After 1975

In search of what I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải (Part 6)

Published on

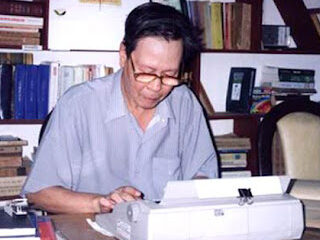

Editor’s Note: The following excerpt is from a memoir by the esteemed writer Nguyễn Mạnh Khải (1930-2008), celebrated as one of the foremost literary figures in communist Vietnam. His lifetime was marked by numerous accolades, including the Le Thanh Nghị Literature Prize (Regional Level III, 1951), the Vietnamese Arts and Literature Prize (1951-1952), the Vietnamese Writers’ Association Prize (1982), the Southeast Asian Literature Award (2000), and the prestigious Ho Chi Minh Prize for Literature and Art (2000). Originally penned in Vietnamese and published posthumously in 2006, this collection has been translated by our editor Vinh Pham. The memoir will be presented in six installments.

Political Essays – 2006

Nguyễn Khải

16.

When I speak, I live and write in a state of detachment, happiness, within a specialized framework of thought, as if I were a liar, deceiving in a brazen, shameless way, living ostentatiously. But those are truthful words, not true for many, but true for me. My fate was changed since the August Revolution of 1945. Nine years of fighting against France may seem long to many, but for me, it was short because I lived in joy, in the extraordinary, and in many hopes.

Many of my comrades in the propaganda office of the military region came from families of small officials, small landlords, received proper education up to elementary school, and carried with them the habits, the customs of civilian life from childhood. They enjoyed observing my reactions when facing the hardships of the resistance war. To them, I seemed like a scholarly child from a noble family who had never experienced deprivation or suffering. My natural actions were often evaluated as requiring much determination, much resolve to accomplish.

I still live as I used to, criticized and scolded in the past, now praised and commended, people buoyant and joyful as if they had entered a realm of bliss, knowing little of want and hardship. If we compare, in the past, I was a mere zero, now I have a name signed under articles, supported, demanded, frustrated, or praised by many colleagues in the office. I have been separated from the crowd to find contentment in myself and to have a bit of a “personal plan” for myself.

As for those who are seventeen years older than me, they have much to compare between what “was” and what “is” now. The “is” of the nation is abundant, but the “is” of individuals, not much remains. Much of historical and social knowledge, philosophy, and literature seem to have been discarded. Social communication skills taught from childhood, when used, appear arrogant, laughable in the context of the resistance war. Living gracefully, respecting others is the lifestyle of a petite bourgeois. Misplaced compassion is seen as a sign of weakness, unreliability. Clever, subtle jokes shine as a gleam of joy in the monotonous, mundane life of each day, but they can easily be misunderstood as a satirical gesture by the educated towards the less educated.

After each training session by our seniors, we feel smaller, fainter, gradually losing our distinctiveness, our uniqueness, to merge into the common stream, into the way of thinking and living of a collective surrounding us. Thus, our individuality has been gradually swallowed by the collective. As for me, how am I? I am fortunate because I belong to the majority, an anonymous community that silently existed for many centuries under the feudal regime. The August Revolution has liberated them from the status of slaves, giving them the opportunity to develop their own talents, primarily in the military field to serve the needs of the resistance. Though most of them only learned to read and write after joining the military, they quickly grasped the construction of a modern army with various departments serving strategic, tactical, and logistical tasks, as they had an ideal model, the modern army of the enemy, with its famous general from World War II.

During the nine years of fighting against the French, the military became the cradle of training, nurturing numerous military talents of the modern era, including artistic and literary talents to serve in the military. It was the most advanced organization in Vietnamese society in the first half of the 20th century. In war, military commanders are the most beautiful, romantic figures as they are people of action, of ensuring victory, always in the forefront. Meanwhile, theoretical individuals are secondary, often just offering supplementary opinions. However, during the years of building socialism, theoretical individuals have the duty of protecting the purity of orthodox theories, and they are respected and have the power to decide the life and death of many.

It’s during these years that many political and literary cases have arisen. Looking back, they seem senseless and absurd, but back then, they silenced many truly talented individuals in various fields because they appeared to doubt the correctness of orthodox thought.

Half of the country has gained independence, yet people’s hearts are shattered due to a lifetime of hard-earned possessions being seized or confiscated by the state, rendering them involuntary paupers. The intellectual class possesses no property beyond their minds, which are now also confiscated by the state. From now on, they can only think and write according to the guidance of a doctrine, a path, unless they want to step on the footsteps of the “Intellectual Bourgeois Group”.

A nation that achieved victory at Dien Bien Phu, yet the faces of its people are worn, eyes dazed, walking hunched like defeated souls. Indeed, the Vietnamese nation won a great victory in the liberation movement, but suffered a heavy defeat in the effort to build a free and democratic society. Escaping the yoke of colonialism, they willingly fell into the shackles of a doctrine that had lost its vitality. Why should our people endure such a tragic fate?

A society in ruins, hearts burdened with personal troubles and worries, yet those who gave their all for the resistance, one way or another. So, how should a writer write? What should they write to create a reality brimming with hope, as demanded by the revolutionary leaders?

17.

The 1950s and 1960s, for me, were years filled with joy. Wherever I looked, I saw myself, my nation. But those were also years of anxiety, fear, and desperation for millions of ordinary people.

My happiness was genuine, and my writings during those years were sincere. Yet, the tears of others were also real, and I knew, I witnessed. Which path should my pen lean towards? It wasn’t until later in life that I realized a writer must heed the call of emotions, of the heart, of the goodness within oneself. It proclaimed what was wrong as wrong, no theory could withstand it.

Furthermore, literature always empathizes with human suffering, human misfortune. It has never sung praises solely for human contentment and success. In various forms of verbal art, humans must confront all contrasting circumstances, occupying almost all pages written, all stages performed. Even when the poor become wealthy, the downtrodden enter a world of opulence, lovers endure years of separation before reunion, stories and plays must end promptly.

It concludes the artistic phase to embark on the phase of eulogy, the world of contentment of monotony, the non-artistic phase. But leaders prefer the non-artistic phase, awarding prizes and medals to authors only to reward that dull, tasteless portion. This perception of reality, full of romanticism, has skewed the examination and behavior of many generations of readers, especially those who come of age amidst the myriad transformations of life. They possess the capability to only critique literature through the lens of the orthodox political route, wondering why a beautiful life is depicted so negatively.

How can they dare to argue? Let time and experience silently defend their perspective over the years.

18.

A society that doesn’t understand itself, where each individual doesn’t truly understand themselves, where right and wrong, noble and base, values all become tangled, starting from the imprecision of language.

The opening verse of the Old Testament reads, “In the beginning was the Word…” Language forms this civilization, for it can preserve and transmit the accumulated experiences of generations to come. As our ability to perceive reality becomes more accurate day by day, human choices become more objective and effectively adapt to the ever-changing environment and social circumstances.

Yet, surprisingly, language remains the weakest aspect in the upper echelons of socialist societies. The citizens of these nations use language to conceal rather than communicate, or communicate through concealment, saying things that are not what they seem! It becomes a rigid shell, guarding against any uncertainty, resisting the habit of scrutinizing the words spoken by citizens of any authoritarian regime.

This protective mechanism is most evident in both high-ranking leaders and low-level officials working in positions of power. They speak in a rigid language drained of vitality, a language devoid of life, a “wooden” language that can fill an entire session without conveying any new information. Press conferences, commemorative speeches, Party reports, government statements, and parliamentary addresses—all employ vague, personality-lacking, and responsibility-avoiding language.

Those in the highest positions of power, as well as those at the lowest, know how to speak vaguely, with vagueness being seen as certainty. And lying, blatant lying, needs no concealment. They know that speaking lies won’t change anything since no one believes them, yet they continue to speak.

They talk about democracy and freedom, about concentration and democracy, about the people being the masters of the country while those in power are merely the servants of the people. They talk about justice, selflessness, ideals, and the determination to advance the country toward socialism. They lie profusely, unabashedly, without a hint of shame, without fear, because listeners rarely question back, lack the habit of retaining explanations and promises for verification.

Or questioning and verification are forbidden, considered taboo, prone to calamity, so not questioning becomes a means of self-preservation. The speaker talks into emptiness, and though the listener is present, they only hear the echoes of that emptiness.

Communication has turned into non-communication, speaking for the sake of speaking, as if humans were not meant to speak. In truth, speaking this way still leads to understanding. The ones in power know that the people are highly dissatisfied about many things, and the people know that those in power are lying; looking at reality, it’s clear they are lying. But let them with their deceptive words, and as for us, the people, we shouldn’t question whether what they say is true or not. Let’s just follow our own intentions, and we will also lie, conceal, if there’s a chance that those in power inquire.

In hundreds of memoirs written by cultural figures, political activists, and numerous leaders, we can’t truly fathom how many separate worlds they inhabit, how many individual worlds they possess. The smaller their personal contributions, the more significant their collective impact, their names grow minuscule, almost insignificant, whereas the unnamed enshrouds all, vast but also formless, hazy and indistinct, present yet absent, that collective entity avoids responsibility towards anyone, its identity elusive.

19.

In such a societal and political context, it is natural for individuals to somewhat lose their sense of self. Writers are specialized researchers of personal matters, delving into the nuances of emotions along with their infinite variations across different circumstances and eras. However, even reading the memoirs of writers can be lackluster. They tend to showcase their own persona in encounters with elder colleagues and friends within their profession, discussing mostly trivial matters, daily routines, and failing to address the zeitgeist, the sentiments towards the times, and the essence of their profession within those times.

The realism and historical significance of an era become faint and simplistic, almost devoid of the ability to transmit the true values of that time to future generations. It’s a regrettable fact, for if the witnesses remain silent, history cannot express its authentic voice. As time passes, darkness shrouds, oblivion sets in, leaving only the milestones of achievements while the silent struggles have shattered many individuals, so that they become themselves, sacred entities, monuments preserving the spiritual wealth of a nation, a lineage, forever nurtured and developed in harmony with the evolution of the nation and the era. Yet literature and philosophy have not delved into this aspect, nor have the humanities.

Even though not spoken about, not permitted to be spoken about, that eternal flow continues to be quietly unblocked by millions. They nurture it, enabling Vietnamese talents to continually emerge, sometimes in this field, sometimes in another. A nation without exceptional and talented individuals representing its community is a misfortune, creating a gap in the historical survival of each individual. Future generations must bridge it in some way, starting again from the political and societal environment, from a society that balances tradition and modernity, aiming for individual development and integration into the cultural sphere of the region and the world. A distinct culture, with idealistic goals, within a stifling social atmosphere overshadowed by power’s omnipresence, determining everything, what will be the fate of individuals?

Examining Russia in the 1990s makes this clear. They escaped the veil of totalitarianism to see the true light of democracy and freedom. Who wouldn’t think they had the chance to take long strides, unshackled from all constraints? Russia will forever be a superpower due to the nation’s greatest challenges being wars and revolutions, both of which it has weathered while its vast expanse and boundless potential, material and spiritual, remain. In a few decades, Russia might reach this state, but in the short term, it’s impossible. The reason is simple: economies can recover quickly, but human beings need much more time to regain what has been lost.

The personal scope of Russians over nearly a century under the Soviet regime has contracted significantly, even as they lived, studied, and worked in the conditions of a civilized society. It’s regrettable that their civilization is a self-formed one detached from human civilization at large, based on standards that the Russian soul could not accept or evolve with. Moreover, over nearly a century, Russians gradually lost the habit of independent thinking, independent decision-making, resistance, and safeguarding truth. People became accustomed to living in a crowd, a collective, a flock, without the opportunity and encouragement of society to create individual portraits with differing thoughts, philosophies, and ways of life. Anything deviating from the norm is condemned, while uniformity is praised. Because differences are hard to unify, while similarities are easy to follow, obeying all orders. Rulers would find it much easier and more leisurely to lead a nation organized like a military camp. They would have extra time to write poetry or novels, enjoying both the present and the future. But leading a civil society of free citizens entails hundreds of daily tasks, each requiring intricate solutions, necessitating dialogue, equal debates, negotiation, and perpetually changing positions that may not align with public opinion. And all actions must adhere to the constitution and undergo societal scrutiny through the media. Not only must the leaders be held accountable for their responsibilities, but their private lives must also be closely monitored to prevent ethical violations. In civilized societies, those in power are bound by many laws, restrictions, the ones with the least freedom, while the general populace is protected by the law in all respects. The less restricted, the better, and the more freedom, the better.

Only a society structured in this manner respects individual positions, where value lies in having a strong, vibrant self, full of vitality and creativity. Therefore, every individual must strive to cultivate their unique traits, their own beauty, and ensure that their descendants and heirs become renowned families, famous lineages, pillars supporting a nation. A totalitarian regime, when faced with significant changes, usually cracks, from cracks to collapse. Time moves swiftly, as its only support is the power of a party, lacking the spiritual foundation of an entire nation. A political system existing for almost a century, or half a century, is already quite long, creating generations that have shared with it, borne children with it, yet when it dies, not a single tear is shed. Some may even trample upon its just-deceased body before continuing their journey. It is clear that it had become an anomaly, a monstrosity, a calamity, and the passage of time gently removes it, an extraordinary stroke of luck without even having to spill blood. It can be concluded that whether a political regime is considered civilized or outdated, whether it will exist for the long term or only within a moment in history, depends on whether the ruling Party truly respects human rights, whether individuals with differences, reactions, and acts of nonconformity are given a significant place in the constitution. For the spiritual strength of every individual, nurtured and developed in freedom, is the most solid foundation of any political system. As long as it remains, one can confidently overcome the unforeseen challenges of the times and continually progress forward.

Written in District 4, Ho Chi Minh City, on May 27, 2006.

You may like

-

In search of what I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải (Part 5)

-

A History of Legal Thought in Vietnam, 1945–1956 – Part 1: The Republican Spirit, 1946

-

In search of what I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải (Part 3)

-

In search of what I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải (Part 2)

-

Dust Child (Book Review)

-

In search of what I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải

Reflections on New Era of National Rise by Vietnam General Secretary Tô Lâm

Of Space & Place: On the Nationalism(s) of Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s “Our Ghosts Live in the Future”

Postwar Music In Vietnam And The Diaspora

Translation: The Decision in 2013 of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Certain Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform

Thủ Đức Demonstration High School: A Modern Educational Policy and Teaching Method of the Republic of Vietnam

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years agoRethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

-

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years agoDeporting Vietnamese Refugees: Politics and Policy from Bush to Biden (Part 1)