After 1975

Images of Asian American women from the 20th to 21st century: Where do we go from here?

Published on

Editor’s Note: This work is an updated version of a previous publication with a Vietnamese Studies Anthology, Dong Viet(VietStream). The article has been lightly redacted for style and readability, any opinions expressed therein are solely that of the contributing author and do not reflect the stance of The US-Vietnam Review.

PROLOGUE:

I started the following article in or about 1989, after auditioning for the musical “Miss Saigon” for its debut in New York City.[ii] At that time, I had just left my job at the Washington, D.C. law firm, Wilmer Cutler & Pickering, to become a staff attorney at the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. My parents flew from Texas to Washington D.C. to visit me and to render emotional support for my first trial in court. I appeared as co-counsel for the SEC, against the defense team consisting of Arnold & Porter’s senior partner and several associates. My lead counsel was Susan Wyderko, a young Assistant General Counsel, whom I much admired. The trial, inter alia, resulted in my promotion to Special Trial Attorney in the SEC Office of General Counsel, within my first year of employment with the federal government.

In my third year of employment, I asked for an unpaid leave of absence from the SEC to pursue musical theater studies at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, after consulting Paul Gonson, Solicitor General of the SEC, a terrific tap dancer whose talent was probably not known outside the circle of his SEC staff. (We were riding the subway to Virginia together after work, and he advised me to go for the art when I was still young). After completing my training whereupon I literally learned the whole score of Miss Saigon like an understudy for the lead role, I did not return to the SEC to continue my career with the federal government, a decision I much regret.

My father must have given the 1991 version of my article to Professor Le Van, formerly Dean of Pedagogy for the University of Hue, Vietnam, before 1975. He was my father’s teacher as well as colleague. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Professor Le Van organized seminars for speakers on Vietnamese studies in connection with California’s Department of Education in Sacramento. He invited me to speak at one of those seminars and hosted me at his residence. Unbeknownst to me, Professor Le Van and his staff had placed my article in his Vietnamese Studies anthology called Dong Viet (VietStream).

The last time I saw Professor Le Van was when he and his wife visited my parents in Houston in or about 1999-2000. At the time, I was making the transition from private practice to law teaching and some of my female lawyer friends and colleagues were filing EEOC complaints and/or lawsuits against major law firms and multinational corporations for sexual harassment. I was told by a former mentor, a veteran woman lawyer and general counsel of a Fortune 500 communications company, that these women who sued or brought claims asserting discrimination or harassment would surely face a future of stigma and blacklisting, which could mean the end of a career. It was better, therefore, to “lick one’s wound” and move on to rebuild the career elsewhere.

I never forgot this confidential discussion, which confirmed the harsh reality in egalitarian America, allegedly a society of access to justice and free speech. The advice to remain “silent” jived very well with the traditional image of Asian women being part of a “culture of silence,” women of color known in America as members of a “silent minority” — being “silent” is construed to mean good citizenship.

Now comes the 21st Century. Is Asia still a “silent” culture in a not-too-silent world?

Parallel to America’s “ME TOO” movement, the 2016 U.S. presidential election opened a new chapter. First Lady Melania Trump broke barriers, overcame her immodest modeling pictures of the past, and publicly dismissed allegations regarding her husband’s sexual misconduct as “boys’ talks.” Allegations of extramarital affairs and sexual misconduct aimed at her presidential husband “are of no concerns of mine,” she told the press.

Mrs. Trump was not the first to elevate fashion models and women in entertainment to the level of “head of state” by way of marriage. The First Lady of France had shown the world that perhaps hour-glass figured Marilyn Monroe could have turned her performing artist self to distinguished First Lady in the 1960s, thereby escaping the stereotype of sex symbol, femme fatale, and tragic heroine. Almost half a century after Monroe’s death (after dozens and dozens of actresses stood up to voice their dreadful experience in a world of powerful men who “groped,” “pushed,” and assaulted), if Monroe were still alive today, in her trademarked husky voice, she would have whispered, “ME, TOO!”

The “ME-TOO” movement in America has gone too far, according to the iconic Catherine Deneuve, a Monroe admirer. The French iconic actress joined more than 100 Frenchwomen in entertainment, publishing, and academia, arguing in a letter to Le Monde that women (and men) have used social media as an aggressive forum to describe sexual misconduct, thereby publicly prosecuting private experiences and hence creating a totalitarian climate. “Rape is a crime. But insistent or clumsy flirting is not a crime, nor is gallantry a chauvinist aggression,” the letter stated. Deneuve later apologized for her signing the letter, which characterized the “Me-Too” movement as a “puritanical” “witch hunt.” In an op-ed, Deneuve explained her apology: “I have been an actress since I was 17 years old…I have witnessed situations more than delicate…Simply, it’s not for me to speak in the place of my sisters.”

Of course, among Deneuve’s sisters are quiet Asian women, found in Europe, America, Asia, Africa, in their “sub-cultures of silence,” where to say “ME, TOO” can be a badge of shame at home base, in addition to any “code of silence” imposed upon them by an outside world.

More recently (November 2019), also in the Trump Administration, an attractive Asian woman, Mina Chang, who was named deputy undersecretary in the U.S. Department of State, faced allegations of fraud, thereby tainting the image of the “good Asian girl” who climbs upward mobility. In other words, Chang has been so outspoken against the Asian female cultural norm that she actually created an alternative reality in the public domain: allegedly, she faked her Harvard credentials, and inflated her claims of experience in international human rights, charitable organizations, and leadership, in order to earn her political appointment from the Trump White House. In the history of collective Asian American female experience, has Chang rightly paid her dues?

Just before this election year, 2020, a Democrat presidential candidate and former prosecutor, the incumbent U.S. Senator Kamala Harris, a woman of color, withdrew from the presidential race. This happened after the public gained knowledge that in her younger days, she had dated an older, powerful man, allegedly to help her career. Ms. Harris maintained that her dropping out of the presidential race was because of her lack of money to continue in the expensive competition for the White House. And then the next biggest event for American women of color began: the Presidential candidate nominated by the Democratic Party, U.S. Senator Joe Biden, nominated Ms. Harris for the Vice Presidency. The team won the election, making Ms. Harris the first woman, and woman of color, to become Vice President of the United States. Ms. Harris made history, in the turmoil of the controversial Trump presidency and the 2020 Election.

Against all this backdrop, in a moment of nostalgia, I googled the internet and found my 1991 article placed in the VietStream collection anthologized by the late Professor Le Van. The VietStream anthology was the only place where my writing appeared next to works by friends and colleagues of my father, all from Vietnam–the whole generation of South Vietnam’s “best and brightest” representing the defunct country’s higher education academy to which my parents belonged. My parents and many of their university friends have passed on. This is the personal reason why I want to update this article for present publication, in memory of my parents and the late Professor Le Van, but there is also the larger reason having to do with what has been going on now, in America: mainly, the re-awakening of race and gender issues following the “ME-TOO” movement, especially in a presidential election year. I first want to have my article translated and circulated for Vietnamese readers, because I believe there is a need to look back in order to move forward. In the development of Asian American women’s public image, has there been progress or merely…regress, or a combination of both paradoxical ends, in esoteric ways?

The 2010s witnessed so much growth among Asian and Vietnamese-American women: new faces have emerged, occupying high places in public service, elected offices, art, entertainment, and entrepreneurship, all happening long after I held the music sheet for “The Rain on the Leaves” in one hand, while knocking on doors to the Johnson Liff casting agency on Broadway with the other hand, and then just a few years later, I put on a black robe to serve as the first Vietnam-born judge in America, presiding over the crowded “night court” of the inner city. I represented real diversity in both scenarios: Broadway and Houston’s municipal court!

Yet, one fact remains: as of 2020, there has not been a Vietnamese American female ambassador, U.S. Senator, Fortune 500 CEO, University president, Nobel winner, U.S. Supreme Court Justice, and many other capacities we can boldly and freely envision. Last but not least, there has been no real Vietnamese female head of state that can stand up to the 2000-year-old image of the Trung Sisters (Vietnam’s first nation-builders who led an uprising against the Han Dynasty in 40 A.D.).

But what does it mean, if and when a Vietnamese or Vietnamese-American female face finally appears in any of these capacities that can really make a difference? And what difference would that be? Do we look at the face, the genetic and ethnic roots, or do we look at the sacrifice underneath, individually, and/or collectively from many, known or unknown, who have layered bricks, paved ways, broken ground, and planted fruits?

