Politics & Economy

Lessons from the Việt Nam war (Part 2)

Published on

By

Tạ Văn Tài

Lessons from the Việt Nam war (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3)

2. The second lesson: War should end with a negotiated peace, a political solution that sees an end to the intransigence that is appropriate for war but not for peace. South Vietnam was a small country under the tutelage of a big power, the United States, which became a paper tiger at the end for being unwilling to continue supplying weapons to South Vietnam. At the same time, South Vietnamese President Thiệu responded unrealistically to the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973 with his “Four No’s” (Bốn Không), including no coalition government with the Communists, despite his weak military position.[i] When Stalin asked, “How many divisions does the Pope have,” he was pointing out that moral legitimacy without military force is ineffective in time of war. For Vietnam, the right path was a comprehensive political strategy based on accommodation.

If President Diệm had agreed with North Vietnam to national elections in 1956 in both parts of Vietnam in accordance with the unsigned Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference on Indo-China of July 1954, there might have been a national assembly in which South Vietnam had at least nearly half the delegates. This could have resulted in a unified Vietnam in which the two sides coexisted under the observation of the international community.

Moreover, the Vietnam War (1960-1975) could have ended with a negotiated peace agreement with national elections to follow, as provided by the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, but President Thiệu worried too much about such elections and resisted preparing and organizing for them. ) [ii] At the beginning of 1975, Nguyễn Văn Hiếu, a delegate of the National Liberation Front (the Việt Cộng) at the Paris Peace Talks, asked South Vietnamese General Trần Văn Đôn to relay to President Thiệu a request to include the Front in President Thiệu’s cabinet and to form a coalition government to resist Hanoi’s controlling influence. Thiệu told Đôn to check with the Americans, and Đôn said later that the Americans had rejected that solution. In other words, Thiệu did not dare adopt a political solution crafted by North Vietnam.

There was another time, in 1971, when Thiệu reacted similarly. U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs G. Warren Nutter, a former professor of economics at the University of Virignia and a teacher of Dr. Nguyễn Tiến Hưng, asked Dr. Hưng , then an advisor to Thiệu , to suggest to Thiệu that South Vietnam should have an independent initiative for a peaceful solution to the war. Dr. Hưng proposed that Thiệu seek trade relations with the North and a rail line between the North and the South to create one market and to develop the Mekong Delta.

Thiệu mentioned these points in an October 1, 1971, election speech. But he still worried about the American reaction, and ordered that it be checked with the U.S. State Department. The American answer was “too late,” and Secretary of State Kissinger cabled U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam Graham Martin that all negotiations had to be between the United States and North Vietnam, and must take place in Paris. Thus, Thiệu did not dare invoke national sovereignty or try to persuade the United States to follow his small country’s initiative, and thereby was pulled along in a war that was really conducted by the big power. (President Diệm had been a little better. Although he agreed with the United States not to hold elections throughout Vietnam in 1956, he resisted foreign combat troops in Vietnam and at one point sent his counselor, Ngô Đình Nhu, to central Vietnam to talk peace in secret with a North Vietnamese emissary, Phạm Hùng.)

Obsessed with his rigid and unrealistic policy of the Four No’s, and consequently eschewing negotiation and accommodation, and relying on only his hope for American B-52 bombers and logistical support if attacked, Thiệu resigned when the Americans drew down their military support and pressured him to resign. Thiệu went on national television on April 21, 1975, announced his resignation, and excoriated the Americans for the “inhumane act” of refusing “to aid an ally” and for “abandoning” South Vietnam.[iii] At this point, South Vietnam’s armed forces lost their morale. In April of 1975, every day I called my cousin, Colonel Nguyen Mong Hung, chief of the Fifth Bureau of the South Vietnamese High Command, in hopes that he would tell me the real situation. In a weak, dispirited voice, he murmured: “Tài! The soldiers no longer fight!” (Previously, they had fought valiantly to repel the North Vietnamese attacks at Tết 1968 and in the 1972 battle of Quang Tri.) I asked officials in the political section of the U.S. Embassy, and they told me that satellite photos showed that military trucks and tanks were moving southward, bumper to bumper. The North Vietnamese probably knew that there would be no retaliation by the Americans, despite Nixon’s promises to Thiệu. Thus, the U.S. had decided to leave South Vietnam, to grant far-reaching concessions in the Paris Peace Accords that permitted North Vietnamese troops to remain inside South Vietnam in exchange for the return of American prisoners of war as demanded by the American public, and then discontinued the promised supply of arms to South Vietnam. Finally, the Americans even objected to the use of American economic aid funds to pay the salaries of the South Vietnamese armed forces and police.

President Gerald Ford during an address at Tulane University on April 23, 1975, declared: “Today America can again regain the sense of pride that existed before Vietnam. But it cannot be achieved by refighting a war that is finished ‒ as far as America is concerned.”[iv] By 1975, however, the last year of this civil war, the Communist troops were receiving maximum help from the Chinese and Soviets in terms of the arms, trucks and tanks used in their rush to Sài Gòn. Today, America can regain the sense of pride that existed before Vietnam.

The authority to settle between 1973 and 1975 the Vietnam War should have belonged to the partner that shed blood, South Vietnam, and should not have been vetoed by the big power that was fading out of the picture. President Thiệu could have adopted a more independent war-and-peace strategy that took into account South Vietnam’s sovereignty and interests, and dared direct negotiation between North and South Vietnam, probably through the good offices of France, and put the Americans before a fait accompli. Despite the American disengagement during 1973-1975, President Thieu was still afraid of a coup d’etat and murder similar to those terminating the Diem regime.

Adhering too faithfully, out of fear, to the demands of the big power would never have guaranteed that power’s friendship or respect, and therefore did not support the small power’s interests. If Thiệu had started working on a separate peace with North Vietnam early in the period of American disengagement (1973-75), a political compromise might have been found that would have avoided the decision of North Vietnam in 1975 to launch an all-out military push on Sài Gòn.

The need for policy autonomy by a small power also applies to North Vietnam . During both the Indochina War (1945-54) and the Vietnam War of 1960-1975, North Vietnam depended on military and economic aid from the Soviet Union and China, whose interests were not necessarily the same as those of North Vietnam, which later discovered that following its own interests might have been more advantageous. Specifically, North Vietnam found it might have been better off escalating the fighting, contrary to the wish of the big powers.

The 1954 Geneva Accords imposed the big powers’ decision to divide Vietnam into two parts at approximately the 17th parallel, with reunification awaiting elections in 1956. This plan was only reluctantly accepted by North Vietnam, whose representative, Tạ Quang Bửu, demanded that the line of partition be at the 13th parallel as the just prize for victory over the French at Diên Biên Phu. Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai, however, worried the Americans would jump in to help South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia in response to such a demand.

After consulting French Prime Minister Pierre Mendès France, Zhou Enlai proposed that North Vietnam refrain from more offensives and withdraw from Cambodia and Laos. Zhou Enlai also promised Cambodia and Laos that they would be put under the influence of China, not of North Vietnam. And he accepted partition at the 17th parallel, not the 16th , as Hồ Chí Minh had suggested in a previous meeting in Liuzhou. The Soviet Union also wanted partition at the 17th parallel.

In 1956, South Vietnamese President Ngô Đình Diệm refused to hold talks for national elections for reunification on the grounds that South Vietnam had not signed Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference on Indo-China. The United States supported Diệm’s position.

North Vietnam felt that its goal of reunification had been frustrated by the big powers’ arrangement at Geneva, even after its victory on the battlefields in 1954. North Vietnam, therefore, planned to pursue unification later. When Zhou Enlai asked Võ Nguyên Giáp in 1954, ”If the Americans do not intervene, how long it will it take to defeat the French and unify the country,” Giap answered, “only two more years.” After about six years of only a relatively low-level insurgency, North Vietnam in 1960 created the National Liberation Front, which launched the Vietnam War of 1960-1975 .

During the Vietnam War, China seemed unenthusiastic about Vietnam’s reunification. For example, Mao said: “Our Vietnamese comrades’ broom does not have a handle long enough to sweep up all Vietnam.” And Zhou Enlai once told Ngô Đình Luyện, the South Vietnamese Ambassador to the United Kingdom, that China wished to see him in Beijing as Ambassador. Although China provided food and weapons aid to North Vietnam for the war, it never wanted a strengthened, unified Vietnam capable of challenging China. North Vietnam, therefore, relied more heavily on Soviet arms aid for military campaigns like the 1968 Tet Offensive and the 1975 invasion. In any event, Soviet and Chinese military aid allowed Lê Duẩn to pursue a military solution. As long as a big power does not dare use its overwhelming force to reduce to the stone age a stubborn small country that is willing to fight “a thousand-year war,” the small country has a chance at final victory.

