In simplest terms, the Government Committee for Religious Affairs is the “church” of all churches in Vietnam.

By Thai Thanh

As you read this article, the Government Committee for Religious Affairs is burning through its 64.9 billion dongs (US$2.8 million). Though details of its budget are not made public, we know only 60.7 billion dongs is used for committee activities.

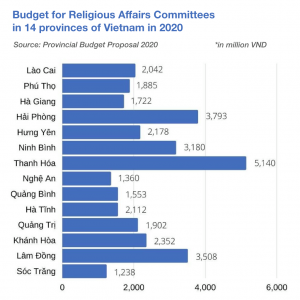

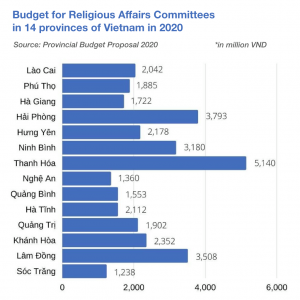

At the local level, Luat Khoa has read through all 2020 budget estimates for Vietnamese provinces and cities, but only 14 provinces have enumerated the amounts distributed to their provincial and municipal religious committees.

In 2020, the religious committees of these 14 provinces and municipalities were provided 33.965 billion dongs. If this number is extrapolated to include all 63 cities and provinces, the approximate total would reach more than 152.840 billion, equivalent to about 60 percent of the 2020 budget for Vietnam Television (VTV).

Phu Tho Province has earmarked 600 million dongs of a budgeted 1.885 billion dong (~78,000 USD) to celebrate festivities and welcome religious dignitaries.

In Thanh Hoa, the provincial religious committee is allotted 5.14 billion dongs, five times the amount given to the province’s SOS Children’s Village; what this money is used for, however, is not publicly disclosed.

(Source: estimated 2020 provincial budgets; Unit: million dongs”)

The numbers above do not include the budgets provided for hundreds of religious affairs offices at the urban district, district, and provincial city levels.

But what does the Government Committee for Religious Affairs and local religious offices do anyway, and are they worthy of taxpayer money?

Back then, back then…

According to the Government Committee on Religious Affairs, the forerunner to the committee was established in 1955 as the “Central Committee on Religion”, directly responsible to the prime minister’s office.

At the time, the task of this committee was to: “Network with religions, and in particular, implement their abilities to mobilize”.

But given the partition of the country at the time, in what ways did this committee “network” with and “mobilize” religions?

Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh has written in The History of Vietnamese Buddhism that in the north, no Buddhist periodicals were allowed to be published, no Buddhist institutes were allowed to accept disciples, no prayer books were printed, orphanages were shuttered, monks under the age of 30 had to give up their robes and don army fatigues or peasant garb to produce (for the state), churches no longer had anything with which to practice and their land had to be “donated” to the state in order to build socialism. [1]

Monks who disagreed with the government were quickly isolated until their deaths, as happened with the Venerable Thich To Lien, Venerable Thich Vinh Tuong, and Venerable Thich Tri Hai.

In 1975, this northern tradition of controlling and subjugating religion was applied to the south. Scores of self-immolations by monks and nuns occurred to protest the discriminatory religious policies of the new government. Arrested monks were sent to re-education camps, tortured, and some even died in prison, such as the Venerable Thich Thien Minh. Others were confined to wheelchairs after their time behind bars, such as Venerable Thich Tri Quang.

Up until the late 1980s, the government saw religion and popular faiths as impediments on the path to socialism. Hoa Hao Buddhism and the Cao Dai religion were seen as “heresies”, tools of foreign countries.

It was not until the 90s that the Communist Party of Vietnam began to accept that religious morality was compatible with “Doi Moi” policies.

The Government Committee on Religious Affairs at the time had the dual task of controlling and utilizing the power of religion; ancestor worship was no longer seen as superstition. Boat people were called to return home to pay respects and send foreign currency to relatives.

By the late 1990s, the Cao Dai religion and Hoa Hao Buddhism were both begrudgingly accepted by the state after millions of followers had suffered more than 20 years of government discrimination.

And now, and now…

Three recent activities carried out by the Government Committee on Religious Affairs give us a good overview of what the body does currently, outside of its tasks of issuing regulations and controlling the publication of religious works.

The first has to do with Dinh Quang Tien, the head of Cao Dai Affairs, meeting with the Tien Thien Cao Dai Church to prepare for the All-sect Congress of Nhon Sanh Representatives.

According to the Government Committee on Religious Affairs, during this meeting, Mr. Tien directed the church’s internal affairs, “building regulations regarding public dignitaries and functionaries and regulations resolving petitions and complaints; and publicly electing dignitaries with sufficient qualifications for the Church’s Senate, Standing Committee, and Chambers.”

The second concerns deputy head Tran Thi Minh Nga chairing a seminar on “Deviance within Religious Activities in Vietnam Today”, with the participation of the Fatherland Front, the Ministry of Public Security, and the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Travel.

Not only does it control religions within the country, but the Government Committee on Religious Affairs also extends its arm overseas.

On June 18, 2020, leaders of the Government Committee on Religious Affairs and the State Committee on Overseas Vietnamese held a meeting regarding the religious activities of the five million Vietnamese living overseas.

During this meeting, the Committee confirmed that the latter organizes annual trips overseas to “meet with communities, understand their sentiments and aspirations, exchange views with local authorities, and suggest ways to help Vietnamese communities with religious and spiritual activities”.

On the Committee website, its regularly-posted activities include organizing conferences and visiting local and overseas locations to conduct business with religions and the relevant city and provincial authorities. However, this committee does not publicize its budget as other bodies do.

In its 2020 budget estimate, this committee is the only body in the Ministry of the Interior to provide 1 billion dongs for environmental protection activities. A portion of this money appears to be earmarked for the “National Conference on the Role of Religion in Protecting the Environment and Responding to Climate Change”.

Today, the Government Committee on Religious Affairs has become the “Church” of all churches in Vietnam, at once interfering in the internal affairs of religions while also trying to determine the “religious standards” for society.

Different from democratic countries, where religious organizations operate independently, religious organizations in Vietnam that want official recognition must operate as though they were a government body. On that front, the Government Committee on Religious Affairs functions as an intermediary for the state to control religious activities.

Laudable “achievements” that have yet to be lauded

The Government Committee on Religious Affairs also has its share of achievements that have not been shared on its website.

Currently, in Thailand, there are more than 1,000 Montagnards who are religious refugees. They fled their villages in the Central Highlands with their families and went to Thailand after being harassed and oppressed, and some were even jailed for many years for wanting to practice their religions freely or demanding the return of land to locals. Some went separately with their families, while others traveled together in large groups; some even had the misfortune of falling victim to human trafficking networks.

In Dien Bien, the authorities forced residents to sign a pledge renouncing the “Gie Sua” religion. A lieutenant colonel from a provincial border guard post stated that he went from house to house, rationalizing the reasons, and then asked residents to sign a pledge renouncing the religion.

The Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam, established in 1964, was no longer recognized by the government in 1975. Leading members of the church were closely monitored; Venerable Thich Quang Do was under surveillance until his death, and Buddhist temples regularly faced harassment from the authorities.

In An Giang Province, independent Hoa Hao Buddhists organize every year to mark the day the religion’s founder disappeared from his home. Many scuffles have broken out between independent Hoa Hao Buddhists and police, with many followers handed lengthy jail sentences for “obstruction of officials”.

Independent Cao Dai followers are struggling with “state-run Cao Dai” to protect the former’s remaining temples. On June 18, 2020, in the city of Tuy Hoa, Phu Yen Province, “State-run Cao Dai” tried to confiscate the Hieu Xuong Temple, which belonged to independent followers.

From 2009 to 2019, the number of followers of the Cao Dai religion and Hoa Hao Buddhism has decreased dramatically.

The Cao Dai religion has lost approximately 76 percent of its followers. Of approximately 2.4 million followers in 2009, only 556,234 remain, according to the 2019 Census.

Hoa Hao Buddhism has lost nearly a third of its followers compared to numbers from 2009. Follower count has decreased from 1,433,252 in 2009 to 983,079. During his return to Vietnam in 2007, Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh suggested that the state dissolve both the Government Committee on Religious Affairs and the police division overseeing religion because they did more harm for religion than good.

He stated that this police division and the Government Committee on Religious Affairs were erroneous emulations from China and lamented that the Vietnamese government still held onto them.

Note

1. The original Vietnamese version of this article is on Luat Khoa Tap chi. Translated by Will Nguyen.

2. Picture: Leaders of the Government Committee for Religious Affairs (from left: Committee head Vu Chien Thang, and deputy heads Nguyen Anh Chuc and Tran Thi Minh Nga). Photo source: Government Committee for Religious Affairs.

Reference

[1] Việt Nam Phật giáo Sử Luận (Translated: The History of Vietnamese Buddhism), Nguyễn Lang (pen name of Thich Nhat Hanh), p. 744.

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

After 19752 years ago

After 19752 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy6 years ago

Politics & Economy6 years ago

Society & Culture6 years ago

Society & Culture6 years ago

ARCHIVES6 years ago

ARCHIVES6 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Vietnamese-America5 years ago

Vietnamese-America5 years ago