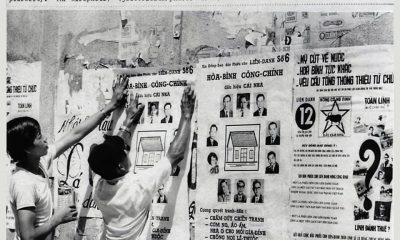

During the COVID-19 pandemic, on April 30, 2020, the 45th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, many Vietnamese Americans woke up in the early hours to prep traditional foods to feed the hungry. (Source: “A tsunami of kindness”)

Y Thien Nguyen

Summary

This study is aimed at examining the impacts and response strategies to the COVID-19 pandemic among Vietnamese American communities in Orange County, southern California. These communities pose an intriguing puzzle for researchers to solve: preliminary city-level data of Southern California as of May 18 suggest that they have been much more successful than others in limiting the infection. The three cities in Orange County (Westminster, Garden Grove and Fountain Valley) with the largest concentrations of Vietnamese-Americans had twice or three times lower numbers of cases as a percentage of the population, compared to five cities around them in Orange County with few Vietnamese-Americans (California Department of Public Health 2020; Los Angeles Times Staff 2020). The city of Westminster with the highest concentration of Vietnamese-Americans (40% of the total population) also had the lowest ratio of cases (75 cases or 0.08% of the population).

While data remain sketchy at this point, the pattern is quite striking and demands an explanation. How and why are Vietnamese different from most other groups of immigrants and people of color, who have disproportionately bore the brunt of the pandemic? Guided by this puzzle, our study hopes to contribute to a growing scholarly literature about the impacts of socio-cultural factors on the different ways different communities respond to diseases and disasters. As California is reopening, we plan to employ a mixture of online tools as well as field research in Orange County if conditions permit. We aim to develop innovative protocols for conducting research online and under conditions of physical distancing. Beyond academia, our data and findings will most directly help local governments where Vietnamese-American communities are located to plan for improved services if the pandemic returns. More broadly, we hope our case study of the pandemic as a social phenomenon will inform scholars, policymakers, practitioners, and community leaders across the globe as all of us reflect on the impacts of the first wave and prepare for future waves of this pandemic.

Designed as a rapid-response project with research conducted during Fall 2020, this study will be the first phase of a larger collaborative project led by Y Thien Nguyen, a Research Fellow in the US-Vietnam Research Center at the University of Oregon. The larger project’s goal is to study over an extended timeframe the unique vulnerabilities and resilience of Vietnamese-American communities there as they recover yet remain on the alert against likely future waves.

Background

Southern California- particularly Orange County- is home to the highest proportion of Vietnamese people outside of Vietnam (United States Bureau of the Census 2019). Largely considered the “capital of Vietnamese America” (Võ 2008:85), Orange County’s “Little Saigon” is a thriving enclave of Vietnamese American culture, politics, and entrepreneurship that developed after Vietnamese refugees arrived in the U.S. following the end of Vietnam’s civil war in 1975. Since then, subsequent waves of Vietnamese refugees, immigrants, and their children have come to call Little Saigon and surrounding areas home. While the COVID-19 pandemic has enveloped all areas of social life for a range of racial/ethnic groups across the country and the world, preliminary analysis of city-level data shows a clear pattern of much more limited pandemic spread where Vietnamese Americans reside. We hope to identify and analyze the dynamics involved in this case not only to make scholarly contributions but also to promote the welfare of our community.

Scholarly Contributions

Research on diseases and disasters has long noted their greater negative impacts on people of color and immigrants in the U.S., who tend to be poorer, less educated, and less cushioned by social networks and safety nets. Among these groups, Vietnamese Americans fit the profile of those vulnerable to disasters in general and to this COVID-19 pandemic specifically. First, they are more likely to live in multigenerational family households relative to other Asian Americans and non-Hispanic whites (Pew Research Center 2015), which is a risk associated with contracting COVID-19. There is also evidence that lack of insurance, economic constraints, poor mental health supports, and language barriers to health information lead to poor health access and outcomes for Vietnamese Americans relative to the general population (D’Avanzo 1992; Do et al. 2014; Leong et al 2001; Ngo-Metzger et al. 2003). In addition, Vietnamese Americans are highly represented in the nail salon and restaurant industries, which have been some of the hardest hit industries after the initial wave of the pandemic. Overrepresentation in these fields may also present disproportionate health risk to employees as the California economy begins to re-open. Rising reports of anti-Asian sentiment and racism may also render Vietnamese Americans more vulnerable in this pandemic context.

Nevertheless, there is some evidence that Vietnamese Americans have been more resilient than other racial-ethnic groups in their disaster recovery trajectories. Using Hurricane Katrina aftermath as a case study, VanLandingham (2017) argues that Vietnamese Americans in New Orleans demonstrated unique forms of group solidarity and resilience in the face of economic and natural disaster that helped them recover more quickly than other groups. VanLandingham suggests that Vietnamese Americans have particularly strong group solidarity because of shared common values, narrative, and frames including, 1) an antipathy toward the current regime in Vietnam 2) an explicit element of anticommunism, 3) an implicit element of support for capitalism 4) a melancholy about estrangement from their homeland and alienating features of American society. In the same vein, previous studies on Vietnamese American communities, attitudes, and behaviors highlight how co-ethnic Vietnamese Americans help each other in ways that are exclusive to outsiders by utilizing social capital resources, informal information, and institutional bases for collective community and political action (Lee and Zhou 2015; Võ 2008).

There are obvious contextual differences between our study and VanLandingham’s work because 1) COVID-19 is a wide-reaching pandemic and global public health crisis, not a natural disaster with regionally concentrated effects, and 2) Vietnamese Americans in Orange County are, on average, more affluent than those in New Orleans at the time of Katrina, and the Vietnamese American population in Orange County in 2018 was 19 times larger than the Vietnamese population in Orleans Parish as of the year 2000 (Aguilar-San Juan 2009; American Community Survey 2018; United States Bureau of the Census 2000 via Social Explorer).

Yet, it’s worth asking how well VanLandingham’s findings explain our preliminary observation about the limited spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in Vietnamese American communities in Orange County? How might Vietnamese Americans’ shared values, narratives and frames explain their apparently lower level of vulnerability to COVID-19? To what extent have those factors operated differently from other disasters? If such factors did have positive impacts in the last wave of the outbreaks, how might they help these communities prepare for future waves?

By focusing on the socio-cultural strengths and vulnerabilities of Vietnamese American communities, we hope to contribute to theoretical debates in sociology and political science about the roles of socio-cultural frames, narratives, and institutions not only in how communities cope with disasters or pandemics but also in how they respond to challenges in other spheres such as political exclusion, racial discrimination, and economic blight. We also expect our research to give us the opportunity to reflect broadly on such issues as public trust, information sharing, ethnic inequality, and cultural biases that are often sharply revealed during social crises.

Work Cited

Aguilar-San Juan, Karin. 2009. Little Saigons: Staying Vietnamese in America. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

California Department of Public Health, “California Covid-19 Hospital Data and Case Statistics.” Retrieved May 18th, 2020

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. “COVID-19 and Racial-Ethnic Minority Groups.” Retrieved May 8th, 2020

D’Avanzo, Carolyn E. 1992. “Barriers to Health Care for Vietnamese refugees.” Journal of Professional Nursing 8(4): 245–53

Do, Mai et al. 2014. “Perceptions of Mental Illness and Related Stigma among Vietnamese Populations: Findings from a Mixed Method Study.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 16(6): 1294–98

Lee, Jennifer and Min Zhou. 2015. The Asian American Achievement Paradox. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation

Leong, Frederick, and Anna Lau. 2001. “Barriers to Providing Effective Mental Health Services to Asian Americans.” Mental Health Services Research 3(4): 201–14

Los Angeles Times Staff, “Tracking Coronavirus in California.” Retrieved May 18th, 2020

Ngo-Metzger, Q., et al. 2003. “Linguistic and Cultural Barriers to Care: Perspectives of Chinese and Vietnamese Immigrants.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 18(1): 44–52

Pew Research Center. 2017. “Vietnamese in the U.S. Fact Sheet.” Retrieved May 12th, 2020

United States Map. In: SocialExplorer.com. ACS 2018 (5-Year Estimates; Asian Category: Total Vietnamese). Retrieved May 14th, 2020

U.S. Census Bureau. 2019. “American Community Survey.” Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office

VanLandingham, Mark. 2017. Weathering Katrina: Culture and Recovery among Vietnamese Americans. New York, NY: Russel Sage Foundation

Trinh Võ, Linda. 2008. “Constructing a Vietnamese American Community: Economic and Political Transformation in Little Saigon.” Amerasia Journal, 34(3), 84-109

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago