Editor’s Note: This interview with our Editor-in-Chief, Tuong Vu, was initially published on October 4th, 2023, by the Center for Advanced China Research. The interview has been reformatted for publication on this site. Click here to see the original article.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

University of Oregon Professor Tuong Vu talks to CACR about the state of Vietnam’s relations with China and the United States, as well as the challenges facing the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. (October 4, 2023)

Tuong Vu is Professor of Political Science and Director of the US-Vietnam Research Center at the University of Oregon. He has held visiting appointments at Seoul National University, Princeton University and National University of Singapore, and has taught at the Naval Postgraduate School. Vu is the author or co-editor of nine books, including: Republican Vietnam, 1963-1975: War, Society, Diaspora (Hawaii, 2023); Building a Republican Nation in Vietnam, 1920-1963 (Hawaii, 2022) and Vietnam’s Communist Revolution: The Power and Limits of Ideology (Cambridge, 2017). He has also authored numerous articles and book chapters on the politics of nationalism, communism, revolution, and state-building in East and Southeast Asia. He serves on the editorial or advisory boards of several journals such as Pacific Affairs, Journal of East Asian Studies, and International Journal of Asian Studies.

…

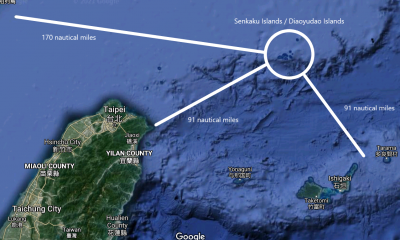

In your view, what is the real significance of the Vietnamese regime’s contestation of areas of the South China Sea with China? Are Vietnam’s protests, claims, and occasional clashes at sea a pro forma cover for a deeper, unspoken acceptance of the fact that China can do what it wants? Or is the regime serious about stopping Chinese activities in its exclusive economic zone and other intrusive and provocative behaviors?

Up to the early 1970s, when Vietnam was divided, the communist regime based in North Vietnam trusted China as a communist brother who selflessly assisted North Vietnam in its revolution to unify Vietnam under communist rule. With that mentality, Hanoi readily and openly acknowledged Beijing’s claims of sovereignty over the entire South China Sea. In fact, most islands in the South China Sea at the time were under the control of the South Vietnamese government, which North Vietnam sought to defeat.

But Hanoi leaders were infuriated when China welcomed Nixon to visit in 1972, considering that a betrayal to the cause of world revolution. That was why the bilateral relationship deteriorated and the two countries fought a border war between 1979 and 1989. In 1988, Chinese naval forces seized several islands in the Spratlys under Vietnamese control and slaughtered 79 Vietnamese soldiers, who, curiously, had earlier been ordered by Vietnamese leaders not to fight back.

Why did they do that? New leaders in Hanoi since 1986 feared the collapse of their regime like other communist regimes in Eastern Europe, and they sought and achieved peace and geopolitical support from China by downplaying the conflict over contested sovereignty claims in the South China Sea.

Vietnam’s policy of absolute deference or non-resistance to China continued until the 2010s, when China encroached more deeply into Vietnam’s claimed territorial waters, especially into the areas where foreign petrol companies have their oil and gas offshore drillings that earn Vietnam billions of dollars annually. The Chinese move sparked strong anti-China protests in Vietnam, the first of which erupted in 2007, which grew to weekly protests in Hanoi for 3 months in 2011. Protesters demanded their government stand up to China. When they were suppressed, protesters accused the government of kowtowing to China at the expense of national interests and demanded regime change and democratization. It was only in 2014 that Hanoi became more defiant towards Beijing.

Even so, the Vietnamese government would never, ever go to war with China over the South China Sea. Hanoi cares more about regime security than about national sovereignty in the South China Sea, and appears defiant to China only to soothe domestic criticisms. Similarly, Hanoi has moved closer to Washington in hopes of using Washington to restrain Beijing, not to form an alliance with the US to contain China. I stressed this point in an article that I wrote about Vietnam’s 2019 White Paper.

Can you talk about the political significance for Vietnam of its economic and trade relationship with China? Have economic links (and China’s proximity) led to concerns in Vietnam about China’s political influence in the country?

China is Vietnam’s largest trade partner, and the volume of trade between two countries dwarfs those of Vietnam’s other large trade partners, such as the US, South Korea, the EU, and Japan. While Vietnam has always had trade surplus with the US and the EU, it has consistently had a trade deficit with China (and to a lesser extent South Korea). In fact, the surplus from its trade with the West is about the same as the deficit it has with China and South Korea.

China is a critical source of raw materials (cotton for example) for many Vietnamese industries, and Vietnam is where local low-skilled workers assemble Chinese (and South Korean) intermediate products for exporting to the West. But Vietnam can turn to other countries for raw materials, so the economic leverage China has over Vietnam is not indispensable. You should read a book I co-edited that just came out with a press in Singapore; it has great analysis of the Vietnamese economy and the role of China.

What’s politically significant is that Vietnamese officials and entrepreneurs love to do business with Chinese firms and welcome aid and loans from the Chinese government since the Chinese are known to be generous with under-the-table kickbacks and Chinese aid does not have attached strings such as labor standards or transparent financial accountability. Unlike the officials, close economic links and China’s proximity have generated deep fears and concerns among ordinary Vietnamese, especially the critics of the government, and have fueled the largest nationwide protests ever in contemporary Vietnam in 2018 when the government was about to pass a law for special economic zones along the coast of Vietnam that critics suspected to cater especially to Chinese businesses. In the aftermath of those protests, which were quickly and brutally put down, the government announced that the draft law would be subject to further study. The draft law was then dropped from the legislative agenda, but the zones are reportedly still being built without the law.

How substantive, in your mind, is the warming of ties between Vietnam and the United States? Do you view this as a development that could continue to deepen to the point that there could be an alliance-like relationship in the foreseeable future? Or do you see systemic obstacles to a deeper relationship developing?

The warming of ties between Vietnam and the United States may take years to become substantive, and much depends on how China treats Vietnam and on what the US can bring to the table. The US has desired a closer relationship with Vietnam for two decades, but Vietnam has been unwilling and only moved a little closer whenever feeling threatened by China. Vietnam now has agreed to upgrade the relationship as the US wishes, and (Hanoi thinks) the ball is now in the US’ court.

Assuming China does not take any drastic actions in the South China Sea in the near future, the US must offer Vietnam significant benefits for substantive progress in the bilateral relationship, such as extremely good deals in weapons and technology transfers (not necessarily directly from the US, with whom Vietnamese officials would not be able to demand kickbacks, but with US allies like South Korea and Israel who may be more amenable), very generous access to US markets for Vietnamese goods, and a cessation of any harsh criticisms of Vietnam’s violations of human rights.

In your interesting chapter “Persistence Amid Decay: The Communist Party of Vietnam at 83,” you cited research from 2010 to point out that “the dominant faction in the CPV leadership still views China as a strategi[c] and ideological comrade (Vuving 2010).” Do you think this is still true? Have factions in the government shifted since that time?

Yes, this is largely true today, although less true than it was back then. Regime security remains the top concern of the power elite, but that security may be defined more broadly these days. China has been viewed in more realistic terms since 2014, as I said above. Excessive or public deference to China could lead to irrepressible domestic protests and political instability, thus harming regime security. In addition, the ideological factor has slowly yielded to the money factor. No one knows how much money China is bribing Vietnamese officials but the profits for them to pocket from doing business with Chinese firms must be substantial. If Uncle Sam can outspend Uncle Xi in offering more generous handouts to Vietnamese officials, he would have a better chance today to woo them to support a closer relationship with the US.

It sounds from your chapter as though Vietnam’s coercive apparatus, though large (“estimated to employ every one out of six working Vietnamese (Hayton 2010: 73)”), is not only inadequate to effectively crack down on protests, but also has been unable to prevent an upswing in street demonstrations that have expanded to “national issues such as corruption, police brutalities, abuses of religious freedom and human rights, and the government’s timid reactions to Chinese aggressive claims of sovereignty over the Spratlys and Paracels in the South China Sea.” Given that you wrote this in 2014, can you tell us if this is still true today?

The arrival of the internet and social media fostered the rise of a civil society in Vietnam from 2005 or so until the early 2010s. That caught the security forces off guard. Since then, the Vietnamese government has learned from China and also developed its own techniques of suppression. Under current Party Chief Nguyen Phu Trong, the government has become increasingly repressive, enacting a cyberlaw that is quite similar to the equivalent Chinese law, strengthening its control over the internet (in part by forcing Facebook and Google to comply with its demands and in part by creating an army of internet trolls), arresting many critics and giving them long prison sentences, expanding the local police force, and more recently, imprisoning even leaders of the civic environmental organizations which have served as the liaisons between the government and international organizations. It’s fair to say that the government has succeeded in substantially restricting the virtual space for criticisms and that the overall condition for protests is far more limited today. Yet scholars of social movements would tell you that they come and go in waves or cycles over time, and the government’s success at this point will not last forever.

One of your most interesting points was that the CPV “has failed to penetrate new urban areas and private enterprises” and that “involution seems to be the trend, as the party can grow only by sucking from the state sector and the military already under its control but not by expanding its roots into a rapidly changing society.” Two questions: first, in light of the seriousness of this issue, why is it the case that “owners of private businesses who want to join the party are still rarely admitted?” Second, has the failure to penetrate private enterprises led to the creation of a politically powerful business lobby that stands apart from the party apparatus?

First question: I don’t know the answer, but I suspect that the Party issued a decree to allow private owners to be admitted but its central leaders were not wholly or unanimously persuaded about the merit of the move and did not make major efforts to change things. As the decree goes down the administrative level, where personal relationships are more important, local party leaders would not want to open up access to power to private owners unless they are their friends and relatives, which have always enjoyed party membership if they ever wanted.

Second question: There’s actually no “business lobby” in the sense the term is commonly used. Everything is based on personal relationships. Particular entrepreneurs, if they are successful on any scale, must rely on personal relationships with those officials in power. Often times, they are their families. Top officials have commonly had their friends and families open and run businesses, not to make products or services that benefit society but to act as middle men who receive lucrative contracts/bank credits/other favors from the government only to subcontract/transfer them to other private companies for kickbacks. Given the close personal relationships involved, they don’t “stand apart from the party apparatus” but are part of its operation. The networks offer bribes to superiors to get their members promoted to higher positions, and the members in turn repay the networks.

You sounded somewhat pessimistic in your conclusion about the CPV’s ability to “persist amid decay” going forward. Is this still your view? Are there any new challenges or developments that have emerged since you wrote that that have altered the CPV’s ability to retain a monopoly on power?

Yes, it’s still my view. The decay is much more widespread today, despite the apparent strength you see on the surface. The Party’s subtle calibrations of its policy toward China and the US since 2014 have and will help it persist. Yet China’s economic power has recently declined, together with Russia’s international standing and power. Both have been traditional backers of Vietnam to counter US pressure, and their decline exposes Vietnam to greater pressure from the US. (Which was a main reason for the recent upgrading of relationship). The main challenge to the Party comes from inside, as Vietnam’s closer relations with the US will foster changes from within society and greater demands for political freedom.

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago