About US

The Neglect of the Republic of Vietnam in the American Historical Memory

Published on

By

Nu-Anh Tran

Editor’s Note: The following text is an essay from an edited volume that includes sixteen chapters by different authors. The volume provides scholarly accounts of how the state of South Vietnam was imagined and produced by internal actors, with the aim of shifting away from the perception of the Republic of Vietnam as purely a US state building project. Notes are reproduced in full.

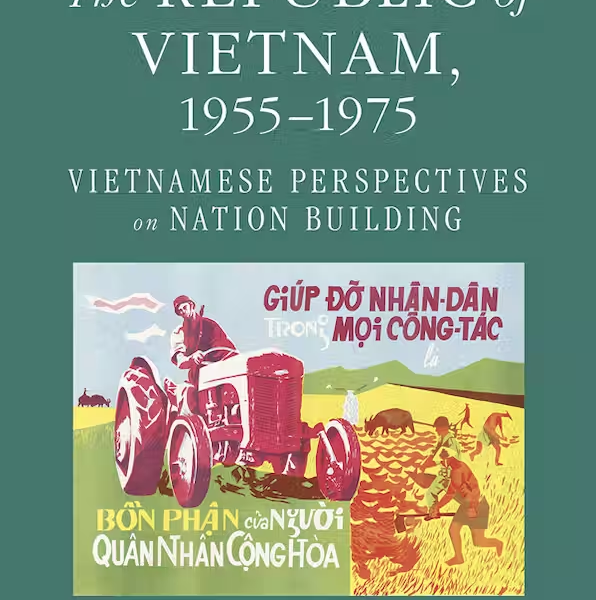

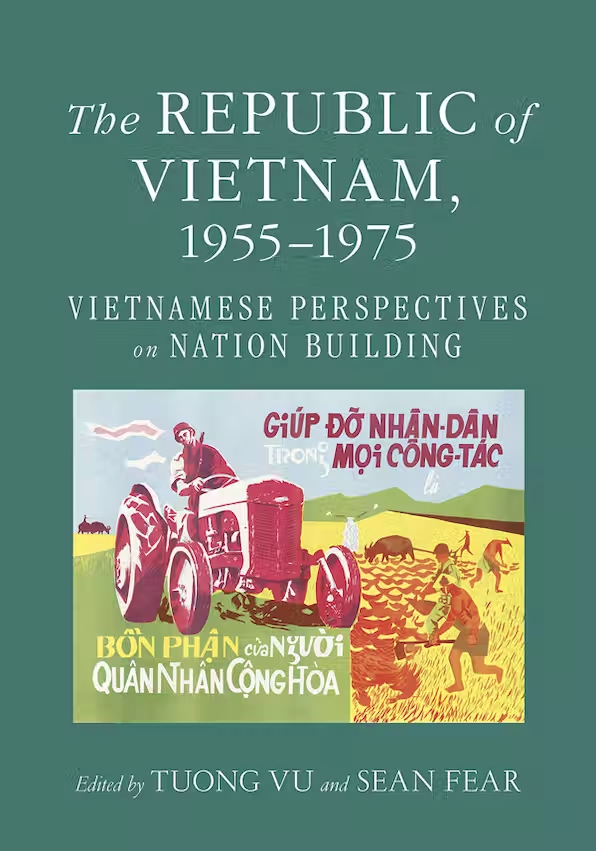

Vu, Tuong, and Sean Fear, editors. The Republic of Vietnam, 1955–1975: Vietnamese Perspectives on Nation Building. Cornell University Press, 2019.

One of the most common grievances I heard growing up in the Vietnamese-American community was that American movies and television did not accurately portray the Vietnam War. I came to the United States as a refugee in the early 1980s, and my family’s first decade in this country coincided with the release of iconic films such as the Rambo series, Full Metal Jacket (1987), Platoon (1986), and Born on the Fourth of July (1989). The war also served as a backdrop or back story for a number of contemporary television shows, including The A-Team (1983–87), Tour of Duty (1987–90), and China Beach (1988–91). My parents and their friends decried the absence of Vietnamese people in popular depictions and were outraged by the portrayal of the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, better known as South Vietnam), the defunct anticommunist government that many refugees still championed. Gathered at the dining table over holiday meals or lecturing me and other children during weekly language classes, my elders would say indignantly, “American movies only show American soldiers, as if they did all the fighting, and we did none.” Someone would invariably add, “And if they show the Vietnamese at all, it’s only the communists. The movies don’t show anyone on our side except for prostitutes, corrupt generals, and cowardly soldiers.” At issue was the very legitimacy of the war. Although my elders acknowledged the shortcomings of the Saigon government, my parents and their friends valorized the war as a nationalist struggle against communism. They especially resented the implicit suggestion the regime was not worth saving, a suggestion that they believed cheapened our plight as refugees and the sacrifices of loved ones who fought for the anticommunist cause. Ultimately, I think the refugees feared that their experiences of the RVN would never become part of the collective historical memory.

I have repeatedly mulled over those many conversations I heard as a child. The grievances of my parents and their friends appear to beg two distinct questions: Why has the anticommunist regime been ignored in the dominant American discourse, and what can Vietnamese-American refugees do to remedy the situation? I want to consider this problem as both a trained historian and a member of the community. This article is a personal reflection and an appeal to other Vietnamese-Americans rather than a work of academic analysis. My elders sometimes suspected that there was a deliberate attempt to silence anticommunist voices, but I believe that the reasons were far more mundane.

Let me begin by briefly discussing the representation of the Vietnamese in American popular culture in the late 1980s and early 1990s. At the time, mainstream film and television focused almost exclusively on the American experience, just as my elders alleged.[1] According to several studies, the media typically relegated Vietnamese people—if they are included at all—to minor characters or shadowy figures. Those affiliated with the RVN were depicted as corrupt, inept allies, while Vietnamese communists were either perfidious enemies or idealized heroes.[2] I have no expertise in American popular culture, but I would wager that the majority of filmmakers were white Americans who were interested in their own stories, and the result was a vision of the war dominated by characters made in the filmmakers’ own image. (I hasten to point out that American movies about other historical events have been and continue to be equally riddled with problems of representation and accuracy.) Perhaps part of the solution is that there needs to be more Vietnamese-American filmmakers. Many members of the community hailed Ham Tran’s Journey from the Fall (Vượt Sóng, 2006) as an accurate portrayal of their experiences, especially the film’s depiction of reeducation camps and the boat people experience. Indeed, Tran’s film was revolutionary as the first full-length narrative film made in the United States to privilege an anticommunist Vietnamese perspective.

The problem of representation extends to the English-language academic research. The Vietnam War has generated a tremendous volume of scholarship, but the bulk of the research has focused on the United States. While a significant portion examines the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV, or North Vietnam) and the communist-led National Liberation Front (NLF, colloquially known as the “Vietcong”), there is very little scholarship on Vietnamese anticommunists and the RVN. Below, I identify four main reasons for the past scholarly neglect and explain how Vietnamese-Americans can help rectify the problem.

The first reason is that the Vietnam War is a research topic that straddles two starkly different fields: American diplomatic history and Vietnam studies. The former is large and robust and has disproportionately shaped academic understanding of the war. Diplomatic historians are Americanists by training, and they study the conflict as an event in the history of U.S. foreign relations. In the past, these scholars have discussed the RVN only as an extension of American foreign policy rather than a distinct unit of analysis, and they argued that the Saigon regime was a foreign creation devoid of indigenous origins.[3] Vietnam studies was a potential corrective to the American-centered research. Students of Vietnam conceptualized the war as an event in Vietnamese history and pointed to the conflict’s inextricable ties to French colonialism, the Vietnamese nationalist movement, and the rise of communism. But Vietnam studies, itself a subfield of Southeast Asian studies, remains underdeveloped and cannot match the influence of American diplomatic history.

Second, scholarly trends within Vietnam studies have mitigated against research on the RVN until recently. American academic research on Vietnam did not begin in earnest until the latter half of the 1960s. This first generation of Vietnam specialists was eager to examine the Vietnamese dimension of the war, but they were selective as to which group of Vietnamese to study. Influenced by growing antiwar sentiments and seeking to explain the strength of the NLF and the DRV, researchers devoted their attention to the communists instead of the Saigon regime. The communist-centric trend continued into the 1980s and produced what has become the dominant historical interpretation.[4] In brief, scholars argued that Vietnamese communism was the direct outgrowth of the colonial-era nationalist movement and that the communists won the war because they were more convincingly nationalist. The narrative cast the communist movement as the main trend in modern Vietnamese history while dismissing the RVN as a deviation. Researchers discussed the anticommunist regime not as a topic in its own right but merely as a foil to the other Vietnamese belligerents.[5] Although the vagaries of academic trends affect virtually all disciplines, the communist-centric scholarship exercised unusual dominance because of the small size of Vietnam studies.

The limited availability of sources was another reason for scholarly neglect of the RVN. For decades after the war, the absence of diplomatic relations between Vietnam and the United States meant that American researchers could not consult the Vietnamese archives. Instead, scholars could only draw on American and French archives, published materials available in Western research libraries, and publications and oral history produced by the Vietnamese diaspora. These sources, although valuable, could not substitute for the RVN’s own documents, arguably the best material for understanding the regime’s identity and aspirations. Finally, the language barrier constituted a serious obstacle. Vietnamese-language skills are essential for conducting serious research on Vietnam, but few American scholars had the opportunity to learn Vietnamese because most universities did not offer any courses in it. Even at institutions that did, the pedagogical quality lagged behind more frequently taught Asian languages such as Mandarin Chinese and Japanese.

Yet the tide of academic scholarship is turning, and prospects for research on the RVN are now brighter than ever. In the latter half of the 1990s and the early 2000s, a young generation of American diplomatic historians began studying Vietnamese just as the reestablishment of diplomatic relations made the Vietnamese archives more accessible. Several of these scholars seized upon the opportunity to examine government documents produced by the RVN as well as rare books and periodicals housed at the regime’s former national library. Other historians explored the DRV’s archives to better understand the inner workings of the wartime government in Hanoi. The new sources facilitated the emergence of a scholarly trend known as the “new Vietnam War scholarship,” which was distinguished by a major conceptual shift. Instead of the American-centered framework, several historians devoted equal attention to both sides of the Washington–Saigon alliance. Whereas earlier research had cast Ngô <&Eth;>ình Diệm as a reactionary mandarin that obstructed American reforms, historians such as Philip Catton and Edward Miller argued that the RVN’s first president possessed distinct ideas for transforming South Vietnam. Catton’s and Miller’s studies found that Diệm and his American advisers disagreed sharply on how to modernize Vietnam, and their differences ultimately led to a breakdown in relations.[6] Jessica Chapman demonstrated that earlier research had failed to appreciate the significance of the Southern sects and their impact on international relations,[7] and Geoffrey Stewart examined Diệm’s largely forgotten civic action program.[8] Quickly following on the heels of these Americanists is an emerging cohort of Vietnam specialists who have made the RVN the main focus of their current research projects. I include in this cohort scholars such as Van Nguyen-Marshall, Jason Picard, Phi Vân Evelyne Nguyen, and myself.[9]

The Vietnamese-American community can contribute to the new Vietnam War scholarship by creating primary sources. I urge everyone who lived under the RVN to write memoirs, to grant interviews, and to share their memories. Although there are many published autobiographies and interviews, most of them feature political and military leaders, almost all of whom are educated men.[10] Valuable as these perspectives are, historians also need to understand the experiences of women, youth, ethnic minorities, artists, journalists, teachers, religious leaders, artisans, laborers, market vendors, cyclo drivers, bargirls, enlisted soldiers, and peasants. Such diverse sources will give scholars a richer understanding of the RVN as a dynamic and complex society, and historians will be better able to examine topics such as popular political attitudes, sexual mores, youth culture, class stratification, urban-rural divisions, and the effect of the war on ordinary people. Personal accounts are also useful in teaching. I regularly assign Vietnamese-American memoirs in my courses on the Vietnam War. Most of what my students know about the war comes from American movies, and the memoirs help my students understand how different Vietnamese groups experienced the conflict.

The prospects for future research on the RVN are partially dependent on the strength of Vietnam studies as a field. I believe the Vietnamese-American community can support the field by teaching our children our mother tongue, by sharing with them our family history, and by fostering their interest in Vietnamese culture. We can also encourage our children to seek out universities that teach about Vietnam and enroll in Vietnam-related courses. The objective is to pique young people’s interest in Vietnam studies and to build a constituency for the field. I myself would not have chosen to study the RVN had it not been for my parents’ captivating stories and their decision to raise me bilingual. In fact, roughly half of the Vietnam specialists in my acquaintance share my background: diasporic Vietnamese who learned the language and culture from their parents. I fully acknowledge the difficulty of teaching a second language and culture without the institutional support of schools, teachers, and textbooks. My late mother, who had no pedagogical training, had to juggle teaching Vietnamese classes with her full-time job and household chores. I have vivid memories of her pausing her lectures on Vietnamese poetry to check the stove or stir the soup pot. I also struggled to learn the language due to the dearth of age-appropriate reading materials and the absence of a sizable Vietnamese-speaking peer group. Nevertheless, our community must shoulder the task of maintaining Vietnamese as a vibrant, living language in the United States because too few universities offer Vietnamese instruction. Beyond our community, we can also support the field by donating to universities and research institutes that promote Vietnam studies.

More broadly, if Vietnamese-Americans want to influence the collective historical memory, then we must value the humanities, the social sciences, and the arts. These are the fields that shape how a society remembers the past. Our community needs historians to interpret our experience, anthropologists to analyze our rich culture, literary critics to keep our long tradition of oral and written literature alive, and filmmakers to tell our stories on the silver screen. The problem is that Vietnamese-American elders often dissuade young people from pursuing those fields in favor of conventional careers in medicine and engineering. My own relatives frowned upon my decision to become a historian when I was in college, and even Vietnamese-American peers puzzled over my choice to major in history, though I was lucky to have my parents’ full support. Some of my Vietnamese-American colleagues recount that their decision to pursue graduate studies in the humanities provoked a family crisis, and their parents responded with lectures, entreaties, and orchestrated interventions. It is understandable that refugees who have weathered profound dislocation would nudge their children into lucrative, high-status occupations. Doctors and engineers certainly do laudable work. But if our community blocks its young people from alternative careers, we are actively contributing to the erasure of our experiences from the historical memory. After all, would Ham Tran have made Journey from the Fall if he had decided to become a pharmacist?

Lastly, we as a community must support intellectual freedom because it is vital to historical memory. Virtually every government in modern Vietnamese history has to some degree suppressed dissent, enforced censorship, and tried to shore up its power by manipulating history. We must recognize that the serious examination of the past will render multiple interpretations. Moreover, the Vietnamese-American community is increasingly diverse, and members harbor varied perspectives on the war and on the RVN.[11] We should choose polite debate rather than trying to silence those with whom we disagree. My elders understood how it felt to be ignored by the dominant discourse and insisted that their perspective deserved to be acknowledged. As we attempt to incorporate our stories into the collective memory, we must also make room for the histories of others. Their viewpoints, like ours, will enrich the understanding of the past.

[1] Oliver Stone’s Heaven and Earth (1993) was the only mainstream American feature film produced in the late 1980s and 1990s that focused on the Vietnamese experience of the Vietnam War.

[2] Michael Renov, “Imaging the Other: Representations of Vietnam in Sixties Political Documentary,” in From Hanoi to Hollywood, ed. Linda Dittmar and Gene Michaud (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990), 255–68; Doug Williams, “Concealment and Disclosure: From ‘Birth of a Nation’ to the Vietnam War Film,” International Political Science Review 12, no. 2 (1991): 37–38; David Dresser, “‘Charlie Don’t Surf’: Race and Culture in the Vietnam War Film,” in Inventing Vietnam: The War in Film and Television, ed. Michael Anderegg (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991), 86–97; Andrew Martin, Receptions of War (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), 99–100.

[3] Gabriel Kolko, Anatomy of a War: Vietnam, the United States, and the Modern Historical Experience (New York: Pantheon Books, 1985); James Carter, Inventing Vietnam: The United States and State Building, 1954–1968 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Seth Jacobs, America’s Miracle Man in Vietnam: Ngo Dinh Diem, Religion, Race, and the US Intervention in Southeast Asia, 1950–1957 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005). See also George Herring, “Our Offspring: Nation Building in South Vietnam, 1954–1961,” chap. 2 in America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950–1975 (New York: Wiley, 1979); Marilyn B. Young, The Vietnam Wars, 1945–1990 (New York: Harper Perennial, 1991); George Kahin, Intervention: How America Became Involved in Vietnam (New York City: Anchor Books, 1987).

[4] For a concise overview of this period in Vietnam studies, see Tuong Vu, “Vietnamese Political Studies and Debates on Vietnamese Nationalism,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 2, no. 2 (Summer 2007): 187–203.

[5] David G. Marr, Vietnamese Anticolonialism, 1885–1925 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971); David G. Marr, Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, 1920–1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980); William J. Duiker, The Communist Road to Power in Vietnam, 1st ed. (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1981); Huỳnh Kim Khánh, Vietnamese Communism, 1925–1945 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982); Carlyle Thayer, War by Other Means: National Liberation and Revolution in Viet-Nam, 1954–60 (Boston: Allen and Unwin, 1989).

[6] Philip Catton, Diem’s Final Failure: Prelude to America’s War in Vietnam (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002); Edward Miller, Misalliance: Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and the Fate of South Vietnam (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013).

[7] Jessica Chapman, Cauldron of Resistance: Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and 1950s Southern Vietnam (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013).

[8] Geoffrey Stewart, Vietnam’s Lost Revolution: Ngô Đình Diệm’s Failure to Build an Independent Nation, 1955–1963 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

[9] For a sample of research by this cohort, see Van Nguyen-Marshall, “The Associational Life of the Vietnamese Middle Class in Saigon (1950s–1970s),” in The Reinvention of Distinction: Modernity and the Middle Class in Urban Vietnam, ed. Van Nguyen-Marshall, Lisa Drummond, and Daniele Belanger (Singapore: Asian Research Institute, National University of Singapore, in cooperation with Springer Publishing, 2012), 59–75; Jason Picard, “Renegades: The Story of South Vietnam’s First National Opposition Newspaper,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 10, no. 4 (Fall 2015): 1–29; Phi Vân Nguyen, “Fighting the First Indochina War Again? Catholic Refugees in the Republic of Vietnam, 1954–59,” Sojourn 31, no. 1 (March 2016): 207–46; Nu-Anh Tran, “South Vietnamese Identity, American Intervention and the Newspaper Chính Luận [Political Discussion], 1965–1969,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 1, nos. 1–2 (February/August 2006): 169–209.

[10] Notable memoirs by diasporic Vietnamese men relating to the RVN include but are not limited to Nhị Lang, Phong trào kháng chiến Trình Minh Thế [The resistance movement under Trinh Minh The] (Boulder, CO: Lion Press, 1985); Bùi Diễm with David Chanoff, In the Jaws of History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987); Đỗ Mậu, Việt Nam máu lửa quê hương tôi [Vietnam, my warring country: political memoirs] (Mission Hills, CA: privately published, 1986); Huỳnh Văn Lang, Nhân chứng một chế độ [Witness to a regime], vols. 1–2 (Westminster, CA: Văn Nghệ, [2000?]); Hà Thúc Ký, Sống còn với dân tộc [Living within the nation] (n.p.: Phương Nghi, 2009); Nguyễn Công Luận, Nationalist in the Vietnam Wars (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012). The most prominent memoirs by diasporic Vietnamese women that discuss the RVN are Duong Van Mai Elliott, The Sacred Willow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); Le Ly Hayslip, When Heaven and Earth Changed Places (New York City: Plume, 2003).

[11] For an overview of recent changes in the composition of Vietnamese-Americans, see An Tuan Nguyen, “More Than Just Refugees: A Historical Overview of Vietnamese Migration to the United States,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 10, no. 3 (Summer 2015): 87–125.

You may like

-

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

Upcoming Event: 6/11/23 50 Years of the Vietnamese Community in the US: From History to the Future

-

Creating the National Library in Saigon (excerpt)

-

Upcoming Event: 5/10/23 Hidden Histories: The South Vietnamese Side of the Vietnam War

-

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 14 Vietnamese Anticommunism

Frustrated Nations: The Evolution of Modern Korea and Vietnam

Lại Nguyên Ân Revives the Portrait of Phan Khôi Once Again

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 22 – Subjects and Sojourners

“First Thắng, Second Chinh, Third Thanh, Fourth Trưởng”: The Four “Incorruptible” Generals of the ARVN

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 21 – Living Abroad

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

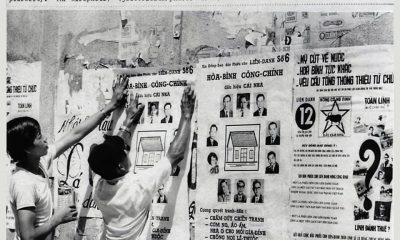

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

National Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoChina’s Recent Invention of “Nanhai Zhudao” in the South China Sea (Part 2: Examining the “Nanhai Zhudao” legal basis)

-

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)