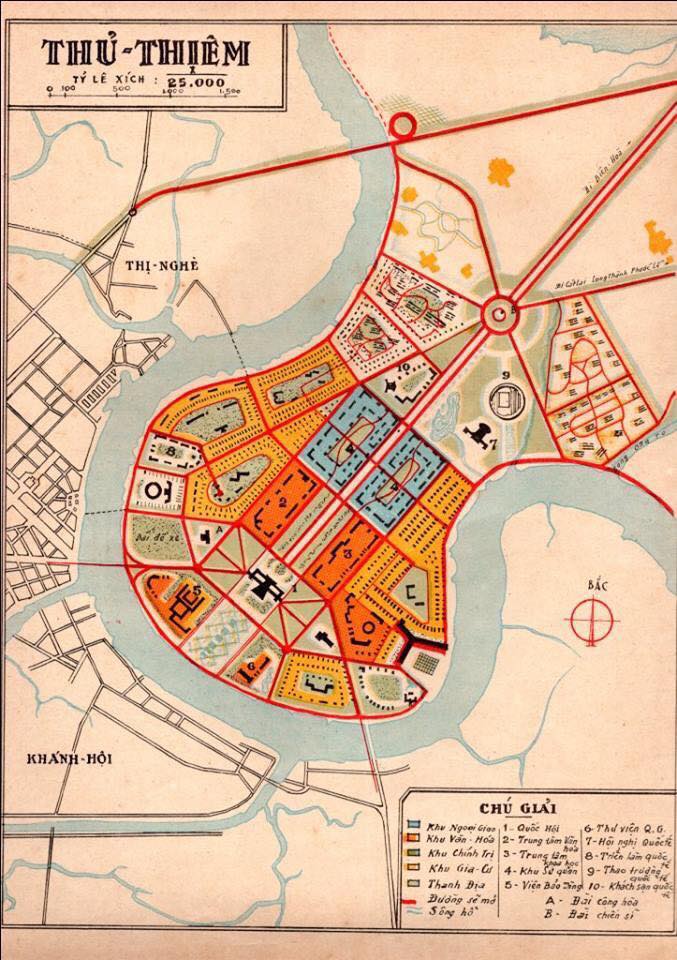

(Picture: Thu Thiem urban planning, Saigon, 1958)

By Du. T. Huynh

Five major cities (Ho Chi Minh City, Jakarta, Manila, Seoul, and Shanghai) of East and Southeast Asia have been the most powerful economic engines and trade centers of their countries for centuries. However, they have performed very differently for the last six decades (see Table 1). Around 1960 these cities’ GDP per capita were in the range of one to three thousand dollars, with Manila the wealthiest and Ho Chi Minh City the poorest. By 2015, the rankings of the five cities in terms of GDP per capita have changed substantially (in the range of 5-30 thousand dollars) with Seoul at the top and Manila and Ho Chi Minh City far behind. Moreover, rankings of livability and competitiveness and infrastructure indicators show the same results. Seoul is the most competitive and livable; Shanghai is close to Seoul and much better than the others, with Ho Chi Minh City the least.

Table 1. Selected indicators of five cities

|

Seoul |

|

|

|

|

|

Value |

Index |

Shanghai |

Jakarta |

Manila |

HCMC |

| GDP per capita of five cities at 2015 prices |

| 1960 |

2,327 |

100 |

71 |

64 |

142 |

41 |

| 2015 |

29,671 |

100 |

56 |

48 |

29 |

18 |

| Growth 1960-2015 |

12.8 |

|

10.0 |

9.6 |

2.6 |

5.7 |

| Infrastructure in 2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Roads per million people (km) |

798 |

100 |

92 |

85 |

51 |

63 |

| Metro per million people (km) |

32 |

100 |

76 |

0 |

18 |

0 |

| Water per capita (l/day) |

295 |

100 |

95 |

30 |

46 |

51 |

| Electricity per capita (kWh/year) |

367 |

100 |

128 |

89 |

46 |

60 |

| Proportion of skilled labor (%) |

53 |

100 |

87 |

37 |

76 |

49 |

| Doctors per 10,000 |

29 |

100 |

86 |

38 |

35 |

51 |

Source: Huynh (2020)

In “Making Megacities in Asia: Comparing National Economic Development Trajectories” published in Springer, 2020, the author gave six possible explanations for these patterns. They are also meaningful lessons for Vietnam and other developing countries.

First, the national development strategy matters for the development of cities. South Korea and China have consistently followed export-led industrialization strategies by reserving resources for competitive industries in urban areas although both governments had programs that were somehow import-substitution, such as heavy and chemical industries (HCI) in South Korea, or “against” the market mechanism, such as the promotion of state-owned enterprises in China. As a result, they have achieved high economic growth for many decades, and their competitiveness has been significantly improved. After several decades of high economic growth, they have been able to direct significant portions of resources to rural areas, although in China land takings detract from rural incomes.

The situation has been mixed in Indonesia and Vietnam. There have been standoffs between the export-led and import-substitution industrialization strategies. Furthermore, like the Philippines, Indonesia reserved significant resources for rural and agricultural development very early through their green revolution programs; this might have been necessary given the many islands needing attention. In the case of Vietnam, the rural-urban development strategy has not been clear and consistent. Therefore, the economic growth in Indonesia and Vietnam has been just fine for several decades, and chances to escape from the middle-income trap are not obvious. The Philippines is the worst case. It has not had clear and consistent development strategies. Thus, this country has gone from the most developed in the early 1960s to nearly the bottom in 2015.

Second, the share of budget revenue that a city is allowed to retain for its expenditure is critical. Cities need a fair share of their revenues for their expenditures. When major cities, which are usually more affluent, are exploited too much and allowed to keep only modest portions of their revenues for their expenditures, the development of both cities and the country is harmed. With reasonable resources, major cities can enhance their competitiveness and livability to become the real engines of growth to speed up their country’s development. Seoul and Shanghai have had large budgets both in absolute value and proportion of GDP, which has helped these two cities build adequate infrastructure.

In contrast, modest budgets in Ho Chi Minh City, Jakarta, and Manila have been a big problem for the development of these cities, as well as their countries. It is easy to explain the differences in infrastructure between Shanghai and Ho Chi Minh City, Jakarta, and Manila. For example, the GDP per capita of Shanghai and Jakarta in 2015 was close, but the expenditures of the municipal government of Jakarta were just less than one-fifth of that of Shanghai.

Third, consistently pursuing long-term strategies is important, while focusing too much on short-term issues with vague visions and simple panaceas cannot help a city solve its problems. Seoul and Shanghai have followed clear development strategies, which have been consistent with their national strategies. They have had clear visions for developing their cities to become globally competitive. They have focused on dealing with key issues to enhance their competitiveness and create more formal and high-paying jobs. They have focused on building key infrastructure components, especially the public transport systems based on mass transit lines, as we know no megacity in the world has been able to deal with traffic congestion without an efficient mass transit system. These approaches have enhanced their competitiveness and livability. As a result, most citizens have formal jobs, use mass transit, and live in apartments. This pattern is especially obvious in Seoul.

In contrast, there have not been clear visions and strategies in the other three cities. These cities’ governments have reserved too much effort and resources for dealing with short-term issues instead of pursuing longer-term strategies. The major strategy for dealing with traffic congestion is to build more roads and flyovers instead of building mass transit systems, limiting the feasibility of high-rise apartments and offices. As a result, significant proportions of the citizens in these cities have to work in the informal sector, using motorcycles and live in ill-equipped row houses. Regarding public transport, the conventional public transport systems (mass transit and conventional buses) have been well functioning in Seoul and Shanghai, while those in the other three cities are modest. The public transport in Manila accounted for 69 percent of the ridership, but the jeepneys (small buses) accounted for the majority.

Fourth, public entrepreneurship with powerful supporting coalitions is important, while political terms are not necessarily a major constraint for achievements. There have been public entrepreneurs in all five cities, but the degree and frequency are very different. In the case of Seoul and Shanghai, there have frequently been public entrepreneurs supported by strong coalitions to pursue their goal of becoming highly competitive. The supporting coalitions in Seoul and Shanghai are powerful, persistent, and cohesive, especially in the first periods. In contrast, there have been zigzags in other cities; there have been some public entrepreneurs, but they have not been frequent and persistent. Furthermore, supporting coalitions have not been especially strong and cohesive. They have frequently changed, especially in the case of Jakarta and Manila. In the case of HCMC, the governing coalitions were strong and cohesive from 1975 to the mid-1990s, but they have been much less powerful and less cohesive for the last two decades.

In addition, political terms should not be a major constraint for achievements. In the nature of public choice, politicians usually seek short-term performance, and their political term constraint is significant. However, this was not the case for Seoul. For over three decades, most mayoral terms were less than two years, and just a few had four-year terms, but the achievements were significant. In contrast, both Jakarta and Manila have had the top leaders in charge for ten years or more, but their performance was quite modest. Contrast is seen in Ho Chi Minh City, where achievements from 1986-1995 were significant, while those in the last decade were less impressive.

Fifth, master plans have limited roles in the development path of a city. There is a myth that master plans play significant roles in a city’s development. However, this myth is not true; in reality, urban planning is a technical and political process (Taylor, 1998). Furthermore, Bertaud (2004) points out that in the long-run market forces build cities, and urban planners can only influence city shapes at the margin through three tools: land use regulations, infrastructure investments, and taxation. All five cities have had master plans that have frequently been changed. Unfortunately, none of them has worked as expected, especially during the cities’ rapid development periods. All cities have had ambitious master plans to deal with fundamental issues, such as traffic congestion, the inadequacy of utilities, sanitation, and housing. However, most plans were impractical. Kim & Choe (1997) pointed out the situation in Seoul: “Since the 1966 master plan [the plan for a city of five million people] was introduced, more than 20 years had passed without a revised plan that city officials could have used as a meaningful development guide.” The effectiveness of master plans has been even worse in other cities (Hamnett & Forbes, 2011).

Sixth, fragmented governments have caused problems for a city’s development, but a consolidated or centralized municipal government does not secure the success of a city’s development. There should be several levels of governments to govern a big city. However, the municipal government plays the most important role because major infrastructure and utilities exhibit economies of scale and are used for the entire city. The absence of a strong and effective municipal government causes troubles for big cities. This is the case in Manila, where power belongs to the 17 fragmented cities, which lack incentives for collaboration, while the role of the Manila Metropolitan Authority is limited. In contrast, the municipal governments of the other four cities are more or less strong, but their developments have gone in two opposite directions.

Note:

This article is an introduction to the book “Making Megacities in Asia: Comparing National Economic Development Trajectories” by the author, Springer, 2020

References

- Bertaud, A. (2004). The Spatial Organization of Cities: Deliberate Outcome or Unforeseen. Institute of Urban and Regional Development.

- Hamnett, S., & Forbes, D. K. (Dean K. (2011). Planning Asian Cities : risks and resilience.

- Huynh, D. (2020). Making Megacities in Asia – Comparing National Economic Development Trajectories. Springer.

- Kim, J., & Choe, S.-C. (1997). Seoul: The Making of a Metropolis. Wiley.

- Taylor, N. (1998). Urban Planning Theory since 1945. Sage Publications.

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

After 19752 years ago

After 19752 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy6 years ago

Politics & Economy6 years ago

Society & Culture6 years ago

Society & Culture6 years ago

ARCHIVES6 years ago

ARCHIVES6 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago