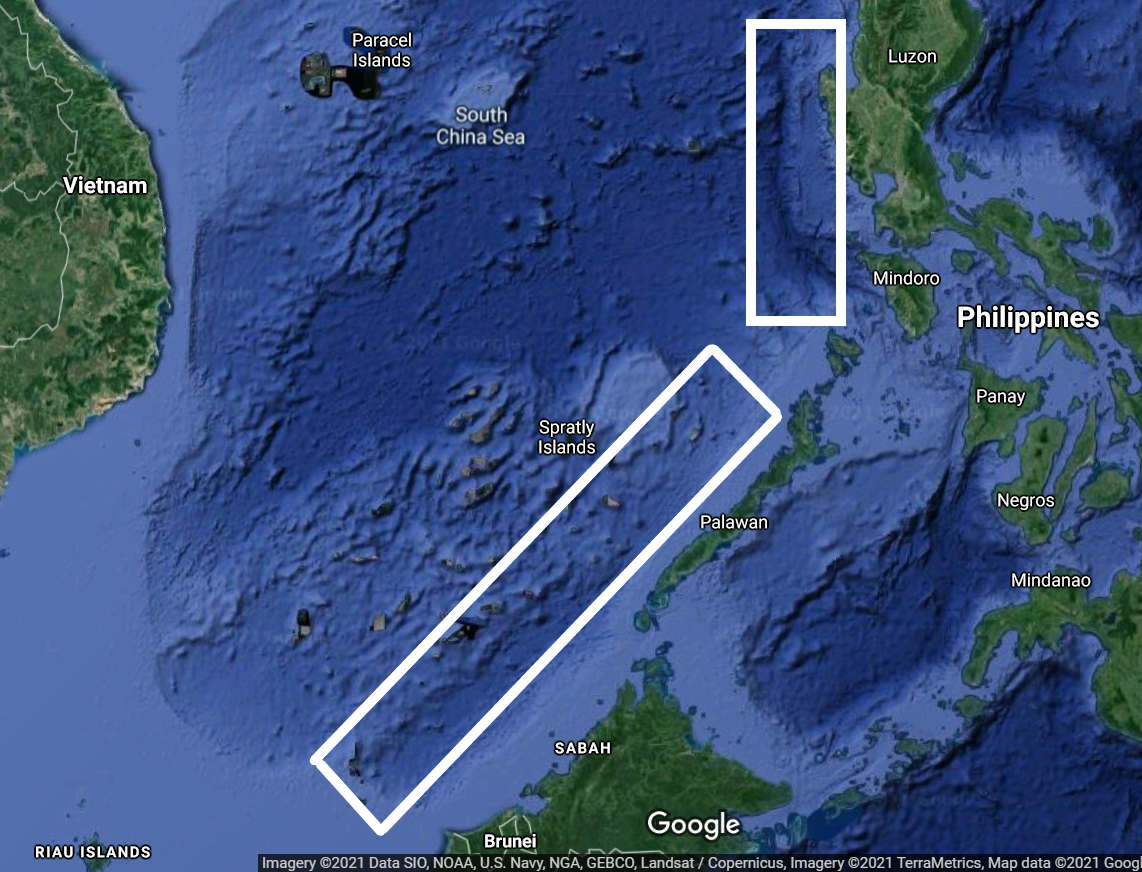

(The isobath lines between the Spratlys and Malaysia’s Sabah state, and Philippines’ Palawan and Luzon islands)

Nguyen Luong Hai Khoi

On December 12, 2019, Malaysia submitted to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) a claim on an extended continental shelf (ECS) beyond 200 nautical miles from the baseline. Malaysia filed a claim for an extended continental shelf with Vietnam in 2009. Why did Malaysia relaunch a claim for interests in the South China Sea, although China would object?

In 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) ruling in the Philippines v.s China case created a legal condition rejecting the grounds that China and the Philippines used to protest the joint submission of Vietnam and Malaysia in 2009.

From 2009 to 2011, the Philippines protested the Joint Submission by Vietnam and Malaysia and protested China’s notes to claim its sea territory, extended continental shelf, and sovereignty over the Kalayaan Island Group (western part of the Spratlys). On the Joint Submission of Malaysia and Vietnam, The Philippines argued that this Joint Submission claims an extended continental shelf that overlapped with that of the Philippines and created “the controversy arising from the territorial claims.” On the Chinese notes, the Philippines’ argument has three points:

- The Kalayaan Island Group constitutes an integral part of the Philippines.

- Because of the principle of “the land dominates the sea,” the Philippines has the right to exercise sovereignty and jurisdiction over the waters around the geological feature in the Kalayaan Island Group.

- Concerning this area, sovereignty, and jurisdiction or sovereignty rights, as the case may be, necessarily appertain or belong to the appropriate coastal or archipelagic state – the Philippines – to which these bodies of waters, as well as seabed and subsoil, are appurtenant, either in the nature of Territorial Sea, or 200 M Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), or Continental Shelf (CS) under Article 3,4,55,57, and 76 of UNCLOS.

The Tribunal Award of 2016 (the Philippines vs. China) invalidates China and the Philippines’ legal bases. First, Chinese U-shaped lines are not legally valid. Second, Spratlys are not qualified as “islands,” so they do not have neither their continental shelf nor are they valid to be applied to the principle “the land dominates the sea,” as the Philippines argued in 2011.

Therefore, we can understand why Malaysia reactivated the 2009’s submission. In 2009, China and the Philippines protested against Vietnam and Malaysia. CLCS has no authority to consider submissions that are opposed by third parties. The Tribunal Award of 2016 provides a legal ground so that Malaysia can raise a problem: If false arguments protest submissions, CLCS should consider such submission again.

In addition to the legal condition, international relations between China and the West were also factors in Malaysia’s surprising submission.

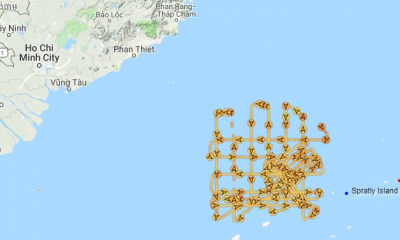

Furthermore, from July to October 2019, China had conducted a campaign to intrude the continental shelf and exclusive economic zone of Southeast Asian countries in the South China Sea, including Malaysia, the Philippines, and especially Vietnam. This China’s incursion is a dangerous and aggressive escalation that seriously violated UNCLOS.

As mentioned above, the Malaysian Submission in December 2019 provoked a series of exchanges of diplomatic notes among countries for the first time, most of which opposed the Chinese aggressive attitude and violation of international law. These note exchanges have also exploded as Western and Asian countries agree on perceptions of “Chinese threats,” as US-China relations have become tenser than ever due to the competition between the two superpowers for a global leadership position.

Malaysian submission was sent to the Commission on December 12, 2019, while phase one negotiation between the US and China over the trade war was coming to an end and was about to sign officially. Although the US and Europe’s disputes because of Trump’s “American first” policy and different approaches towards China, they shared a common view of “Chinese threats.”

Malaysia did not expect that ten days later, the Covid-19 pandemic broke out in China and spread around the world. The way China responded to Covid-19 made the world no longer hesitate to speak frankly about Chinese threats. In the summer of 2020, China had intensified its aggressive activities in the South China Sea. As a result, a series of notes were sent to the UN to protest Chinese illegal and fierce attitudes.

The possibilities of negotiation in the future

The extended continental shelf claimed by Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines in submissions made in 2009 and 2019 are overlapped with each other. In 2009, Vietnam’s claim for an extended continental shelf from the baseline of the central coast also overlapped with the Philippines’ extended continental shelf from the baseline of Palawan. The extended continental shelf claimed by Malaysia in 2019 also overlaps with that of the Philippines (from Palawan islands’ baseline) and Vietnam (from Vietnam’s southwestern baseline.)

All countries in the South China Sea, except China, are open to negotiating based on UNCLOS and the Rules of Procedure of CLCS. In the note protesting Vietnam in 2009, the Philippines also suggested discussing and resolving the disputes. In 2019’s submission, Malaysia also stated that “there are areas of possible overlapping entitlements in respect of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm of the area of the subject of this Partial Submission.” (4.2, p.2). That Vietnam and Malaysia submitted a joint submission in 2009 is an encouraging example. Nguyen Hong Thao, a professor of the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam, in an article on the Diplomat optimistically said that “the Philippines may join with Vietnam and Malaysia in submitting tripartite submission on the ECS beyond 200 nm in the future.”

To negotiate legally and scientifically, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam have to do scientific surveys for seabed geology in some areas. If the actual continental shelf is more than 200 nautical miles, a coastal state can extend its continental shelf to a maximum of 350 nautical miles. The Philippines’ 350 nautical miles from the baselines is overlapped with that of Vietnam.

There are two deep isobath lines that run close along the Philippines’ Luzon island and Palawan island, and one deep isobath line running close along with Malaysia’s Sabah state. These isobaths’ exact depths are unknown. Therefore, there are many stages to go through to negotiate between Southeast Asian countries in the South China Sea to achieve fairness for each country and prevent China’s illegal claims.

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago