Joshua Kam

It’s the first thing I notice settling into my booth in this East Village mainstay: a Vietnamese restaurant with not a green-capped sriracha bottle in sight. This shouldn’t surprise me—for two years, Huy Fong, the formidable sriracha giant, has battled crippling supply shortages as climate change decimates the chilies its sauces depend on. Instead, we’ve got Roland Sriracha now, squirted onto our plates from a cheery yellow cap. A listless chinoiserie dragon wraps its coils around the bottle. Unlike the trilingual label pasted on every bottle of Huy Fong’s (Vietnamese, Chinese, and English), Roland’s packaging comes in English: marketable, palatable, safe. And unlike Huy Fong, Roland Foods is not owned by a Vietnamese-American refugee, but by a private equity firm (they have a slogan, I quickly learn: “Investing for Growth!”)

The food at Mme. Vo’s, however, remains delicious. I’ve come off the L-train hungry; we eat through the appetizers, the bánh xèo heaped with fresh greens, the Tet noodles whose recipe, we are told, is easily reproduced at home. I’ll leave it to the experts, whose food issues like clockwork from the swinging kitchen doors. In many ways, this restaurant’s rise and rise typifies a new generation of sleek, chic Vietnamese restaurants. It also reflects shifts in how Vietnamese food is being received, though not only in America.

Vietnam’s growing economic visibility dovetails with culinary visibility, as the labor-intensive, complex work of Vietnamese chefs across the diaspora gains recognition, and commands higher prices. The French are back, apparently, but this time as connoisseurs. The Michelin Guide released its first list of restaurants in Vietnam this year. In Hanoi, Sam Tran and Long Tran’s Gia made it into the list with a single Michelin star, sporting a twelve-course menu in cool dark wood digs. HCM City’s Phở Chào bagged a Bib Gourmand for its clean, clear broths. If anything, the Michelin Guide’s breezy online reviews in English offer a translation for new connoisseurs. But on both sides of the water, the stakes are high for this upscale renovation of Vietnamese cuisine.

Cơm tấm sườn nướng dish (broken rice with grilled meat) from one of the locales in New York City.

This summer, I found myself covering the advent of the Michelin Guide in my home country, Malaysia—another Southeast Asian state anxious to highlight and export its gastronomy. For many, the gold seal of the Guide’s approval of these Southeast Asian mainstays is a point of celebration. Of course, we’ve always had delicious food; it’s just that now the Guide is putting everyone else on. Less salutary is the attendant talk of culinary maturity which Michelin tasters claim to arbitrate. Announcing its entry into Vietnam’s foodways, an article from the Michelin Guide reaffirmed its criteria of excellence, vowing “to settle in mature gastronomic destinations…highlight world culinary scenes and promote travel culture.”

A lot rides on that notion of culinary adulthood. What precisely do we mean by “mature?” Welcome to the grown-ups’ table: you can eat with the French now. American critics employ this language too. Eater in 2021 writes that Vietnamese-American food has at last “come of age”—though what an American means speaking about food from a two-thousand-year old country is beyond me. Do cuisines grow up? Or were they always waiting, like lotuses in the murk, for outside connoisseurs to discover? Nevertheless, inspected by a global gallery of impartial judges, Southeast Asian cuisines are finally passing the test.

Indeed, this test is important for Asian restaurateurs—however condescending the assumptions baked into its criteria may be. A lot is at stake in the world of culinary diplomacy. Thailand has invested aggressively into exporting Thai food abroad, even giving loans and training for Thai émigrés to set up shop in France or America or China. Singapore too has been anxiously rebranding a plethora of dishes as Chinese Peranakan, often effacing the history of ethnic Malay chefs to sell the food of “brown Asians” to outsiders. Both of these countries have marketed deftly to Euro-American palates, and have won the rewards. Bangkok and Singapore have long enjoyed the Michelin Guide’s attention, lavished with stars and expatriate chefs opening restaurants. For rising chefs of Vietnam and Malaysia, these guides are a long-awaited stamp of approval, a showcase to a world that still largely expects these certificatory seals.

In America too, these renovations do similar heavy lifting. Laut, a Malaysian restaurant in Flatiron which has won a Michelin star, serves traditional hawker food. Van Đa, with its Hue Sampler, Madame Vo with its Tet Noodles, and Brooklyn’s Viet-Mex Falansai offer a similar scale of sophisticated American-restaurantness for foods perhaps overlooked in previous, simpler digs. Great effort is taken for Vietnamese food to be understood, and these restaurants have mastered the work of translation. Bánh xèo is a Vietnamese crepe, we are told—and I immediately get the picture. Still, a whole galaxy of flat pancakes can only be gazed upon through the telescopic foods of the French. Why not, for the sake of humor and perhaps sincerity, a Vietnamese-style taco? (They exist and are delicious).

Of course, Vietnamese food is not new in America. But the work of Vietnamese entrepreneurs selling chic bowls of phở in downtown Manhattan or DC or Boston or San Francisco is a more recent project. I suppose we must consider Indochine, which opened its doors in 1984, offering power lunches for the corporate bros of the age. But Indochine and its attendant colonial pretense was the product of white owners, its offerings neatly guaranteed by that whiteness. Shaded by the banana fronds in the wallpaper, the celebrities of the eighties dined in an orientalist paradise, a tropic retreat just off Broadway. No modernity here—nor, visibly, any Vietnamese people. Its cuisine exists comfortably un-peopled. Welcome to the jungle.

The latest push of Vietnamese-owned Viet-American offerings means something quite different. Vietnam features as more than a relic of a colonial past, but a cuisine cooked by people, with a history and an urbane, sophisticated past. At stake is a question of prestige; is our food worthy of commanding the respect and wallets of American eaters? Or are $16-dollar side dishes the exclusive privilege of French and Japanese eateries?

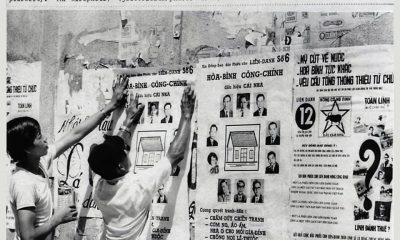

At the heart of these burgeoning new developments—at the extraordinary inventiveness of Vietnamese chefs across the diaspora—is a question of arbitration. It’s about good food, yes, but also about who gets to decide what’s good food. What does it mean when anonymous international connoisseurs suddenly announce what’s what in Hanoi’s street food, or among the Vietnamese fusion bistros of DC? France and America have had a long history of deciding what’s delicious; a long colonial project. For a long time, French colonists in Vietnam, convinced of Gallic culinary primacy, were determined to eat only French goods, however stale: tinned asparagus, sorry cans of cheese. One shudders to imagine whatever 19th-century velveeta the French were coaxing out of tubes. Likewise, wheat was a luxury, one reserved overwhelmingly for white officials and their families. Banh mi—the baguette sandwich that now iconizes Vietnamese food abroad—only appeared after independence. Eating bread was an act of revolt, the flex of a people who would not be told what they could eat.

Some seventy years later, descendants of those connoisseurs are back. Institutions like the Michelin Guide aren’t exactly controlling what Vietnamese people eat, but they are back to discern or endorse the appetites of an ascendant Vietnam’s culinary scene. Street food is in, we’re told—as it is in Indonesia or Malaysia or the Philippines. Some years back, Netflix took us on a whirlwind tour of the banana pancake trail, in many ways pushing back against even older myths of Asian food. Not that the myths are dead; a former server at DC’s Doi Moi said she couldn’t remember how often she fielded the racist questions of customers. “Are you sure this is really chicken?” But even as these older racisms recede, the new myth of Asia, as a paradise of cheap street food in listless urban alleys, fulfills another fantasy. Discovery and connoisseurship are the real prize; Michelin, the Tiktok kids, Zagat and the rest—everyone’s in search of the next hot pot, the next hot spot. White people (among others) have discovered the exquisite pleasure of saying, Oh, I know a place.

But how does the arbitration process work? In the case of the Michelin Guide, this process is famously opaque. Its anonymous tasters crisscross the globe, taking notes of restaurants at all budgets now—from hole-in-the-wall eateries to fifteen-course prie-fixes. But its results—not least of all in Malaysia—might surprise eaters actually from those cities. Nam Heong Chicken Rice—a ubiquitous but not particularly palatable franchise, won a Bib Gourmand. Who’s next on the list? KFC? The seafood supreme at Subway? Did the Guide’s taste-testers venture into the thousands of bespoke hawkers selling chicken rice in kopitiams across Kuala Lumpur? As much as the Michelin Guide boasts in its objectivity, these projects are expensive, requiring corporate sponsors, millions of dollars, and a cartload of press publicity. As much as we’d like to believe in fair judges, I can’t help but be a little puzzled by the results.

Anăn Saigon in Ho Chi Minh City. One of the four restaurants in Vietnam that received a Michelin star. Photo from Condé Nast

I cannot judge the Michelin Guide’s estimations of street food in Vietnam; I don’t dare. It takes some audacity to walk sight-unseen into a country that isn’t yours, with the sole goal of deciding which of its restaurants deserve esteem. Though Vietnam is proud to have four restaurants received the sought stars, which is no small feat, I assume, that as in Kuala Lumpur, the local connoisseurs have their own favorite places, their own secret spots, a circulation of foods and foodways only for people in the know. And perhaps it’s just as well that our best joints are left undiscovered, across Southeast Asia. I’m gatekeeping my favorite curry noodles to the grave. I understand the national project of upscaling your own cuisine to American diners; it’s a difficult feat. So too is inviting French diners to taste their way through Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh City, deciding what they liked or didn’t. Vietnamese and Vietnamese Americans have achieved both with ingenuity, patience, and a lot of hard work. These projects can do real good, as global eaters begin to comprehend the craft and dignity of Southeast Asian cuisines. Surely this food is worthy of our awe, not just an astonishment at the conversion rate. Everything is so cheap there. It’s never been cheap—not for the cooks who produced this food. It’s just cheap for the visitors.

Selfishly, un-patriotically, I can’t help but want to keep some foods out of international purview. I want to eat what I’ve always eaten, undisturbed. There’s something special about ordering an off-menu dish in an Asian American restaurant. There’s an intimacy, a connoisseurship acquired by eating the same meal again and again, prepared by the same hands. The same exacting critique that French people have for their own food isn’t learned overnight in Vietnam or Malaysia or Laos or Cambodia. It takes time and knowledge; it demands a palate that’s trained. Most of all, it’s a communal affair, when a cousin or an aunty or colleague nudges you an hour before lunch, saying, “I know a place.” And we know our places. Everyone else is just finding out.

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago