Editor’s Note: The following is a translation by our editor Vinh Phu Pham. The original piece can be found here.

Anh Nguyễn

Phan Khôi is a modern cultural figure of Vietnam, as honored by the Phan Chau Trinh Cultural Foundation in 2017. However, due to historical reasons (The Nhân Văn-Giai Phẩm affair), it wasn’t until 1991 that Phan Khôi was officially mentioned in the Dictionary of Vietnamese Historical Figures published by Nguyen Q Thang and Nguyen Ba The from the Social Sciences Publishing House. By then, 32 years had passed since Phan Khôi’s passing in 1959, and during this time, his name and works were hardly mentioned in Vietnam due to the sensitive nature of the times.

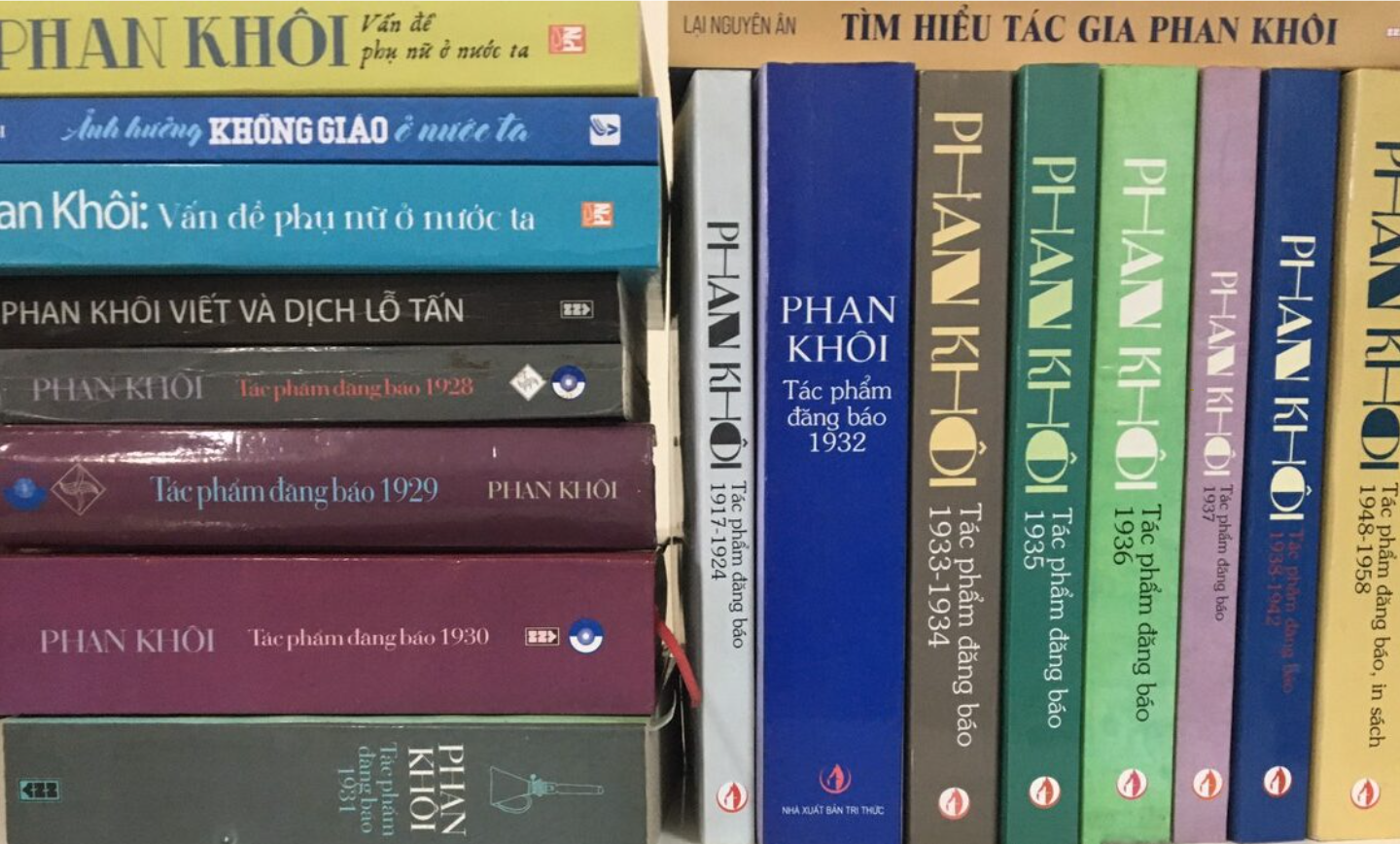

Starting from this point onward, researchers, journalists, and Phan Khôi’s descendants have gradually contributed to the introduction, analysis, and evaluation of Phan Khôi’s works and ideas across various fields in which he was involved, such as journalism, literature, translation, Vietnamese linguistics, proficiency in Chinese studies, and more. Notable among these works are the memoirs and notes compiled by his youngest son, Phan An Sa (published from 2013 to 2021); the book series “The Works of Phan Khôi – Read and Reflect” (published in 2017) by one of his distant relatives, Professor Doctor Ngô Quang Huy; and especially the research on Phan Khôi by the scholar Lại Nguyên Ân (comprising 16 books published from 2003 to 2023).

Recreating the multi-faceted and rich portrait of the cultural figure Phan Khôi

Lại Nguyên Ân devoted 27 years of his life to this significant project. To date, he is one of the very few social science researchers in Vietnam who have focused extensively on a single author. His focus was on Phan Khôi, while the other researcher was Professor Historian Chương Thâu, who specialized in studying Phan Bội Châu.

Lại Nguyên Ân’s research on Phan Khôi can be divided into two parts. The first part consists of 12 thick volumes totaling 7617 pages, which meticulously collect, classify, arrange, and annotate all of Phan Khôi’s published works from 1917 to 1957.

This part is crucial as it forms the foundation for comprehensive and in-depth studies of Phan Khôi. This is because aside from the 3 published books of Phan Khôi, namely “Chương Dân Thi Thoại” in 1936; “Việt Ngữ Nghiên Cứu” in 1955; and the novel “Trở Vỏ Lửa Ra” in 1939, all his other works were in the form of newspaper articles. Without these 12 volumes compiling Phan Khôi’s newspaper articles, it would be extremely difficult to fully grasp the complete portrait of this cultural figure.

The second part comprises four specialized books on Phan Khôi. The first is “Phan Khôi’s Writings and Translations” by Lỗ Tấn (2007); “Phan Khôi and the Issue of Women in Our Country” (published in 2016, reprinted in 2018); “Phan Khôi: Influence of Confucianism in Our Country” (2018); and the latest book, “Understanding the Author Phan Khôi” (2023). These four volumes total 2277 pages. Among them, “Understanding the Author Phan Khôi” can be seen as a summary of everything Lại Nguyên Ân dedicated 27 years of his life to researching about this figure.

A preliminary summary by author Phan An Sa shows that the rich heritage of Phan Khôi’s works, compiled by Lại Nguyên Ân, includes over 700 essays, nearly 1200 short stories, more than 40 poetic works, novels, short stories, memoirs, and reflections, over 40 translated works, and 400 standalone articles in various sections or other newspapers.

From Lại Nguyên Ân’s work, readers can envision a comprehensive portrait of Phan Khôi. His most pivotal role was as an intellectual critic and one of the most prominent critical voices in Vietnam during his time. Following this, along with great scholars like Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh, Phạm Quỳnh, Nguyễn Văn Tố, Trần Trọng Kim, Huỳnh Thúc Kháng… he contributed to shaping Vietnam’s contemporary cultural landscape. Finally, Phan Khôi always chose a progressive and innovative approach in all the fields he addressed.

This role as an intellectual critic led him to confront Colonialism from 1928-1940 when he courageously defended members of the National Party, the Revolutionary Youth League (who were being pursued and sentenced by the colonial authorities). According to Lại Nguyên Ân, Phan Khôi demanded that the members of these organizations, when arrested, should be tried in the French courts instead of the Southern Court (under the Hue Court, governed by the laws of Gia Long, which would impose severe penalties). He also criticized the Nam Ky Constitutional Party, whose many members were councilors in the province and city councils, for remaining silent when the colonial authorities suppressed public demonstrations with firearms. He also wrote numerous commentaries, criticizing the backwardness of the imperial bureaucracy, the corruption in the political circles during the years 1935-1936 when he was the editor-in-chief of Tràng An newspaper in Huế. He also engaged in debates with literary and artistic leaders of Vietnam in the post-1954 era.

Playing the role of a critic, Phan Khôi initiated numerous debates and even revolutions in many fields through the press. For instance, he opened a discussion on historiography in 1928 in Đông Pháp Thời, on the issue of whether or not the people of Annam (Vietnam) should invite the French to protect them; he initiated the idea of the National History Competition in the Thần Chung newspaper in 1929 and contributed numerous articles to this competition; in 1932, he launched the New Poetry Movement; Phan Khôi engaged in debates with Trần Trọng Kim on history, debates on the Tale of Kieu, debates on Buddhism with the monk Thiện Chiếu, and against the dogmatic scholars…

Meanwhile, as one of the architects of contemporary culture, Phan Khôi clearly expressed progressive thoughts. He highlighted the heavy influence of Confucianism in Vietnamese feudal society with its negative consequences in the modern era. Therefore, the Vietnamese solution was, in terms of theory, to transform Confucianism from a guiding principle to an object of study, analysis, and criticism, while still retaining its essential, beautiful aspects such as patriotism, integrity, and contributing to the construction of character… At the same time, he emphasized the fundamental issues of Western civilization that Vietnam needed to learn from, such as personal values and democratic values. As Lại Nguyên Ân observed, “Phan Khôi was keenly aware of the changing cultural landscape when Confucian society in Asia accepted Western ‘civilizing’ influences…He regarded Western civilization, particularly European and American, as the newest civilization of contemporary humanity, with its scientific, democratic, and free characteristics, as representative of the progressive trend of the modern era.” Therefore, Phan Khôi volunteered to be “a small vanguard of the common intellectual army, paving the way forward.” From this, he initiated movements in many newspapers where he was the editor-in-chief, supporting women and becoming one of the most active advocates of women’s rights in Vietnam in the 1930s.

Lại Nguyên Ân came to a quite reasonable conclusion about the character he painstakingly researched: “It can be said that Phan Khôi is the clearest and most successful representative of the modernization ideology of Phan Chu Trinh in life, but unlike his predecessor, Phan Khôi completely did not present himself as a politician; he lived as an ordinary person in daily life, only acting professionally as a rhetorician, impacting society through rhetoric. Phan Khôi belongs among the leading intellectuals who contributed to creating the intellectual and cultural landscape for Vietnamese society in the early 20th century, but alongside luminaries like Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh, Phạm Quỳnh, Trần Trọng Kim, Huỳnh Thúc Kháng…, he often presented himself as a critic, and his criticism often brought new depth to knowledge.”

(Portrait of the researcher Lại Nguyên Ân)

The meticulousness of a research project with local specificities

To complete the research project on Phan Khôi, Lại Nguyên Ân had to dedicate his heart and soul to studying the author Phan Khôi under extremely unique conditions, which would be difficult for social science and humanities researchers worldwide to imagine.

According to international norms, for a cultural figure like Phan Khôi and a vast body of work requiring collection, selection, organization, and study such as this, it would become a major cultural project of a university, a province, or a nation, with the leadership of Lại Nguyên Ân accompanied by many graduate students participating. This project would receive millions of USD in funding to have enough human resources, materials, and infrastructure to carry it out to the best of its ability. Even after completion, it could be published both domestically and internationally. It could become a topic for young researchers to successfully defend their doctoral dissertations.

However, in Vietnam, this project was mainly driven by the passion and love of Lại Nguyên Ân. He had to fund everything from A to Z himself and struggle to solve difficult problems due to the poverty of our outdated research libraries. While the digitization of libraries remained very slow. And the documents in Vietnamese newspapers from 1917 until now were mostly worn out and deteriorated. Therefore, the work began with arduous journeys such as finding all the old newspapers (some of which might have been missing), then reading through all of them to find each of Phan Khôi’s articles (some of which were not under his real name, and some were under various pen names). While Phan Khôi wrote for 33 different newspapers, magazines, and specialized books, averaging around 1000 pages per year. Trying to find everything needed was extremely difficult.

Next, he hired typists or had to personally struggle to type. After that, he categorized, organized, studied, and extracted useful ideas. At the same time, he had to complete all the work assigned at his workplace, where he was earning a living as an editor of a publishing house, and take care of his family like an ordinary father.

Moreover, Lại Nguyên Ân had to fight tooth and nail to find solutions to help each book find a place for funding printing and distribution. Although a few initial volumes were included in the orders of the Da Nang Publishing House, it became increasingly difficult later on. This was because these were useful books for sustainable academic research but lacked market appeal. Since 1992, when he started this project until now, best-selling books have been favored by bookstores.

Meanwhile, Phan Khôi was a controversial figure for many years. And Phan Khôi’s reputation plummeted after the Humanism Scandal in 1957. Therefore, for about 40 years after that, few openly cared, researched, or wrote about him, both in academic circles and among ordinary readers. As time went on, information about him sank further. Witnesses who knew about Phan Khôi passed away one after another, and the books and articles of Phan Khôi could be completely damaged if they were unfortunate enough to be affected by natural disasters or simply decayed due to humidity in Vietnam.

In this context, Lại Nguyên Ân’s work was somewhat akin to Don Quixote tilting at windmills.

Fortunately, many respected his efforts and wholeheartedly supported him. Dozens of friends, researchers, relatives of Phan Khôi’s family, book writers, publishers, and the Toyota Cultural Foundation supported and encouraged him a lot for a while.

And more importantly, Lại Nguyên Ân worked tirelessly without counting, because he loved Phan Khôi too much, wanting to be a pioneer in seeking out values and proposing useful research ideas about this cultural figure.

But the good thing was that when Lại Nguyên Ân just opened one door, then many other doors were subsequently opened.

He had dived countless times over several decades at the National Library of Vietnam (while contact with old books and newspapers was very harmful to someone suffering from asthma like him). He also once traveled to the United States for a month with the help of the researcher couple, Professor of History Peter Zinoman, to read and photocopy valuable materials on French books and newspapers about Vietnam at the libraries of the University of Berkeley in California, as well as at the Cornell University Library in New York state. He returned home with dozens of A4 paper boxes of photocopies. He was also helped by literary critic Thụy Khuê in France with some other materials.

Meanwhile, Lại Nguyên Ân also said he carefully read the works of scholars from the South, those who had gone before him in researching Phan Khôi such as Nguyễn Văn Trung, Thanh Lãng, Bằng Giang, Vu Gia, Nguyễn Q Thắng. He also didn’t miss what contemporary scholars were publishing both domestically and internationally. He believed this was “almost like a relay race” because he received from here suggestions about literary history, signals about values that the public was ready to accept and cherish about Phan Khôi, despite the hurdles due to the tragedies that befell the life of this cultural figure.

Dr. Peter Zinoman, Professor of History and Chair of the History Department at the University of California at Berkeley, USA, commented: “Lại Nguyên Ân has accomplished a truly monumental work in terms of scholarship, literature, and history.”

Zinoman highly praised Lại Nguyên Ân in three aspects. Firstly, the meticulousness in finding documents and studying for 27 years in the impoverished conditions of research libraries in Vietnam and the slow progress in digitizing scattered collections of Vietnamese newspapers. Secondly, Lại Nguyên Ân completed this project almost without any institutional support (such as funding typically obtained through collaborations with scientific research institutes or specialized departments of universities in Vietnam). And thirdly, the long-standing political sensitivity surrounding the phenomenon of Phan Khôi. When Phan Khôi’s reputation plummeted after the Humanism Scandal at the end of the 1950s and remained a taboo topic for 40 years afterward. This meant that there was no rich collection of writings and research about Phan Khôi for Lại Nguyên Ân to rely on.

Therefore, Zinoman affirmed: “Lại Nguyên Ân is truly a pioneer in the topic of Phan Khôi. With unmatched determination and resilience, with wisdom combined with a deep progressive sense, he has completed this monumental project.”

Lại Nguyên Ân is 79 years old this year, from Hà Nam province, a province in the Red River Delta region of Vietnam. He graduated from the University of General Education in Hanoi with a degree in linguistics in 1968. Upon graduation, he began his career as a teacher at a secondary school. It wasn’t until 1977 that he was transferred to work as an editor for the New Works Publishing House. He taught himself to become a literary researcher. The virtues of modesty, caution, diligence, and meticulousness made him “able to pursue great goals for a long time at a high speed,” as revealed by researcher Vương Trí Nhàn.

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago