Kevin Pham

Recent polls show that U.S. national pride is at its lowest in two decades of Gallup measurement. National shame is overtaking national pride, and this is no surprise. At the moment, we have the highest number of coronavirus cases and deaths in the world, especially humiliating when compared to how some developing countries (like Vietnam) have responded to the pandemic. The American passport, once powerful and allowing Americans access to most of the world, has lost its worth as Americans are now banned from most of the world. There are other sources of national shame as well. The U.S. is at its highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression. Non-Black Americans are gaining more awareness of anti-Blackness and racialized police violence. Adding to the shame is economic inequality, lack of health care for millions, anti-intellectualism, and lack of moral leadership. The stature of the U.S. is declining in our eyes and the eyes of the world.

Shame—a painful feeling of humiliation that makes one want to hide from others—can be debilitating, leading one to despair and self-abandonment. Americans who feel too much national shame may want to flee to other countries. We might see ‘brain drain.’

The challenges we face are difficult, particularly for our youth, but we need thoughtful Americans to stay and work to improve our country. The problem, however, is that doing so would be difficult if we have little pride to begin with. The American philosopher, Richard Rorty, argued that “national pride is to countries what self-respect is to individuals: a necessary precondition for improvement.”[1] National shame, Rorty argues, can “make energetic and effective debate about national policy unlikely.”

The kind of national shame matters, too. In the past, American national shame primarily came from the shame of having harmed others. Rorty argued that the cultural left in the United States has been unfortunately mired in this kind of shame. They found pride in American citizenship to be an “endorsement of atrocities: the importation of African slaves, the slaughter of Native Americans, the rape of ancient forests, and the Vietnam War.”

But today, American national shame comes from a different source: national inadequacies, shortcomings, and failures. While harming others has typically been a source of shame for powerful, dominating countries, feelings of inadequacy have been a source of shame for weaker, dominated countries. What’s new for Americans is that they feel their once-powerful country weakening.

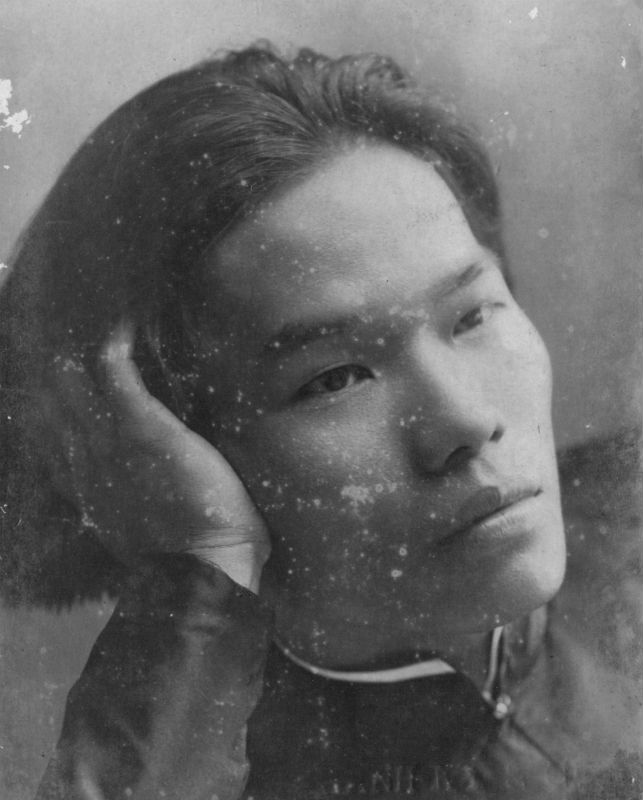

If Rorty is right that we need national pride to improve ourselves, how do we transform our national shame to pride? Americans can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh (1900-1943), an influential Vietnamese anti-colonial thinker who harnessed national shame for productive purposes in Vietnam in the 1920s.

Vietnamese thinkers of the early twentieth century lived under French colonial exploitation and humiliation of their country. The problems they faced are different from ours, but some of their diagnoses of the ills of their country feel familiar. They, too, complained of anti-intellectualism and lack of moral leadership within their own society, among other perceived national shortcomings.

At the turn of the century from the nineteenth to twentieth century, some Vietnamese thinkers adopted Social Darwinist ideas from Chinese thinkers, arguing that Vietnam fell to French colonial rule because Vietnam was weak. This weakness, they argued, was attributable to a lack of robust intellectual culture and inability to modernize. They criticized Vietnamese who held onto old Chinese Confucian ideas and urged Vietnamese to adopt new Western liberal ideas to survive, ideas that presumably made the West powerful.

By the 1920s, Social Darwinism’s influence was being supplanted by the rising influence of “radicalism,” a term used by Hue Tam Ho Tai to describe a preoccupation “not with survival and competition but with freedom and the relationship between the individual and society.”[2] This younger generation also complained of anti-intellectualism and lack of moral leadership, but now saw “symmetry between the national struggle for independence from colonial rule and their own efforts to emancipate themselves from the oppressiveness of native social institutions and the deadweight of tradition.”[3]

The most influential figure of this period is Nguyễn An Ninh. Jailed by French authorities numerous times for his anti-colonial activities, Ninh wrote articles exposing the brutality and hypocrisy of France’s “civilizing mission” addressed to French citizens in the metropole. But when addressing his compatriots, Ninh criticized Vietnamese, urging them to transform their selves and Vietnamese culture. He saw self-cultivation as a prerequisite for political action and structural change.

In a speech delivered in Saigon in 1923, Nguyễn An Ninh shamed his own country for its poor intellectual output compared to other nations:

“At present, as India and Japan provide thinkers and artists whose talent or genius radiates alongside the talents and geniuses of Europe, Annam is still only a child who does not even have the idea or the strength to strive towards a better destiny, towards true deliverance.”[4]

Nguyễn An Ninh wanted his countrymen to feel ashamed about Vietnam’s past and present intellectual weakness and their lack of “great” thinkers, but this was supposed to motivate them to become “great” rather than drive them to despair. Their task, he exhorted, was to muster a creative spirit to “guide the footsteps of the people and enlighten their path. We need artists, poets, painters, musicians, scientists to enrich our intellectual heritage.”

The standards that Ninh endorses to assess the value of a nation are not necessarily “European” (e.g., rationality and autonomy), but rather concern whether a nation has a heritage of intellectual culture, specifically literary and artistic works, and, more importantly, whether these have endured to guide and invigorate future generations and inspire the world at large. He writes, “Many people owe to their culture the duration of their name, their influence in the world, and the messianic role that they play in the world.”

Unfortunately, Ninh thinks, Vietnam’s standing in the world is low, even compared to other nations colonized by the West: “India, despite its oppression by the English, has its philosophers, its poets, its intellectuals, its leaders who lead actions of the masses.” By contrast, “Annam figures like a pygmy next to a giant, because India has a most glorious past.” Compared to nations like India and Japan, whose thinkers “radiate alongside the talents and geniuses of Europe, Annam is but an infant.” For Ninh, the literary and artistic achievements of Vietnamese are weak compared to the heritages of other peoples. This “is not the kind of heritage that will help give us more vigor and life to our race in the fight for a place in the world.” Shame, rather than envy, best describe Ninh’s feelings towards his own country.

Ninh was not the first to shame his compatriots for their poor intellectual output. A generation before Ninh, the Vietnamese nationalist Phan Châu Trinh said that a number of European thinkers such as Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu had “contributed to unshackling their compatriots from autocratic rule” and that only “Confucius, Mencius, Mozi, Laozi, or Zhuangzi…in ancient China might be compared” to those European men. But in Vietnam from the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) on, “there has been no person of such caliber.”[5] In a public speech in 1925, Phan Châu Trinh asked, “In our country at present, is there a person who may be called moral philosopher? Even since the time of the Lê dynasty, is there anyone who may be called a moral philosopher like those I mentioned?”

The U.S. is different from the Vietnam that Ninh describes. There is no shortage in the U.S. of “great thinkers” of the kind that Ninh and Trinh accused Vietnam of lacking. We have Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Susan B. Anthony, James Baldwin, Noam Chomsky, Ruth W. Gilmore and many more.

However, for Ninh, “great” thinkers matter only to the extent that their ideas guide, inspire and invigorate future generations and the world at large to undertake their own projects. Great thinkers withstand the test of time. American philosophers, artists, poets, painters, entrepreneurs, musicians, filmmakers, and scientists have inspired not only generations of Americans but also countless others around the world. This global influence has been a source of American national pride. We might feel proud knowing, for example, that Vietnamese writers in the early twentieth century were inspired by Abraham Lincoln, writing,

“From the story of Lincoln, we know that fate does not control individuals if they know how to establish and show their resolve. From the story of Lincoln, we know that any misery can be reduced if the politics of one’s own country are democratic. From the story of Lincoln, we know that his accomplishments were in all cases due to his inner virtue. If we aspire to the accomplishments of Lincoln, we must first develop his virtues.”[6]

But to what extent do “great” Americans still inspire Americans?

Americans should take advantage of the fact that we already have great American thinkers. Through the lens of Ninh, one way for Americans to overcome American national shame is to read (or listen to) the great Americans, not to parrot what they have said, but to be genuinely moved by them. We should reread and critically engage with them until their ideas help give shape to our own and invigorate us with moral guidance for the new problems we confront.

Ninh exhorted his compatriots to become great themselves because he was ashamed of their habit of parroting the greats of other nations. The central problem for Vietnamese youth was a crisis of moral knowledge and absence of their own great ancestors to inspire or guide them: “Vietnamese youth is caught as if in whirling waters, not knowing where to swim toward. Faced with a moral choice, it does not know on which morality to base its actions and its judgments.”[7] Turning to Chinese ideas for prepackaged moral guidance would not work, he thinks: “Haven’t the so-called elite fashioned by Chinese books been forced to cling to Confucian ideas like shipwrecked people to a raft?” Similarly, the Vietnamese should not simply adopt French or European values without struggling on their own to make such ideas meaningful to themselves:

“The future that we desire will not come to us in a dream. It is not enough to mark in gold letters on the front of public buildings: liberty, equality, fraternity, in order for liberty, equality, and fraternity to reign among us… You claim from others things that they cannot give you…things that you must acquire by yourselves.”

For Ninh, his generation’s task is “finding a solid intellectual heritage that can serve as the first stone on which to build our dreams.” This heritage would be solid only if it was a result of their efforts, rather than the work of others: “The current generation needs new ideals, their ideals; a new activity, their activity; new passions, their passions.”

Fortunately, we Americans already have a solid intellectual heritage. Learning from Ninh would mean going back to great American thinkers and re-engaging them in order to regain national pride. Perhaps many of us have never even read their writings, despite hearing about them or the occasional famous quote by them. Many of us ought to read our “greats” for the first time.

Ninh urges the youth to be curious to learn from great thinkers:

“What we need is curiosity under all its forms, a curiosity that is the last hope and last sign of life, that is capable of every audacity in order to quench its thirst, a curiosity that burrows, seeks, searches, and dissects everything that is life in others so as to find the remedy which will give new vigor to a weakened blood.”

The greats should not be imitated but used as springboards. What the Vietnamese need “is not servile imitations that far from liberating us attach us to what we imitate. We need personal creations that come from our own blood or works that come from an actual change within ourselves.”

Learning from great Americans will not immediately heal the ravages of coronavirus, nor will it instantly cure the country of racism and rampant inequality, nor will it suddenly unify those across partisan lines in order to address common challenges. These problems can only be resolved through the sustained energy of creative and cooperative Americans. But rereading the greats of our country is a way of gaining the requisite pride and unity to generate such energy. Their moral guidance is a “first stone on which to build our dreams.”

Notes

[1] Richard Rorty, Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth Century America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), 3.

[2] Hue Tam Ho Tai, Radicalism and the Roots of the Vietnamese Revolution (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992), 4.

[3] Ibid., 3.

[4] “Idéal de la jeunesse Annamite” (Ideals of Annamite Youth) reprinted in the newspaper La Cloche Fêlée (Saigon), January 7, 1924. Unless noted otherwise, translations are mine. Annam is the name used for Vietnam prior to 1945.

[5] Phan Châu Trinh, “Morality and Ethics in the Orient and the Occident,” in Phan Châu Trinh and His Political Writings, ed. and tran. Vinh Sinh (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Southeast Asia Program, 2009), 115.

[6] Mark Philip Bradley, Imagining Vietnam and America: The Making of Postcolonial Vietnam, 1919–1950 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 31.

[7] Ninh, in Cloche Fêlée, December 10, 1923; translation in Tai, Radicalism, 72.

This essay is based on Kevin Pham’s article, ‘Nguyễn An Ninh’s Anti-Colonial Thought: A New Account of National Shame,’ published in Polity.

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago