After 1975

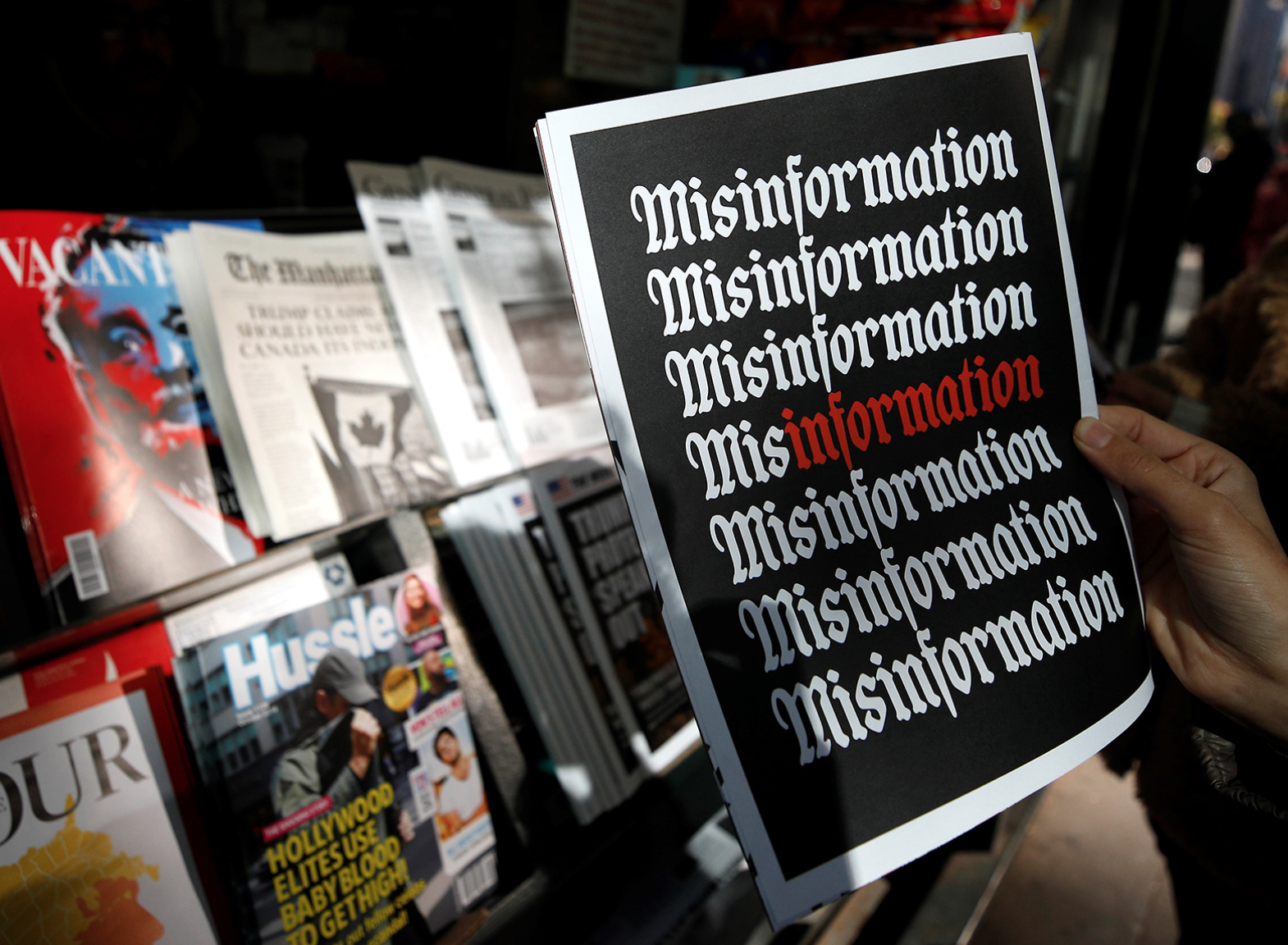

The Misinformation Crisis within Vietnamese American Communities

Published on

Editor’s Note: The following is an abbreviated version of an article published by Political Communication. The authors of the article are: Sarah Nguyen, Rachel Moran, Trung-Anh Nguyen, and Linh Bui. The full report with source materials and research findings can be accessed under its full tittle: “We Never Really Talked About politics”: Race and Ethnicity as Foundational Forces Structuring Information Disorder Within the Vietnamese Diaspora”

Misinformation has gained attention within Vietnamese American communities as well as other immigrants and diaspora in recent years, spreading to a range of issues from the 2016 and 2020 US elections, the COVID-19 pandemic, and broader social issues such as affirmative action. Yet, prior research has overwhelmingly concentrated on English-speaking communities, leading to a lack of understanding on how misinformation spreads within and impacts immigrant communities. Understanding the flow of misinformation and its real-life impact requires deep attention to how online (mis)information is informed by, and often takes advantage of, the sociocultural histories of marginalized and immigrant communities.

Joining a growing effort within mis/disinformation work to better understand the spread of misinformation within diasporic communities, this paper makes use of focus groups with Vietnamese Americans across two generations and several geographic locations to examine the complexities of misinformation. We explore three research questions: 1) how Vietnamese Americans gather and share political information, 2) how community members assess trustworthiness in their political information and the barriers they face, and 3) the impacts of misinformation on political engagement and information seeking. Our findings highlight how intergenerational divides, lasting historical and political traumas of immigration, and language barriers shape the spread of misinformation and patterns of information seeking for Vietnamese Americans. Further, misinformation impacts political engagement at familial and community levels. These findings call attention to the need for researchers, policymakers, and community members to better attend to the inequities of information access and the vulnerabilities of immigrant communities as targets of misinformation.

Emphasizing a community-driven and participatory approach, the paper’s findings are based on insights from preliminary interviews with key informants—members of grassroots community organizations such as VietFactCheck, PIVOT, The Interpreter, messages from community members, and five focus group discussions conducted in Fall 2021. Each focus group included three to four participants, totaling 18, grouped together according to age similarity (18-24 and 50-75), political leaning, and language preference. Limited by self-selection, participants consisted of mostly first- and younger second-generation Vietnamese Americans. Most participants identified as politically left-leaning or independent. In future research, we seek to expand the study to include a more diverse set of participants in terms of political leaning and age groups.

Focus group transcripts were analyzed using an inductive thematic coding approach, conducted iteratively by the research team. The six emergent themes from the analysis are presented below: intergenerational divides, remnants of Cold War politics, historical trauma, power dimensions, language barriers, and political economy of technology.

Intergenerational divides

Focus group participants highlighted a disconnect of information and understanding about politics and current events between generations and attributed this difference to distinctly different information diets. Younger participants overwhelmingly reported using Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, general searches on Google, or mainstream media outlets like The Atlantic, New York Times, and NPR, to get news. On the other hand, senior participants reported a diverse roster of individual content creators and publishers: YouTube channels such as Dr Ngô Bá Định, Hoàng Bách, NVR by Lệ Ngọc, or newspapers such as CNN, Associated Press, Apple News, and “even Fox to be able to understand most sides” (Focus Group 1). While younger participants highlighted YouTube as the source of misinformation within their community, senior participants named specific publications and producers as major sources of political misinformation—i.e. Epoch Times, Washington Examiner, Fox News, NewsMax, One America News Network, Trần Nhật Phong, Ngụy Vũ (King Radio), etc. Concrete differences in information diets reduce opportunities for cross-generational discussions of news and current events and a lack of trust in the media consumed by other generations minimizes the potential for fact-checking and the disruption of misinformation.

Remnants of Cold War politics

Certain terms and phrases–e.g., “socialist,” “communist,” “relationships with China”—carry connotations and distinct historical significance to many early waves of Vietnamese American immigrants. Beliefs based on these understandings allow “sticky” misinformation narratives around candidates being “socialists”, or “tough on China,” or foreign interference in the U.S. election, to gain traction. A common pattern among first-generation Vietnamese Americans, as identified by younger participants, is a high level of patriotism toward the US, strong support for the military and police, and alignment with anti-communist rhetoric primarily coming from the Republican Party. Traditionally, Vietnamese Americans have voted Republican because “Reagan established himself as the leading authority on anti-communism” (Focus Group 4) which has since translated into an embrace of former President Trump. His anti-China, American exceptionalism rhetoric struck a chord with anti-communist Vietnamese Americans who believe “Trump will help Vietnam fight China” or that Trump will “destroy the Chinese Communist regime” (Focus Group 1). Further, some Vietnamese Americans are said to distrust liberal media “such as CNN, MSNBC or ABC” because they believe “leftist” outlets “advocated for the North Vietnamese Communists” during the war (Focus Group 3). Many participants point to a common pattern of information seeking among older community members, who gravitate toward Vietnamese language YouTube channels that broadcast news translated from right-wing English language media such as Breitbart, OAN, Fox News, or Epoch Times.

Historical Trauma

Migration experiences and trauma can deeply affect one’s political identity-making. Unaddressed memories of President Ford’s Republican administration “saving” Vietnamese refugees from communism and war (International Adoption, 2007; Zigler, 1976) as well as the resulting lingering traumas of these lived experiences (Mydans, 1992) allow space for false narratives–such as Biden being falsely accused of preventing refugee entry into the US (Viet Fact Check, 2020), to take hold among the community.

Senior generations of Vietnamese Americans hold lingering traumas from their past, while younger generations adopt such intergenerational grief and trauma. This manifests within the community as a desire to avoid conversations about political activities and social issues that also affect daily lives. Conversations involving subjects such as communism, China, patriotism, and the South Vietnam flag become sites for “emotionally taxing conversations with family members[. . .] to the point where I’m like it’s not worth it[. . .] we’ll be extra extra extra stressed all the time[. . .] and it doesn’t change their mind” (Focus Group 5). Participants attribute this avoidance of sociopolitical conversation as a core reason as to why misinformation spreads, and further exacerbates their historical distrust due to mainstream media sources having traditionally invisibilized the lived experiences of immigrant communities Power Dimensions.

Vietnamese Americans are a growing political power in the US and community members fear that misinformation could undermine efforts to increase political involvement and representation. Some expressed concerns that Vietnamese Americans could be a target for ideological disinformation, suggesting that problems of informational integrity online were exacerbated by state-run disinformation campaigns from Russia and China that are designed to undermine American political power. Older participants expressed concern that the Vietnamese government also engaged in information manipulation, which contributed to beliefs that online news and information in Vietnamese around American politics and the presidential election could not be trusted. Participants also questioned whether these (often pro-Trump or anti- communist) accounts could have been deployed or in some way supported by the Vietnamese government itself. This distills uncertainty amongst participants over the trustworthiness of the news their community consumed in Vietnamese, particularly news accessed via transnational social media sources.

Language Barriers

Misinformation continues to thrive on social media, in particular, because of lack of investment by social media platforms to properly undertake non-English language content moderation (Frenkel & Alba, 2021). Additionally, high translation costs and the closing of local media outlets result in authoritative Vietnamese language media becoming even less accessible. This has brought on the rise of Vietnamese language Youtube channels, which broadcast commentary and news without traditional commitments to journalistic integrity and fact checking protocols. Due to the inaccessibility of news in Vietnamese, several focus groups participants mentioned how they voluntarily translated articles from English to Vietnamese textually and posted it on Facebook or The Interpreter, a volunteer-run news aggregator site. They also verbally translated for their family members during discussions.

Political Economy of Technology

Participants also directed their concerns toward those intentionally spreading misinformation on social media, particularly YouTube, for financial gain. Participants explicitly named several YouTube and Facebook accounts that they believed spread political misinformation through sensationalized content that appealed to traditional Vietnamese values. Such accounts were seen as participating in the spread of misinformation in order to financially benefit from social media engagement. Further, our previous research into the spread of misinformation on Facebook (Nguyễn et al., 2022) highlights how social media platforms are not doing enough to slow the tide of misinformation in non-English languages. In prior research, the majority of Vietnamese-language posts within our dataset contained misinformation that has not been flagged with fact-check labels—yet the same narratives were labeled on English-language posts. Bridging these studies, we highlight how the political economy of social media platforms leads towards a polluted information environment for Vietnamese Americans as misinformation is profitable for creators and ill-addressed by platforms.

How do Vietnamese Americans find news they can trust?

Some community members were not only active consumers and sharers of political information, but also created their own political content in Vietnamese. For example, some partnered with translation organizations like The Interpreter, fact checking organizations like Viet Fact Check, or through personal blogs and social media pages. Participants believed this was useful as it provided access to political information in Vietnamese that was previously only available in English. However, the themes highlighted above similarly led to a lack of trust in information created and shared by community members—for instance, participants described a dismissal of translated fact checking they shared to their community or social circle as “communist “or from a “socialist organization” shutting down attempts at corrective conversations.

Overall, language barriers remain a persistent hurdle to finding trustworthy information. Older participants who were fluent in English gravitated toward mainstream media such as CNN or NPR. Similarly, those who relied on Vietnamese language outlets found news trustworthy if they could directly connect the information to mainstream media channels, though this was limited by a need for translation to bridge to mainstream sources. These factors emphasize the need to support local and ethnic media to mitigate the spread of misinformation.

Impact of Misinformation on Political and Civic Engagement

Rampant misinformation and suspected disinformation amplify preexisting beliefs and prejudice amongst older Vietnamese Americans. Of particular concern is how people came to support damaging policies and actions as a result of misinformation targeting specific narratives that would gain traction with the Vietnamese community. These include support for Trump’s anti-China rhetoric despite the ensuing rise in violence against Asian Americans which affected the Vietnamese community (Đan & Nguyen, 2021), misguided enthusiasm for the trade war with China regardless of cost (Silver et al., 2021), and the South Vietnamese flag being flown at the Capitol riot next to anti-Semitic banners and Confederate flags (A. Nguyen, 2021). As such, we call attention to how problematic information, its affinity to stoke historical traumas, and the political economy of technologies has structured the political actions of many Vietnamese Americans by promoting false narratives that take advantage of issues with historical significance and of emotional salience to the community.

The findings of this paper call to attention how misinformation impacts communities differently according to pre-existing power structures and information resources. For Vietnamese Americans, intergenerational divides in political information seeking, lasting historical and political traumas of immigration, and language barriers underpin the saliency and impact of misinformation. It affects political and civic engagement at both familial and community levels, highlighting the need for both academics and policymakers, in collaboration with community members, to better address the unequal access to information and to contend with the particularized complexities and vulnerabilities of historically marginalized immigrant communities as targets of mis/disinformation.

References

Đan, L., & Nguyen, L. (2021). Nyc’s Vietnamese community wary after anti-Asian incidents. VOA. https://www.voanews.com/a/usa_race-america_nycs-vietnamese-community-wary-after-anti- asian-incidents/6204013.html

Frenkel, S., & Alba, D. (2021). In India, Facebook grapples with an amplified version of its problems. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/23/technology/facebook-india-misinformation.html

International Adoption. (2007). Adoption History Project (AHP). https://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~adoption/topics/internationaladoption.htm

Mydans, S. (1992). Old soldiers: The last refugees free to leave Vietnam. The New York Times.

Nguyen, A. (2021). Exploring the political and cultural underpinnings of Vietnamese American conservatism. https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/26454

Nguyễn, S., Kuo, R., Reddi, M., Li, L., & Moran, R. E. (2022). Studying mis- and disinformation in Asian diasporic communities: The need for critical transnational research beyond anglocentrism. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-95

Silver, L., Devlin, K., & Huang, C. (2021). Most Americans support tough stance toward China on

human rights, economic issues. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. https://www. pewresearch.org/global/2021/03/04/most-americans-support-tough-stance-toward-china-on- human-rights-economic-issues/

Viet Fact Check. (2020). Did Joe Biden and democrats oppose Vietnamese refugees in the 1980s?. Viet Fact Check/Việt Kiểm Tin. https://vietfactcheck.org/2020/10/13/did-joe-biden-and-democrats- oppose-vietnamese-refugees-in-the-1980s/

You may like

-

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 20 – Democracy and Communism

-

A History of Legal Thought in Vietnam, 1945–1956 – Part 5: Ho Chi Minh’s Legal Thought after the Debate of 1948

-

In search of what I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải (Part 2)

-

In search of what I’ve lost: Essays by Nguyễn Khải

-

Interview with Father Le Ngoc Thanh: Faith can change the world.

-

Interview with Venerable Thich Khong Tanh: The tactics of the Vietnamese authorities on religion are: repression, division, isolation, and enticement

Translation: The Decision in 2013 of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Certain Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform

Thủ Đức Demonstration High School: A Modern Educational Policy and Teaching Method of the Republic of Vietnam

Southeast Asia falls into China’s Trans-Asian Railway Network

A Proposed Outline for a Study on Republicanism in Modern Vietnamese History

Tran Le Xuan – Diplomatic Letters

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years agoRethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

-

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education