Download pdf

Abstract

This essay explores the evolution of Vietnam’s legal thought during the transformative years of the mid-20th century, focusing on the ideological divide between communism and republicanism. It examines how early visions of a modern legal framework influenced the country’s political trajectory and contributed to the current “socialist rule of law” in Vietnam. By analyzing the republican legal ideals embodied in Decree 13 (1946) and the 1946 Constitution—emphasizing judicial independence and justice protection—the essay highlights an alternative legal vision that briefly flourished before being overshadowed by the communist model post-1948. It argues that the shift from a republican legal spirit to a communist framework between 1945 and 1954 played a crucial role in Vietnam’s intense political and social upheavals. This study also challenges the dominant “grand narrative” of the inevitable socialist revolution, revealing overlooked ideological debates and the fragmented nature of Vietnam’s legal and political history.

Keywords: Vietnam, legal thought, Republicanism

Editor’s Note: The following is one installment of a five-part essay series by Nguyen Luong Hai Khoi, which details the history of legal thought in Vietnam from 1945 onward. This series was originally posted on our Vietnamese language site in 2019 and has been translated here by our English editor Vinh Pham.

Perhaps many people today do not know that in Viet Bac, at the end of the 1940s, within the inner circle of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam government, there was a debate about the choice between two paths – the republican regime or communism for the legal system of Vietnam.

A History of Legal Thought 1945 – 1956

Part 1: Republican Spirit 1946

Part 2: The February 1948 Letter – Law Must “Unite” with Administration

Part 3: The Attack of the Communists

Part 4: Responding to the Ideal of “Independent Judiciary,”

Part 5: Ho Chi Minh’s Legal System after the 1948 Debate

Studying how the communists and republicans of the first half of the 20th century envisioned a modern legal system for Vietnam will help us understand the origins of the political choices made by various social forces in Vietnam during the 20th century, and comprehend the essence of the current “socialist rule of law” situation in Vietnam today.

Fragments of a “The Grand Narrative”

For over seven decades in Vietnam, there has been a storytelling approach that is deemed an unchangeable “truth”: the “socialist revolution” (or the path of communism) is an “inevitable historical choice.” Since the 1990s, even after the Vietnamese communists were forced to abandon the path of socialist economy, this argument has persisted, although it must be added that there were “some mistakes” in the revolutionary process.

The familiar story goes: after the failure of the Yen Bai uprising (1930) by the Vietnamese National Party, no force other than the Vietnamese Communist Party led the people in the struggle for “independence and freedom.” Therefore, the “communist path” of Vietnam from the 1950s to the late 1980s was a necessity. Political history serves as the framework for other fields of history. Consequently, we can observe this kind of historical narrative appearing in every aspect: not only in politics but also in economic, social, cultural, literary, ideological, and educational histories.

This narrative of “the inevitability of the socialist revolution in history” can only hold its ground when and only when it focuses solely on the history of warfare, excluding the history of ideology and society. It disregards the fact that every war is carried out by a certain social force with a specific ideological system.

The “great autobiography” of “the inevitability of the socialist revolution in history” leaves behind many unexplainable fragments. When the history of ideology is examined in relation to political, economic, and cultural history, the once coherent historical picture in Vietnam loses its completeness.

Among various aspects of societal organization, legal ideology and the establishment of a legal system are crucial issues. They determine the functioning of the political system, economic and social forces, and, based on these, the operation of the education system to produce corresponding individuals.

This series of articles briefly introduces the republican perspective on jurisprudence in Vietnam after the August 1945 revolution, the debate over the choice between two paths—communism and republicanism—in the late 1940s within the Democratic Republic of Vietnam government, and the choice of the communist legal model in the early 1950s.

We believe that the transformation of legal ideology from the republican spirit to the communist spirit during the period of 1945-1954 is one of the direct causes of the intense political and social upheavals in Vietnam during this era, leading to the subsequent historical developments. In these articles, we will analyze the developments of legal ideology. In the subsequent articles, we will examine the international relations and political forces in Vietnam that propelled this transformation of legal ideology.

Decree 13 and the Autonomy of the Legal System

Right after September 2, 1945, President Ho Chi Minh drafted a guiding article on constructing the administrative machinery of the new regime: “The government is the servant of the people.” The article affirms:

“The People’s Committee is different from the old rotten councils; it will perform actions beneficial to the people, without infringing on justice or the freedom of the people. It rigorously avoids arbitrary arrests and beatings, improper confiscations of property. The People’s Committee exercises the utmost prudence in using public funds and does not dare to recklessly spend money on frivolous matters like eating and drinking.” (Newspaper “Cứu quốc,” Issue 46, September 19, 1945)

Naturally, a system of administration that “does not infringe on justice or the freedom of the people” can only be established through the creation of an independent legal system.

On January 24, 1946, Ho Chi Minh issued Decree 13, in which he emphasized the autonomy of the legal system:

“The Court of Justice shall be independent of administrative agencies.” (Article 47)

“Each Judge in a case shall decide according to the law and their conscience. No authority shall directly or indirectly interfere in the work of judging.” (Article 50)

Article 25 stipulates the oath of office for the Associate Judges of the court:

“I swear before Justice and the people that I will carefully consider the cases brought to trial, not accepting bribery, reverence, fear, self-interest, or personal enmity, and I will uphold justice and impartially determine all matters.”

Thus, differing from the concept of legal service for “class struggle” held by the communists since 1948, limiting the function of law within the scope of “punishment,” this Decree 13 of 1946 emphasized that the role of the court (legal system) was not only “punishment” but also broader: the protection of justice. Linguistically, in the aforementioned oath, “Justice” is placed before “the people.”

Article 47 of the Decree fully expressed the spirit of the republican legal system of the 1946 period:

“The Court of Justice shall be independent of administrative agencies. The Judges shall only uphold the law and justice. Other agencies shall not interfere in the work of Justice.”

Subsequently, the 1946 Constitution (passed by the National Assembly of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam on November 9, 1946) highlighted the independent legal system:

“During trials, judges shall only obey the law; other agencies shall not interfere.” (Article 69)

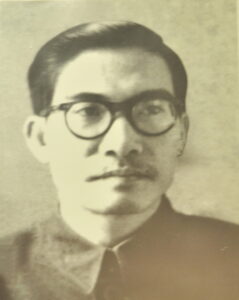

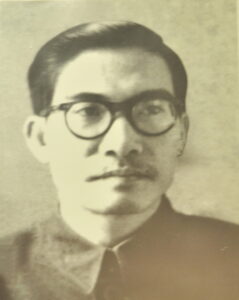

Vũ Đình Hoè, 1912 – 2011, Minister of Justice of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam from 1946 to 1960. (Image: Official Portal of the Ministry of Justice of Vietnam)

Independent Judiciary and the Spirit of the Republic

Republic’s intellectuals participating in the machinery of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, particularly figures like Vu Trong Khanh, the first Minister of Justice, played a significant role. He was the true author of Decree 13 and contributed significantly to the drafting of the 1946 Constitution.

The republican spirit towards the legal system established a democratic façade for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, providing the contemporary Vietnamese people with a legal system to protect justice amidst wartime conditions.

On February 15, 1948, Vu Dinh Hoe, the Minister of Justice, stated in his “Report on One Year of Resistance Activities of the Ministry of Justice” that during wartime, in some areas, certain administrative officials abused their power, arresting innocent people, torturing, and unlawfully imprisoning them.

The report cited an instance when the French attacked southern Ha Dong in April 1947; many local officials abused their authority or took advantage of the wartime situation for personal revenge. They arrested individuals unlawfully, subjected them to torture, and executed them brutally.

However, Regional Courts 2 and 11 reinstated justice, releasing many unlawfully detained individuals, and punished officials involved in illegal arrests and torture. According to the report, Regional Courts 2 and 11 sentenced 15 people to death, including some members of local resistance, self-defense militias, and military personnel. Notably, even high-ranking officials such as the Deputy Chairman of the Anti-French Resistance Committee, Ung Hoa, were sentenced to death.

The report also mentioned that the Ministry of Justice strictly prohibited torture, conducted thorough inspections of detention camps, and ensured there were no secret prisons in districts and regions.

These efforts, as the report highlighted, helped instill trust in the population regarding the safeguarding of justice and the restoration of credibility to the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

However, the spirit of the republic towards the legal system did not endure for long. Just ten days after the aforementioned report, on February 25, 1948, the Ministry of Justice organized a National Judicial Conference, during which the first directive from President Ho Chi Minh against an independent legal system emerged.

Therefore, in the first two years of its existence, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam accepted an independent legal system and respected the rule of law within the republic. Had this choice persisted, Vietnam could have established an independent legal framework to ensure non-abuse of administrative power, uphold civil rights and human rights, and create a political foundation for building an open society.

However, history took a different turn thereafter…

References

Sherry Jr, Vincent J. The evolution of the Legal System of the Republic of Vietnam . The University of Southern Mississippi, 1973

Tuan, H. P., Nguyen, C., Nguyen, D. L., Khôi, N. L. H., Nguyen, M. T., Minh, N. T., … & Zinoman, P. B. (2022). Building a republican nation in Vietnam, 1920–1963. University of Hawaii Press.

Nguyen, M. T. (2022). The Self-Reliant Literary Group and Colonial Republicanism in the 1930s. Building a Republican Nation in Vietnam, 1920–1963, 61.

Thuy Nguyen; Exploiting Ideology and Making Higher Education Serve Vietnam’s Authoritarian Regime. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 1 December 2022; 55 (4): 83–104. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/cpcs.2022.1819231

Zinoman, P. (2013). Vietnamese colonial republican: The political vision of Vu Trong Phung. Univ of California Press.

Vu, Tuong and Nguyen, Thuy. “Chapter 1 “Doi Moi” but Not “Doi Mau”: Vietnam’s Red Crony Capitalism in Historical Perspective”. The Dragon’s Underbelly: Dynamics and Dilemmas in Vietnam’s Economy and Politics, edited by Nhu Truong and Vu Tuong, Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2022, pp. 25-50. https://doi.org/10.1355/9789815011401-003

Kim, T. T. (2022). Early Republicans’ Concept of the Nation. Building a Republican Nation in Vietnam, 1920–1963, 43.

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago