Tuong Vu, University of Oregon

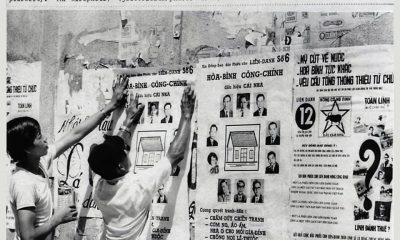

Speaking Out in Vietnam addresses an important phenomenon in Vietnamese politics and deserves to be widely read. The book follows Ben Kerkvliet’s influential approach to studying state-society relations in Vietnam, which is applied to a form of politics that is becoming more common during the last two decades in Vietnam. Although specifically focused on Vietnam, the book presents a convincing explanation for authoritarian resilience not only in Vietnam but also in China.

Speaking Out in Vietnam follows the rising public criticism of the Communist Party and the government (“Party-state”) and their reactions to this phenomenon for 10 years until 2015. Five clusters of questions guided the author’s data collection and analysis, including: “1) what are critics saying and what are their rationales and objectives; 2) who are the critics and what are their backgrounds; 3) to what extent do critics emphasizing one issue, such as Vietnam-China relations or land appropriations, interact and collaborate with critics stressing a different matter, such as workers’ conditions or democratization; 4) what are the reactions of party-state authorities and how does their behavior affect what critics say and do; and 5) what does the content, form, and range of public political criticisms and authorities’ actions reveal; about Vietnam’s political system?” (8)

Guided by the above questions, the book devotes four chapters to four kinds of regime critics with distinct demands: striking factory workers who demanded better wages and working conditions; villagers protesting against corruption and land appropriations; citizens who demonstrated against China and Vietnamese government’s perceived weak reactions to defend sovereignty; and dissidents who advocated the democratization of the political system.

Based on his data, Kerkvliet argues that terms such as responsive authoritarianism and market Leninism that have been used to call Vietnam’s (or China’s) political system fail to capture interactions between rulers and the ruled. His preferred “summary label” is a “responsive-repressive party-state” system in which there is room for citizens to advocate changes, criticize policies, and even resist certain government actions. In this system, the government often listens, responds, and accepts citizens’ concerns while sometimes repressing certain groups or individuals. The existence of such space for criticisms (however manipulated and circumscribed) and the authorities’ responsiveness, as Kerkvliet argues, “help account for the durability of the regimes in Vietnam and China” (5).

An important finding of the book is that the political criticisms and activities of workers, villagers, protesters, and dissidents evolved independently from each other. With the partial exception of anti-China protesters and regime change advocates, there has been scarce coordination or mutual support among regime critics, in part because the party-state “stifled such interactions” (142). The ability of the party-state to do so also explains the regime’s durability. As Kerkvliet observes, “anathema to party-state officials will be collaboration among groups formed around separate issues… [The officials] will remain highly vigilant to avoid waves of political discontent about distinct issues from merging to become a torrential storm threatening the regime” (143).

Kerkvliet’s emphasis in the book is on “interactions” rather than on the causes of criticisms and protests per se. Readers do not get a sense of whether government officials or deeper problems in the political system caused popular grievances. The analysis is focused on the act of voicing criticisms and how the authorities responded. For instance, although the book shows that the authorities often took the side of workers after strikes had broken out, it is unclear whether and to what extent government policies and complicit officials (such as the legal ban on independent trade unions or union cadres’ failure to protect workers) had caused the strikes in the first place. In conclusion, however, Kerkvliet hints at the causes of those grievances: “We can recognize that … authorities [listened and responded] positively to people’s concerns while at the same time acknowledge that [they] often act without input from citizens and frequently dismiss, even repress citizens’ criticisms and protests…” (146).

Despite such attitudes and actions from the party-state, Kerkvliet points out that Vietnam is not heading for democratization in the near future for several reasons, including the unity of party-state leaders to resist political reforms as well as low internal and external pressure for doing so. Barring a major collapse of the national economy that would raise internal pressure, “the political system can continue in the same direction as it has been going in recent decades, evolving more elaborate and public dialogical interactions … without changing the regime” (147). The book stops in 2015, but events since 2016 during the second term of Party chief Mr. Nguyen Phu Trong suggests 1) much greater elite disunity exists; 2) corruption and abuse of power are stirring up louder demands for change; and 3) repression appears rising at the expense of responsiveness. One thus wonders whether Kerkvliet should revise his prediction to take into account recent developments.

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

ARCHIVES4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years ago