích Nhất Hạnh by exploring a significant yet understudied part of his intellectual life that reveals his deep commitment to Vietnamese Buddhism and the Vietnamese nation starting in the late 1950ss.

In contrast to the globalist image he cultivated after his exile, Thích Nhất Hạnh was once the most outspoken Buddhist nationalist in Vietnam. This article provides an in-depth examination of his work as editor in chief of the first national Vietnamese Buddhist magazine, Phật Giáo Việt Nam (PGVN) [Vietnamese Buddhism], from 1956 to 1959. It also contextualizes Thích Nhất Hạnh as both a product and a torchbearer of the Vietnamese Buddhist revival movement [chấn hưng Phật Giáo] that began around the time of his birth. In more than one hundred articles that he wrote for PGVN, Thích Nhất Hạnh rode the intellectual waves of the Buddhist revival—exploring modernity, nationalism, and globalism in relation to Buddhism. His writings were clearly influenced, in both style and substance, by the reformist publications of the 1930s–1940s, which he read as a novice. Yet he was distinct from earlier reformists in that he wrote in support of a specific nationalist agenda. Reformist leaders of the earlier generation wrote broadly about the spirit of Buddhism in Vietnamese nationalism while organizing only at the regional level, within their northern, central, and southern Buddhist associations. In contrast, Thích Nhất Hạnh made it his mission to convince fellow Buddhists to consolidate themselves into a truly national organization. This study contends that Thích Nhất Hạnh’s unique contribution to the development of Vietnamese Buddhism in the 1950s lies in his relentless advocacy for a centralized, national Buddhist organization. He believed this type of organization was key to Buddhist nation-building efforts and that it would help bring peace and democracy to Vietnam.

Existing scholarship on Thích Nhất Hạnh focuses on his life during and after the 1960s, when he began speaking and publishing in English and became known as a peace activist in exile. Most studies from the late 1970s to the early 2000s rely heavily on English-language accounts by Thích Nhất Hạnh himself or by his close collaborators, like Sister Chân Không, mostly taking them at face value.[2] Few have looked into Thích Nhất Hạnh’s earlier life and how he was influenced by the early twentieth-century Buddhist revival. Two authors who have acknowledged this historical connection are Elise Anne DeVido and Alexander Soucy, who both emphasize the revival movement’s influence on his philosophy of engaged Buddhism.[3] No scholars have provided a close examination of his extensive writings for PGVN and their nationalist inclinations. The dearth of studies on the pre- 1960s period of Thích Nhất Hạnh’s life can be attributed to the lack of biographical sources on Thích Nhất Hạnh as well as the necessity of Vietnamese language skills to parse through the journals of that time. It is also worth noting that Thích Nhất Hạnh does not factor into major studies on the so-called “Buddhist crisis” of 1963–1966, which has led some to 10 L Ê question his importance in the South Vietnamese Buddhist community during the war.[4] Additionally, no scholars have explored the polarized opinions about Thích Nhất Hạnh within the Vietnamese diaspora since 1975. Only one author has written about the aims and significance of his 2005 return to Vietnam after thirty-nine years in exile.[5] With just a handful of chapters and articles—and no book-length academic works—on Thích Nhất Hạnh, scholars have barely begun to critically explore his role in Vietnamese and Buddhist history.

This study focuses on the earlier period of Thích Nhất Hạnh’s life, before he gained a following in the 1960s and turned his attention abroad. It balances existing hagiographical narratives with concrete evidence and critical analysis of his life and work in historical context. Research for this article was done primarily with Vietnamese sources, including reformist Buddhist journals of the 1930s–1940s and the twenty-eight issues of PGVN, published from August 1956 through March 1959.[6] Additionally, I consult newly available Vietnamese works, including the book-length biography of Thích Nhất Hạnh attributed to his monastic sangha, titled Đi gặp mùa xuân [Meeting the Spring], and the memoir of a monk named Thích Trí Không, who was Thích Nhất Hạnh’s student and de facto attendant in the late 1950s.[7] These sources provide a clear narrative of the lesser-known parts of Thích Nhất Hạnh’s life, but since they do not provide adequate citations or evidence, I corroborate their claims with other sources where possible.

This article is organized in five parts. It starts with a brief biographical introduction to Thích Nhất Hạnh’s early life, showing how his ideology and intellectual trajectory was shaped by the Buddhist revival movement during his novice years in Huế. It then follows Thích Nhất Hạnh to the southern Buddhist scene in the 1950s, tracing his development as a scholar and writer in Sài Gòn and Đà Lạt, which led him to the role of editor in chief of PGVN. The subsequent three sections explore his writings on democracy and nationalism; on the creation of a national Buddhist organization; and finally on international Buddhism and world peace.

Thích Nhất Hạnh’s Early Life

Thích Nhất Hạnh was born on October 11, 1926, in central Vietnam as the fifth of six children in a privileged Buddhist family.[8] He was given the name Nguyễn Xuân Bảo at birth, which was changed to Nguyễn Đình Lang when he enrolled in school at age four.[9] His father, Nguyễn Đình Phúc, was a native of Huế and an official under the French imperial administration. His mother, Trần Thị Dĩ, was from Quảng Trị Province. Until age five, Thích Nhất Hạnh lived with his parents, siblings, and extended family in his paternal grandmother’s house in Huế—it was a large home with a courtyard, lotus pond, and bamboo grove. His fond childhood memories include strolling around the courtyard, playing with snails, and enjoying the cakes his mother would bring home from the market. Sometime around 1930, his father was assigned to work on land reclamation up north in the Nông Cống district of Thanh Hoá Province, and a year later, the rest of the family joined him there.

Thích Nhất Hạnh began to develop an interest in Buddhism during his pre-teen years in Thanh Hoá. The first strong impression he had of the religion came through the Buddhist magazines that his elder brother, Nho, would bring home. He recalled being captivated by the image of the Buddha sitting on the cover of Đuốc Tuệ [Torch of Wisdom], the magazine of the Northern Buddhist Association [Hội Phật Giáo Bắc Kỳ]. At age 12, looking at that image, he was inspired to be “someone who embodied calm, peace, and ease” just like the Buddha.[10] He held onto this idea through his early teenage years, though he did not yet know what being a Buddhist monk entailed. His brother Nho was the first among his siblings to become a monk.[11] In 1942, at age 16, Thích Nhất Hạnh received permission from his parents to follow in his brother’s footsteps and return to Huế to pursue a monastic life at Từ Hiếu temple under Master Thích Chân Thật. After three years of aspirant training, he was fully ordained as a novice with the Dharma name Phùng Xuân and was sent to the nearby Báo Quốc Institute to further his studies.[12]

Thích Nhất Hạnh entered monastic life amid the anti-colonial struggle and the Buddhist revival in Vietnam. Living and studying in Huế from 1942 to 1949, he was steeped in ideas about modernized Buddhism and how it could contribute to the building of an independent Vietnamese nation. It is impossible to understand Thích Nhất Hạnh’s later work without a grasp of the revival movement that defined his first seven years of monastic life. As the following section will show, it was the literature of the Buddhist revival movement—against the backdrop of the struggle for national independence—that instilled in Thích Nhất Hạnh the progressive spirit and nationalist sentiment he later exhibited as editor in chief of PGVN.

Thích Nhất Hạnh’s Novice Years: A Student of the Buddhist Revival Movement

The Buddhist revival was a phenomenon that unfolded across Asia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Led by Chinese reformers, it spread with the help of modern publishing as well as international networks that had formed through long-established regional trade routes.[13] Revival leaders sought to make their religion more in tune with the needs and attitudes of modern society. This meant making Buddhist philosophy more rational and engaged with the real world; it also meant forming regional and national organizations that would enable Buddhists to work with governments and within the international system. Importantly, in places that had suffered Western colonialism and encroachment, Buddhism was held as proof of a precolonial national identity and long history of intellectualism, culture, and values that were distinctly Asian.[14] Through the revival movement, Buddhism became entwined with modernization and nation building in Asia.

Major trends in the Vietnamese revival movement can be traced through the regional Buddhist journals that sprung up in the 1930s, including the Tonkinese Đuốc Tuệ (1935–1945), the Annamese Viên Âm [Complete Sound] (1933–1952), and the Cochinchinese Từ Bi Âm [Sound of Compassion] (1932–1945).[15] Particularly influential to the Vietnamese revival was the Chinese reformist monk Taixu [Thái Hư], whose articles were translated and propagated through these quốc ngữ journals.[16] Vietnamese reformers adopted Taixu’s ideas on reforming Buddhist institutions, educating monastics and lay people, and promoting humanistic or worldly Buddhism [nhân gian Phật Giáo]—a type of Buddhism in which practitioners address real-world suffering through education, charity, and social work rather than focusing exclusively on isolated spiritual practices like meditation and chanting. The Vietnamese revival prompted the construction of urban temples and Buddhist institutes, the founding of lay associations, the organization of lectures for the masses, and the creation of a lively print culture of Buddhist books, journals, and pamphlets.[17] As DeVido wrote, these reformist initiatives would serve as “the organizational and conceptual foundation for Vietnamese national Buddhism.”[18] They also shaped the intellectual trajectory and ideology of the next generation of Buddhists, including Thích Nhất Hạnh.

Thích Nhất Hạnh was deeply influenced by Buddhist revival movement thinkers, beginning in his novice years. In September 1947 he enrolled at the Báo Quốc Institute, a reformist school that had been established in 1932 as the center for Buddhist studies in Huế.[19] There, he and his classmates often read the journals produced by revival leaders and were even inspired to start their own magazine, Tiếng Sóng [Sound of the Waves], which was modeled after Taixu’s journal Hai Chao Yin [Sound of the Tide] in China.[20] Comparing Thích Nhất Hạnh’s later writings to articles by prominent Vietnamese revival leaders like Trí Hải, Nguyễn Trọng Thuật, and Lê Đình Thám, it is clear that his intellectual approach and many of his ideas came from them. He adopted the practical and straightforward style of these authors, often guiding readers to use their own reasoning and lived experience to judge the validity of Buddhist concepts. He shared their desire to speak to issues of the modern world, to abolish superstitions, and to create an orthodoxy based on the teachings of the historical Buddha.[21] He also embraced a narrative that they advanced, suggesting that Buddhism had two thousand years of history in Vietnam and that it could serve as a basis for a strong, modern independent nation.[22]

Thích Nhất Hạnh and others in his generation absorbed the ideas of the Buddhist revival and saw themselves as responsible for bringing them to life in Vietnam. During his training in Huế, Thích Nhất Hạnh noted a generational difference in the community around him. The elder monks did not concern themselves with current affairs, but, Thích Nhất Hạnh wrote, “[I and the other novices] had to think about complicated matters such as how to renew Buddhism, and how to bring Buddhism back into everyday life like it had been during the Lý and Trần dynasties. We had to think about our studies, the practice, taking exams, and how to reorganize the Buddhist congregation.”[23] While the older generation was able to focus on their internal spiritual lives, his generation looked outside and saw a world full of problems that they needed to address. “We had been invaded by the social 14 L Ê realities of our time,” he wrote.[24] Indeed, Thích Nhất Hạnh’s early monastic life was infiltrated by war and the struggle for national independence. At one point, he and the other monks of Từ Hiếu were forced to evacuate to the mountains, returning several months later to discover the temple’s roofs and walls dotted with bullet holes.[25] He witnessed French soldiers raiding temples for supplies and had monastic teachers and friends who were killed or disappeared as suspected supporters of the anti-colonial resistance.[26] Coming of age amid the struggle for independence, Thích Nhất Hạnh’s sense of injustice and nationalist sentiment grew strong, though it was not always clear what form his nationalism would take.

There was a time, likely during his novice years in the 1940s, when Thích Nhất Hạnh was tempted to become a communist.[27] He reflected on this in a talk in 2003: “I saw that in the Buddhist community people talked a lot about serving living beings, but they didn’t have any practical methods to help the country, which was under foreign rule. . . . I saw that the communists were really trying to do something, and they were ready to die for the sake of humanity.”[28] He ultimately decided not to join the communists, he explained, because he realized that being a member of the party meant obeying orders and potentially being forced to kill his fellow countrymen. “I was saved,” he said, by the realization that “violent revolution was not my path.”[29] Thích Nhất Hạnh remained a monk and became more invested in the movement to update Buddhism and restore its core teachings, believing that this could “offer a nonviolent path to peace, prosperity, and independence from colonizing powers.”[30] He committed himself to nonviolent revolution in the form of modern Buddhist nationalism.

The first step toward modernizing Vietnamese Buddhism, Thích Nhất Hạnh decided, was to broaden his own education. While he enjoyed his time as a student at the Báo Quốc Institute, he was unsatisfied with the curriculum, which, during that time, focused almost entirely on Buddhist sutras and literature. [31] He wanted to expand his studies tomath, science, philosophy, economics, and foreign languages—subjects he believed were essential to understanding and influencing themodern world. In the spring of 1949, at age 22, he decided to withdraw from Báo Quốc along with two friends. The three novices wrote a farewell letter to the directors of the institute and boarded a boat in Đà Nẵng, hoping to find their own way as Buddhist monks in the modern era. During their journey south to Sài Gòn, they adopted new names that reflected their aspiration to put Buddhism in action. This was when novice Phùng Xuân took on the name Nhất Hạnh, meaning one action.[32]

Intellectual Life in Southern Vietnam: Thích Nhất Hạnh’s Path to PGVN

In his first decade in southern Vietnam, from 1949 to 1959, Thích Nhất Hạnh immersed himself in the growing worlds of education and publishing. Splitting his time between the bustling city of Sài Gòn and the mountain region of Đà Lạt, he steadily built his reputation as a scholar, teacher, and writer.[33] This section examines Thích Nhất Hạnh’s work and studies in the south, which led him to become editor in chief of PGVN in 1956. Through his activities, we get a sense of the bustling and somewhat scrappy Buddhist scene in 1950s southern Vietnam. It was there that Thích Nhất Hạnh found the networks, institutions, and platforms that would enable him to carry forward the ideals of the Buddhist revival by becoming the leading voice on national Buddhism.

After arriving in Sài Gòn in 1949, Thích Nhất Hạnh found housing at various Buddhist temples and enrolled in private classes for English, math, physics, chemistry, literature, and history.[34] He received full monastic ordination in October 1951 at Ấn Quang temple—the place he described as his spiritual and intellectual home.[35] After earning his formal high school degree in Đà Lạt in 1953, he returned to Sài Gòn to help develop the Ấn Quang Buddhist Institute.[36] From 1953 to 1957, Thích Nhất Hạnh studied Buddhist philosophy and Chinese Tripitaka texts at Ấn Quang, becoming an assistant lecturer and then professor under the supervision of Thích Thiện Hoà.[37] He taught courses on the history of Buddhism, Buddhist literature, and Vietnamese, and he encouraged his students to learn French by listening to the radio every night.[38] While studying and teaching at Ấn Quang, Thích Nhất Hạnh purportedly enrolled at the newly established Sài Gòn University under his birth name, Nguyễn Xuân Bảo, and earned a bachelor’s degree in French and Vietnamese literature.[39] There is no known paper trail of Thích Nhất Hạnh’s studies at Sài Gòn University.[40] There is, however, a public record of his intellectual life from 1949 to 1955 that demonstrates a higher level of knowledge and influence than his formal educational record suggests. In these six years, Thích Nhất Hạnh published seven books, including three poetry collections and four nonfiction works on Buddhist philosophy and engaged Buddhism.[41] He also founded and managed three short-lived magazines—Hướng Thiện [Direction of Goodness], Liên Hoa [Lotus], and Sen Hồng [Pink Lotus].[42] In 1955, Thích Nhất Hạnh wrote a ten-part series called “Buddhism through New Perspectives” [Đạo Phật qua nhận thức mới] for the dissident newspaper Dân Chủ [Democracy], which explored Buddhist concepts in relation to the modern world.[43] The articles were apparently so well received that they were republished by the Southern Vietnamese Buddhist Study Association as a book with a preface by the association’s president, Mai Thọ Truyền.[44] Thích Nhất Hạnh’s publications show that in just a few years, he went from being an unknown novice monk to an accomplished author and public voice on modern Buddhism.

As Thích Nhất Hạnh was starting to build his reputation as an intellectual, Buddhist leaders took a significant step toward the long-held ideal of national Buddhist unification. The General Buddhist Association (GBA) [Tổng Hội Phật Giáo Việt Nam] was established on May 9, 1951, after a four-day congress at Từ Đàm pagoda in Huế with fifty-one representatives from all three regions of the country.[45] The GBA’s mission, as stated in its founding charter, was to unify Vietnamese Buddhism so that “the religion of supreme compassion” could “extinguish the fire of anger and delusion” and “build peace for mankind.”[46] In 1956, the GBA launched its official magazine, PGVN, reflecting the organization’s aspiration for national Buddhist unification. Thích Nhất Hạnh was given the role of editor in chief, despite being only 29 years old and fully ordained as a monk for less than five years.[47] The magazine was published at Ấn Quang temple for two and a half years, from August 1956 through March 1959, with a total of twenty eight issues.[48] While its precise circulation is unknown, PGVN’s readership can be roughly estimated using membership numbers of the GBA, which stood at about 360,000 registered members plus 58,500 “active sympathizers” in 1959.[49] The stated mission of PGVN was to keep GBA members informed and encourage everyone to come together to strengthen Vietnamese Buddhism for the benefit of the people and nation. Thích Nhất Hạnh ensured the fifty or so pages of every issue were filled, often by writing a large portion of the content himself under different pen names.

Over the twenty-eight issues of PGVN, Thích Nhất Hạnh penned at least 113 pieces under ten pseudonyms plus his own name, accounting for roughly 40 percent of the articles overall.[50] Each of his pen names focused on different topics: Thạc Ðức wrote about Buddhist literature and philosophy; Hoàng Hoa and Minh Thư wrote fables and short stories; Tâm Kiên wrote modern folk poetry; Tâm Quán wrote about monastic novice life; Minh Hạnh wrote about world literature, philosophy, and national Buddhism; Tuệ Uyển wrote about Buddhist methodology; Thiều Chiwrote about Buddhist unification; Dã Thảo wrote about modern Buddhism and its institutions; and Phương Bối wrote about Buddhist youth.[51] Under his own name, Thích Nhất Hạnh published only poetry, with themes of nature and peace. Many of the themes in Thích Nhất Hạnh’s PGVN pieces appeared in earlier journals of the Buddhist revival—including selfreliance, anti-superstition, collective responsibility, and Vietnamese national and cultural identity. The most frequently recurring topic in Thích Nhất Hạnh’s articles, and the one that set him apart from his intellectual predecessors, was the national unification of Vietnamese Buddhism.

In Thích Nhất Hạnh’s own words, he used his position as editor of PGVN “to raise awareness about humanist and nationalist Buddhism.”[52] Indeed, during the years PGVN was in circulation, he was the single most outspoken proponent of a centralized, national Buddhist organization in Vietnam. Believing national Buddhism would pave the way to peace and democracy, he used his position as editor in chief to publish extensively on why Buddhism was the right ideological foundation for Vietnam.[53]

…

Notes:

- For example, see: Supriya Batra and Bryan Walsh, “The Monk Who Taught the World Mindfulness Awaits the End of This Life,” TIME (4 February 2019): https://time.com/5511729/monk-mindfulness-art-of-dying; Seth Mydans, “Thich Nhat Hanh, Monk, Zen Master and Activist, Dies at 95,” New York Times (22 January 2022): https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/21/world/asia/thich-nhat-hanh-dead.html.

- See for example: Marjorie Hope and James Young, “The Third Way: Thich Nhat Hanh and Cao Ngoc Phuong,” in Hope and Young, The Struggle for Humanity: Agents of Nonviolent Change in a Violent World (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1977); Sallie B. King, “Thich Nhat Hanh and the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam: Nondualism in Action,” in Christopher Queen and Sallie King (eds.), Engaged Buddhism: Buddhist Liberation Movements in Asia (Albany: SUNY Press, 1996), 321-363; Patricia Hunt-Perry and Lyn Fine, “All Buddhism is Engaged: Thich Nhat Hanh and the Order of Interbeing,” in Christopher S. Queen (ed.), Engaged Buddhism in the West (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000).

- Elise Anne DeVido, ““Buddhism for this world”: The Buddhist Revival in Vietnam, 1920 to 1951, and Its Legacy,” in Philip Taylor (ed.), Modernity and Re-enchantment: Religion in Post-revolutionary Vietnam (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2007), 250-296 and “The Influence of Chinese Master Taixu on Buddhism in Vietnam,” Journal of Global Buddhism 10 (2009), 413-458; Alexander Soucy, “Thích Nhất Hạnh in the Context of the Modern Development of Vietnamese Buddhism,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion (2021) and Zen Conquests: Buddhist Transformations in Contemporary Vietnam (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2022), 6-7.

- Here I am referring to Robert J. Topmiller, The Lotus Unleashed: The Buddhist Peace Movement in South Vietnam, 1964-1966 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002); and Edward Miller, “Religious Revival and the Politics of Nation Building: Reinterpreting the 1963 ‘Buddhist crisis’ in South Vietnam,” Modern Asian Studies 49, No. 6 (November 2015): 1903-1962. One study on this period that does feature Nhất Hạnh prominently is Phạm Văn Minh’s Vietnamese Engaged Buddhism: The Struggle Movement of 1963-1966 (Westminster: Văn Nghệ, 2002).

- John Chapman, “The 2005 Pilgrimage and Return to Vietnam of Exiled Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh,” in Modernity and Re-enchantment, 297-341.

- Reprints of twentieth-century Buddhist journals are now available through Thư Viện Huệ Quang [Hue Quang Library] in Ho Chi Minh City.

- Tăng Thân Làng Mai, Đi Gặp Mùa Xuân [Meeting the Spring] (Hanoi: Thế Giới, 2022); Thầy Trí Không, Những Năm Tháng Theo Thầy [The Years and Months Following My Teacher] (Ho Chi Minh City: Phanbook/Hồng Đức, 2022).

- There are conflicting accounts of his birthplace, but most commonly he is said to have been born in Huế. The biographies published by his monastic sangha say he was born in Huế, while his 1961 application to study at Princeton Theological Seminary as well as 1963 South Vietnamese government records say he was born in Đà Lạt. Làng Mai, Đi Gặp Mùa Xuân, 12; True Dedication and Định Nghiêm, “Thich Nhat Hanh: Extended Biography”; Nhất Hạnh, Application for Fellowship, Scholarship, or other Educational Exchange Grant in the United States of America, 1 April 1961, Princeton Theological Seminary; Memo of the Interior Minister on Nhất Hạnh’s activities abroad, 5 September 1963, Phủ Tổng Thống Đệ Nhị Cộng Hoà, folder 4218, Vietnam National Archives II, Ho Chi Minh City.

- The following biographical details are based on Làng Mai, Đi Gặp Mùa Xuân, 12-15 and “Thich Nhat Hanh: Extended Biography” unless otherwise noted.

- According to Đi Gặp Mùa Xuân, the specific magazine that caught his eye was issue 104 of Đuốc Tuệ. This means Nhất Hạnh was twelve years old, since that issue was printed in March 1939. The quote here is from “Thich Nhat Hanh: Extended Biography,” which estimates this “pivotal moment” happened around age nine; this is inconsistent with the date of the magazine cited in Đi Gặp Mùa Xuân.

- Upon ordination, Nho received the Dharma name Thích Giải Thích. Làng Mai, 15.

- “Thich Nhat Hanh: Extended Biography” explains that Phùng Xuân means “meeting the spring.”

- Elise Anne DeVido, “Buddhism for This World,” 259-262.

- DeVido, “Buddhism for This World,” 256. For more on the development of non-European nationalism and a similar case of Hindu nationalism, see: Partha Chatterjee, The Nation and its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

- Đuốc Tuệ was published by the Northern Buddhist Association [Hội Phật Giáo Bắc Kỳ]; Viên Âm was produced by the Annamese Buddhist Study Association [Hội An Nam Phật Học]; and Từ Bi Âm was printed by the Southern Buddhist Research Association [Hội Nam Kỳ Nghiên Cứu Phật Học]. Reprints of these journals are available through Thư Viện Huệ Quang [Hue Quang Library] in Ho Chi Minh City.

- The first to translate Taixu’s writings into quốc ngữ and distribute them throughout Vietnam were the southern monks Khánh Hoà and Thiện Chiếu. Also notable for spreading Taixu’s writing was his Vietnamese monastic disciple Trí Hải. Nguyen Tai Thu, ed., History of Buddhism in Vietnam (Hanoi: Social Sciences Publishing House, 1992), 388-391; DeVido, “Buddhism for This World,” 265-267.

- DeVido, “Buddhism for This World,” 252; “The Influence of Chinese Master Taixu on Buddhism in Vietnam” Journal of Global Buddhism 10 (2009): 413–458. For more on the role of Buddhist print culture, see: Shawn Frederick McHale, Print and Power: Confucianism, Communism, and Buddhism in the Making of Modern Vietnam (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2004).

- DeVido, “The Influence of Chinese Master Taixu on Buddhism in Vietnam,” 426.

- Niên Trưởng, Trụ Trì Tổ Đình Từ Hiếu, Lễ Tâm Tang Thiền Sư Thích Nhất Hạnh (Hanoi: Thế Giới, 2022), 10.

- Làng Mai, 26.

- On applying Buddhism to the modern world and abolishing superstition, see for example: Trí Hải, “The Harms of Superstition,” Đuốc Tuệ 249-250 (15 April 1945): 3-7 and “Nhân Gian Phật Giáo” [Worldly Buddhism], Đuốc Tuệ 92 (1 September 1938): 3-7. On the teachings of the historical Buddha, see: Nguyễn Trọng Thuật, “Xã Hội Phật Giáo” [Buddhist Society] Đuốc Tuệ 107 (1 May 1939): 3-10.

- See for example: Tâm Trực (Lê Đình Thám), “Đạo Phật có làm cho Người ta Hèn Yếu Không?” [Does Buddhism Make People Weak?] Viên Âm 33 (October-November 1938): 10-21 and “Phật Pháp đối với Hiện Đại Trong Xứ Ta” [Buddhism and Modern Times in Our Country], Viên Âm 36 (April-May 1939): 10-13.

- Tâm Quán (Thích Nhất Hạnh), “Chú Dương” [Brother Duong] in Tình Người [Humanity] (Saigon: Lá Bối, 1964). The book Tình Người is a collection of essays reflecting on his time as a novice which were first written for Phật Giáo Việt Nam.

- Ibid.

- Tâm Quán, “Tiếng Chuông Giao-Thừa” [The New Year’s Bell] Phật Giáo Việt Nam 17-18 (15 December 1957): 26-32.

- Làng Mai, 25. According to interviews by Takashi Oka with Thích Trí Quang, monastics who suffered at the hands of French forces included Thich Tri Thuyen, who was killed while enrolled as a student at Báo Quốc, and Thích Đôn Hậu, abbot of Thiên Mụ Pagoda in Huế, who was beaten by French interrogators. Takashi Oka, “Buddhism as a Political Force – II,” July 21, 1966, Newsletters about the Vietnamese War Sent by Takashi Oka from Vietnam, Japan and Austria to the Institute of Current World Affairs (New York: Institute of Current World Affairs, 1968).

- This timing is implied, but not explicitly stated, in “Thich Nhat Hanh: Extended Biography.”

- Nhất Hạnh, “Sangha Building,” Mindfulness Bell 34 (Summer 2003): 54-55. This article was adapted from a dharma talk given at Joongang Sangha University in Kimpo, Korea on 31 March 2003.

- Ibid., 55.

- “Thich Nhat Hanh: Extended Biography.”

- When the Báo Quốc Institute was first founded in 1932, the curriculum included foreign languages and philosophy, but these subjects were later dropped. In late 1951, some monks told Nhất Hạnh that the curriculum had changed again to include biology, philosophy, and science. Takashi Oka, “Buddhism as a Political Force – I,” 17 July 1966, Newsletters about the Vietnamese War Sent by Takashi Oka; Làng Mai, 39.

- His two friends took the names Chánh Hạnh (formerly Đức Trạm), and Đường Hạnh (formerly Tâm Cát). The name Nhất Hạnh is a reference to Vạn Hạnh, the name of a Vietnamese Zen master from the tenth to eleventh centuries. Vạn Hạnh means ten thousand actions while Nhất Hạnh means one action. Làng Mai, 34; King, “Thich Nhat Hanh and the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam: Nondualism in Action,” 322.

- Temples where Nhất Hạnh lived and/or taught from 1949-1959 include: Hưng Đạo, Giác Nguyên, Lâm Hoa, Ấn Quang, Pháp Hải, Long Vĩnh, and Phước Hòa in Sài Gòn; Linh Quang, Linh Sơn, and Viên Giác in Đà Lạt; and Phước Huệ and Phương Bối in Bảo Lộc. Làng Mai, 35-41, 51, and 69; Meeting with Thích Thanh Tân (abbot of Linh Quang Temple), Đà Lạt, 11 January 2023; Meeting with Thích Viên Như (abbot of Linh Sơn Temple), Đà Lạt, 11 January 2023.

- Làng Mai, 35-40.

- Làng Mai, 40.

- Initially called Trí Tuệ Am when it was founded by Thích Trí Hữu in 1949, the temple was renamed Ấn Quang in the early 1950s and became the center of Sài Gòn Buddhist political activity in the 1960s. Làng Mai, 35-36; Nhất Hạnh, cover letter, Application for Fellowship, Scholarship, or other Educational Exchange Grant in the United States of America, 1 April 1961, Princeton Theological Seminary.

- Nhất Hạnh, cover letter, Application for Fellowship, Scholarship, or other Educational Exchange Grant in the United States of America, 1 April 1961, Princeton Theological Seminary.

- Làng Mai, 51; Trí Không, 44-45 and 142.

- Làng Mai, 53.

- The Làng Mai biography does not cite records of Nhất Hạnh’s bachelor’s degree from Saigon University. Nhất Hạnh’s studies toward a bachelor’s degree are also not mentioned in his 1961 Fulbright Scholarship application, which lists only his high school education in Đà Lạt and Buddhist studies at Ấn Quang.

- Nhất Hạnh, Tiếng Địch Chiều Thu [Reed Flute in the Autumn Twilight] (Saigon: Long Giang, 1949); Ánh Xuân Vàng [The Golden Light of Spring]; Đông Phương Luận Lý Học [Oriental Logic] (Hương Quê, 1950); Là Phật Tử [Being Buddhist] (Hương Quê, 1953); Gia Đình Tin Phật [Buddhist Family] (Hanoi: Đuốc Tuệ, 1953); Hoàng Hoa, Thơ Ngụ Ngôn [Fables] (Đuốc Tuệ, 1950); Thạc Đức, “Đạo Phật Qua Nhận Thức Mới” [A Fresh Look at Buddhism], Dân Chủ (1955). “Thich Nhat Hanh: Extended Biography.”

- Trí Không, 63. Liên Hoa magazine here was based in Đà Lạt and should not be confused with the Liên Hoa magazine established in Huế some years later (1955-1966).

- Dân Chủ was run by Vũ Ngọc Các, who often published pieces about freedom and democracy and criticized the Diệm regime. Trí Không, 56.

- Thạc Đức, Đạo Phật Qua Nhận Thức Mới [A Fresh Look at Buddhism] (Saigon: Hội Phật Học Nam Việt, 1957).

- “Bản Tuyên Ngôn Thành-Lập Tổng-Hội Phật-Giáo Việt-Nam” [Founding Charter of the General Buddhist Association] Phật Giáo Việt Nam 1 (15 August 1956): 40-41. For more on the founding of the General Buddhist Association, see: Guilhem Cousin-Thorez, “The General Buddhist Association of Vietnam 1951–1964 (Tổng Hội Phật Giáo Việt Nam): A Forgotten Step Towards the 1964 Buddhist Church,” Russian Journal of Vietnamese Studies 2021 special issue: 103–113.

- “Bản Tuyên Ngôn Thành-Lập Tổng-Hội Phật-Giáo Việt-Nam.”

- Làng Mai, 40 and 68.

- Thư Viện Huệ Quang, introduction to reprinted volumes of Phật Giáo Việt Nam (HCMC: Thư Viện Huệ Quang, 2014).

- Cousin-Thorez, 108. I am unable to confirm if the GBA provided a subscription to all its members but given the main purpose of the magazine was to keep GBA membership informed, its readership was likely comparable to membership numbers.

- This is from my own reading of PGVN, counting only the articles attributed to Nhất Hạnh’s own name and his confirmed pen names (see note 51 for more on his pseudonyms).

- These pen names were identified through interviews with Sister Chân Không in 2019; Thích Nhất Hạnh’s Vietnamese language biography Đi Gặp Mùa Xuân; and his extended biography on the Plum Village website. Besides the names listed here, I believe that Tâm Tuệ and Trọng Đức were two other pseudonyms used by Nhất Hạnh based on the names, ideas, and writing style. Tâm Tuệ wrote about Buddhist schools and temples including Báo Quốc and Ấn Quang, which Nhất Hạnh considered his intellectual homes. Trọng Đức wrote on the topic of Vietnamese Buddhist unification, which was Nhất Hạnh’s primary concern at the time. The names Tâm Tuệ and Trọng Đức follow the pattern of several of Nhất Hạnh’s confirmed pseudonyms, sharing one part of a name among two different pseudonyms, for example: Minh Hạnh and Minh Thư; Tâm Kiên, Tâm Quán, and Tâm Tuệ; Thạc Đức and Trọng Đức. In a text message exchange in 2023, Sister Định Nghiêm, who edited Nhất Hạnh’s biography, said many people believe Trọng Đức was one of Nhất Hạnh’s pen names, but Nhất Hạnh himself never confirmed it.

- Nhất Hạnh, Nẻo Về Của Ý, 17.

…

Nguyên Ân Revives the Portrait of Phan Khôi Once Again

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 22 – Subjects and Sojourners

“First Thắng, Second Chinh, Third Thanh, Fourth Trưởng”: The Four “Incorruptible” Generals of the ARVN

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 21 – Living Abroad

Toward National Buddhism: Thích Nhất Hạnh on Buddhist Nationalism and Modernity in the Journal Phật Giáo Việt Nam, 1956-1959 (Part 2)

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

National Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES4 years ago

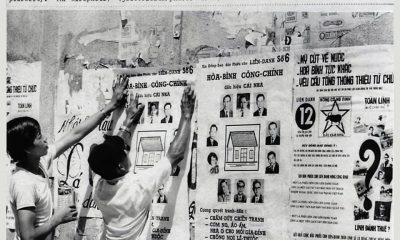

ARCHIVES4 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoChina’s Recent Invention of “Nanhai Zhudao” in the South China Sea (Part 2: Examining the “Nanhai Zhudao” legal basis)

-

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)