Phan Van Song, Nguyen Trinh Don, Nguyen Luong Hai Khoi

Examining the “historical evidence” for China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands (Part 2: Chinese official maps and historical/geographical books against China’s claim in the South China Sea)

Although the modern Chinese State insists on having ample historical evidence to back up its claim over the South China Sea islands, there exist many official maps and historical/geographical books that demonstrate otherwise. Unsurprisingly, these are completely ignored by the Chinese government and a great many of its citizens.

Examples of such books include Dà Yuán Yītǒng Zhì (大元一统志, Comprehensive Geography of the Great Yuán), Dà Míng Yītǒng Zhì (大明清一统志, Comprehensive Geography of the Great Míng), Dà Qīng Yītǒng Zhì (大清一统志, Comprehensive Geography of the Great Qīng), and Qīng Shǐgǎo (清史稿, History of Qīng). In these texts, one could not find any locations with the names Shítáng/Xīshā (the Chinese name for the Paracels), or Chángshā/Nánshā (the Spratlys), or any similar names [1]

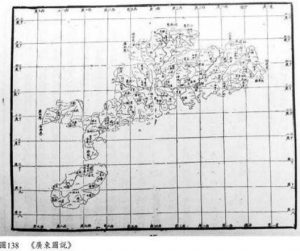

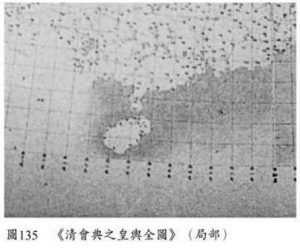

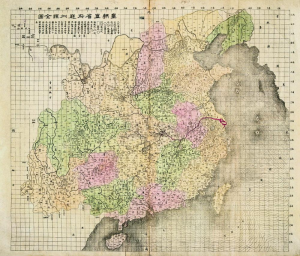

As for China’s historical official maps, plenty is consistent with the historical official texts in that China’s territory does not go beyond Hăinán Island to the south. Such maps include Máo Kūn Tú (茅坤图, Máo Kūn Map) [2] – published in the late-Míng Dynasty military encyclopedia Wǔ Bèi Zhì (武備志) with an archaic copy held in the US Library of Congress in Washington DC; Huáng Yú Quán Bǎntú (皇舆全版图, Imperial Complete Map) – published under the command and instruction of the Qīng Dynasty’s Emperor Kāngxī (康熙) with copies available at the University of Tōkyō; Guǎngdōng Túshuō (廣東圖說 1866, Complete Illustrated Map of Guǎngdōng 1866) – published by the Guǎngdōng Province Government (Figure 2); and especially Qīng Huìdiǎnzhī Huángdiǎn Yútú 1899 (清会典之皇舆全图 1899, Complete Imperial Map of the Qīng 1899) – a very authoritative map published by the Qīng Dynasty’s Central Government (Fig. 3).

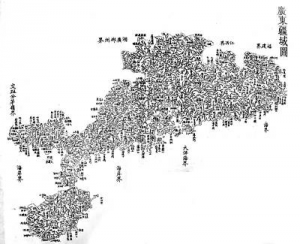

Fig. 2. Guǎngdōng Túshuō (廣東圖說 1866, Complete Illustrated Map of Guǎngdōng 1866) [3] does not show any territories belonging to Guǎngdōng Province beyond Hăinán Island. (Source: The National Library of Australia and 黎蝸藤, 被扭曲的南海史: 二十世紀前的南中國海, 出版社:五南, 2016, p. 448 [Lí Wō Téng, “Distorted History of the South China Sea: the South China Sea before the 20th Century”, Wǔnán Press, 2016, p. 452])

Fig. 3. Complete Imperial Map of the Qīng 1899 (partial) [4] shows Hăinán Island as China’s southernmost territory. (Source: 黎蝸藤, 被扭曲的南海史: 二十世紀前的南中國海, 出版社:五南, 2016, p. 448 [Lí Wō Téng, “Distorted History of the South China Sea: the South China Sea before the 20th Century”, Wǔnán Press, 2016, p. 448])

Pham Hoang Quan, an independent researcher in Viet Nam, pointed out in 2007 that all Chinese official maps published before the First and the Second Republic of China do not show any territories further than the Hǎinán island.[5]

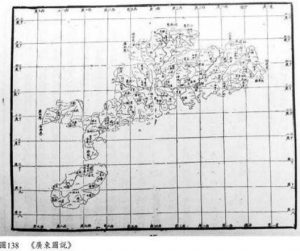

The Gǔjīn Túshū Jíchéng (古今圖書集成, Complete Collection of Illustrations and Writings from the Earliest to Current Times) is the Imperial Encyclopedia containing 10,000 volumes, written during the Qīng Dynasty’s emperors Kāngxī and Yōngzhèng, completed in 1725. This Imperial Encyclopedia has three maps relating to the southern Qīng territory that does not show any archipelagoes further than Hǎinán island as we know today. These maps are Zhífāng Zǒngbùtú (職方總部圖, General Map of Administrative Units), Guǎngdōng Gāngyùtú (廣東綱域圖, Guǎngdōng Area Map), and Qióngzhōufǔ Gāngyùtú (瓊州府綱域圖, Qióngzhōu prefecture area map), and are included in Zhí Fāng Diǎn (職方典, Official Book on the Map of Administrative Units), the first volume of this Imperial Encyclopedia).

