Olga Dror is interested in the education and socialization of youths under the two opposing Vietnamese governments, the Republic of Vietnam (RVN or South Vietnam) and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV or North Vietnam), during the most intense years of their civil war. As someone who spent half of his childhood in Saigon and the other half in Ho Chi Minh City, I deeply appreciate Making Two Vietnams for illuminating the sharp contrasts between the two systems that I grew up with.

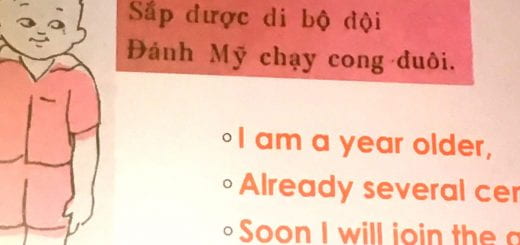

The two Vietnams were so dissimilar, making one wonder if they were both lands where Vietnamese lived. In the North, the government not only controlled cultural and educational institutions directly but also regimentally organized youth into mass organizations designed for mobilization. Policies there were aimed at indoctrinating and socializing children with the sole goal of producing a new generation of ideologically loyal fighters who deeply hated the “Mỹ-Nguỵ” enemy and who were willing to die at the call of Ho Chi Minh and his party.[1] To get a sense of this, read this excerpt from the statement by Minister of Education Nguyen Van Huyen in 1962 about the choice of authors such as Ho Chi Minh, Le Duan, Marx, Lenin, Mao Zedong, Nikolai Ostrovsky, for school curriculum. According to Mr. Huyen, their works “fostered in children the spirit to fight with stamina and a sense of purpose, with heartfelt love for the proletarian class, with a totally optimistic faith in socialism and communism, and transmitted to them the fierce vital power of Ho Chi Minh’s generation of youth to overcome all difficulties and impediments to move forward to complete their task.”[2]

Source: Olga Dror

In contrast, culture and education in the South enjoyed much greater autonomy from the government. The Southern government for the most part did not create political organizations for youths, nor did it control cultural and educational institutions as in the North. Most children were left to their natural development without much government effort to indoctrinate them about the causes of the war or the need to defend South Vietnam from the North’s conquest. As a result of government policies, children in the South were at a loss about the nature of the war and the communist enemy. Some grew up and became supporters of the government. Many joined communist or other anti-government groups. Most were perhaps apathetic as far as politics was concerned. If all Northern children were programmed to become communist soldiers, Southern children were largely free to choose their own political belief when they became adults.

[3]

Focused on the education and socialization of youths,

Making Two Vietnams provides rich evidence about the two opposing political visions in modern Vietnamese history, the republican and Communist visions, that, for two decades, existed side by side in separate territories. The former tolerated diversity and civil freedom; the latter championed a coercive unity and homogeneity. The former rejected war and contained the seeds of a liberal democracy; the latter glorified war and martyrdom, and built on the foundation of a Stalinist-Maoist dictatorship. The conflict between the two political visions involved fundamental values, amounting to what can be called a ‘clash of civilizations.’ Despite the Communist military victory in 1975, the Communist vision would prove unsustainable, as Dror notes: “in recent decades, many features of raising younger generations that were so apparent in the defeated [Republic of Vietnam] and despised by the Communists, have very gradually appeared” in contemporary Vietnam. The Communist victory turned out to be not so convincing and inevitable as it seemed in 1975.

Making Two Vietnams contributes not only to modern Vietnamese history but also to the debate on the Vietnam War. The book’s findings have many broad implications for questions about why and how the war was fought; how social actors understood its goals; whether peace was possible; what role external powers played; and whether the postwar tragedies could have been foretold. North Vietnam’s educational policy indicates that its leaders wanted to create a revolutionary society achieved through class struggle under the leadership of the communist party. This was the ultimate purpose of the war that they relentlessly pursued at horrifying costs. In contrast, South Vietnam’s educational policy reflected the goal of self-defense and survival against what its leaders viewed as “Northern aggression.” For the most part they did not attempt to force their people to fight beyond what was absolutely needed. Southern children were protected in a country ravaged by an ongoing brutal war directed from Hanoi.

