Phan Van Song, Nguyen Trinh Don, Nguyen Luong Hai Khoi

Examining the “historical evidence” for China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands (Part 3: “China was the first to have development activities on the Nánshā Islands”)

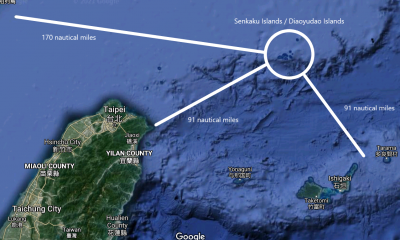

CMOFA cites four ancient books, two from China and the other two from Japan, to claim that China was the first to develop the Spratly Islands as early as the Míng Dynasty.

The two books from China are the 1868 Zhōngguó Hǎi Zhǐnán (中国海指南, China’s Guide to the Sea), and Gèng Bù Lù (更路簿, The Road Book, which has been discussed above). According to CMOFA, there is a description of some sort of activities of Chinese fishermen from Hăinán at some islands of the Spratlys in these books.

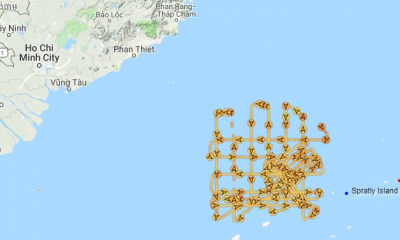

The two Japanese books are the 1918 Boufu Shitou (暴风之岛, Stormy Islands, referred to as “Bàofēng Zhīdǎo” by the Chinese) by Okura Unosuke, and Shinnan Guntou Kaikyou (新南群岛概况, A Survey of the New South Islands [Japanese name for the Spratlys], “Xīnnán Qúndǎo Gàikuàng” by the Chinese). The first book records two cases of Chinese people present at the Cay Islands (Bĕizǐ and Nánzǐ Islands on Chinese) while the second book reports a case of Chinese people doing some cultivation on Thitu Island (Zhōngyè Island in Chinese) in the Spratlys during the authors’ survey in 1933.

These books, especially the two from Japan, indeed give objective records that there were some Chinese people as individuals who did visit and had some kind of activities on these islands, a fact that no one, even the other claimants in the South China Sea, ever denies. However, it should be noted that people from other littoral countries in the region such as Champa, Viet Nam, the Philippines, and Malaysia, or from outside such as Japan, India, the Arabs, and Europe were also present and had activities there even earlier. Particularly, those activities by the Vietnamese people were performed under the Vietnamese State’s assignments which were recorded in many ancient official documents or foreign books. For example, In Đại Nam thực lục toàn biên (大南寔錄前編, Real Records of Dai Nam, volume 1), a chronicle of Viet Nam 1844, and in the 1776 Phủ biên tạp lục (撫邊雜錄, Miscellaneous Records on the Pacification of Frontier Regions) by the Vietnamese scholar Lê Quý Đôn [1], there are detailed descriptions of the geographical situation and natural resources in Hoàng Sa (黃沙, Vietnamese name for the Paracels) and Trường Sa (長沙, the Spratlys), and the exploitation of the Nguyễn Lords over the two archipelagos. It also recorded that Vietnamese people, while doing their assigned activities there, met Chinese fishermen at sea. The 1695 Hǎiwài Jìshì (海外紀事, Overseas Accounts) by the Chinese monk Shì Dàshàn (释大汕) [2] describes regular activities organized by the Viet Nam’s Nguyễn lords (rulers of Southern Viet Nam) in the Paracels and the Spratlys. In Description of Cochinchina by Pierre Poivre (1719-1786) [3] and in an 1849 article by Gutzlaff entitled Geography of Cochin-China Empire in the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, [4] there are also details of Viet Nam administrative activities. These descriptions are backed by many extant official documents of the Nguyễn Dynasty [5] showing that these activities had been done on a continuous basis by the Vietnamese naval forces and fishermen.

For other countries like the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia…there are no historical records of their own. Actually, there are some clues from ancient Chinese books. For example, in Hǎi chá yú lù (海槎餘錄, Extra Records from the Ocean Raft) (ca. 1540), there are descriptions of foreign boats (more likely from Sulu or Brunei) sailing in the Spratlys area. [6]

Therefore, even though the four books cited by CMOFA may be of authenticity and historical significance, let alone these four books appeared quite late compared to the books just mentioned, activities by individual Chinese in the past do not allow for China as a State to assert that it was the first to have development actions in the South China Sea.

Notes

[1] Lê Quý Đôn, Phủ biên tạp tục [tập 1 – phần 1], Nhà xuất bản Giáo dục, 2007 (Nguyễn Khắc Thuần dịch) (Vietnamese). The original traditional Chinese version is available here.

[2] “During the administration of the previous king, every year fishing boats were sent there to collect gold, silver, tools left by shipwrecks at Vạn Lý Trường Sa. In the autumn, the tide is low and runs to the east; big waves could push a boat hundreds of miles off course; the wind force is not so strong, but the danger is always there at Truờng Sa.” (先國王時,歲差澱舍往拾壞船全銀器物雲。秋風潮潤,水盡東回,一浪所湧,即成百里,風力不勁,便有長沙之憂。) 大汕廠翁《海外紀事》,續修四庫全書, v. 744, pp. 665-666

[3] “I have heard that the king sent several vessels every year to the Paracel (Islands) to look for natural curios for his collection. I doubt that this term should be applied to the few branches of black coral, the very ordinary shells, and the few pieces of mother-of-pearl which I was shown.” See Li Tana, Anthony Reid: Southern Vietnam under the Nguyen, Documents on the Economic History of Cochinchina (Dang Trong), 1602-1777. ASEAN Economic Research Unit, Singapore, 1993, p.73.

[4] “We should not mention here the Paracels (Katwang) which approach 15-20 leagues to the coast of Vietnam, and extend between 15°-17° N. lat. and 111°-113° E. longitude, if the King of Cochin-China did not claim these as his property, and many isles and reefs, so dangerous to navigators.… The Annam government, perceiving the advantages which it might have derived if a toll were raised, keeps revenue cutters and a small garrison on the spot to collect the duty on all visitors, and to ensure protection to its own fishermen. Considerable intercourse has thus gradually been established and promises to grow in importance on account of the abundance of fish that come to these banks to spawn. Some isles bear stunted vegetation, but freshwater is wanting, and those sailors who neglect to take with them a good supply are often put to great straits.” See Gutzlaff, Geography of Cochin-China Empire, Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol.19, 1849, p.93.

[5] Monique Chemillier-Gendreau, Sovereignty over the Paracel and Spratly Islands, Springer, 2000

[6] “Wànlǐ Cháng tí (Spratlys) opened to the south, the waves moved strongly and then returned, accidentally sliding into it, no one could escape. Foreign boats are familiar [with the area], can avoid, even in strong winds without worries.” (萬里長提出其南,波流甚急,再入回留中,未 有能脫者。番舶久慣,自 能避,雖風況亦無虞). See《中國南海諸群島文獻彙編之一:西陽雜姐,諸番志,島夷志略,海槎餘錄》,臺灣學生書局,pp. 407-408.

Related articles

Examining the “historical evidence” for China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands (Part 1: “China was the first to discover and name the Nánshā Islands”)

Examining the “historical evidence” for China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands (Part 2: Chinese official maps and historical/geographical books against China’s claim in the South China Sea)

Examining the “historical evidence” for China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands (Part 3: “China was the first to have development activities on the Nánshā Islands”)

Examining the “historical evidence” for China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands (Part 4: “China was the first to exercise jurisdiction over the Nánshā Islands”)

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago