Editor’s Note: The following is one installment of a five-part essay series by Nguyen Luong Hai Khoi, which details the history of legal thought in Vietnam from 1945 onward. This series was originally posted on our Vietnamese language site in 2019 and has been translated here by our English editor Vinh Phu Pham.

A History of Legal Thought 1945 – 1956

Part 1: Republican Spirit 1946

Part 2: The February 1948 Letter – Law Must “Unite” with Administration

Part 3: The Attack of the Communists

Part 4: Responding to the Ideal of “Independent Judiciary,”

Part 5: Ho Chi Minh’s Legal System after the 1948 Debate

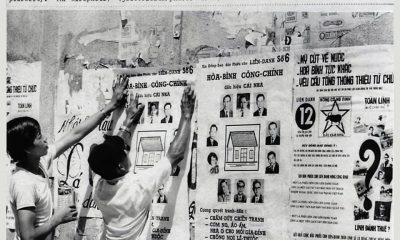

More than a month after the National Legal Conference from February 25-27, 1948, communist individuals wrote their first article attacking the independent legal viewpoint of the legal profession in the newspaper “Truth,” the propaganda organ of the Communist Party, on April 15, 1948.

The leaders of the legal profession then countered the viewpoint of the communist individuals in the newspaper “Independence,” an organ of the Democratic Party, two months later. The debate continued until the end of 1948.

The Significance of the Debate

Although this debate initially focused on whether the legal profession should be “independent” or “dependent” on the executive branch, from the outset, the communist individuals introduced another theme: whether to follow the path of “class struggle” advocated by the “people.”

As a result, this debate carried implications beyond the realm of jurisprudence. It marked a turning point in defining the purpose of the revolution, namely the contemporary anti-French colonial resistance: whether the struggle was for building a “national independence” or for embracing the path of “communism.”

Key figures of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam at that time closely monitored the debate because everyone understood that the outcome of this debate would determine Vietnam’s future path: communism or republicanism.

Representing the communist perspective was journalist Quang Đạm, who was then an editor at the newspaper “Truth.” His real name was Tạ Quang Đệ. Before 1945, he served as a district court clerk in Thiệu Hoá district (Thanh Hóa province), and later he was promoted to a higher position in Hà Trung district (also in Thanh Hóa province). After 1945, he joined the Viet Minh. In early 1947, he caught the attention of the General Secretary of the Party, Trường Chinh, and was appointed to work for the “Truth” newspaper.

Journalist Quang Đạm

Quang Đạm was a journalist who served his leadership until his last breath.

He translated many works of Mao Zedong into Vietnamese, including “On Protracted War,” which helped Trường Chinh transform the work into the essay “Certain Victory in Protracted Resistance War” in 1947.

In 1948, he was tasked with writing articles attacking the independent legal thought of intellectuals and politicians within the government, aiming to transform that legal system into communist jurisprudence. After 1954, he was assigned to write articles attacking the creative freedom of artists and writers of Nhân văn – Giai phẩm (article “The Relationship Between Politics and Literature,” Nhân dân newspaper, October 1, 1956). By the early 1960s, he was given the task of attacking the moderate politicians in Hanoi with the opening article “Shattering the Dogma of Reexamination” (This was also the first usage of the term “reexamination doctrine”).

Due to his writing as a political tool for leadership, in the opening article of the attack on the spirit of independent legal thought on April 15, 1948, even though he was just an editor at the “Truth” newspaper, Quang Đạm wrote as if he were an unofficial spokesperson for the Party leadership.

Legal system is a component of the administration

The fundamental perspective of Quang Đạm and the “Truth” newspaper is to deny the independence of the legal system. To argue this point, he categorizes the legal system within the realm of “government agencies,” grouping it alongside “science,” “education,” “medicine,” “arts,” and so on, essentially as a managed part of the administration (government). Quang Đạm raises the issue in the opening passage as follows:

“The legal system is a branch of the state. The state is like a machine, and generally speaking, the legal system is a part of that machine.”

This is not Quang Đạm’s personal viewpoint. The “Truth” newspaper, the official media outlet of the Communist Party, used the “Introduction” section to introduce Quang Đạm’s article as follows:

“All political, military, economic, and cultural sectors this year, under the guidance of President Hồ and the Government, are striving to contribute fully to the resistance. In order to play a part in the nationwide competitive movement, our ‘Truth’ newspaper dedicates a special section to publish articles on specialized fields, science, legal matters, education, medicine, and the arts.”

Therefore, the article reflects the viewpoint of the entire Communist Party, not just Quang Đạm’s personal perspective.

Legal system serving class struggle

To justify the constraint of the legal system within the realm of administration, Quang Đạm presents the argument:

“Since society became divided into classes and states, the legal system emerged to suppress opponents and protect the dominant forces. In the advanced stages of societal progress, once human society erases all traces of class, the state machinery is put ‘in a museum,’ as Engels said. Similarly, the legal system only retains value as an antique.”

In this manner, Quang Đạm, or the Communist Party, employs the Marxist-Leninist viewpoint on law. The first premise of this legal perspective is that nothing lies beyond the realm of class struggle, and the legal system is no exception. Building on this foundation, Quang Đạm proposes a second premise:

“Therefore, the significance, form, and effects of the legal system must change according to the era and social regime. (…) For the same reason, the democratic republic of Vietnam after September 2, 1945, could not establish a legal system before August 19, 1945, and the consciousness, concepts, and ideas of those with legal authority must be revised to align with the new democratic regime.”

Hence, an independent legal system is a product of the old regime and does not align with the “new democratic regime.” The article does not explicitly define what the “new democratic regime” is, but it should be noted that this term, used by the communists after 1945, refers to a “communist regime.”

In the same issue of the “Truth” newspaper (issue 91), right beside Quang Đạm’s article “Legal System and the State,” there is another article titled “Recording the Progress of the Democratic Forces,” praising the Communist Party of Yugoslavia for its February 1948 coup supported by the Soviet Union, which “eliminated reactionaries, built a new democracy.”

Specifically, the article praises how the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, after seizing power, economically seized “large factories, banks, carried out agrarian reform, eradicated reactionaries,” and “about 93% of industry in Yugoslavia was nationalized.” Politically, they eliminated the “Democratic Party of Socialists as a main instrument of American reactionaries” and “boldly advanced, keeping pace with democratic countries, following the path of the Soviet Union” (page 9).

In summary, the “new democratic regime” is essentially a “communist regime.” Thus, the message from Quang Đạm, representing the communists, in the above excerpt is clear: an independent legal system is a product of the bourgeois era and cannot exist within the framework of a communist regime.

Later on, the author analyzes the differences between the political system and the “old” and “new” legal theories by writing the history of Marxist-Leninist ideology:

- “The theory of independence and separation of powers [i.e., independent legal theory within the framework of the three separate powers] with all its abstract beauty” may have had value in the past as it helped the bourgeoisie in Europe limit the power of the feudal class to carry out the bourgeois revolution and seize political power.

- Once in a dominant position, the bourgeoisie only uses the “separation of powers” as a mythical cover to conceal its oppressive and exploitative nature. According to the author, in reality, the legal system under the bourgeois regime is only “a fake independence” and not truly independent like they claim, but merely a tool of the bourgeoisie to subjugate the masses.

- Tracing the history of the spirit of “separation of powers” in capitalist countries to the modern history of Vietnam, the author asserts that from the 1920s, when the “wave of democracy [i.e., communism] swept through Indochina,” French colonialists established “Consultative Assemblies” and showcased the label of “independent legal theory.” According to the author, the claimed independence of Vietnam’s legal system during the French colonial period was merely deceptive.

Having acknowledged that historical legal affairs – administration – legislation centered on the monarchy and aristocracy led to scenes of “cruel oppression” under the feudal regime, having accepted that the “separation of powers” model of the capitalist regime holds a certain “abstract beauty” and value in the struggle against feudalism, then criticizing capitalism for constructing a deceptive “separation of powers” model, and that independent legal theory is merely “a fake independence,” logically and linguistically, Quang Đạm concludes that the “new democracy” regime, i.e., communism, will implement the “genuine independence” of the legal system.

However, according to Quang Đạm, no, if the capitalist regime only constructs a “fake independence” legal system, the communist regime, in his view, will not establish a “genuine independence” legal system, but instead will control it.

Therefore, does the “new democracy” regime differ from the feudal regime only in terms of conceptual terminology? How can this “new democracy” regime control the legal system while still differing from the feudal regime? Quang Đạm explains using the arguments of Marxist-Leninist ideology:

“Under a reactionary state, the legal system must stand with the standpoint of the masses, be separate and have a division of powers from the state in possible circumstances. But in a new democratic regime like our country now, where the state belongs to the progressive people, the legal system must combine with the state to counteract destructive forces against the government. Only then can a practical and progressive determination regarding independence and separation of powers be made.”

Quang Đạm still uses the concept of “independence and separation of powers,” but he reinterprets them, causing these concepts to shift their meaning to a completely different context. The judiciary must be independent, even confrontational, but this independence and confrontation are directed against the enemies of the “People.”

Here, the author does not explain what “People” means, but asserts that “under the new democratic regime, the State belongs to the progressive people.” Therefore, the independence and confrontation of the judiciary against the enemies of the “People” also means that it must be independent and confrontational against the enemies of the “State.”

In other words, the judiciary is not independent from the administration; instead, it must be under the leadership of the administration to attack its enemies. The author explains further in the concluding passage:

“Independence must coordinate with unity, meaning it must stand in a common front of the people and the State of the people to counteract the schemes of the enemy, to resist the wrong consciousness and ideas of the old regime and theory that still linger in people’s minds.

Separation of powers must coordinate with concentration of powers, meaning it must divide powers through the assignment of responsibilities within the scope of specialization under the overall guidance of the group principle.”

Here, the author clearly expresses that forcing the judiciary back under the administration is a process of ideological reform to combat the “consciousness and ideas” of the “old theory” that still persist in the minds of intellectuals.

The emphasis is on the aspect of ideological reform in eliminating the notion of independent legal theory, placing the judiciary under the control, the “comprehensive leadership” of the administration, as the author affirms it to be a step toward building the “new democratic regime”:

“This is not a compromise during the resistance, but a crucial principle in the new democratic regime.”

Therefore, for the author, the requirement for legal intellectuals to accept the comprehensive leadership of the administration, i.e., the executive apparatus that the Communist Party has integrated into, is not a temporary “compromise” in the context of the resistance, but a necessary step to establish the communist regime, a principle that Communist individuals cannot compromise on.

It can be said that this article fully expresses the ideological framework of the leaders of the Communist Party of Vietnam in 1948: The elimination of independent legal theory. Author Quang Đạm emphasizes this, as if not wanting legal intellectuals to misunderstand it as a situational and obligatory solution during the war, but rather as a step towards the communist world.

Personal attacks against legal professionals

In addition to asserting the removal of independent legal theory to construct a communist political system, the author simultaneously employs a strategy of personal attacks against legal intellectuals. He speaks of the mindset of legal intellectuals as follows:

“Some intellectual elements within the legal profession, gazing at their humble status next to the authoritarian power of the parental officials, always seek comfort in the ideal of independence. (…) When the August Revolution erupted, with the establishment of the people’s government, these elements were utilized. Due to their self-esteem, the ideology of freedom of the intellectual class, social consciousness, and adherence to theory, due to envy of status and power, some intellectuals maintained a separate attitude from the people’s government. Advocating for ‘independent legal theory to protect individual freedom’ was seen as an absolute eternal truth (…) many times, the task of suppressing counter-revolutionary forces stumbled upon these erroneous attitudes and misconceptions.”

Here, the author simply borrows Marxist-Leninist arguments about the “essence of petty bourgeoisie” among the “intellectual class” to label the “targets.” The explanation of the independent legal mindset of legal intellectuals is illustrated by depicting their characteristics as “gazing at their humble status,” “self-esteem,” “envy of status and power.” This is the first time the method of denunciation is experimented with publicly at the state level.

This denunciation strategy, as we know, would be widely used from two years after that in various campaigns such as criticism, self-criticism, land reforms, Nhân Văn – Giai Phẩm, the reform of the Southern bourgeoisie (after 1975), and continues to be employed in political discourse and even academic discourse in Vietnam today whenever conditions allow.

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago