Politics & Economy

A History of Legal Thought in Vietnam, 1945–1956 – Part 4: The Ideal of ‘Independent Judiciary’ Responds

Published on

Abstract

This essay discusses the ideological debate over judicial independence in Vietnam during 1948, highlighting a critical moment in the country’s legal and political history. It focuses on the intellectual clash between republican legalists, led by Vũ Trọng Khánh and Vũ Đình Hoè, and communist proponents of state-controlled jurisprudence, represented by Quang Đạm. In response to Quang Đạm’s attack on the principle of judicial independence, Vũ Trọng Khánh defended the judiciary’s role as a protector of justice above class interests, emphasizing the need for an autonomous legal system to safeguard individual rights. Vũ Đình Hoè reinforced this stance by grounding his arguments in the 1946 Constitution, asserting that the judiciary should serve the people, not the state apparatus. The essay reveals how the communists reframed legal independence as opposition to the state, ultimately resorting to threats of force, which ended the debate. This ideological conflict reflected the broader struggle between republicanism and communism, shaping Vietnam’s future legal and political landscape.

Keywords: Vietnam, legal thought, Republicanism

Editor’s Note: The following is one installment of a five-part essay series by Nguyen Luong Hai Khoi, which details the history of legal thought in Vietnam from 1945 onward. This series was originally posted on our Vietnamese language site in 2019 and has been translated here by our English editor Vinh Phu Pham.

A History of Legal Thought 1945 – 1956

Part 1: Republican Spirit 1946

Part 2: The February 1948 Letter – Law Must “Unite” with Administration

Part 3: The Attack of the Communists

Part 4: Responding to the Ideal of “Independent Judiciary,”

Part 5: Ho Chi Minh’s Legal System after the 1948 Debate

After the attack on the spirit of independent judiciary by Quang Đạm, the leaders of the legal sector wrote rebuttals.

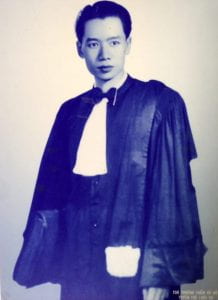

Representing the Republican politicians in the Ho Chi Minh government who spoke out against the communists was Vũ Trọng Khánh, a former lawyer during the French colonial era, the mayor of Hải Phòng during the government of Trần Trọng Kim, and the first Minister of Justice of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1948, currently serving as the Director of Legal Affairs in District 10.

Bộ trưởng Bộ tư pháp đầu tiên, Vũ Trọng Khánh. Năm 1948 là Giám đốc tư pháp khu 10.

The article by Vũ Trọng Khánh, titled “Reader Opinions on Legal Issues,” was also published in the newspaper Sự thật, issues 98 and 99, on August 19 and September 2, 1948. His writing was reprinted in full by Vũ Đình Hòe in the appendix of “Pháp quyền nhân nghĩa Hồ Chí Minh” (Legal Ethics of Ho Chi Minh). The excerpts below are taken from the book “Hồi ký Vũ Đình Hòe,” which includes three works: “Báo Thanh Nghị và nhóm Thanh Nghị,” “Tiền Thanh Nghị,” and “Pháp quyền nhân nghĩa Hồ Chí Minh” (hậu Thanh Nghị), published by Hội Nhà văn in 2004.

Vũ Trọng Khánh: The Judicial Function of Justice Protection

Firstly, Vũ Trọng Khánh rejects the theory of communist jurisprudence by denying the legitimacy of “class struggle.” According to him, the law is not just a tool of the ruling class; rather, it is a tool to protect the weak against the strong, in other words, to uphold justice. Moreover, when the law addresses conflicts between individuals in society, it has nothing to do with class struggle.

In his view, the law not only reflects the will of the ruling class but also reflects the customs and beliefs of the “people.” Vũ Trọng Khánh uses the concept of “people” to encompass all social groups, classes, and categories, transcending class distinctions.

It is evident that Vũ Trọng Khánh opposes Quang Đạm and the leaders of Quang Đạm on the following concepts: Firstly, the function of the judiciary. Quang Đạm sees the judiciary as having the sole function of “punishment” in the class struggle, specifically punishing those who oppose the “new democratic regime,” meaning the socialist communist system. Rejecting this, Vũ Trọng Khánh asserts that the function of the judiciary is not related to class struggle but rather to the protection of justice. This function of justice protection stands higher than class opposition and political systems. He poses a simple question that class struggle theorists never answer: “When Article 712 of the Civil Law stipulates that anyone causing harm to others must compensate the victim, and the Penal Code prosecutes those who fight or kill not for political reasons, who is being protected and which class is being oppressed?” (“Hồi ký Vũ Đình Hòe,” as cited in the referenced book, page 1088).

When emphasizing the function of the judiciary as protecting justice rather than punishing those who the “state” wants to eliminate, Vũ Trọng Khánh compels Quang Đạm and his leadership to confront the Constitution and the legal decrees of 1946 that President Hồ Chí Minh signed and which are still in effect. Based on this, Vũ Trọng Khánh asserts that the judiciary needs to be independent to protect individuals against the powerful, including those with authority.

Secondly, the understanding of the concepts of “opposition” and “independence.” Quang Đạm intentionally associates “independence” with “opposition” by claiming, “The state of judicial independence will turn into opposition.” Once again, Quang Đạm generalizes without explaining why “independence” will turn into “opposition.” Clearly, the message from Quang Đạm and his leaders in this generalization is evident: not obeying us (independence) means opposing us (opposition). The threat of violence is implicit in this generalization. In response, Vũ Trọng Khánh answers:

“The tasks of the judiciary and the tasks of administration are assigned to two different agencies, and it is a condition to ensure that one agency does not encroach on the other, protecting citizens from oppression by the authorities in any democratic regime.” (“Hồi ký Vũ Đình Hòe,” as cited in the referenced book, page 1090)

And:

“When someone orders the court to handle things in a certain way, and the court does not comply, we believe that is maintaining independence. If Mr. Quang Đạm thinks that is opposition, then I want to ask him, when judges intervene in administrative or political matters, how will administrative committees behave to avoid becoming ‘opposed’?” (“Hồi ký Vũ Đình Hòe,” as cited in the referenced book, page 1091)

Vũ Trọng Khánh’s response directly addresses the understanding of the concept of “independence” in “Independent Judiciary.” While Quang Đạm and Sự thật newspaper intentionally steer the concept of “independence” so that it slides from “independence in terms of power from the executive” to the meaning of “independence” from other specialized fields such as health care, arts… under the management of the executive, Vũ Trọng Khánh restores the concept of “independence” to its original meaning.

Thirdly, the understanding of the concept of “people.” Quang Đạm uses the term “people” interchangeably with the “state,” meaning the executive. In terms of logical reasoning, for Quang Đạm’s argument to hold, he must explain why the executive, which is the individuals controlling that agency, is indeed the “people.” Of course, Quang Đạm does not explain this because it is unfeasible. Quang Đạm’s notion of “people” clearly has an “excluding” nature based on hierarchical divisions: if the “people” are the “state,” and the “state” is the “people,” then the remaining part of the “people” consists of only two categories, the “progressive people” following the “state” and the remaining “objects.” Rejecting this, Vũ Trọng Khánh regards the “people” as a large, inclusive entity, with a “comprehensive” nature rather than an “excluding” one. “People” include all classes, social strata, and components of society.

Fourthly, Quang Đạm utilizes the concept of “unity” that President Hồ Chí Minh had used in the letter sent to the national judiciary conference in February 1948, to tether the judiciary to the executive. In contrast, Vũ Trọng Khánh asserts that “independent judiciary” will only help the government in times of strong resistance because protecting justice for the people means safeguarding their trust in the government:

“Mr. Quang Đạm advises: ‘The judiciary must unite with the state in opposition to the destructive forces against the government. No part should separate itself from the collective unity.’ In response to these strange words, I only ask: ‘Are the judges who have been part of the resistance so far considered inside or outside the collective unity? When the judiciary punishes those who wrongfully arrest others but pardons those arrested without evidence, is that undermining or strengthening the government?'” (“Hồi ký Vũ Đình Hòe,” as cited in the referenced book, page 1092)

We can see that those who adhere to communism remain perpetually silent in the face of this question posed by the founding figure of the legal system in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. This is because, once the path of communism is chosen, these are questions that cannot be answered.

The text discusses the communist ideology and its relationship with the legal system. There is an interesting detail in Vũ Trọng Khánh’s response to Quang Đạm, particularly regarding the feasibility of communism.

Quang Đạm believes that in the progressive evolution of human society according to communism, society will no longer have classes, and the state apparatus will perish by itself. In that scenario, the legal system will also cease to exist. Therefore, there is no need to maintain an independent legal system. Vũ Trọng Khánh addresses this argument by Quang Đạm with two counterarguments.

Firstly, in a communist society where there are no classes, no state, and no laws or courts, it is merely a distant future dream. Currently, people still need the state, including administration, judiciary, military, etc. He immediately cites the example of Russia, the elder brother of the communist bloc, where both laws and courts still exist.

Secondly, “according to dialectical materialism, it is not certain that a communist society will be free from contradictions that will necessitate further transformations. A more scientific attitude is to think that we cannot determine what motives a communist society will contain, so we cannot hastily say that at that time, Administration, Military, and Judiciary will disappear entirely. Perhaps, they will only change in form and organization. Despite debating this point, it is like searching for where the Earth originates and where it will go” (“Hồi ký Vũ Đình Hòe,” as cited in the referenced book, page 1088).

As mentioned earlier, Vũ Trọng Khánh was a member of the Marxist research group during the People’s Front in 1936 of the Communist Party. He understands communism theoretically and has directly pointed out internal contradictions in its theory. The fundamental tenet of communism – the abolition of classes and the state, including the legal system – was critically examined by Vũ Trọng Khánh, addressing both practical (in Russia) and theoretical aspects. The subsequent responses from the communists never addressed the issues Vũ Trọng Khánh raised.

The debate between Vũ Trọng Khánh and Quang Đạm focuses on the issue of the legal system but inevitably confronts the foundational issue standing behind that legal issue: the question of the path for Vietnam – communism or republic.

Vũ Đình Hoè: Look at the 1946 Constitution

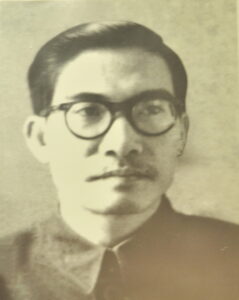

Following Vũ Trọng Khánh, Minister of Justice Vũ Đình Hoè wrote an article titled “Judiciary in the New Democratic Regime” (published in the “Độc lập” newspaper, July 1948), continuing to affirm that the legal system under his leadership stood for the people, safeguarding justice for the people. At the same time, Vũ Đình Hoè positioned Quang Đạm against himself in terms of logical reasoning.

Vũ Đình Hoè, Bộ trưởng Bộ Quốc gia Giáo dục đầu tiên (1945-1946), Bộ trưởng Bộ tư pháp từ 1946 đến 1960.

Vũ Đình Hòe also argued that from the feudal era to the colonial period, Vietnam had never experienced an independent judiciary. He asserted that the independence of the judiciary is a “revolutionary” element that the people only obtained through the August Revolution.

Therefore, Vũ Đình Hòe’s message is clear: the essence of the revolution must be to eliminate the “pretend independence” of the “bourgeois” and “colonial” legal systems to establish a “genuine independence” legal system, rather than eliminating the inherent “independence” of the legal system.

Continuing, Vũ Đình Hòe compelled Quang Đạm to confront the concepts of “people” and “class” once again. He argued that it is not the “class” but rather the “people” themselves who are the only legitimate foundation to elect representative institutions, such as the National Assembly and local People’s Councils. These representative bodies, chosen by the people, appoint the judges of the judiciary.

Thus, once again, Vũ Đình Hòe compelled Quang Đạm and his leadership to face the 1946 Constitution: the supreme state power is held by institutions elected by the people, not the “new democratic” state (i.e., the Communist Party).

In other words, Vũ Đình Hòe rejected Quang Đạm’s viewpoint that equated the “state” with the “people” and, at the same time, argued that the executive branch must be accountable and subject to checks and balances in terms of power.

In his response, Quang Đạm wrote an article titled “Some Basic Points on the Legal Issue,” published in the newspaper “Sự thật” on November 15, 30, and December 19, 1948.

Unable to address the points he couldn’t refute, Quang Đạm employed the “cultural debate” of the new era, repeating old viewpoints as if they had never been rebutted and continuing to attack his opponents more fiercely.

In this article, Quang Đạm still couldn’t explain why the “state” could be equated with the “people.” According to him, the reason is that the government consists of the most outstanding individuals among the people. However, he didn’t explain what “outstanding” meant, what standards determined who was outstanding or not, and most importantly, why these “outstanding” individuals of the government, assuming they exist, would make the “state” equivalent to the “people.”

Based on reiterating a viewpoint that had been rejected, Quang Đạm continued to criticize the activities of the judicial sector, such as ordering the release of individuals unlawfully detained by local authorities mentioned in Minister of Justice Vũ Đình Hoè’s “Report on a Year of Resistance Activities of the Ministry of Justice” on February 15, 1948.

Quang Đạm argued that respecting the “people” means obeying the government’s orders. Local judicial authorities are closer to the “people” than the central government, so they understand the desires of the people better. Therefore, their decisions also reflect the wishes of the people. Consequently, the judicial sector “serving the people” must respect the decisions of local governments.

When local judicial authorities arrest “Viet traitors,” they are only carrying out the “wishes of the people.” Legal procedures related to the arrest of individuals cannot be as important as the “wishes of the people.”

Starting with class struggle, then equating class with the people, and finally using the concept of “people” in such a vague way that it has no substance, Quang Đạm knew that his arguments could not refute the ideals of the republicans. He concluded with a threat:

Before the Supreme Court is the Court of the people, under the supreme law is the will of the people, whoever intentionally or unintentionally clings to the legal form against the spirit of the law, will inevitably face a simple but worthy indictment and punishment of the people.

In the debate, whoever resorts to the use of force is deemed intellectually incapable. Subsequently, there were no more responses from the republicans to the communists. Once the debate had escalated to the stage of threatening the use of force, for the intellectuals aligned with the Republic in the government of Ho Chi Minh, there was nothing left to argue, only the matter of choosing their own political path.

Afterwards, in the “Truth” newspaper, the communists continued to write articles. A year after the initial attack, in April 1949, the author “Tan Dan” wrote an article titled “Vietnamese Jurisprudence – Independence or Dependence” in the “Reader’s Opinions” section of the “Truth” newspaper (Issue 110, 25/4/1949).

“Tan Dan” recalled the debate, simply reiterating Quang Dam’s points as if these had never been refuted. Tan Dan admitted that the 1946 Constitution stipulated “independent judiciary.” The author sarcastically undermined the spirit of independent jurisprudence, attributing it to the ideals of the French republic, but “dismissed” it by reiterating Quang Dam’s explanation of the meaning of the term “independence.” Tan Dan went further than Quang Dam in one aspect by specifically mentioning the Soviet Union: advocating for the elimination of independent jurisprudence, placing the judiciary under the control of the executive, as it was the “progressive” path of the Soviet Union.

References

Sherry Jr, Vincent J. The evolution of the Legal System of the Republic of Vietnam . The University of Southern Mississippi, 1973

Tuan, H. P., Nguyen, C., Nguyen, D. L., Khôi, N. L. H., Nguyen, M. T., Minh, N. T., … & Zinoman, P. B. (2022). Building a republican nation in Vietnam, 1920–1963. University of Hawaii Press.

Nguyen, M. T. (2022). The Self-Reliant Literary Group and Colonial Republicanism in the 1930s. Building a Republican Nation in Vietnam, 1920–1963, 61.

Thuy Nguyen; Exploiting Ideology and Making Higher Education Serve Vietnam’s Authoritarian Regime. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 1 December 2022; 55 (4): 83–104. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/cpcs.2022.1819231

Zinoman, P. (2013). Vietnamese colonial republican: The political vision of Vu Trong Phung. Univ of California Press.

Vu, Tuong and Nguyen, Thuy. “Chapter 1 “Doi Moi” but Not “Doi Mau”: Vietnam’s Red Crony Capitalism in Historical Perspective”. The Dragon’s Underbelly: Dynamics and Dilemmas in Vietnam’s Economy and Politics, edited by Nhu Truong and Vu Tuong, Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2022, pp. 25-50. https://doi.org/10.1355/9789815011401-003

Kim, T. T. (2022). Early Republicans’ Concept of the Nation. Building a Republican Nation in Vietnam, 1920–1963, 43.

Translation: The Decision in 2013 of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Certain Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform

Thủ Đức Demonstration High School: A Modern Educational Policy and Teaching Method of the Republic of Vietnam

A Proposed Outline for a Study on Republicanism in Modern Vietnamese History

Tran Le Xuan – Diplomatic Letters

Books for Boys During the French Colonial Period in Vietnam: A Case Study of Huu Ngoc’s Reading Experiences

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Politics & Economy1 year agoRethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education