By Trùng Dương

After the fateful April 30, 1975, several South Vietnamese were bitter for having been abandoned by the United States. A medical doctor, with whose family I and my two small children shared a tent at Camp Pendleton, Calif., was applying to go to France or Canada. He could not bring himself to live in America because he felt betrayed. We lost track of each other after leaving the refugee camp. I did not know where his family finally resettled.

Who-lost-Vietnam was the question of those chaotic and tragic days. Whoever did depends on one’s political view. The way I was raised, however, is, when something terribly happened that turned your life up side down, to look inside yourself first. And I did look inside myself as well as the soul of my beloved southern land where I grew up since my parents took us 11 children to this newly-created free nation in 1954, helped enthusiastically by the world’s most powerful country of the United States of America and its allies of the free world. Sure, the United States had no doubt viewed SVN as the “last frontier” against the red tide then. But to the South Vietnamese, it was the precious opportunity to build their first truly free and democratic society after thousands of years living under either an absolute monarchy or foreign domination. They didn’t take the young republican state lightly.

Somehow we had squandered the opportunity. Sure, no doubt there are a host of other reasons as well that have been reviewed elsewhere, no need to repeat here. After 20 years of nation building amidst political turmoil and a bloody war that took millions of lives and tremendous destructions, many of us, including myself, then a 30-year-old war widow with two small children, ages 2 and 9, became political refugees for the second time. Hundreds of thousands who couldn’t make it out in mid-1975 when the communists took over South Vietnam risked their lives escaping via the seas or jungles. Thousands lost their lives at seas. Meanwhile, thousands more including several writers, artists and journalists, were lured into the so-called re-education camps throughout Vietnam. Many had perished there.

President Kennedy once said, “Victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan.” South Vietnamese, either exiled or still in Vietnam, both became “orphans.” For decades we lived in silence, misunderstood and humiliated, trying to rebuild our lives in our adopted lands. In spare times and on weekends, some of us have been trying to regroup, some engaging in political activities working for a more liberal Vietnam, others in preserving our history and culture, which the new regime was trying to erase and replace with the foreign ideology of communism, completely alien to, if not rejected by the people if given a chance. Efforts in the latter are sporadic, piecemeal, and mainly privately funded, but abundant nevertheless in the forms of printed publications and oral histories. Since the birth of the Internet 25 years ago, these materials have found a sanctuary and further blossomed. They are, however, mostly in Vietnamese and thus mainly inaccessible to non-Vietnamese speaking audience, including the second and third generations of Vietnamese overseas, many of whom have limited to no language ability.

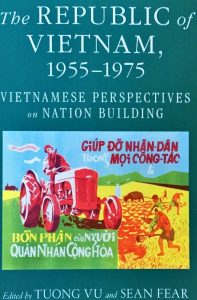

I am pleased to know the collection “The Republic of Vietnam, 1955-1975 – Vietnamese Perspectives on Nation Building,” published by Cornell University Press’s Southeast Asia Program Publications, has finally come in to fill the gap and to, hopefully, serve as foundation for further studies of a subject that still remains sadly, if not biasedly, unexplored. Edited by Tuong Vu, associate professor of Political Science at the University of Oregon, and Sean Fear, a lecturer in International History at the University of Leeds, England, the 200-page volume is a compilation of the papers presented at the Symposium Nation-Building in War: The Experience of Republican Vietnam, 1955-1975, taken place in October 2016 at University of California in Berkeley.(*)

The collection’s cover

These papers, by former South Vietnamese officials, teachers, soldiers, journalists, and artists, take the audience through their experiences in the building of the new nation of Republic of Vietnam “as a passionately imagined nation in the minds of ordinary Vietnamese rather than merely as an expeditious political construct of the U.S. government,” as stated by the editors. They provide testimonies of war, politics, economics and everyday life of people from many walks of life during the turbulent years of the Second Republic, embroiled in what Americans generally call the Vietnam War. Unlike the popular, if not from a mindset, belief reflecting the then communist propaganda of the RVN as an American “puppet,” the collection “reveals that the conflict in Vietnam was a true ideological divide between the communist north and the noncommunist South and not just a proxy struggle of the Cold War,” according to the editors.

Having had the opportunity to read some of the papers in manuscript format and attended the two-day symposium more than two years ago, I still felt touched contemplating the collection’s green, red and yellow cover adorned with a vivid image of soldiers helping farmers in rice fields, of which the drawing style looks so familiar to me growing up in the South and having seen such similarity everywhere – on billboards, posters, flyers, postal stamps, book covers and even music sheets. The artistic style had imprinted in my fresh mind of an art student then.(**)

I have to admit that up until recently, my memory about our nation building odessey focused mostly around the field I know best, that is arts and letters. I am always amazed, and proud as well, for the achievements, within just 20 years, by SVN writers, journalists and artists. Thanks to a relatively liberal environment and a sense of mission in preserving our literary heritage destroyed by the communist North, these individuals, including several emigrants from the North, collectively or individually rebuilt, enriched, promulgated their works while inspiring one another. The artistic blossoming era is vividly described by writer Nhã Ca, a presenter at the symposium, whose paper I had the pleasure to translate (pp. 155-163). Despite the communist efforts following the takeover of the South in condemning, confiscating and burning millions of books, music tapes and artworks, these materials survived, especially now with the Internet technology. They have also been sought after by younger generations in Vietnam as well.

The collection “Vietnamese Perspectives on Nation Building” has provided me with a more comprehensive view of the developments and achievements in other aspects within the big picture of SVN’s nation building experience. One could hardly imagine all these took place within a mere 20 years, five years fewer than the required age of a generation, and most of all, despite the ravaging war.

Divided into five themes – economic development, politics and security, education, journalism and media, and culture and the arts – the volume takes the reader through a sweeping, information-packed journey presented by more than a dozen speakers. In the area of economic development (Chapter 1-4, covering banking, finance and economic development), former minister of trade and industry Nguyễn Đức Cường, law professor Vũ Quốc Thúc, former minister of economy during the Second Republic Phạm Kim Ngọc, and former minister of agriculture and land reform Cao Văn Thân share their experiences in getting the young nation up and running either during the turbulent transition from colonial time under the First Republic (1955-1963) or amidst a horrific war during the Second Republic (1967-1975). One of my favorite articles is Cao Văn Thân’s detailed presentation about agricultural modernization and the 1970 Land to the Tiller land-reform program, about which I have limited knowledge. Why didn’t I know more about this important campaign, I wonder. The irony is we knew more about the bloody land reforms carried out by the communist North in the early-1950s than the rather inspiring and successful Land-to-the-Tiller program in the South during the early 1970s, buying up lands from wealthy landowners to distribute and deed to small farmers.

In the area of politics and security (Chapter 5-7), former press secretary Hoàng Đức Nhã shares his work during the negotiations that led to the 1973 Paris Agreements, which sadly helped seal the fate of the South. Former colonel and head of the National Police Academy Trần Minh Công discusses the challenges of keeping security during a period of political unrest and guerrilla insurgency. And, in closing this subject area, former lieutenant colonel Bùi Quyền offers his reflections of a frontline soldier, his assessment of the SVN military, and experience with working with American advisors.

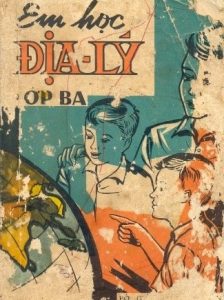

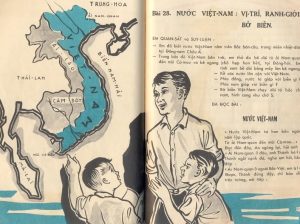

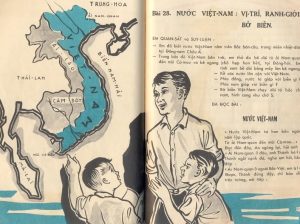

Another revealing and fascinating subject is the area of education (Chapter 8-9), presented by two teachers and school administrators during the Second Republic, Nguyễn Hữu Phước and Võ Kim Sơn. While Nguyễn Hữu Phước explores topics such as the philosophical tenets – humanism, nationalism, and liberalism – as foundation for the educational system, the development of a comprehensive high school, community colleges, and teacher training programs; Võ Kim Sơn shares her personal involvement in various institutions including the National Wards Schools (Quốc gia Nghĩa tử), College of Education in Saigon University, and the private Catholic School Thánh Mẫu in Gia Định Province. All those educational developments and progresses, assisted by various American universities in contracts with the U.S. government, have no doubt lifted the South from nearly a century of colonialism and limited opportunities onto the road of progress and prosperity that had it not for the war and the final communist victory, Vietnam would have been on a much different trajectory. The Republic’s educational heritage has, nevertheless, persisted – virtually, that is – and has become a source of inspiration, if not nostalgia for those in Vietnam. One such longing is reflected in a well-documented article by blogger Huỳnh Minh Tú, which has been reposted on several Web sites, is titled “The Republic of Vietnam’s educational system: a forever regret.”(***)

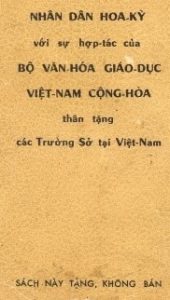

(A book on geography for third grade, published by the Ministry of Education, circa the First Republic. Left, the book cover; center, two inside pages; and right, back cover, which reads, “The American People in Collaboration with the Ministry of Culture and Education of the Republic of Vietnam, gifted to the schools in Vietnam,” and at the bottom “This book is a gift, not for sale.”)

Three journalists, Phạm Trần, Vũ Thanh Thủy and Trùng Dương, offer their experiences in the collection’s fourth part (Chapters 10-13). While Phạm Trần describes the general environment in which the mostly privately-funded press – a characteristic of the South’s press that does not exist in the communist system – operated, and Trùng Dương offers the view of the press as a government watchdog and defender of the public right to be informed, Vũ Thanh Thủy share her special, if not unique experience as a woman war correspondent.

In Chapters 14 and 15, writer Nhã Ca, author of “A Mourning Band for Hue” and several novels, describes a SVN during the uniquely historic blossoming period of the arts and letters; followed by actress Kieu Chinh with her memoir of the development of the new nation’s movie industry.

And finally, in closing the book, Nu-Anh Tran, assistant professor at the University of Connecticut, and Tuan Hoang, assistant professor at Pepperdine University, explore in Chapters 15 and 16 the need for more personal stories from elder South Vietnamese to add to the American historical memory.

In compiling the collection, the editors wish to bring forward the often ignored deep root of the Vietnam War, that is the ideological struggle between the communist North and the republican constitutionalism advocated by SVN’s diverse political groups, an aspiration that emerged as early as during the early colonial era and reflected through the perspectives of the collection authors. Unlike the popular belief that SVN was but a shadow to the Americans as reflected prominently in the media and adopted by many in the academia, the Vietnam War was “[N]o mere Cold War proxy struggle, the communist/republican schism in Vietnam was irreconcilable long before American intervention began in earnest, and it lingers among Vietnamese across the globe even today,” state the collection editors in the introduction.

“Given the deep historical and ideological roots of the civil war in Vietnam, and the critical role played by South Vietnamese actors in shaping its outcome,” the editors conclude, “it is no longer possible to ignore the impact of Vietnam’s republican heritage to the origins and the outcome of the war.”

As I review “The Republic of Vietnam, 1955-1975 – Vietnamese Perspectives on Nation Building” in pandemic lockdown, the invisible and lethal Covid-19 has been raging all over the world, upending everyone’s life, forcing us to rethink about a host of historical, political, social, international and environmental issues and requiring us to change ourselves if we will ever survive. I couldn’t help seeing life matters as something not set in stone as we like to think and aspire to hold dear due to a sense of insecurity. In a few days, Vietnamese overseas will also commemorate the 45th anniversary of the demise of South Vietnam that physically wiped out a young and free nation though not its heritage. I wish we will be able look at our world with a more open mind.

This volume is available on Amazon.com and at the Cornell University Press’s Web site at cornellpress.cornell.edu, at $24.95. A Vietnamese version of the collection will be released by the end of this year, according to the collection’s co-editor Tuong Vu.

[TD 2020/04]

Notes:

(*) For the coverage of the symposium, please see a 2-part report (in Vietnamese) by Trùng Dương: UC Berkeley Nhìn Lại 20 Năm VNCH Xây Dựng Quốc Gia Trong Thời Chiến- Kỳ 1/2, (See Da Màu November 9, 2016 and Da Màu November 10, 2016)

(**) “Họa sĩ Duy Liêm – Tác giả của những bìa tờ nhạc vàng nổi tiếng,”

(***) Huỳnh Minh Tú, “Nhìn lại nền Giáo dục VNCH: Sự tiếc nuối vô bờ bến,”

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Politics & Economy1 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago