Society & Culture

Creation, Organization and Use of Recorded Information On Overseas Vietnamese Experience

Published on

By

Lam Vinh The

INTRODUCTION

The Republic of Vietnam, i.e., South Vietnam, officially ceased to exist at 12 noon, April 30th, 1975 after its last President, General Duong Van (Big) Minh surrendered to a high-ranking army officer of the North Vietnamese troops at the Dinh Doc Lap (Independence Palace). About 132,000 South Vietnamese were successful in getting out of the country either by their own means or being evacuated by the Americans.[1] By March 1996, almost one million Vietnamese have settled in the United States.[2] In Canada, the total number of Vietnamese was 136,810 in 1996.[3] There are also important Vietnamese communities in Western Europe and Australia. A significantly large body of recorded information has been generated by the Vietnamese expatriates throughout the world. This paper tries to summarize some of the important issues in the creation, organization, and use of that body of recorded information.

CREATION OF INFORMATION BY OVERSEAS VIETNAMESE

In this paper, the term “information” is used in its broadest meaning to include all kinds of communication messages regardless of contents and formats, with a focus on the printed word. Due to the author’s limitations, however, all data used will be from North American sources only.

The generation of information by overseas Vietnamese was something destined to happen. Like any other groups of people in exile, the Vietnamese came to their adopting countries with heavy baggage of their past. It would be essential, therefore, to understand the motivation of the overseas Vietnamese before we can appreciate what they produce. Generally speaking, the Vietnamese now living in the United States came to this country in three waves: the 1975 evacuees coming right after the collapse of South Vietnam, the “boat people” coming in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, and, finally, the HO (Humanitarian Operation) Program people coming after 1990.[4]

1975-1979 Period

The 1975 group, including a large number of high-ranking government officials and armed forces officers, represented more or less the people who were decision-makers and responsible for the war efforts. They felt an obligation to defend what they did in the past that led to the collapse of the country. The U.S. government, especially those in the military circle, also wanted to know why the war was lost. So, either by their own initiative or through financial support from the American government, these people have written about their own experiences. The most important publications during this period were the issues of the monographic series titled “Indochina Monographs” published by the U.S. Army Center of Military History.[5] Also published during this period were Vice-President Nguyen Cao Ky’s Twenty Years, Twenty Days, by Stein and Day in 1976, and General Tran Van Don’s Our Endless War: Inside Vietnam, by Presidio Press in 1978. The publications in Vietnamese language of this period were mostly reprints of works that had been published in South Vietnam before 1975. There were only a handful of new Vietnamese language publications written by a few authors–e.g., Võ Phiến and Lê Tất Điều– whose names had already been established before 1975. Their works reflected their state of shock by the sudden uprooting and their loving memories of the fatherland, now forever lost. A mere total of 40 serials, i.e., magazines, newspapers, newsletters, and occasional papers as well, were published between 1975 and 1979. It is, however, worth noticing that the first newspaper, Chân Trời Mới (New Horizon), had its first issue published on May 2nd, 1975 when this first wave of Vietnamese were still in the refugee processing center in Guam.[6]

1980-1990 Period

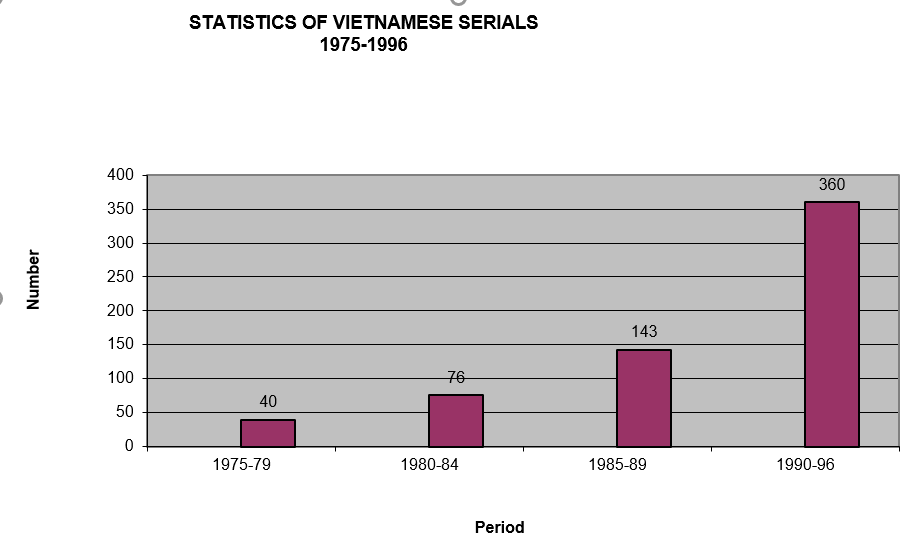

The whole picture changed radically with the second wave of refugees, which added hundreds of thousands of people to the Vietnamese communities. This important influx of Vietnamese refugees provided a big boost to the whole process of generation-dissemination-consumption of recorded information. By 1990, it was estimated that there were “hàng chục tổ chức văn hóa, trên năm mươi nhà xuất bản, hàng trăm tờ báo đang hoạt động, hang ngàn người cầm bút và hơn một triệu người đọc” (dozens of cultural organizations, over fifty publishing houses, hundreds of published serials, thousands of writers, and over one million readers)[7] Between 1975 and 1996, we witnessed a strong and steady growth of the number of published Vietnamese-language serials as reflected in the following figure:

Figure 1 Source: A Bibliography of Overseas Vietnamese Periodicals and Newspapers, 1975-1995 = Mục Lục Báo Chi Việt Nam Hải Ngoại, 1975-1995 / compiled by Nguyen Hung Cuong & Nguyen Anh Tuan. Washington, D.C: Southeast Asia Resource Action Center, 1997.

Unlike the 1975 evacuees, the “boat people” had had some painful living experiences with the Communists before they left Vietnam. Besides, they were more “ordinary” people than the original evacuees; even if they had worked for the government, they were holding lower ranks. Their motivation, therefore, was totally different from the first group. They did not feel obliged to defend their pre-1975 activities. At the same time, they were angry by the way the Communists had treated them: internment in labour camps, confiscation of their properties, forced relocation in “new economic areas”, etc. Let’s hear from the author Võ Phiến, commenting on the difference between the two groups: “Lớp tháng tư, tháng năm 1975 ra đi trong cảnh tan tác đổ vở, mang tâm trạng tuyệt vọng; lớp ra đi sau 77, 78 đã trãi qua đàn áp nhục nhã mang theo cái uất hận của đồng bào trong nước dưới chế độ mới. Lớp trước ưu hoài; lớp sau sôi sục. Lớp trước bi; lớp sau phẩn. Lớp trước bùi ngùi về cái Việt Nam trước 75; lớp sau hậm hực về cái Việt Nam sau 75” (The April, May 1975 group, leaving amid devastation, are desperate; the after-77, 78 group, having gone through humiliation and oppression, are bringing with them the anger of their fellow countrymen living under the new regime. The former group longs for the past; the latter one boils inside. The former group is pessimistic; the latter one is angry. The former group is melancholic about the Vietnam before 75; the latter one is upset by the Vietnam after 75)[8] This group of Vietnamese identified themselves more as political refugees. Also, unlike the 1975-79 period, this period has witnessed the appearance of a whole generation of new writers, especially female writers and the Vietnamese literature created during this period was indeed “a literature in exile”. Both production rate and volume of recorded information during this period was incredibly tremendous. Nguyễn Ngọc Bích, in his paper “Vi Trí Trung Tâm Của Văn-Học Việt-Nam Hải-Ngoại” (The Central Position of the Overseas Vietnamese Literature), made the following comments: “…sự phong phú khác thường của nền văn-học Việt-Nam hải-ngoại trong những năm vứa qua, đặc biệt là trong thập niên 1980, và phải kể như bột-khởi từ năm 1985 trở đi …” (…the extraordinary abundance of the overseas Vietnamese literature in the past several years, especially in the 1980s, and more specifically the great boost after 1985…); “Hàng trăm tác-phẩm đáng kể trong một nửa thập niên thì trong một quốc gia bình-thường cũng đã là một điều đáng mừng rồi. Nửa là đây, ta đang nói về một nước Việt Nam lưu vong mà con số không lên quá một triệu người rải rác khắp năm châu” (The publication of hundreds of important works in half a decade, in a country in normal conditions, should already be something to celebrate. It should be a lot more important in this case since we are talking about a Vietnam in exile whose population does not exceed one million and is scattered throughout the whole world)[9] The 1985 boost was confirmed by Nguyễn Hùng Dũng when he reviewed the situation in 1986: “1986, năm đầu thập niên thứ hai của người Việt tị nạn cũng là năm mà văn hóa Viêt Nam hải ngoại phát triển mạnh mẽ hơn hẳn đầu thập niên trước và những xuất bản phẩm của người Việt tị nạn trở nên phong phú, trong đó có nhiều tác phẩm lớn của các nhà văn, nhà thơ cũ và mới đã đặt chân tới bến tự do sau ngày miền Nam VN sụp đổ” (1986, the first year of the second decade of the Vietnamese refugees, is also the year in which the overseas Vietnamese literature has strongly developed, clearly exceeding the first years of the previous decade; and the publications of the Vietnamese refugees have become abundant with important works by old and new writers and poets, who have set foot on the land of freedom after the collapse of South Vietnam).[10] While the high-ranking South Vietnamese government officials and military personnel continued to publish accounts of their pre-1975 activities, a large majority of writers of this period talked about their post-1975 experience. Many important autobiographical works were published with a strong focus on the painful experiences endured in re-education concentration camps. The tremendous growth of the literature in exile during this period can be explained by many factors: 1) Contributions were made not only by a whole generation of new writers but also by pre-1975 writers who succeeded in their escapes from Vietnam; 2) Vietnamese fonts were available with personal computers, making page layout with Vietnamese diacritics easier and faster; and, 3) The presence of a large community made publishing and selling books reasonably profitable businesses. Let’s hear from Võ Phiến: “Tạp chí văn học ở Sài Gòn trước 1975 ấn hành trung bình mỗi kỳ chừng năm nghìn bản, ở đây hiện nay vào khoảng một nghìn bản. Một nghìn bản cho một triệu người, so với năm nghìn bản cho hai chục triệu người: cao hơn gấp bốn lần. Sách còn cao hơn: ở Sài Gòn sách in nghìn rưởi hai nghìn cuốn; ở đây từ một nghìn đến nghìn rưởi cuốn. Số lưu dân Việt Nam ít hơn dân số Miền Nam hai mươi lần mà số sách tiêu thụ chỉ xê xích chừng ấy, thật là điều không ngờ.” (Before 1975, literary magazines published in Saigon had an average run of 5,000 for each issue, here right now each run is about 1,000. One thousand copies for one million people, compared with 5,000 for twenty million: four times more. The ratio is even higher for books: in Saigon books were issued between 1,500 and 2,000 copies; here it is between 1,000 and 1,500. The population in exile is only one-twentieth of the population of South Vietnam and yet the volume of books sold is almost the same, this is really incredible).[11] By 1986-87, the overseas Vietnamese communities were provided with almost every category of literary forms in significant volume: biography, short stories, novels, poetry, history, literary history and criticism, etc. (Nguyễn Ngọc Bích has also written several excellent annual summaries of overseas Vietnamese literary activities.) [12, 13, 14]

Post-1990 Period

The HO group came to the U.S. in very special circumstances: the automatic acceptance of “boat people” as legitimate political refugees was ended with people still in “refugee” camps in South East Asia having to go through the screening process; the collapse of the Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies; the policy change in Vietnam paving the way for the possible return to Vietnam for the Vietnamese expatriates; the emerging movement of cultural exchange between Vietnam and the overseas Vietnamese community. All of these created an uneasiness within each expatriate: when you are no longer banned from returning to your country, are you still an exile? A Vietnamese literary critic, Nguyen Hung Quoc, observed that “Từ khoảng 1989, 1990 trở đi, như sự nhất trí của mọi người, văn học lưu vong bước vào giai đoạn bế tắc.” (From 1989, 1990 onward, as everyone has agreed, the literature in exile has stepped into a deadlock period).[15] This phenomenon had been predicted by Võ Phiến in 1987: “… không có một tương lai xa cho nền văn học này. … Những em bé cháu bé lớn lên ở Mỹ, sử dụng tiếng Mỹ thạo hơn tiếng Việt, được đào tạo từ bậc mẫu giáo ở trường Mỹ, ra đờI, chúng có thể là mầm non của nền văn-học bằng Việt ngữ được sao ?” (… there is no distant future for this literature. … The children who grow up in the United States, being more fluent in English than in Vietnamese, starting in kindergarten and going through the whole educational system in American schools, going into adult life, cannot be the source of this literature in Vietnamese, can they?).[16] These predictions were confirmed in 1992 by Nguyễn Hoàng Nam, who wrote: “Nhìn chung năm 1992, ngành xuất bản sách xuống dốc và sẽ xuống dốc nữa… , năm 1992, ngườI ta đã thấy dấu hiệu của một sự phá sản… Với cái đà này, tương lai không có gì sáng sủa trong sinh hoạt văn nghệ ở hải ngoại.” (In general, in 1992, the book publishing activity has gone down and will go down even further…, in 1992, we begin to see signs of a bankruptcy… With this trend, the future of overseas cultural and literary activities is not bright).[17] Võ Phiến, Nguyễn Hưng Quốc and Nguyễn Hoàng Nam may be right in their observations vis-à-vis the body of literary works in Vietnamese language, especially creative literary works. But in other categories of recorded information, especially the research-oriented materials, information in English language and the online information (for both English and Vietnamese languages), the growth continued and in exponential proportion. From 1995-1999, production output of overseas literature did not show any sign of slowing down. On the contrary, we witnessed a steady growth of overseas literature, in particular in the category of newspapers. The most significant increase in newspapers happened in Eastern Europe. Nguyễn Ngọc Bích has observed: “Đã có lúc con số những báo loại này lên đến gần 100 tờ khác nhau.” (There was a time when the number of such newspapers went up to almost 100 different titles).[18] The 2000 catalog of Đại Nam publishing house, the largest Vietnamese publisher in the United States, listed more than 2000 titles, of which 296 were post-1975 publications. There are now thousands of websites on the INTERNET covering almost every aspect of the overseas Vietnamese experience. (See Appendix B for a selected listing of important websites). At the same time, production and sale of non-book materials, such as music video tapes, cassette tapes and CDs, and quite recently, talking books, continued to grow. By 1991, in the United States alone, there were 12 Vietnamese-language television programs19.

ORGANIZATION OF RECORDED INFORMATION

Gathering Information

Efforts in preserving this body of recorded information have been carried out by various organizations/institutions, mostly located in the United States. Mr. Nguyễn Hùng Cường, former Deputy National Librarian of the Republic of Vietnam, has identified these information-gathering institutions in his well-researched paper “Tài Liệu Việt Học Tại Các Thư Viện Lớn Và Trung Tâm Việt Học” (Vietnamese Studies Documents at Large Libraries and Vietnamese Studies Centers) presented at the National Congress of Vietnamese in America, held in Washington, D.C., August 1987.[20] In the United States, these institutions are:

- Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.;

- Cornell University Libraries, Ithaca, New York;

- Yale University Library, New Haven, Connecticut;

- Harvard-Yenching Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts;

- Southern Illinois University Morris Library, Carbondale, Illinois;

- University of California at Berkeley General Library, Berkeley, California;

- University of Hawaii Library, Honolulu, Hawaii;

- George Mason University, Indochina Institute, Fairfax, Virginia;

- Vietnamese Studies Document Delivery Center, San Jose, California; and,

- Indochina Resource Action Center (IRAC, later changing name to SEARAC, South East Asia Resource Action Center), Washington, D.C.

It should be noted that the Vietnamese holdings of these institutions are largely pre-1975 publications. We should now add to the list:

- Vietnam Center of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, which now houses the collections of the Indochina Archive transferred from UC Berkeley.

- University of California, Irvine, Southeast Asian Archive

- University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

- University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

In addition to these important institutions, most public libraries in American and Canadian cities where there is a sizeable Vietnamese community also have Vietnamese-language materials in their collections. In the United States, Los Angeles and Orange County public libraries have a large collection of Vietnamese-language publications. In Canada, the Montreal public library system has about 6,000 Vietnamese titles accessible through its Merlin OPAC (http://merlinweb.ville.montreal.qc.ca:1080/cgi-bin/bestn?id=%act=23%lang=1)

Organizing Information

Attempts have been made at these information-gathering institutions to make their Vietnamese holdings accessible to users. The most important effort was carried out by the Library of Congress in the publication of its Vietnamese Holdings in the Library of Congress: A Bibliography (1982) and Vietnamese Holdings in the Library of Congress: Supplement, 1979-1985 (1987). These two bibliographies are, however, heavily slanted toward North-Vietnamese publications and materials published in South Vietnam before 1975: in terms of monographs, the 1982 bibliography contains 1552 entries for South Vietnamese entries out of a total of 2902 (53.48%); the 1987 bibliography is even worse, listing only 439 entries out of a total of 1795 (24.45%), and among these 439 entries only 256 are for materials published after 1975.

Figure 2 Source: United States. Library of Congress. Vietnamese Holdings in the Library of Congress : A Bibliography, 1982, and Supplement, 1979-1985.

As mentioned above, the generation of recorded information of the overseas Vietnamese increased tremendously after 1985. These two Library of Congress bibliographies, therefore, are not very useful. The Library of Congress has not published any further supplements since then. Other Vietnamese (or Southeast Asian) Studies centers have also published bibliographies based on their holdings. Even some public library systems have done the same thing. In general, however, there are not too many bibliographies available on Vietnamese materials. The main reasons for this lack of enthusiasm in publishing printed bibliographies are: first, it is too expensive (and the 1990s was a decade of financial restraint for libraries, even for the Library of Congress); second, the appearance of the OPACs (online public access catalogs) makes information retrieval a lot easier than it used to be in the past; third, the INTERNET and Web technologies now make information provision and exchange not only easier but also a lot faster. This could hold true for experienced library users but this could present many difficulties for ordinary people. Not all library systems, especially public libraries, are Z39.50-compliant and that requires that the users have to know the information retrieval syntax used by different systems. In addition, almost all North American library systems cannot display Vietnamese diacritics. In many instances, the Vietnamese users cannot tell if the OPAC records displayed really are for the books they are searching. (See Appendix A for a selected bibliography of bibliographies).

Documenting The Experience

There have been numerous efforts to document the overseas Vietnamese experience. In Canada, an exhibition titled “Boat People No Longer: Vietnamese Canadians” was opened on October 16, 1998 at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Hull, Quebec (URL: http://www.civilization.ca/membrs/traditio/vietnam/viint00e.html). The exhibition was introduced in the Museum’s Communique as follows: “More than 400 artifacts representing the various aspects of the lives and traditions of the Vietnamese in Canada made up Boat People No Longer: Vietnamese Canadians, filling 5,000 square feet of exhibition space in the Arts and Traditions Hall. Members of the Vietnamese community in Canada have generously loaned numerous objects in the exhibition, which is divided into five categories based on the following themes: historical context; arrival of the boat people in Canada; community, family and religion; cultural traditions; adaptation to change, and contributions of the Vietnamese to this country”. In the United States, the Southeast Asian Archive of the University of California, Irvine Libraries, has recently presented an exhibition called “Documenting the Overseas Vietnamese Experience” (URL: http://www.lib.uci.edu/new/seaexhibit/vietnamam.html). It is also worth noticing the efforts of an individual Vietnamese, Trong Minh, in his published series “Vẻ Vang Dân Việt = The Pride of The Vietnamese People”, which recorded case histories of success of numerous overseas Vietnamese.

USE OF INFORMATION

Personal Use

People seek information for their own use. The Vietnamese are no exception. The author of this paper is aware of only a few library users’ surveys done for Vietnamese materials in public libraries. However, personal use of this body of recorded information can be ascertained by at least the three following factors: 1) the continued growth of non-book music materials mentioned earlier; 2) the presence of Vietnamese language collections now available in almost all medium-sized and large North American cities; and, 3) the proliferation of newspapers, especially the ones distributed free at grocery stores. The third factor is a unique phenomenon of the overseas Vietnamese community. Sơn Tùng has observed: “Trong cộng đồng người Việt ở Mỹ hiện nay có hai nghề làm ăn thường được nghe nói tới nhiều nhất là nghề mở tiệm phở và ra báo.” (Right now, within the Vietnamese community in the U.S., the two most talked-about businesses are to open a “pho” (Vietnamese noodle soup) restaurant and to publish a newspaper).[21] The free newspapers overwhelmingly outnumber the ones that sell. According to Chữ Bá Anh, in February 1991, in the United States there were about 180 newspapers, among which only 10 were for sale.[22] In addition to literary matter such as shorts stories, “feuilleton” novels, and poetry, these newspapers also provide their readers with numerous advertisements for local businesses, as well as local, national and even international news. It can be assumed that the overseas Vietnamese, on an individual basis, have relied heavily on these publications–especially because they are free– to satisfy their own information needs, both educational and recreational. The author of this paper is not aware of any systematic and comprehensive study on why and how Vietnamese seek and use information. Through personal contacts, the author of this paper has acquired the following use statistics:

- from the Saskatchewan Provincial Library: in 1999, 186 requests were submitted for Vietnamese materials and 1311 Vietnamese titles were circulated to fill these requests (Information provided by Joseph Onufer, Saskatchewan Provincial Library, Multilingual Services).

- from University of California at Irvine (UCI): interlibrary loan requests average 25/quarter, 50-60% of these requests concern the Vietnamese (Information provided by Anne Frank, Librarian, Southeast Asian Archive, UCI).

- from Bibliothèque de Montréal: in 1999, external loans total 79,430 (78,863 for adults and 567 for children) (Information provided by Lâm Văn Bé, Head Librarian of Mile-End Branch Library, Responsible for Multilingual Collection Development, Montreal Public Library; See Appendix C).

- from Santa Ana Public Library: between July 1998 and June 1999, total Vietnamese items checked out 26,429; size of collection 5,822; total Vietnamese patrons 4568; average number of books checked out per person per year 5.78 (Information provided by Angie Nguyen, Newhope Branch Library Learning Center).

As a rule, these statistics should be used with caution for two reasons: 1) They reflect only the number of materials checked out through circulation systems; they do not include in-library uses of materials; 2) In many places, some cities in California for example, non-resident policy recently implemented, which imposes an annual fee for library cards for non-residents, has resulted in lower Vietnamese materials circulation figures.

Community Use

Vietnamese people always have a very strong feeling toward community life. Coming to the U.S. as refugees, sponsored by church groups or service clubs, they were first scattered across the country, but after a few years they were regrouped in large communities. This secondary migration, which is believed to continue,[23] has resulted in four large centers of overseas Vietnamese in the United States: California, Washington (State), Texas, and the District of Columbia (D.C.) area (D.C. + Maryland + Virginia). And wherever we have a sizeable Vietnamese community, we have a Vietnamese association as an umbrella organization representing the whole community with secondary organizations such as “mutual assistance associations” (MAA), high school alumni associations, Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces veteran organizations, and religious associations. A conservative estimate puts the current number of MAA in the United States at 1300.[24] Many of these organizations publish newsletters, bulletins or occasional papers. Mr. Nguyễn Hùng Cường’s A Bibliography of Overseas Vietnamese Periodicals and Newspapers, 1975-1995, although not exhaustive and only up to 1995, lists almost 200 titles under the two categories of Occasional Papers and Newsletters. These publications not only provide news that are specifically meaningful for the target groups but also give other useful information for the resettlement of their members. In Canada we even have an umbrella organization for the whole country: the Vietnamese Canadian Federation, which, in addition to their bimonthly Bulletin and quarterly Magazine, also issues proceedings of their annual summer seminars (each seminar focused on a specific topic; last year, the seminar was held on November 13-14, 1999, in Ottawa, and the topic was “Women as Agents of Change in the New Millennium”; proceedings of recent seminars are now available at the Federation’s website at: http://www.vietfederation.ca). Vietnamese business directories, compiled either by the local Vietnamese association or the local principal Vietnamese newspaper, are now available in most large North American cities. And, of course, all local associations have information or inquiry service to help fellow newcomers in their house searching, job seeking, and in their dealings with local health, social and educational agencies. Another characteristic of overseas Vietnamese community life is the special role played by religious centers like Buddhist temples and Roman Catholic churches. Within smaller communities, especially where an umbrella Vietnamese association does not exist, these centers are functioning like community centers. All kinds of information exchange occur at these locations on: funerals, weddings, special events (Lunar New Year, Mid-Autumn Festival, Vietnam Flood Relief Funding, etc.). Last, but not least, local heritage language schools (mostly operating during weekends) are also important consumers of recorded information such as textbooks, spelling books, children’s books, music materials, etc.

Institutional Use

Government and Non-Government Use

Government agencies at all levels– federal, state/provincial, and local– and non-government organizations (NGOs)–e.g., local churches and/or charities– are not only major information creators but also important information users. They need to have reliable data in their project/program/service planning, and in many instances, they seek and use information generated by advocacy groups or by the Vietnamese organizations themselves. In Canada, the Vietnamese Canadian Federation has come many times before various House of Commons committees to submit all kinds of information these committees needed. In the United States, IRAC (and later SEARAC) constantly gathered information–mostly demographic– about Vietnamese refugees/immigrants and provided them to government agencies when requested. Government agencies and NGOs, however, should be encouraged to also make use of non-Vietnamese materials, which tend to offer a more analytic overview of the Vietnamese experience, since the Vietnamese materials often are more personal but less analytical.[25]

Research

This is an important area of information use among overseas Vietnamese. After 25 years of resettlement overseas, a whole new generation of Vietnamese has grown up in the United States and elsewhere. They “enter the universities of the US with the highest grade scores and test averages, tend to enter the most difficult fields of study, and have the highest graduation rate of any ethnic group.” [26] Many of these younger Vietnamese Americans continue to study at the graduate level. They aggressively seek and selectively use information about the older generations’ struggle to adapt and survive in the new and alien environment. We are now witnessing the appearance of numerous studies in English on issues like acculturation, generation gap, identity crisis among Vietnamese Americans. In a recent study conducted at UC Berkeley by doctoral candidate Thai C. Hung, it was found that the younger generation of overseas Vietnamese, growing up in the United States, still studying in or graduating from American universities, are now returning to their roots, making more friends with other fellow Vietnamese Americans, participating more in Vietnamese community activities. [27] Đỗ Quý Linh Thư, a second-year student at Rice University, Houston, Texas, let us know how she used recorded information in the following statement: “Thanks to the miracle known as electronic mail, or e-mail, I have learned some pretty fascinating anecdotes. One e-mail I received mentioned a sociological report on Vietnamese Americans, stating that Vietnamese Americans performed extremely well in school because we, supposedly, have excellent memories and great big families that stress familial ties and interdependence.” [28] In addition to the traditional printed sources, of course, these researchers also make use of state-of-the-art information technology advances, such as the Internet, electronic journals, maillists, and usegroups. Their dual function as information consumers and information providers will definitely provide new dimensions for the body of recorded information on overseas Vietnamese experience.

CONCLUSION

The Vietnamese, as one of the newest ethnic groups in the United States, have achieved amazing successes in almost every aspect of American society. In the information domain, they have generated a significantly large body of recorded information. A Vietnamese literature in exile was blossoming during the late 1980s and continued to thrive up to today. The number of magazines and newspapers produced by the overseas Vietnamese, especially during the 1990s, was beyond imagination. This body of information has been put in good use by various Vietnamese organizations as well as government agencies and NGOs. The organization of this body of recorded information, however, although already started almost two decades ago, is still inadequate and makes research work in this field very difficult.

NOTES

- Paul James Rutledge. The Vietnamese Experience in America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992. 3.

- Statement of Charles Sykes, Head of the U.S. Delegation, to the Seventh CPA Steering Committee (available online at: http://www.usia.gov/regional/ea/vietnam/refuge96.htm).

- Mark E. Pfeifer. A Demographic and Socioeconomic Profile of the Vietnamese Community in Canada (available online at: http://ceris.metropolis.net/vl/community/pfeifer1.html).

- Angie Nguyen. Vietnamese in the United States (available online at: http://www.library.ca.gov/LDS/diversity/vietnamese.pdf).

- Almost all issues of this monographic series were authored by high-ranking South Vietnamese army officers. A search in the Library of Congress’ online catalog results in 20 entries for this series (18 by Vietnamese, one by a Cambodian, and one by a Laotian).

- Nguyễn Hùng Cường. Kiểm điểm 20 năm báo chí Việt Nam hải ngoại, 1975-1995 (Report on 20 Years of Overseas Vietnamese Newspapers, 1975-1995). [S.L. : The Author, 1996 ?]. 5.

- Nguyễn Hữu Nghĩa, “Sơ-kết 15 năm văn học VN lưu vong” (Preliminary Account of 15 Years of Vietnamese Literature in Exile), Van Xa 3 (July 1990): 8.

- Nguyen Hưng Quốc, “Hai mươi năm văn học Việt Nam ở hải ngoại” (Twenty Years of Overseas Vietnamese Literature), in Tuyển tập hai mươi năm văn học Việt Nam hải ngoại, 1975-1995 (Anthology of Twenty Years of Overseas Vietnamese Literature, 1975-1995), compiled under editorial direction by Trương Đình Nho, with the assistance of Cao Xuân Huy, Khành Trường, Trương Đình Luận. Glendale, Calif.: Đại Nam, 1995.

- Nguyễn Ngọc Bích, “Vị trí trung tâm của văn-học Việt-Nam hải-ngoại” (The Central Position of the Overseas Vietnamese Literature) in Nghiên cứu và nhận định (Research and Observations), 23. Washington, D.C.: Nghị Hội Toàn Quốc Người Việt Tai Hoa Ky (National Congress Of Vietnamese in America), 1987.

- Nguyễn Hùng Dũng, “Sách Việt ngữ phát hành tại hải ngoại trong năm 1986” (Vietnamese Books Published Overseas In 1986), Phụ Nữ Diễn Đàn Xuân (Special Issue for Lunar New Year) 1987: 77-81.

- Võ Phiến, “Bài [i.e. Vài] ghi nhận về văn học lưu vong” (Some Obversations on the Literature in Exile) in Nghiên cừu và nhận đinh (Research and Observations), 20. Washington, D.C. : Nghi Hoi Toan Quoc Nguoi Viet Tai Hoa Ky (National Congress of Vietnamese in America), 1987.

- Nguyễn Ngọc Bích. Tình hình văn học hải ngoại 1987 (Situation of Overseas Literature in 1987). Springfield, Va.: The Author, 1988 (photocopied typescript paper).

- ———————–, “Nhìn lại năm qua, Canh Ngọ, 1990: những hướng phát triển của văn học VN hải ngoại” (Flash back on last year, Year of the Horse, 1990: development trends of overseas Vietnamese literature), Ngày Nay 222 (Feb. 1 & 15, 1991): C1-C2, C8.

- ———————–, “Tính sổ cuối năm con mèo, đầu năm rồng: một cái nhìn về thơ văn Việt Nam trong năm cuối cùng của thế kỷ” (Account at end of Year of the Cat, beginning of Year of the Dragon: a look at Vietnamese literature of the last year of the century), Ngay Nay 427 (Jan. 15, 2000): C3.

- Nguyễn Hưng Quốc, op. cit.., 21.

- Võ Phiến, op. cit., 21.

- Nguyễn Hoàng Nam, “Tổng kết sinh họat sách báo và văn nghệ hải ngoại 1992” (General Account of Overseas Publishing and Literary Activities 1992), Song 128 (Jan. 1993): 115.

- Nguyễn Ngọc Bích, “Tính Sổ…”, op. cit.

- Chữ Bá Anh, “Sinh họat của báo chí và truyền hình Việt Nam tại Hoa Kỳ” (Vietnamese Media and Television Activities in the U.S.), Nguoi Viet (Feb. 16, 1991): A3

- Nguyễn Hùng Cường, “Tài liệu việt học tại các thư viện lớn và trung tâm Việt học” (Vietnamese Studies Documents at Large Libraries and Vietnamese Studies Centers) in Nghiên cứu và nhện định (Research and Observations), 48-56. Washington, D.C.: Nghị Hội Toàn Quốc Người Việt Tại Hoa Kỳ (National Congress of Vietnamese in America), 1987.

- Sơn Tùng, “Những ý nghĩ vụn về vấn đề báo biếu'” (Some ideas about the issue of free newspapers), Tiếng nói thủ đô 53 (June 29, 1991).

- Chữ Bá Anh, op. cit.

- Douglas Pike. Việt kiều in the United States: political and economic (Lubbock, Tex.: Texas Tech University, Vietnam Center, 1998), p. 10.

- —————, op.cit., p. 29.

- Yen Le Espiritu. Vietnamese in America: an annotated bibliography of materials in Los Angeles and Orange County libraries. (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center, Resource Development & Publications, 1988), p. iv.

- Douglas Pike, op. cit., p. 23.

- Nguyễn Tử Quý, “Ở trung học tôi muốn làm người Mỹ trắng, lên đại học và khi đi làm, tôi trở về nguồn Việt” (In high school I wanted to be like white Americans, entering university and in the workplace, I come back to my Vietnamese origin), Thoi Bao 593 (Jan. 13, 2000): 142-143.

- Đỗ Quý Linh Thư, “The Vietnamese American Family”, Người dân 113 (Jan. 2000): 27-29.

APPENDIX A

Selected Bibliography of Bibliographies

- Espiritu, Yen Le. Vietnamese in America: an annotated bibliography of materials in Los Angeles and Orange County libraries. Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center, Resource Development & Publications, 1988.

- Halpern, Joel Martin et al. A bibliography of Cambodian, Hmong, Lao, and Vietnamese Americans. Amherst, Mass.: University of Massachusetts, 1992.

- Hastie, Diane. Vietnam: une bibliographie de publications récentes = Vietnam: a bibliography of recent publications. Quebec City, Quebec : GERAC, Université Laval, 1992.

- Hoang, Trang et al. Emergence of the Vietnamese American Communities: a bibliography of works including selected annotated citations. Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center, 1996.

- Huỳnh Đình Tế. Vietnamese language materials sourcebook. Folsom, Calif.: Southeast Asia Community Resource Center, 1990.

- Lewis, Judy. Selected resources: people from Cambodia, Laos & Vietnam. Folsom, Calif.: Southeast Asia Community Resource Center, Folsom Cordova Unified School District, 1993.

- Marr, David G. and Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers. Oxford, England; Santa Barbara, Calif.: Clio Press, 1992.

- Nguyễn Đình Thám. Studies on Vietnamese language and literature: a preliminary bibliography. Ithaca, N.Y.: Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 1992.

- Nguyễn Hùng Cường. A bibliography of overseas Vietnamese periodicals and newspapers, 1975-1995 = Mục lục báo chí Việt Nam hải ngoại, 1975-1995. Washington, D.C.: Southeast Asia Resource Action Center, 1997.

- Pfeifer, Mark. Bibliography of Vietnamese-related research, 1958-1989 (Available online at: http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Stage/8421/).

- —————-. Bibliography of Vietnamese-related research, 1990-2000 (Available online at: http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Stage/8421/).

- Pham Henry Thuoc V. A bibliography of Vietnamese magazines, newspapers and newsletters published in the United States and other countries = Mục lục tạp chí, báo chí, thông tin xuất bản ở Hoa Kỳ và thế giới. Aurora, Colo.: Vietnamese-American Cultural Alliance of Colorado, 1988?

- Saskatchewan Education. Provincial Library. Vietnamese bibliography. Rev. ed. Regina, Sask. : Provincial Library, 1988.

- Schafer, John C. Vietnamese perspectives on the War in Vietnam: an annotated bibliography of works in English. New Haven, Conn.: Yale Center for International and Area Studies, 1997.

- Singleton, Carl. Vietnam studies: an annotated bibliography. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 1997.

- Texas Tech University. Vietnam Center. Vietnam Archive holdings as of April 1, 1999. Lubbock, Tex.: Texas Tech University, Vietnam Center, 1999.

- United States. Library of Congress. Vietnamese holdings in the Library of Congress: a bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1982.

- United States. Library of Congress. Vietnamese holdings in the Library of Congress: supplement, 1979-1985. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1987.

APPENDIX B

Selected List of Vietnam-Related Websites

General Information

eViet (The Vietnamese Internet Directory)

http://eviet.com/frame/welcome.html

Saigon.Com

http://www.saigon.com/saigon.html

VietGate

Vietnamese Boat People

VietPage

VietSpace

Viet-Net

VN-Central (Search Directory for Vietnamese Online)

Community

New Orleans Vietnamese

Vietnamese Canadian Federation

Vietnamese Association in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

http://www.freenet.edmonton.ab.ca/viets/

Vietnamese Association in British Columbia, Canada

http://www.geocities.com/Paris/Arc/7599/

Vietnamese Association of Michigan

http://www.hoinguoivietmi.com/

Vietnamese Community Council in Ottawa

http://www.vietfederation.ca/ottawa/index.htm

Vietnamese Community in Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Vietnamese Community in Washington, DC Metropolitan Area

http://www.freeviet.org/cdhmv/cdhmv.html

Vietnamese in Northeastern USA

Associations

LEAF-VN (The Library and Education Assistance Foundation for Vietnam)

UCLA Vietnamese Student Union

http://www.studentgroups.ucla.edu/vsu/

Vietnamese Association for Computing, Engineering Technology and Science

http://www.vacets.org/vacets.html

Vietnamese Cultural Society of Metropolitan Washington

Vietnamese Economics Network

http://www.arts.uwaterloo.ca/~vecon/index.html

Vietnamese National Military Academy Alumni Association

Vietnamese Mutual Assistance Association

http://hometown.aol.com/vmaatx/vmaa.html

Vietnamese Professionals Society

Vietnamese Student Associations Worlwide

http://www.geocities.com/CollegePark/2929/

Exhibition

Canadian Museum of Civilization

http://www.civilization.ca/membrs/traditio/vietnam/viint00e.html

Documenting the Vietnamese Refugee Experience

http://www.lib.uci.edu/new/seaexhibit/vietnamam.html

News Media

Ngày Nay (Houston, Texas, USA)

http://www.asianmediaguide.com/vietnam/pub/ngay_nay.html

Người Việt Daily News (Westminster, California, USA)

Thế Kỷ 21 (Garden Grove, California, USA)

Thời Báo (Toronto, Ontario, Canada)

http://www.thoibao.com/vietfpmw.htm

Về Nguồn

http://www.venguon.org/magazine/bao_intro.htm

Radio and Television Stations

Đài Tiếng Nói Việt Nam (Montreal, Quebec, Canada)

http://alcor.concordia.ca/~dm_doan/cungvang.htm

Radio Free Asia

Vietnamese Broadcasting Network

VietScape

VNCR (Garden Grove, California, USA)

Voice of Vietnam Radio

Research

Cornell University Library

http://www.library.cornell.edu/catalog

George Mason University

Harvard-Yenching Institute

http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~yenching/index.html

Institute of Vietnamese Studies

Library of Congress

http://lcweb.loc.gov/z3950/gateway.html#other

Southeast Asia Resource Action Center

Southern Illinois University Morris Library

Texas Tech University Vietnam Center

http://www.ttu.edu/~vietnam/vietnam.htm

Vietnamese Studies Internet Resource Center

http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Stage/8421/

UCI Libraries

University of Hawaii Libraries

http://www.hawaii.edu/library/

University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies

http://www.umich.edu/~iinet/csseas/

University of Washington Libraries

http://www.lib.washington.edu/

Yale University Library

APPENDIX C

| Bibliothèque de Montréal | ||||||

| Collection des livres vietnamiens : inventaire et prêts externes | ||||||

| 1999 | ||||||

| Bibliothèque | Inventaire | Prêts externes | ||||

| Adultes | Jeunes | Total | Adultes | Jeunes | Total | |

| Mile-End | 7 068 | 226 | 7 294 | 56 706 | 516 | 57 222 |

| Côte-des- Neiges | 3 543 | 25 | 3 588 | 19 770 | 46 | 19 816 |

| Plateau Mont-Royal | 718 | 0 | 718 | 2 387 | 5 | 2 392 |

| Total | 11 329 | 251 | 11 580 | 78 863 | 567 | 79 430 |

| Van Be Lam | ||||||

| Bibliothécaire Responsable | ||||||

| Bibliothèque Mile-End | ||||||

| Chargé du développement des collections des langues d’origine | ||||||

| Bibliothèque de Montréal | ||||||

(This paper presented at the Conference on Overseas Vietnamese Experience, Texas Tech University, Vietnam Center, Lubbock, Texas, USA, Mar.31 – Apr. 1, 2000)

You may like

Reflections on New Era of National Rise by Vietnam General Secretary Tô Lâm

Of Space & Place: On the Nationalism(s) of Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s “Our Ghosts Live in the Future”

Postwar Music In Vietnam And The Diaspora

Translation: The Decision in 2013 of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Certain Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform

Thủ Đức Demonstration High School: A Modern Educational Policy and Teaching Method of the Republic of Vietnam

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years agoRethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

-

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years agoDeporting Vietnamese Refugees: Politics and Policy from Bush to Biden (Part 1)