ARCHIVES

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)

Published on

By

Tạ Văn Tài

Tai Van Ta, Harvard Law School

May 2007

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5)

ABSTRACT

Prefacing and ending with brief summaries of the political history of South Vietnam (1954-75), this paper focuses on the 1970 Senatorial elections, studied through a pre-election poll and an exit poll of 875 voters in the capital city of Saigon (probably the only political poll, during that period, conducted independently by a non-governmental group of researchers under the guidance of a professor of social science research methods). The analysis of the results of the polls show that (1) Even the population sample is not idealistically a stratified random sample of the whole nationwide population, the study can predict correctly the outcome with the three victorious slates of candidates, although with a slight difference in ranking.; (2) that the mass followings of the two dominant religious forces, the Catholics and the Buddhists, and their prominent personalities, were the factors in their slates’ respective victories, with the ‘third force’ Buddhists being the strongest political force in society and the number one victor in the elections, even they were anti-government and ran against a government-supported slate of candidates; this latter, even with the full force of government help, came second to the Buddhist slate, and the interviewed voters said they voted for the Buddhist slate because besides its religious (Buddhist) representativeness , the voters wanted peace represented by the Buddhists’ position; and that (3) the Buddhists were victorious despite the fact that they did not use so much the campaign means (interviews in the press, posters and banderoles) as the other slates, and despite that they were heavily criticized in many articles in the newspapers, but they fiercely condemned the government.

It is interesting to note that this free and fair election, encouraged by US Ambassador Bunker, was the climactic development of democracy in South Vietnam, which incipient democracy, unfortunately, was to be killed—even before the Communist troops overran South Vietnam in 1975–by President Nguyen Van Thieu just one year later, in 1971, when he ran a one-man show of presidential elections.

SECTION IV. WHAT WAYS AND MEANS FOR CAMPAIGNING DID THE CANDIDATES USE FOR REACHING THE VOTERS?

There were people who would not know how to answer this question, mainly among those who said they would not go to the polling booth, they did not vote for anybody or just said “only decide when in the voting booth” or” just pick up at random some votes and cast them”. These people did not know the means used by the candidates for campaigning because they did not even read newspaper.

However, there are a number of means for campaigning in that 1970 Senatorial election, not unlike those used in the American political campaigns, which we summarize in Table 9.

Table 9. Ways and Means of campaigning

In order from most used to least used, we list, in the following columns, the ways and means of campaigning which the voters mentioned that they had the experience of being exposed to: (1) the press, (2) posters and banderoles, (3) radio and television, (4) rumor and organized propaganda, (5) influence through persons, (6) infusing fixed idea, (7) relying on personal sympathy, and (8) by all available ways and means.

The SLATES OF WAYS AND MEANS THEY USED TO REACH VOTERS

CANDIDATES : (1) : (2) : (3) : (4): (5) : (6) : (7) : (8) :

- N V Huyen : 216 : 150 : 108 : 37 : 33 : 34 : 6 : 11 :

- V V Mau : 152 : 135 : 85 : 67 : 32 : 34 : 16 : 11 :

- H V Cao : 66 : 59 : 33 : 25 : 11 : 12 : 3 : 4 :

- N C Hach : 45 : 50 : 52 : 17 : 9 : 6 : 15 : 1 :

- N P Dai : 31 : 43 : 56 : 14 : 8 : 4 : 4 : 0 :

- N N Huy : 25 : 22 : 25 : 9 : 10 : 5 : 7 : 8 :

- T V Le : 27 : 29 : 30 : 13 : 10 : 2 : 1 : 1 :

- T C Cuu : 19 : 28 : 25 : 12 : 3 : 6 : 0 : 3 :

- N H To : 18 : 27 : 30 : 5 : 4 : 6 : 0 : 1 :

10.N D Bang : 23 : 23 : 13 : 12 : 5 : 1 : 0 : 3 :

11.N A Tuan : 14 : 22 : 28 : 3 : 4 : 4 : 0 : 2 :

12.N G Hien : 23 : 20 : 11 : 7 : 7 : 4 : 1 : 1 :

13.N T Hy : 19 : 12 : 17 : 7 : 2 : 2 : 0 : 0 :

14.P B Cam : 5 : 10 : 10 : 8 : 3 : 2 : 0 : 1 :

15.N V Canh : 2 : 6 : 7 : 0 : 0 : 1 : 0 : 2 :

16. N V Lai : 4 : 9 : 6 : 1 : 3 : 2 : 0 : 0 :

TOTAL :689 : 655 : 636 : 237 : 144 : 125: 53 : 49 :

Our overall observation on the ways and means to reach the voters is: in a society much poorer than the United States for extensive use of expensive mass media, such as radio and television, or much poorer than the American politicians to organize large face-to-face meetings with the electorate, the Vietnamese candidates had tried to use the three most important mass media for them to reach the voters: the press, posters and banderoles, and radio and television, in vigorous and energetic way, as in the United States . For the leading slates ,a lot of voters mentioned these three means of mass media communication : N V Huyen 216,150,108 times; V V Mau, 152, 135, 85 times; H V Cao, 66,59,33 times. The remaining five means of reaching the electorate were mentioned by the voters only occasionally.

A. The press

Mentioned 689 times, the press was the predominant means for the candidates to reach the voters. Our sample in Saigon showed that for the 3 leading slates of candidates, the press was twice important than radio and television, even in an urban area where many families had radio and television sets and there were widespread distribution of posters and banderoles. Outside the urban areas, where fewer posters could be found due to the large territory to cover, and where radio and television sets were not everywhere, the press would be much more important.

The press introduced the candidates to the voters who would otherwise knew nothing about them: this was evident from the answers of some voters that they knew the candidates through the interviews of the slates published in Chinh Luan Newspaper, or other newspapers and magazines.. But perhaps more

importantly in terms of effect, the role of the press was mainly to reinforce the meager knowledge of the voters about the candidates and reminding them of the record, ability and moral quality of the candidates, without those personal qualities, the press would not be able to create instantly winnable candidates: most interviewees were obsessed with the personal prestige or qualities of a few candidates in a slate, for example, thanks to the newspapers, they remembered former Prime Minister T V Huong in the Bong Hue (Lily) slate as an incorruptible man, NV Huyen , head of that slate as a lawyer of rectitude, and Professor V V Mau , head of the Lotus slate, as a courageous minister of President Diem who shaved his head to protest president Diem in 1963. In other words, the press could not, in a short time, create vote-getting politicians , but would mainly remind the electorate of the intrinsic qualities of the candidates which had been built up over the years.. V V Mau’s slate refused to be interviewed by Chinh Luan newspaper but still became victor; on the other hand, the controversy caused by this slate of peace—heavily criticized by many articles in the press, and counterattacking fiercely—helped elect it (One interviewee said : “I voted for this slate because the members fiercely condemned the government” –“chui du qua”).

The scarce press reports on the slates of the political parties—N V Canh (2 mentions),P.B. Cam(5 mentions)—was due either to the low prestige of the parties or their meager financial resources to mobilize the press. Only the Cap Tien slate partially escaped this fate

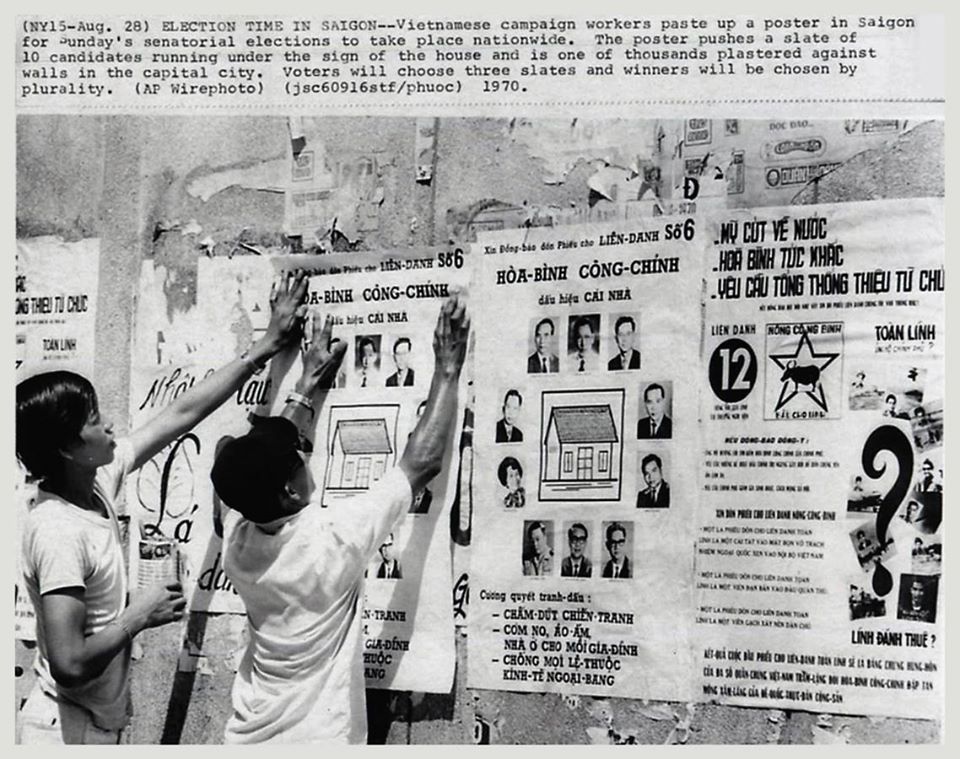

B. Posters and banderoles

Second to the press, these means of exposure to the voting public were equal for all slates, in terms

of size, quantity, time of posting. They should have had equal impact for all slates., but the voters many times mentioned these means in connection with N V Huyen and V V Mau slates (150 and 135 times), although we saw very few of their posters and banderoles in Saigon, but these means still reminded the voters about them and helped them, while they hardly remembered the posters and banderoles of other slates (from H V Cao slate down, only 59 times and less—especially P B Cam, 10 times, N V Canh, 6) . Some of these slates posted many more posters and hang many more banderoles than Huyen and Mau : N D Bang, T V Le, N P Dai, N A Tuan (rumors said that some spent more money than allowed to print more posters). Again the personal prestige of the candidates counted a lot and the fixed ideas of the voters about their merit made the voters remember the posters and banderoles, no matter what quantity of them was used.. Psychologically, that was understandable, because the empty mottoes such as “freedom, food and clothes, welfare” and even “peace” similarly used by many slates in their posters and leaflets would compare badly with the difficult real life situation of the people and make them insensitive to the means of campaigning to a great extent.. Again, the personal qualities of the candidates and the fixed ideas bout them in the mind of the voters who were already impressed by them prior to the campaign—all built up in long years before the balloting– were more decisive factors.

C. Radio and television

They were third in importance and the number of times they were mentioned (636) was more than all the rest of the ways and means listed in columns 3 to 8 (608), such as rumor and black propaganda, infusing of fixed ideas and personal sympathy. This fact allows us to predict that as Vietnam develops more access to television and radio for the rural people, these means would become important means for political mobilization and campaigning, as in the United States and other advanced countries.

Going a little into the substance of the radio and television messages, we see that the personality image projected by the candidates and their art of performance (eloquence, competence, confidence, etc..) had a great impact on the choice of the voters. Besides the exceptions of the N V Huyen and V V Mau slates which relied on religion and personal prestige of the head—and other members– of the slates and thereby succeeded in using radio and television to refresh the memory of the voters, the elegance, sweetness, and eloquence of the lady attorney N P Dai gave her slate the most mentions by the voters compared to the remaining slates. Next came professor N C Hach with 52 mentions, who, however, was subject to ridicule by the press because he sat at a separate table with his stern professor’s face while the other members stood up; the derision might have harmed him a lot. H V Cao was mentioned less in terms of radio and television performance but became the second highest vote getter nationwide, probably with help of the government. The N H To slate (motto: “peasants, workers, soldiers vote for soldiers”) had no personal prestige but built up its image of young men in wartime and attracted the votes of military men. Also belonging to the slates with skill in theatrical performance was N A Tuan which introduced lively its members.

D. Other means, less important: rumor and propaganda, influence through others, fixed idea, personal sympathy and “all means”

–First, campaigning effort with open propaganda, or rumor-mongering, by the candidates or by supporters such as clergymen in churches and Buddhist temples, political party leaders in official or semi-official meetings. V V Mau led the pack with 67 mentions, compared with NV Huyen, with 37, and H V Cao, with 25. With the anti-government stand and the determination of the Buddhists to gain victory in the first trial at political engagement, the V V Mau slate used effectively the mass propaganda and rumor among followers.

— Second, the use of the influence of other people. It applied mainly to women voters. Even the hardship of a wartime economy necessitated women’s prominent role in economic activities, they still did not pay much attention to politics. Men still dominated in politics, and political opinion, and therefore their choices (especially those of the husbands and the eldest sons) influenced the votes of the women in their families.

— Third, the fixed ideas about slates of candidates were due to the voters’subjective identification with their party/group or religion. That was one reason for the influence of religion and party/group.

–Fourth, also subjective, the voters’ sympathy with certain members in a slate. Professors Hach (15 mentions) and Huy (7 mentions) ranked above attorney Huyen by far (only 6 mentions) and only ranked below Professor V V Mau (16 mentions). The ranking of the three professors must be attributed to respect for the three well-known professors in the capital city of Saigon. Mrs. N P Dai gained a lot of female votes, because of her personal performance.

–Finally, the knowledge about a slate could be through “all means” over the years, including the press, radio and television, and group discussions combined. This lumping together of all means of exposure was mentioned by the voters in connection with the slates of V V Mau, N V Huyen and N N Huy (who just formed the Cap Tien Movement with many political activities)

PART III. CONCLUSIONS.

We have two groups of conclusions: on the relative success of the first (and probably the only) political poll and on the free and fair election in this incipient democracy in South Vietnam

A. Lessons drawn from this first and relatively successful political poll in South Vietnam.

Even the sample of 875 people in two districts of Saigon was not representative of the nationwide population or even the population of the capital city of South Vietnam at that time, this survey succeeded in predicting the three victorious slates of candidates: Huyen, Mau, and Cao, although the order of ranking was a little different than the final actual result, due to the sample being not random stratified sample because of lack of funding and time and accurate census data. This relative good result should be satisfactory enough if we know that the comparison of poll data among 16 slates of candidates was much more difficult than predicting the relative ranking of only two major parties contending in an election as in the United States.

The prediction was possible because there was no indication of actual fraud and litigation in this election on the loss of ballot boxes, or stuffing the boxes, even though there were complaints about not enough ballots in some voting sites, or government adding voting sites to make it difficult for slates to have enough campaign workers to supervise them (this might not be a problem for the Buddhists and the Catholics who had enough followers to cover them). The result reflected the relative strength of various political forces in South Vietnam at that time: the strongest being the Buddhist masses ( supporting the number one victor, nationwide: V V Mau slate), then the government supporters such as the military, the police and the administrative personnel (which made H V Cao slate came second) and then the Catholics (for whose support, N V Huyen came third); as for the political parties, they are second in strength, including the experienced ones such as the Dai Viet , which supported N V Canh and the Tan Dai Viet or Cap Tien , which launched the N N Huy slate.

Other findings of this poll that can be of value to the understanding of the behavior of Vietnamese voters: the grounds for their choice of candidates, the impact of their social background on voting, and the various ways and means for candidates for reaching them.

B. On the free and fair Senatorial election of 1970 in South Vietnam and lessons derived from it.

There is no dispute that the 1970 Senatorial election was a free and fair election, with the encouragement of the Americans.

Dr. Douglas Pike wrote in his Introduction to the book Bunker’s Papers that all this democratic development with the encouragement of US Ambassador Bunker came to naught after South Vietnam fell to the Communists in 1975. But the disintegration of the nascent democracy in South Vietnam started earlier in 1971 when President Nguyen Van Thieu, with the machination of his supporters, tried to assure his victory in the 1971 presidential election to the extent that only he remained as the sole candidate. Thieu first used technical reasons to eliminate the candidacy of his Vice president and rival Nguyen Cao Ky (alleging that he Ky did not have enough signatures of supporters) in order not to split the pro-government votes when he had to face General Duong Van (Big)Minh, who had the support of the Buddhist masses and Buddhist leaders of the Lotus slate in the Senate. But then General Minh withdrew his candidacy when he knew that facing Thieu without the splitting of the pro-government votes, especially with the machinations of the elections, would not be very promising. Thieu was the sole candidate for the presidency and thus he made the incipient South Vietnamese democratic regime become a one-man show. The man, who thus de-legitimized the democratic character of the regime and further lost popular support with the popular movement of denunciation of corruption in his government, later just counted on President Nixon’s promise of forceful retaliation with B52 bombings in case of North Vietnam’s military advance. Thieu was not being politically wise enough to know that the US, with Congressional War Powers Resolution that bound the hand of the US President, only gave South Vietnam a few years of “decent interval” for Vietnamization of the war and internal political strengthening to reach a negotiated peaceful solution with North Vietnam . With President Thieu’s continued resistance to a political solution (his “4 nos” policy—no negotiation with the Communist North and National Liberation Front in accordance with the Paris Cease-Fire Agreement etc..) while he no longer had any popular base of support, North Vietnam’s Political Bureau, under Le Duan, detecting the political weakness of Thieu regime, and aware through Kissinger’s assurance in 1971 to Brezhnev of the Soviet Union and Chou En-lai of China that the US would not return to South Vietnam and will “let the political process start” (“We are prepared to let the real balance of forces in Vietnam determine the future of Vietnam”, “if local forces develop again, we are not likely to again come 10,000 miles”, he said in recently declassified documents, NY Times Dec.24,2006, Associated Press March 1, 2002), decided to launch an all-out attack.. When the unilateral, secret promise of President Nixon for forceful retaliation against Communist attack did not come under President Ford when Nixon already resigned, Thieu blamed the Americans on national television and resigned and resigned to the necessity of looking for democratic popular support by ceding the Presidency to Tran Van Huong who then turned over the presidency and vice-presidency to General Duong Van Minh and Senator Nguyen Van Huyen with the new cabinet headed by Prime Minister Vu Van Mau of the Lotus slate, with the hope that the democratic leaders who were for peace would be acceptable to North Vietnam in negotiation for a cease-fire. But by then, this belated and desperate search for democratic legitimacy did not stop the advancing Communist troops, because the Politburo in the North had already decided on an all-out victory. The South Vietnamese forces no longer fought, except for a few units, and the Duong Van Minh government surrendered to the advancing North Vietnamese. Before North Vietnam decided to launch an all-out attack, if NV Thieu did not kill the incipient democracy in South Vietnam by running a one-man show and ignoring the opposition forces in the legislature, and accept the “Third Force” into the government, a peaceful solution negotiated with North Vietnam with the help of the Buddhist “Third Force” in the government of South Vietnam could have, in retrospect, create a chance for a viable coalition government leading to the peaceful reunification of the country, because in reviewing the history on March 31, 2005, former Prime Minister Vo Van Kiet (in Tuan Bao Quoc Te and Tuoi Tre papers) wished that the two former opposing sides during the Vietnam War could return to each other’s side (tro ve ben nhau) to join in the reconstruction of the country and he said “ it is time to recognize the great contribution of Vietnamese patriots living inside the former regime… and one must think of the role of Duong Van Minh cabinet and the political opposition forces of the Thieu regime.”

Did Ambassador Bunker’s well-meaning acts of encouragement of Vietnamese democracy really came to naught? I do not think so. Fast forward to the current situation in 2007 unified Socialist Republic of Vietnam. The elections in the last 35 years, prior to 2007, of the National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam did not allow the competition of alternative leaders running from outside the groups of candidates introduced by the Communist Party through the mechanism of Mat Tran To Quoc (Patriotic Front). Also, the number of candidates only exceeded the number of positions to be elected in each electoral district by one or two, meaning the people had to accept the 3 or 4 or 5 candidates introduced by the Party and could only eliminate one or two extra candidates present in the voting only for show purposes. However, Socialist Vietnam has changed the wording of article 4 of the previous Constitution, which claimed the Party to be “the sole leading force” in the country, to the current wording of claiming that the Party is “a leading force “ of the country; as well as adopted the national motto of striving for “ wealthy people, strong country, just, democratic and civilized society”. Also, the current process of preparation for the election in May 2007 of the 12th National Assembly permits the self-introduction of independent candidates. The regime’s policy, as per the Instructions of the Politburo and the Standing Committee of the National Assembly, also specifies the criteria for free and fair elections: that for each electoral district, the number of candidates to be introduced must at least double the number of positions to be elected, in an effort to change from the past practice of introducing only one or two extra candidates for each electoral district, and that at local voters’ assemblies to nominate candidates, the reasons for rejections of those not chosen for nomination should be immediately made transparent, and that during the campaign, even the Party Secretary-General competing with a village teacher should be treated equally in the electoral district, and that whatever result of voting would be accepted, no matter who wins, without distinction as to “blue candidate or red candidate” (“quan xanh, quan do”) (VietnamNet.vn March 17, 2007). Of course, genuine free and fair elections and democracy would exist only if the nomination process, as well as the campaigning, are not going to be sabotaged by local party cadre, as happened in the past when capable but non-party candidates were obstructed by all machinations from running (Ex: the case of the patriotic Professor. Nguyen Thien Tong, Ph.D. from Australia who remained in Saigon in 1975 to serve, who, after getting an MPP at Harvard, also contributed to the Fulbright program of Harvard in Vietnam for economic development, but who was still rejected twice when offering his candidacy in Saigon). This above-described new trend toward more democracy, even a still-to-be-tested democracy, is the outcome of Vietnam’s long process of Doi Moi (Renovation) since 1986, in all areas of life, from permitting the people to improve their life in a market-oriented economy to more advance toward the rule of law, to more and more respectful of human rights (more needed to be done), to opening up to the outside world with diplomatic and trade relations with many countries and especially with the United States. After lifting the long embargo and normalization of relations, the United States has provided legal assistance through the STAR program of USAID to improve the rule of law in Vietnam, by helping Vietnam conform Vietnamese law to the obligations of international standards; it has encouraged Vietnam in human rights performance through regular dialogue in bilateral contacts, and an agreement on freedom of religion; and although not having suggested any multiparty democracy (because that form of multiparty democracy is not specified in any international human rights document, so that socialist/communist countries can adhere to them, provided that they comply with the requirement of free and fair periodical elections with secret ballots), the United States has encouraged Vietnam to allow dissenters to freely express an opinion on political reform. Ambassador Bunker has posthumously vindicated the well-meaning intention of the United States for promoting democracy and development in Vietnam, which, at this time in the 21st century, is being carried out only by means of the power of persuasion, and not coercion, as Ambassador Bunker always advocated.

However, the goodwill gestures and the persuasion of the United States, as well as the pressure of rules of transparency and fair dealing due to Vietnam’s opening to the outside world (such as admission to the World Trade Organization), may have some impact on the economic, social and civil rights of the Vietnamese people, but still, they may have only limited impact on Vietnam’s democratization for more political, especially electoral, rights of the people. Despite the above-mentioned instructions on free elections from the Politburo and National Assembly Standing Committee, and the many suggestions (even of some retired Party leaders such as Mr. Vo Van Kiet) for more freedom for citizens, even non-party members, to put up their candidacy for National Assembly, the list of 1322 candidates for the National Assembly elections in May 2007 has been reduced to only 880 (of which, only 30 are self-nominated candidates), not even twice the number of 500 seats in the Assembly, because through 3 “rounds of negotiation”, the Party wanted to reduce the number of candidates, and thus, to guide the voters, in each electoral district, to a few candidates so that the voters can easily choose among them the ones that the Party wants to be elected, by simply “crossing out the name(s) to be eliminated in each electoral district” [the easy choice of “ 3 bỏ 2” or the choice of “see 3 names, vote for 2”] as Mr. Le Kien Thanh, the son of the late Party General Secretary Le Duan, himself described the tactics.

* The author of this study thanks his students M.T.Cuong, N.V.Chinh, N.H.Duc, V.T.Dat, C.D.Phuc V.Tan, N.V.Tung, N.X.Thang, N.V.Trung, N.V.Vinh, N.H.Y, who helped to interview the voters, and his colleagues’ professors Diep Xuan Tan and Le Cong Truyen for analyzing part of the data, and especially professor Nguyen Van Bong, Chairman of the Association for Administrative Research who had encouraged and financed this project.

The author dedicates this study to the memory of the two leaders in the victorious Hoa Sen (Lotus) Slate of Candidates in the 1970 Senatorial Elections: The head of the slate, Professor Vu Van Mau, former Saigon Law School Dean and professor of the author, and later the author’s colleague in the same school, and Dr. Bui Tuong Huan, Saigon Law School professor and President of Hue University.

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5)

You may like

Reflections on New Era of National Rise by Vietnam General Secretary Tô Lâm

Of Space & Place: On the Nationalism(s) of Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s “Our Ghosts Live in the Future”

Postwar Music In Vietnam And The Diaspora

Translation: The Decision in 2013 of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Certain Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform

Thủ Đức Demonstration High School: A Modern Educational Policy and Teaching Method of the Republic of Vietnam

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years agoRethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

-

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years agoDeporting Vietnamese Refugees: Politics and Policy from Bush to Biden (Part 1)