Zhífāng Zǒngbùtú [職方總部圖, General Map of Administrative Units]

Guǎngdōng Gāngyùtú (廣東綱域圖, Guǎngdōng Area Map)

Qióngzhōu-fǔ Gāngyùtú (瓊州府綱域圖, Qióngzhōu Prefecture Area Map)

(Source: “Qīndìng gǔjīn túshū jíchéng, fāng yú huìbiān, zhí fāng diǎn” 『欽定古今圖書集成』, 方輿彙編, 職方典 (“Complete collection of Ancient and Modern Pictures and Books by the Imperial Order”, Edited by Chen Menglei 陳夢雷, Jiang Tingxi 蔣廷錫 Qing Dynasty mandarins. An online version is available here)

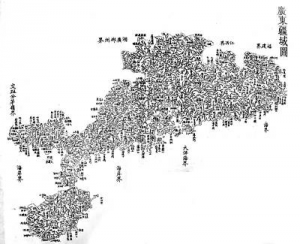

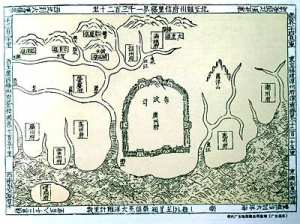

The map of Guǎngdōng province in the book Guǎngdōng Tōngzhì (廣東通誌, Gazetteer of Guǎngdōng Province) written and revised six times from the Míng Dynasty (1535) to the Qīng Dynasty (1822) by local officials shows only the Qióngzhōu (瓊州) island (Hǎinán today). This map, shown below, is reprinted in the book “Guǎngdōng Lìshǐ Dìtú Jíbiān Wěihuì ‘Guǎngdōng Lìshǐ Dìtú Jí’, Guǎngdōngshěng Dìtú Chūbǎnshè 1995 nián” (廣東歷史地圖集編委会、『廣東歷史地圖集』、廣東省地圖出版社、1995年: The Editorial Board of the Guǎngdōng Province’s Collection of History and Geography, “The Collection of History and Geography of Guǎngdōng “, Guǎngdōng Province Map Press, 1995).

Pham Hoang Quan pointed out that it is valuable to note that this map was drawn about one hundred years after Zhèng Hé (鄭和) had commanded over the final expedition into the Indian Ocean (then referred to as “Western Ocean” in China) in 1430. During those 100 years, the Míng Dynasty did not establish sovereignty (even only on a map) over the places where they invested in exploration.

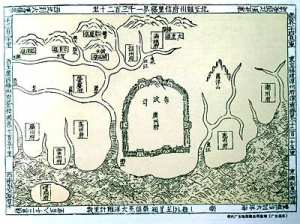

The Qīng Dynasty’s scholar-official Wèi Yuán (魏源) published the book Hǎiguó Túzhì (海國圖志, The Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Countries) in 1842, describing the geography of foreign countries. Based on their names, three of the maps included in the book are about Viet Nam and are reproduced here. (Source: 魏源, 海国图志, 岳麓书社出版, 2011年 [Wèi Yuán, The Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Countries, Hunan Yuelu Publishing House, 2011])

“Map of the State of An Nam” (安南國圖 “Ānnán Guótú”)

“The Map of Southeastern Coastal States” (東南洋沿海各國圖 “Dōngnányáng Yánhǎi Gèguó Tú”), in which the South China Sea is referred to as “Southeast Sea” (東南海).

The “Map of the Changing Boundaries of the States in the Southeast Sea” (東南洋各國沿革圖 “Dōngnányáng Gèguó Yángétú”).

The third map, “Map of the Changing Boundaries of the States in the Southeast Sea” (東南洋各國沿革圖), mentions the islands named “Wànlǐ Chángshā” (萬里長沙, “Vạn Lý Trường Sa” in Vietnamese) and “Qiānlǐ Shítáng” (千里石塘, “Thiên Lý Thạch Đường” in Vietnamese) in “The East Ocean” (東洋大海) that are showed in the east of Viet Nam’s Eastern capital (越南東都) and Viet Nam’s western capital (越南西都).

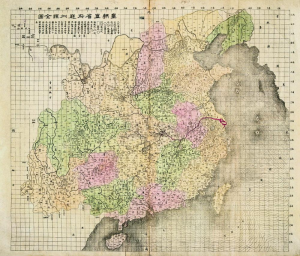

Besides, Huángcháo Zhíshěng Dìyǔ Quántú (皇朝直省地與全圖, Complete Map of All Provinces of the Empire) published by the Qīng Dynasty in 1904 shows that the southernmost part of China’s territory in 1904 is Qióngzhōufǔ (瓊州府) that is now on Hǎinán Island. (An online version of this map is available here)

Besides, 皇朝直省與地全圖 (“Qing Empire’s complete map of all provinces”, Published by China: s.n. Guangxu bing shen 1896) and 皇朝直省與地全 (“Qing Empire’s complete map of all provinces”, Published in Shanghai: Xujiahui tian zhu tang, Guangxu ding hai [1887]) also express China’s southernmost tip as Hainan island. (Source: Library of US Congress 皇朝直省與地全圖 1896 and 皇朝直省與地全圖 1887)

In summary, China’s administrative maps before the early Republic of China do not include any islands further to the south than Hǎinán island. Thus, before the early Republic of China, in the perception of both Chinese central and local administrations, the Paracel and Spratly Islands in the South China Sea were not considered as China’s territory. The Chinese State then did not demonstrate any attempts or efforts of governing them as claimed by the Chinese State now.

Furthermore, one should take into account the history of sea travel in the whole region to evaluate China’s claim. Many other nations might have known of the South China Sea islands long before the Chinese. For example, Nhật Nam (日南, referred to as “Rìnán” by the Chinese) (now Quảng Nam Province in central Viet Nam) was contacted by Roman envoys in 166 CE [6]; and Óc Eo (now in southern Viet Nam) appeared to be a busy port of the Kingdom of Fúnán between the 1st and 7th centuries CE, and had been known of by the Romans, Persians, Indians, and Greeks [7]. In addition, the Cham people, a Malayo-Polynesian ethnic group, the owner of the Champa kingdom, now residing in southern Vietnam, came to mainland Southeast Asia from Borneo [across the South China Sea] in the era of Sa Huynh culture in the 2nd and 1st century BC [8]. It is very likely that these peoples had crisscrossed the South China Sea and discovered its islands before the Chinese people did.

As the historical documents do not support China’s role in discovering the Paracels and the Spratlys, the claim that it was the first to name these islands is even more implausible. In fact, CMOFA does not present any particular pieces of concrete evidence from history other than a few Chinese names such as “Zhănghăi”, “Qítóu”, “Shítáng”, and “Chángshā” throughout its ambiguous arguments. [9]

Also, the Chinese naming system for the Paracels and the Spratlys is mostly based on the translation or phonetic conversion of the corresponding English names. Examples of name translation include Bĕi Dăo (北島) for North Island, Shí Dăo (石島) for Rocky Island, Nánshā Zhou (南沙洲) for South Sand, and Jīn yín dǎo (金银岛) for Money Island [10]. Transliterations names include Ānbō (安波) for Amboyan Cay, Xīdù (西渡) for Dido Bank, Mĕngzì (蒙自) for Menzies Reef, Àoyuán (奥援) for Owen Shoal, Pāilāsū (拍拉苏) for Paracels and so on. With these striking parallels it is unsubstantiated that the Chinese names appeared before the English names, and so is the claim that China was the first to name the features in the South China Sea.

Notes

[1] Hồ Bạch Thảo, Xisha (Paracel) and Nansha (Spratly) referred to as Chinese land in Qīng Shǐ gǎo and Dà Qīng yī tǒng tiān xià quán tú? available at here (Vietnamese).

[2] See The Library of Congress

[3] See 黎蝸藤, 被扭曲的南海史 (The Distorted History of the South China Sea before 1900), 五南, 2016, p.452.

[4] See 黎蝸藤, 被扭曲的南海史 (The Distorted History of the South China Sea before 1900), 五南. 2016, p.449.

[5] Pham Hoang Quan, “Paracel and Spratly islands in Chinese historiography”, Talawas Journal, December 11, 2007 (Vietnamese language)

[6] Hou Han Shu, The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu

[7] Higham, C., Early Mainland Southeast Asia, Bangkok: River Books Co., Ltd., 2014, p 279

[8] Higham, C., Early Mainland Southeast Asia, Bangkok: River Books Co., Ltd., 2014, p 317

[9] See also Johannes L. Kurz, The South China Sea and How It Turned into “Historically” Chinese Territory in 1975, available at here.

[10] As recent as April 19, 2020, China still used the name of the superintendent of the Bombay Marine, William Taylor Money, to name a low tide elevation which is in the east of Money Island as Jīnyíndōng dǎo (金银东岛, East Money Island).

Related articles

Examining the “historical evidence” for China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands (Part 1: “China was the first to discover and name the Nánshā Islands”)

Examining the “historical evidence” for China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands (Part 2: Chinese official maps and historical/geographical books against China’s claim in the South China Sea)

Examining the “historical evidence” for China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands (Part 3: “China was the first to have development activities on the Nánshā Islands”)

Examining the “historical evidence” for China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands (Part 4: “China was the first to exercise jurisdiction over the Nánshā Islands”)

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

After 19752 years ago

After 19752 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy6 years ago

Politics & Economy6 years ago

Society & Culture6 years ago

Society & Culture6 years ago

ARCHIVES6 years ago

ARCHIVES6 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Vietnamese-America5 years ago

Vietnamese-America5 years ago