But if the big power dares to use maximum force, the small power that pushes its ambition too far without searching for a negotiated peace will be defeated. For Vietnam in the period 1975-90, its ambition to be the dominant power in Southeast Asia was defeated by the long resistance of the Pol Pot forces with determined Chinese support. After sacrificing men and materiel in to support North Vietnam in its war against the United States, China responded to Vietnam’s intervention in Cambodia by an invasion of northern Vietnam in February 1979. The Chinese troops withdrew in March 1979, but border skirmishes continued throughout the 1980’s. Armed conflict only ended in 1989 after the Vietnamese withdraw their troops from Cambodia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Vietnam and China normalized both party-to-party and state-to-state relations. Vietnamese Foreign Minister Nguyễn Cơ Thạch declared that from then on, Vietnam would not send young men abroad for war.

- The third lesson: War should be referred to the people as the ultimate arbiter. War should not be between armed forces directed solely by generals and their leaders, but should be supported by the population as a whole, who should be consulted when war is declared and when peace is negotiated.

Modern war often drags in the whole population. Especially in a democratic society, families across the nation must approve a war or the government will not get popular political support for it. The United States Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war. On August 7, 1964, at the request of President Johnson, Congress passed the Tơnkin Gulf Resolution, which Johnson signed into law three days later, and which stated that “Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repeal any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent any further aggression.” President Johnson, and later President Nixon, relied on the resolution as the legal basis for their military policies and activities in Vietnam.[v]

The resolution was supposedly passed in reaction to two attacks by North Vietnamese torpedo boats on the U.S. destroyers Maddox and C. Turner Joy in the Gulf of Tonkin on August 2 and August 4, 1964. In 1995, Võ Nguyên Giáp, who had been the North Vietnamese Defense Minister at the time of the supposed attacks, acknowledged the August 2 attack on the Maddox but denied that the North Vietnamese had launched another attack on August 4.[vi] It was later revealed that the U.S. administration had drafted the resolution six months before the supposed attacks on the U.S. destroyers.[vii] The resolution was repealed on January 13, 1971. Toward the end of the war, when popular support for it had declined, Congress on November 7, 1973, passed the War Powers Act over President Nixon’s veto to restrict presidential war powers.

There were two basic mistakes in the Vietnam War strategy of the United States: The first mistake was the decision to escalate the war gradually to produce a graduated deterrent effect. There was no strategy to win a rapid victory in a few months with overwhelming firepower and to avoid tiring out both the Vietnamese and American people in a protracted conflict, which is the usual strategy of the Communists. The error of not trying to achieve a decisive victory within a short time to take account of the lack of patience of the American public was shown in the protracted Paris peace talks. The long wait for a negotiated peace yielded only a leopard-skin cease-fire in place followed eventually by the hasty withdrawal of the Americans in the wake of the Communist offensive ending on April 30, 1975.

The second mistake was the lack of popular participation in the constitutional process, including a declaration of war by Congress There should have been a better strategy for mobilizing American public opinion. But President Thiệu revealed President Nixon’s letters of support only in the last days of the War when he gave some of them to Professor Nguyễn Tiến Hưng, when he sent him to United States for a last ditch appeal for help. Before that, Vietnamese Senate President Trần Văn Lắm, Vietnamese House of Representatives President Nguyễn Bá Cẩn and Vietnamese Foreign Minister Vương Văn Bắc advised that the South Vietnamese should not protest the decrease in American aid too loudly or base their position on Nixon’s letters lest South Vietnam be accused of interfering in U.S. domestic affairs. But it was they who did not understand the U.S. political system. A president’s letters of commitment were valid state papers that should have been published and shown to the U.S. Congress as a way to rally congressional and public support.

As for South Vietnamese popular support, President Thiệu should have presented the secret Nixon letters to the National Assembly to enable the representatives of the people of Vietnam to appeal to the U.S. Congress in a kind of people-to-people diplomacy. Without the above actions, South Vietnam was subject to United States diplomacy, which in the final analysis disregarded South Vietnamese public opinion.

Without the above actions, South Vietnam became the victim of the kind of one-man-show diplomacy of Kissinger, who followed the diplomatic style of early 19th century European leaders Metternich and Talleyrand, the powerful foreign ministers who at the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815 rearranged, without consulting the people’s representatives, the European chessboard nine days before Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815.

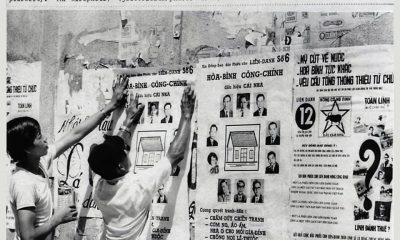

On the other hand, the Vietnamese Communists appreciated the importance of popular support. They used the terms “people’s war, people’s army,” words repeated in a book by General Võ Nguyên Giáp. The Vietnamese Communists were worried by a budding democratic regime in the Republic of Vietnam, by the election of a Constitutional Assembly that enacted a constitution in 1967, by the elections for the Senate and House of Representatives in 1967, and by the elections for half of the Senate in 1970, all with the enthusiastic participation of all strata of the people, including the various religions and political parties.

Especially noteworthy was the opposition religious bloc that had boycotted the regime previously for suppressing its struggle for a constituent assembly, the Ấn Quang Buddhists. This bloc had the greatest mass following among the population. South Vietnam’s democratizing activities had the support and encouragement of the American Ambassador, Ellsworth Bunker, a diplomat with a dignified appearance and an intense focus on democracy-building in South Vietnam and a desire to reduce the government’s military character to help it gain more legitimacy and popular support. He had help from U.S. Embassy political officers, who contacted domestic groups, including Catholic and Buddhist forces.

One prominent civilian leader with the ability to increase popular support for the regime was the charismatic law professor Nguyễn Văn Bông, Rector of the National Institute of Administration, which trained middle- to high-level civil servants. Bông wrote about democracy and about a loyal opposition. Bong had a large following within the national administrative apparatus. He and colleagues such as professor Nguyễn Ngọc Huy organized the National Progressive Movement (Phong trào Quốc gia Cấp tiến).

Ambassador Bunker said Professor Bông was a household name in Vietnam. When Kissinger came to visit President Thiệu to encourage the naming of Professor Bông as Prime Minister, the Communists assassinated him, using men directed by the R Office (the Communists’ core leadership group in the South) to firebomb his car as he was driven home from his office.

Among the Vietnamese Communists, there were some wise ones who did consult the people on the issue of war and peace. After Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1978 -‒ resulting in China launching a bloody border war to “teach Vietnam a lesson,” in the words of Deng Xiaoping ‒ Vietnamese Foreign Minister Nguyễn Cơ Thạch said that Vietnam would never again send young Vietnamese abroad to fight. Thach’s position on disengaging Vietnam from Cambodia while protecting Vietnam’s interest in a different way than the Chinese way did not endear him to China and caused China to encourage the Vietnamese Politburo to force his retirement.

Notes

[i] The Four No’s were: no negotiations with the Communists; no Communist or neutralist political activities south of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ); no coalition government with the Communists and no surrender of territory to the Communists. [Source: Phillip B. Davidson, Vietnam at War: The History: 1946-1975, (Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 740.

[ii] As pointed out by a June 17, 2012, Information Paper of the U.S. Office of the Secretary of

Defense, when the Vietnam War began for the United States is “to open a can of

worms.” As the Information Paper points out, three of the dates used as the beginning are:

- 1950, when the United States established the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), Indochina, in Sài Gòn.

- 1955: when the United States redesignated MAAG, Indochina as MAAG, Vietnam and also created a MAAG, Cambodia.

- 1961, when President John Kennedy decided to substantially increase the level of U.S. military assistance to South Vietnam.

Source: “Info paper Vietnam War and US Start Date,” www.vietnamwar50th.com, accessed 14 August 2018.

[iii] “President Nguyen Van Thieu resigns (1975),” Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com, accessed August 22, 2018.

[iv] “President Ford’s Speech on the Fall of Vietnam, 24 April 1975,” www.vietnamwar.net, accessed August 22, 2018.

[v] Our Documents, Tonkin Gulf Resolution (1964), https://ourdocuments.gov, accessed August 15, 2018.

[vi] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Gulf of Tonkin Resolution,” Britannica.com, last updated July 29, 2018, https://.britannica.com, accessed August 15, 2018.

[vii] “Tonkin Gulf Resolution.” West’s Encyclopedia of American Law, cited in Encyclopedia.com,

http://encyclopedia.com, accessed August 15, 2018.

You may like

Frustrated Nations: The Evolution of Modern Korea and Vietnam

Lại Nguyên Ân Revives the Portrait of Phan Khôi Once Again

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 22 – Subjects and Sojourners

“First Thắng, Second Chinh, Third Thanh, Fourth Trưởng”: The Four “Incorruptible” Generals of the ARVN

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 21 – Living Abroad

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

National Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoChina’s Recent Invention of “Nanhai Zhudao” in the South China Sea (Part 2: Examining the “Nanhai Zhudao” legal basis)

-

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)