It is for this reason that I want to revitalize this article by updating it: a look at the past, in order to stimulate deeper reflections, beyond the kindhearted Professor Le Van’s “VietStream” collection of exiled Vietnamese writings. I want to raise the challenge, and invite the answer from each Vietnamese-American, man or woman, whether such answer or vision lies with personal choices, or collective preparation, for our future’s ground of support.

~~~###~~~~

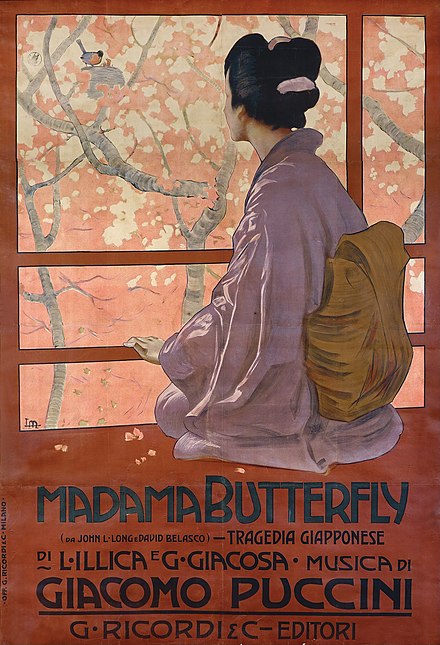

From “Madam Butterfly”

to Vietnam’s Statue of the Awaiting Wife:

Femininity Between two Worlds

“I, the woman of the Orient,

stand between walls of confusion

looking for a way homeward …

I no longer wait for my husband

on top of a lonely mountain,

no longer cradle my child

It is now

that I accept the inheritance

of the warrior’s sword…

But is the sword what I need now,

When there’s no longer a battle of force,

And what to fight for

is what’s left unseen?

Part One:

FROM “MADAM BUTTERFLY”…

- Image of a Butterfly: Stereotype or Complex?

My great love in life is Puccini’s Madam Butterfly. The music is gem-like, of course, but there is also the heart-breaking story of the Asian woman who died for an unworthy Western man who married her in jest, only to leave her in her hopeless illusion of his return.

But Puccini’s notion of tragic femininity that symbolizes the East is not just a vision on stage. In the 20th century, the Korean War, followed by the Vietnam War, produced the “outcast” AmerAsians, stranded on the streets of their motherland. Nonetheless, Puccini’s Butterfly, even when portrayed by a middle-aged opera singer, whose eyelids were painted white to create the illusion of slanting almonds, has come to represent the West’s fascination with Asian femininity.

The image of a butterfly, however, in the literature and philosophies of the East, represents much more than the fragility and elegance of its women. The form of a butterfly is the noble Mandarin’s communiqué to the metaphysical world — the connection between his “self” and a mystical universe. Chuang Tzu, the ancient Chinese philosopher and student of Lao Tzu, once dreamed of being transformed into a butterfly. He wrote his famous books on the cosmos as an exposition of this metamorphic dream.

In Chuang Tzu’s dream, the butterfly is the chosen form to connect man’s physical world with the realm of illusion and spiritual fantasy, where all physical boundaries collapse, and the human psyche becomes free from itself. The butterfly thus symbolizes subconscious creativity, the mystery of night-time darkness enlightened only by the liberation of the self. It is through this process of self-liberation that the human “self” merges and becomes one with the universe. This “merging with the universe” is found in both Buddhism and Taoism, the backbone of East Asian philosophies and cultures.

The butterfly, or the myth it symbolizes, also denotes the most primitive form of literary feminism in the East. Another ancient Chinese writer, Bo Tung Linh[iii] , wrote Lieu Trai Chi Di, [iv] a fantasia-erotica consisting of tales of snakes, foxes, raccoons, and butterflies who transformed themselves into “women” in order to have out-of-wedlock relationships or common-law marriages with men from all walks of life. These “women,” exquisitely beautiful and intelligent, usually possessed black magic administered under a pragmatic, yet coherent, code of ethics that did not conform to the then dominant Confucian values. Free to explore love and a new familial structure, these “women” exerted their individuality and defined their own sense of righteousness and justice. Because they were not entirely human, they were not judged by conventional protocols and moral values.

Yet, in order to promote this new kind of women, Bo Tung Linh had to disguise his heroines as snakes, foxes, raccoons or butterflies, sometimes even as bees, birds and other insects. Bo Tung Linh’s work remains as popular today as in its own time, not only in Chinese-speaking cultures but also in neighboring countries such as Vietnam. Its place in Asian literature, although controversial and therefore may be non-mainstreamed, is indeed undeniable.

The philosophical, spiritual, and feminist significance of the ‘Butterfly” image in East Asian literature, is little-known to the West. Through the music of Puccini, the West is accustomed to equating the Butterfly image with Asian femininity. I call that the “Butterfly Stereotype or Complex.”

This article attempts to explore this stereotype, using examples from American literature and performing arts, from the later part of the 20th century after World War II, to the present day, the first quarter of the 21st century. Tracing back to the 20th century is insightful, considering the significance of the following events in modern history:

–“East” (Asian) and “West”(European-American) cultures met after World War II, following the nuclear bombing and restoration of Japan, as well as the reconstruction of Europe

–racial and gender equality have supposedly come of age in Europe, America, as well as in the changing “Third World”;

–the Cold War and its resulting “proxy” wars in Asia, i.e. Korea and Vietnam, were over, but the atrocities of 9/11 and continuing unrest in the Middle East have signaled the beginning and ripening of other wars and religious conflicts that can deepen a new division between a different “East” and “West”; and

–We now find ourselves in the new virtual world of informational technology, mandating new human resource utilization and allocation.

II. Asian Femininity in the Performing Arts

Take the silver screen from the 20th Century as the first example. Traditionally, we saw Asian women as prostitutes, mistresses, or peasant girls. Five minutes on the screen and they were already made love to, raped, beaten or shot to death. If they were not raped or shot, then they were scheming, conniving, sinister “witches” who aimed to kill, sided with the enemies, or grabbed the dollars!

In post World War II America, Nancy Kwan started what seemed to be a promising film career with the title role in The World of Suzie Wong, co-starring William Holden. Wong was full of character and expression, a definite improvement from the standard cast of witches, prostitutes, peasant girls or laundromat workers, but Wong still represented the West’s fascination with Eastern femininity: from her charm and submissiveness to her darling manipulation to gain the attention of her Western man! Kwan appeared in a few more productions, including the Kung Fu series, but her career was basically short-term. She became the spokesperson for several Asian American causes, giving keynote speeches to Chinese American civic organizations and caucuses. The last time the public saw her (in the 1980s) was in some Asian facial cream commercial.

The 1980s also introduced to Hollywood China-born actress Joan Chen, perhaps the next generation after Nancy Kwan and European import France Nguyen. Chen was the female lead in Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor. Yet, it was dubious whether Chen could entirely escape the “Asian maiden” typecast. During her Hollywood career, Chen was also selected by David Lynch to start in the TV drama series Twin Peak, and then she dyed her front teeth black to star as a countryside Vietnamese mother in Oliver Stone’s Heaven and Earth (another Hollywood stereotypical storytelling of a Vietnamese country girl tied to a post while U.S. and South Vietnamese soldiers stuffed crawling snakes inside her sarong cabaya (áo bà ba) blouse. (The stereotype disregarded the fact that girls from Vietnamese countryside were unlikely to fear snakes. What’s more, in a devastating war where crazy soldiers shot at civilians out of temporary insanity, and rockets blew up people into pieces. No one would have the time and space to direct and arrange such a game of torture. It is confounding how Mr. Oliver Stone, a former Vietnam vet, who had spent enough time in Vietnam to make Platoon, could even improvise and direct such a wooded, unrealistic scene! Apparently, Stone must not have spent enough time in countryside Vietnam, nor did he understand its inhabitants or participate in their daily lives, who definitely were not afraid of snakes. In fact, many of them were experts at snake farms!).

Joan Chen went on to direct a love story starring Richard Gere and Wynona Rider, for which she earned praises and respect, but eventually she got married to a surgeon and returned to her native China to make films.

After 1975, Hollywood produced a number of Vietnam War movies, making them the talk of Hollywood. I have to mention: 1) Deer Hunter with Robert De Niro, the young Merryl Streep, and Christopher Walken, notoriously known for the pathological “Russian Roulette” scene showing how American soldiers cracked up in that foreign guerilla warfare environment, and 2) the famous-infamous Francis Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, scripted after Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

First-generation Vietnamese Americans watching these two movies often walked out of the theater with a dazed or stoned look on their face, the following questions obviously written across their stupefied countenance: “Were they really talking about us Vietnamese in there? Where did all that come from? Our people didn’t have time in the war to hunt for…deer, and who the heck was…Joseph Conrad? ”

My favorite Hollywood portrayal of the Vietnam War had to be Casualties of War, a 1989 drama allegedly based on a true story. I was moved by the film’s humane message cloaked in the image of a compassionate, self-righteous hero portrayed by the wonderful Michael J. Fox. The talented Fox played a lonely yet persevering soldier setting out to save an unlucky Vietnamese girl, carrying out her haunting nightmare back to America and probably for the rest of his life.

But I also have to point out that in Casualties of War, the image of the Vietnamese woman to Hollywood viewers was that of a feeble young girl, kidnapped, battered, abused, raped, stabbed, and then blown up by grenades, despite the hopeless “protection” from her tragic hero. In one scene, Sean Penn lifted the young Vietnamese girl by the neck, the way one would lift a dead chicken.

Regardless of the moral message of the film and its realism value, this meek, pathetic “dead chicken” visual subconsciously shaped the image of Vietnamese women in the mind of American viewers: a victim of war, helpless, even non-human, and lacking identity — Michael J. Fox’s “damsel in distress” had a face (and a body), but she didn’t have a name! She was, indeed, simply…a casualty of war!

Outside of film, in the theater and on stage, since Puccini, throughout the 20th Century, hardly did one ever see an Asian female character. The 1980s and 1990s, however, marked two major productions that revitalized Puccini’s image of Butterfly.

In the late 1980s, the Tony Award went to David Henry Hwang, a second-generation Chinese immigrant, who created a stage production out of the espionage scandal that shocked the diplomatic and international community of the decade. Calling his work M. Butterfly (instead of the former name Monsieur Butterfly), Hwang told the story of a French diplomat who fell in love with a Chinese opera actress, carried on a relationship with her for more than 10 years, only to discover finally that his Butterfly was in fact a man, a Chinese spy. The diplomat had loved, nourished, and perpetuated his own image of the perfect Asian woman, and had carried that illusion into reality. M. Butterfly was eventually made into a Hollywood movie, starring the darkly handsome Jeremy Iron as the diplomat, and sensitive newcomer John Lone as Butterfly. The film’s beautiful cinematography symbolized the romanticized nature of human passion, in the context of the emerging complexity of the West’s relationship with Communist China. Film audience of the 1980s would have to stack M. Butterfly next to the challenging heaviness of political themes entangled in another relationship between two Latin men, expressed in Kiss of a Spider Woman, another controversial stage production (and film), based on a novel by Manuel Puig, the acclaimed Argentine author. (In the film version, William Hurt was cast as a political prisoner, delivering his monologue and dialogue with another prisoner, against a prison wall as his background).

Just like Manuel Puig’s masterpiece, which created the “Spider Woman” motif, Hwang’s work brought us back to the age-old “Butterfly” as a complex thesis, raising perplexing questions about our contemporary life, love, hate, sex, politics, as well as the interplay between East and West, between men and women, between men and men. Hwang recreated the Madam Butterfly syndrome — the stereotype about Asian women — only to challenge and denounce it.

Shortly after Hwang’s success, the Madam Butterfly image was revisited again, this time by London’s musical theater and Broadway. The producers and composers of the musical Miss Saigon never hid the fact that its storyline was a remake of Puccini’s Madam Butterfly. The timing, place and characters had been changed. Butterfly became a bar girl from Saigon. The famous suicidal scene took place somewhere near a tea room in Bangkok. The departing Western lover was a nicer guy, more sensitive perhaps, singing beautiful lyrics about his turmoil and confusion caused by the senseless war thrust upon his existence, contrasted against his tender feelings for the helpless, innocent bar girl with whom he had fallen in love!

But, still, he broke her heart, and, in the end, she, too, died her tragic death.

The racial dispute surrounding the casting of Miss Saigon heightened its popularity. Whether a Filipino actress-singer should be cast as a Vietnamese woman, and whether English Shakespearean actor Jonathan Pryce should be cast as an AmerAsian male caused controversies in the Asian American artistic community. But those controversies should not distract from the real issue: how this multi-million-dollar production portrayed a culture, its history and people on stage.

Surely, the musical was a Western production for a Western public, but Vietnam and its people happened to be the storyline, and the theme of the production! The music was jazzy, with little Vietnamese folk influence, although the talented composer Claude Michel Schonberg did throw in a touch of the pentatonic scale with Asiatic instruments – not enough to change Miss Saigon’s musicality into an Eastern product (it was never supposed to be!). No credit line indicated whether any Vietnamese advisor was ever involved in the production. The few Vietnamese words tossed into the musical were pathetically mispronounced! The costumes did not accurately portray or match Vietnamese attire in the 1970s,the setting for the plot. The only value I found in the musical, other than my enjoyment of its jazzy music and spectacular’ “helicopter” scene, was the fact that Producer Cameron MacKintosh decided to show “real life” slides of the children of Vietnam as a prelude to the musical. Perhaps the collection of millions of dollars out of the Vietnam theme had prompted Miss Saigon producers to display such “social consciousness.” I actually would have preferred that the MacKintosh team started a humanitarian project to help the children of Vietnam.

Miss Saigon’s commercial success centered around its romanticized image of an abandoned exotic bar girl who loved too much for too little, victimized by her devotion to the Western male. The bar was actually a semi-brothel, a symbolic theme that was quite familiar to Vietnamese because of Vietnam’s revered classic Tale of Lady Kieu, an epic story told in verses about a beautiful and talented sixteen-year-old girl who ended up as an abused, mistreated courtesan because she had had to sell herself to save her father from legal problems, a terrible case of injustice.

Miss Saigon, however, was more than just the story of an unlucky courtesan. It was also the Shakespearean theme of Romeo and Juliet, in which Romeo was an American G.I., propagandized by Communist Vietnam as “enemy of the people.” The poor Vietnamese Juliet fell in love with the enemy and, hence, betrayed her people. To pay for her sin, Juliet was doomed to die for the sake of her outcast son. She loved too much for too little, victimized by war and by the passer-by-soldier who was not any better than the invading French legionnaire! As such, Miss Saigon, the revitalized Madam Butterfly, actually also captured a historical event carrying the flavor of international politics.

To be commensurate with such broad-scoped political theme, the musical’s impressive credit was found further in the technically skilled staging of a panicked Saigon in its dying days, signifying the Americans’ seemingly remorseless exit and abandonment of its former ally. Yet, in essence, Miss Saigon was just a tragic love story, with no happy ending. The universality of tragic love and a mother’s sacrifice made the American audience sob.

Beneath all such emotionalism, Miss Saigon was just another version of the West’s fantasy about the myth of the East and its popular manifestation — the binding, unselfish, devoted love and submissiveness associated with Asian femininity. As reborn Madam Butterfly, Miss Saigon confirmed the age-old stereotype about the East. The “East-West” label was repackaged to the approval of the “non-Eastern,” post-Vietnam War audience.

For decades by now, Miss Saigon has been taken “on the road” around the country, creating opportunities for those young Vietnamese teens born in America to try out their singing and acting talents in a role written for a Vietnamese female victim of the war that made her birthplace worldly famous. These young Vietnamese singer-actresses had to fight the cultural bias their parents might still hold against an artistic career, once ridiculed as “classless, at the bottom of society” (xuong ca vo loai), in a traditional Confucian culture like ancient Vietnam, as late as mid-20th century. Those parents might have preferred that their daughter marry well or model themselves into careers such as law or medicine. Yet, such “classless” career required top performing skills, the stamina to perform nightly and to sing at the top of their lungs, plus the courage to play a de facto “prostitute” bearing a child out of wedlock fathered by a foreign soldier who “invaded” her country. (In the bar scene, the main character and her bar “sisters” had to wear what seemed to be a traditional Vietnamese dress, immodestly without the accompanying pantaloons! Such immodesty was totally inappropriate for the Vietnamese culture, but required for the set because the production was…non-Vietnamese, let alone its “semi-brothel” implication!

Many of these young Vietnamese singer-actresses cast in, or competing for, Miss Saigon, outspokenly expressed their dissatisfaction. The dispute today is no longer just about the casting of non-Vietnamese for Vietnamese roles. The degradation of Miss Saigon on the internet seems to express certain cultural complex, crying out for the demand that Miss Saigon be made from the standpoint of Vietnamese Americans, and not just for any audience. I am not ready to say that such an expectation was reasonable. The objectors do not see what I saw as the beauty of Miss Saigon: the jazzy musical score, the hailing of a mother’s love, and the capturing of a tragic historical event on stage. Expressing dissatisfaction does not change the status quo, because the success of Miss Saigon has been a fait accompli, and Broadway musicals are, in my view, “the art and craft of entertainment aimed at a higher class.” The musical has created the career for the talented Lea Salonga, who crossed cultural boundaries by merging the artistic talents of the Philippines with America’s Broadway.

If Vietnamese Americans artists are dissatisfied, they can try creating their own shows, which is the case of the playwright Quy Nguyen, who recently gave the American theater his “rap” play called Vietgone. Yet, Vietgone is an American product just like Miss Saigon, although its creator is Vietnamese American. The play is basically set as a “rap” musical product, full of curse words as well as sexual scenes or innuendos, a 21st century product. Vietnamese who know Vietnam must ask whether such “four-letter-word” realism typified the Vietnamese exodus of 1975, or the mindset of the refugees making such exodus after their country had just collapsed. How likely was it that such sexual language, promiscuity, and the crudity of cursing could occur in front of senior family members like parents or even between lovers in the middle of national tragedies, no matter how confused the mindset had become due to trauma or hopelessness. Did middle-class Vietnamese families and their cultural protocol just deteriorate over night to trigger such heavily expressed sexual crudity, or was such crudity licensed by the playwright as part of contemporary urban America, away from his Vietnamese heritage, in order to please and match the American “rap” culture of the 21st century? The Vietnamese female protagonist, of course, became participant in such crudity that permeated throughout the play. In other words, did Vietgone do any better in portraying the Vietnamese culture in its setting of 1975 than Miss Saigon? Or, was Vietgone’s success largely due to the fact that it is an American contemporary product made exotic and curious by way of a Vietnam-related storyline that brought its audience to a historical event firmly imprinted onto American history?

III. Asian Femininity in Fiction

In the mainstreamed literary arena, throughout the 20th Century, the Asian female, on the other hand, more frequently seemed to occupy a pedestal. But the pedestal itself was also stereotypical. In The Immigrant, Howard Fast’s epic commercial novel of the 1950s (subsequently made into a television drama), the protagonist – self-made millionaire Daniel Lavette – employed a “chink” as his accountant, fell in love with the daughter, and left his beautiful, yet cold Knob Hill wife for the Chinese mistress. The Asian woman taught Lavette cultures and traditions, literatures and myths, human integrity and decency, contrasting against the snobbishness exhibited by his spoiled, aloof, wealthy wife. Finally, it was the Asian woman who took in the empty-handed Lavette when his shipping empire collapsed.

But Lavette’s Chinese mistress was still very much the Madam Butterfly that the West had been accustomed to seeing, except that she was saved from the tragic death. In the beginning, Lavette himself could not decide whether she was attractive in his eyes. Giggling yet serious and intellectual, she was a flat-chested librarian, wearing plain clothes and knowing her place, although that sense of acceptance was always accompanied with great dignity and pride. Like Butterfly, she, too, bore Lavette’s son out of wedlock, enduring her own culture’s rejection. Through it all, she remained the perfect Asian mistress, absorbing, supportive, and wise beyond her years, a building block for the turmoiled, disoriented Lavette.

The Asian female appeared more complex in the work of Nobel-prize novelist Pearl S. Buck. Madame Buck’s Asian female protagonists often exuded intelligence, flexibility, depth, determination, devotion, complexity, and, quite often, a poetic sense of nostalgic self-reflection. Thanks to Madame Buck, who spent the majority of her life in the Orient as missionaries’ daughter, the mysterious China unveiled itself before Western eyes, at a time when Mao Tse-Tung had just closed China’s door to the West. But Madame Buck wrote of Asia, its men, women, and way of life from the perspective of an outsider, one who observed and then related. In the words of the cultural anthropologist, Madame Buck was a participant-observer, but not one who had had to live the experience as a born member of the tribe! The Asian females of Madame Buck were always in control. They asserted themselves in their own Asian way, on their own territory — a transient and changing East facing the foreign West and resisting its influence, while attempting to come to terms with conflicts of cultures. Buck wrote of Chinese and Indian women in China and in India. On their own territory, these Asian females were allowed to be Asian, and in their traditional way, they were masters of their own fate. That context set Buck’s female characters apart from contemporary Asian American women who must truly live a transient and dual role, away from their cultural nest.

Because Madame Buck’s Asian females were portrayed on their own territory, they did not necessarily represent the syndrome that I now call “femininity between two worlds.” Unlike Madame Buck’s Asian females who, at best, were resisting an infiltrating West, the Asian woman in the later half of America’s 20th century often had to play the infiltrating role. She had to first break down the stereotype and prove herself to be different from the stereotype. She then had to open a door, (or should I say crack a wall or an unseen glass ceiling), to gain entry to a world not yet accustomed to seeing the Asian face in any way other than stereotypically.

Quite often, the stereotype was used, not only in preconditioned thinking that evolved into conscious and subconscious social bias, but also by a complete lack of understanding, or an inability to look inside something that seemed so incomprehensible. English novelist Graham Greene articulated this aspect of the stereotype in his 1955 famous novel about Vietnam, The Quiet American:

“…Phuong on the other hand was wonderfully ignorant; if Hitler had come into the conversation, she would have interrupted to ask who he was…She can survive a dozen of us. She’ll get old, that’s all. She’ll suffer from childbirth and hunger and cold and rheumatism, but she’ll never suffer like we do from thoughts, obsessions – she won’t scratch, she’ll only decay…”

Critics have consistently credited Greene’s Quiet American as a prophetic prediction of the outcome of the American involvement in Vietnam, two decades before the war was over. Greene’s political message was flavored by a love triangle between a Vietnamese mistress, a middle-aged English journalist, and a young American diplomat. Greene’s description of the Vietnamese female — the central point of the love triangle – was what I call a “description based on non-description.” The character and personality of the Vietnamese mistress were described entirely through the thoughts and dialogues of her two lovers. To introduce the character, Greene wrote in a cynical way, “Her name is Phuong, or Phoenix, but nowadays, nothing is too fabulous, and nothing rises from the ashes…” Phoenix’s inner world was a mystery to her two lovers and, hence, to the readers. Her two men projected themselves onto her, determining through their own lens of what they thought were her needs.

She spoke very little. Her expressions included a few French words and phrases, “Comment,” (How, What), “Enchanté,” (Delighted), “Je ne comprends pas,” (I don’t understand). Her activities included sitting at a milk bar, going to a French movie, looking at picture books of the English royal family, lighting an opium smoke for her English lover, and readily taking off her black silk trousers, many times even before she was asked. The manifestation of her thoughts consisted of typically a long and hard frown (especially after hearing the news that her American lover had been assassinated), plus her tossing and turning at night as she woke up from bad dreams, quietly explaining to her English lover, “Les Cauchemars,” (nightmares). Her meager belonging consisted of a dozen of colorful scarfs to match her ao dai (the Vietnamese traditional dress), a handful of panties, and perhaps a few French magazines. After the American diplomat died, Phoenix was back with her English lover, bringing with her the scarfs and panties, which Greene described as her “dowry.” Yet, the English journalist (Greene’s alter-ego, perhaps) wrote in a letter to his English wife asking for a divorce, “To part from this woman [Phoenix] to me is the beginning of death.” At some point in the novel, Greene suggested that the English journalist’s love for Phoenix was just another form of his opium addiction, intensified by his loneliness and old, surrendering age.

The character of Phoenix paralleled the incomprehensible nature of the Vietnam War in the eyes of Western observers and participants. The inner world of Phoenix was as impenetrable as the dark tropical jungles of Vietnam to American troops. Perhaps Greene purposefully portrayed the Vietnamese female as a metaphor for the mystery of the Machiavellian political structure of Vietnam, and an unexplainable war that exhausted and bewildered the American mind. But if this was how the West identified the Vietnamese woman, I wonder whether she could ever have any identity independent from the notorious war that constituted an undeniable part of her heritage.

- The Rare Success Story and the Changing Image

In individual cases, 20th Century’s exceptional Asian American women managed to overturn the stereotype. In my early days as a journalism student in the late 1970s, I used to admire newcomer newswoman Connie Chung during the early-morning television news. Chung set her life as a model woman of the 1990s — a successful career in broadcast journalism (which, at one time, made her the main network rival for Barbara Walters); a beautiful woman appropriately demeanored and conservatively dressed to fit the part; a commuting marriage to an equally successful man; and a belated decision to have children. Plus what seemed to be a very strong cultural identity: I read somewhere that during an interview in the earlier stage of her career, Chung once told reporters with a smile, “I am just a nice Chinese girl.”

But, in the 20th century, there was only one Connie Chung in a million. Even today, many other professional women of Asian descent tread the same water for much less glory. Their pain and struggle still go unnoticed. After all, they are the Asian heroines — born with the remarkable quality to smile at fate, die when called for by the Asian code of conduct, absorb pain, devote without qualification, and only tear in silence. Asians have typically been called the “silent minority,” and being vocal is not a favorable cultural trait in the Asian tradition — We don’t ever scream, demand, or attack. (Even the notorious Vietnam War was described as a “passive aggressive” guerrilla war, where innocent civilians and the enemies often became intertwined, interchangeable, and therefore indistinguishable, despite the clear fact that the weapons used were Russian, Chinese, and American!). In ancient days, the ambitious Asian woman traditionally had to hide behind the curtain, behind a “puppet” man through whom she could legitimize her action. Passive aggressiveness had been the mode operandi for the pursuit of any ambition outside of domesticity. For example, the Manchu Empress of China, famous among Western diplomats for her feast of monkey brain, built her political career behind a series of puppet emperors in order to legitimize her political presence.

Since the 1950s, decades went by without any major literary work that focused on the Asian woman. In the 1980s, for the first time, the pain of the Asian American woman was given credence — the dilemma of living between two cultures, haunted by ghosts of the past while growing up American. The decade produced two Asian female writers whose first books each immediately occupied the best-seller list, Authors Maxine Hong Kingston and Amy Tan are both second generation Chinese immigrants. Depicting their relationships with mothers, aunts, cousins, and a whole generation of depressed, suppressed, nostalgic first-generation immigrant women, these two female writers projected their Asian American experience into the mainstream. (It is interesting to note that the Pulitzer Prize in Literature was not awarded to the first Vietnamese American writer until 2015, a man writing about the world of men. Portrayed as “The Sympathizer,” the unnamed protagonist did everything a Vietnamese male had done during the war, and in the diaspora beginning in 1975: he was of mixed blood French-Vietnamese, a double agent working for the communists in South Vietnam, boarding an American plane as an asylee, living among the refugees in the United States, playing in Francis Coppola’s cult film Apocalypse Now, participating in the Vietnamese scheme of “Resistance” to infiltrate back to his native Vietnam for a military “coup” against the Communist government, being caught and imprisoned by the Communist, becoming Boat People for escape, and all other things in between these Rambo-type traumatic adventures. The only thing this archetype of a Vietnamese male did not do was to attend Harvard, Yale, or Stanford to bring pride to his parents, to join the U.S. Army for the Gulf War to show his patriotism as a new American, to become a lawyer or a doctor in America and invest in the stock market to earn a lot of money, to run for the State Legislature or the federal Congress, or to win the Pulitzer Prize recounting his experience (he did not, but his creator – a Race Studies professor, certainly did!).

Perhaps the success of Tan and Kingston in the 1980s had something to do with the fact that by the end of the 20th century, diversity had become increasingly “in vogue” in contemporary America. (For example, in l990, Barbara Bush spoke of diversity during her controversially publicized keynote address at Wellesley College). Or, perhaps the success of Kingston and Tan in the mainstream had something to do with the fact that world trade in the Pacific Rim had become more and more significant and, hence, there emerged the need to understand the Pacific child within the American home base. Perhaps these writers’ success illustrated that the Asian American community was gradually reversing its ‘silent minority’ image. Or, perhaps Kingston and Tan succeeded simply because they expressed universal human emotions and experience that universally touched the human heart, the same way Pearl S. buck had captured universal emotions — issues such as mother-daughter relationships, identity crisis, the past and the present, and the human struggle in between, are of universal appeal regardless of time or cultural divides.

But Kingston’s and Tan’s literary expressions of a painful experience did not substitute for a real systematic support network that was severely lacking for the average, run-of-the-mill Asian female professionals who were frequently forgotten in the American mainstream workforce while American literature was changing its scenery. In the late 1980s, the American Lawyer and the National Law Journal published their surveys on the racial and ethnic makeup of major corporate law firms around the nation. The percentage of Asian female lawyers in these powerhouses was a saddening 0.1 percent. I would not be surprised if the percentage of Asian females in top management positions in Fortune 500 companies would be so small as though non-existent.

Asian female faces perhaps have been more frequently seen in various government entities, in middle-management, or in purely technical and scientific capacities within the private sector. (In the 1990s, the Bush Administration graced Washington’s political arena with two Asian female faces, CFTC Chair Wendy Graham, and Undersecretary of Labor Elaine Chao (who previously had been named head of the Peace Corps). Chao started her career with a White House Fellowship under the Reagan Administration. She was the only Asian female face on the Cabinet during the Trump Administration as Secretary of Transportation. But she, too, has been under scrutiny due to allegations of ethical misconduct. Both Graham and Chao are married to well-known politicians outside of their ethnic cultures. The Clinton and Obama Administrations did not produce any Asian females in cabinet positions, although Obama appointed the first Vietnamese American female federal district judge, and subsequently promoted her to the federal circuit court (this was some eighteen years after my modest appointment to the municipal bench in Houston Texas, making me the first Vietnamese American to join the judiciary; I purposely abandoned the continuing pursuit of a judicial career, in hopes of combining full-time law teaching with creative writing).

In sum, to this day, Asian women who are inspired to be successful professionally are still forced to embark upon a lifestyle, philosophy, and behavior alien to their typically conservative ethnic culture. Often, these women are labeled as having outgrown their culture or having abandoned their roots. Once they have fulfilled their professional goals and reached the top, these women are generally admired by their ethnic community, but within that closed-knit circle, they are also awed and become objects of intense curiosity and envy. Even when a support network is formed, issues discussed often center around the professional endeavors. Issues of cultural identity and the turmoil caused by conflicting cultural values, are often ignored and overlooked, because of their personal and sensitive nature. The “blind spot” often offers as the “alternative reality”: “Oh, everything is fine. We are the superheroines, and we break the norms. No big deal…”

Part Two:

…TO VIETNAM’S STATUE OF THE AWAITING WIFE

Too young to have known North Vietnam in pre-war time, I nonetheless have lived its scenic beauty by reading novels and listening to tales told by my Vietnamese elders. Among the more popular scenic attractions of North Vietnam is a rock that resembles the statue of a woman holding a baby. Standing on top of a mountain, the statue overlooks the bay area that connects mountainous North Vietnam to the South China Sea. The rock has been there for hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of years.[v]

There is a heart-breaking legend in Vietnamese folklore about the rock. I think this folk legend offers an interesting paradox to Puccini’s Madam Butterfly.

In this legend, the female statue was formerly a young woman whose husband had left her to go to war. (The 4,000-year-old history of Vietnam consists of continuing warfare, primarily repeated border wars against China for thousands of years, border wars against southern ethnicities, war against French colonists during the late 19th and first half of the 20th century, and several civil wars in between border wars).

Rearing their child, the woman waited for her husband to return from his exodus, until the wait seemed eternal and she could no longer bear the sorrow.

But she did not give up.

So, one day, she carried the child to the top of the mountain, where she could see the panorama of ships at sea and horses galloping through the forests. The woman stood there, holding her child, waiting for her warrior husband, looking at the sea and forests below so that she could spot him on the day the troops would return. She waited and waited and waited, enduring the wind, the rain, the cold and the heat of seasons. She forgot all concepts of time. She ignored all notions of her surroundings. Day after day, month after month, year after year, she stood there. Eventually, she turned into a stone, a rock, lonely yet persevering, on top of the mountain overlooking the immense sea and forests of North Vietnam.

The Vietnamese gave the rock a name: ” Statue Of The Awaiting Wife.”

Like Puccini’s Madam Butterfly, the female statue of North Vietnam was an awaiting wife, hanging her entire existence on one single hope for her husband’s return. Her hope was, in essence, hopelessness! But the Awaiting Wife of Vietnam was free from the suicidal force of destruction. In fact, her wait caused her to crystalize into eternity. The crystallization signified a spirit so strong, an endurance so vital that the impermanent and perishable human flesh hardened into the more permanent formation of a rock, defying the passage of time and withstanding the test of the environment. The woman’s longing was perpetuated and immortalized; so was her spirit!

Butterfly might have turned herself into a fantasy, a romanticized version of fatal femininity — Butterfly surrendered and took revenge against herself. Her suicide was an egotistical way to cope, as well as her yearning for nobility and perfection, to capture the fantasy of love and make it forever hers.

In the Awaiting Wife of Vietnam, there was no such surrender, nor the notion of egotistical fantasy. Instead, the Awaiting Wife of Vietnam represented eternal will.

Butterfly can be distinguished from the Awaiting Wife of Vietnam in endless ways. For example, while Butterfly was the brutal victim of betrayal, the Awaiting Wife of Vietnam was not. The analogy between Butterfly and the Awaiting Wife of Vietnam can also invoke many arguments, based on comparison or contrast of the Japanese culture vis-a-vis the Vietnamese culture. But that is not the focus here. My purpose is not to compare the Vietnamese culture to the Japanese culture, where suicide carries certain national significance as a noble act.

I am borrowing Puccini’s Butterfly, simply to raise this question: Are we, contemporary Asian American women. still carrying within our mind and heart a little Butterfly, the image though which the world has viewed us, and perhaps the way we have viewed ourselves, ever since our cultures first opened their doors to the West?

EPILOGUE

Asian American women have become the bridge and catalyst between two worlds. In them, the two “labels” – East/West — are combined. If there is one American value that the rest of the world should desire and envy, it is the value of free choice. The existentialist philosopher Jean Paul Sartre of the 20th century viewed choices as the status of “being condemned to be free.” In such a view, if a woman chooses to be Madam Butterfly, she simply cannot fly.

I submit that:

In her newly invented world where East and West must meet and merge, it is Butterfly who must rewrite her image, her ending, and her fate. Her world is no longer a half-moon window overlooking the Pacific Ocean, where she sat demurely, waiting for a ship that would never come. (Or when it did come, it signaled her death!) Butterfly can no longer serve as a fantasy in a world of protocols, traditions, and bias too rigid and ingrained to be broken — a world where her worth is measured by the sacrifices she made for principles not created by her, or for her. Yet, regardless of labels or cultures, sacrifice for a larger cause is always a human virtue – acts of heroism, which very few individuals, men or women, can maintain and live up to.

Of necessity, the world must change because, existentialist or not, the Butterfly, if that’s what she is, must learn to fly instead of waiting demurely to become victimized by the desolation of her wait. My nieces and cousins in California are growing up in a world far different from what faced their mothers decades ago. They will take up their own professional and personal endeavors, perhaps struggling in the clash of culture, still, in an imperfect world, for the same sense of identity that I have sought after.

And, if I must give them some advice, I will simply say this:

As a first-generation Vietnamese American woman in a non-Asian world, if I must discover that the paternal world surrounding me has defined me as an ill-fated butterfly, I shall not fold up to fulfill the curse of tragic femininity and to perfect the fantasy I have been made out to be. If I must struggle to be anything but a butterfly and to take on tasks that seem hopeless, heroine or not, I shall look to the strength and perseverance of the Statue of the Awaiting Wife of North Vietnam, and I must learn the following:

“At times, immortality can only result when the human spirit is measured against

the hopelessness of its endeavors.”

HE END

[i] Wyndi Nicole Duong (formerly Duong Nhu Nguyen) left her native Vietnam in 1975 as a refugee at the end of the Vietnam War. She celebrated her 17th birthday in America. In 1992, she became the first Vietnamese lawyer appointed to the American bench, honored by the American Bar Association as among “pioneer women of color” in the U.S. judiciary. She gave up her law career to travel Asia and to write fiction, a decision that many of her friends consider “lack of wisdom.” In 2013, at the age of 56, she became caregiver for her aging and ailing immigrant parents who passed away in 2018 and 2019, a 24-hour-day-and-night job that many of her friends consider “a status of unemployment leading to impoverished existence in old age.”

[ii] At the audition, Cameron MacKintosh (then a young man) asked me why a lawyer like me would want to sing in Miss Saigon. I told him it was because of “The Rain on The Leaves,” the title of my audition piece, which I sang in both Vietnamese and English. (The Rain on The Leaves, or Giọt Mưa Trên Lá, was written by the Vietnamese songwriter Pham Duy, and performed by him together with Steve Addis in the 1960s under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State). At the Miss Saigon audition before Cameron MacKintosh, I delivered my poem as prelude to the song: “Rain is tears from Heaven, and Leaves are part of the heart of Earth. When Rain meets Leaves, there lies the voice of Miss Saigon. If you put on a stage production about the little woman from Saigon, please think of tears from Heaven falling upon leaves as the heart of Earth.” T

[iii] Vietnamization of the Chinese name.

[iv] Id.

[v] It is believed that many such rocks taking on the shape of a woman holding a child could be found on top of mountain passes along the S-shaped Vietnam peninsula. It is alleged, further, that nowadays, in the 21st Century, the most prominent rock resembling the Awaiting Wife of Vietnam on the northern border between China and Vietnam (provinces of Lạng Sơn/Cao Bằng, Đồng Đăng/Kỳ Lừa), has disappeared. The authorities might have constructed an artificial rock to replace the natural one, in order to keep the legend of the Awaiting Wife alive.

You may like

Translation: The Decision in 2013 of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Certain Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform

Thủ Đức Demonstration High School: A Modern Educational Policy and Teaching Method of the Republic of Vietnam

A Proposed Outline for a Study on Republicanism in Modern Vietnamese History

Tran Le Xuan – Diplomatic Letters

Books for Boys During the French Colonial Period in Vietnam: A Case Study of Huu Ngoc’s Reading Experiences

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Politics & Economy1 year agoRethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education