While scholars have long documented how the Stalinist-Maoist state of North Vietnam controlled economic enterprises and the sources of livelihood for most people,

Making Two Vietnams is the first work that describes an essentially similar situation for educational institutions and cultural life more broadly. This completes the picture of the Northern state as one with totalitarian ambitions and significant totalitarian achievements. This totalitarian system obviously gave the North a great advantage relative to the South in mobilizing manpower through both indoctrination and coercion and in producing ‘heroic’ soldiers, about a million of whom would sacrifice their lives in the war. However, this does not mean that the North was destined to win, Dror argues, as winning depended on foreign support as much as manpower. The North’s final campaign of the war in fact saw the use of tanks, artillery, and perhaps the world’s most advanced anti-aircraft system.

This brings up the question of Hanoi’s and Saigon’s relationship with their respective patrons. In the North, children were taught, and the whole society was forced to revere Marx, Engels, Lenin, and to a lesser extent, Stalin and Mao. In contrast, despite the popular image of South Vietnam as an American neocolony, Southern children were not taught to worship any foreign gods, and certainly not American presidents. Many Southern intellectuals were openly critical of the corrupting effects of American culture on their society after 1965. Saigon cartoonists were free to make fun of President Nixon and his adviser Dr. Henry Kissinger, whereas those North Vietnamese who criticized China or the Soviet Union would soon languish in prison. Hanoi’s ideological loyalty perhaps contributed to its patrons’ steadfast support till the end, whereas the death of Ngo Dinh Diem signaled the clash of South Vietnamese and American interests and the mistrust between the partners. That mistrust would never go away, contributing to the US eventually withdrawing from South Vietnam and leaving it to confront the entire communist bloc on its own.

Given how the totalitarian state in North Vietnam controlled its society, and how hatred and the glorification of war seeped through the whole Northern society during wartime, the postwar tragedies were foretold. With the Northern state’s victory naturally came the revenge taken on their enemy who were Southerners affiliated with the Southern state and their families. Under orders from Hanoi, the proletarian revolution swept throughout the South, seizing property from business owners, forcing farmers to join cooperatives, burning books and banning trade, expelling ethnic Chinese from the country, closing down independent private newspapers and publishing companies, persecuting public intellectuals and religious leaders, and establishing direct Communist Party control in schools and universities. War, this time between Communist Vietnam and its former allies, quickly resumed after a mere four years of peace.

Making Two Vietnams does not address the remaking of one Vietnam but does suggest why war did not stop after Vietnam was reunified: the civil war in effect continued between Hanoi and various Southern classes from small-holding farmers to street peddlers to urban middle classes, as did a new war caused by the clash of Vietnamese revolutionary ambitions with those of their Cambodian client and Chinese patron.

All the reviewers acknowledge Dror’s contributions. Van Nguyen-Marshall and Wynn Gadkar-Wilcox mostly praise the book, whereas Hadish Mehta and Sophie Quinn-Judge are more critical. Nguyen-Marshall finds Dror’s work “a pioneering effort” that “represents a significant contribution to the historiography of the Vietnam War and Vietnamese history.” Gadkar-Wilcox praises Dror for her “comparative methodology,” “breadth of knowledge,” and “mastery of many languages and of different social science and humanities methodologies.” Dror’s work,” he writes, “features bold but well-supported general arguments that are likely to contribute to the field by sparking a productive debate about the extent to which the DRV’s ideology promoted hatred and the RVN’s ideology avoid anti-Communism.”

Reviewers make two main criticisms of the book. First, Nguyen-Marshall asks whether South Vietnam’s educational policy was actually devoid of state ideology as Dror claims. She points out community schools and the various civic organizations where children would have been exposed to state propaganda. While she agrees with Dror that the RVN did not explicitly denounce communism in school textbooks or children’s publications, she argues that “ideological messages regarding nation and politics were not absent [in the government prescribed curriculum that schools followed].” In a similar vein, Gadkar-Wilcox echoes this point by reasoning that “in the context of educational policy, making a claim to be apolitical is a political choice in itself.” He contends that “perhaps what distinguishes [North Vietnam] educational ideology from that of the [South] is not so much that the [North] inculcated youth to hate its enemies and the [South] did not, but that the ideological cultivation of young people was explicit in the [North], while in the [South] it was obscured within a liberal social and political framework.”

The second main criticism is about Dror’s characterization of the Southern and Northern systems. Gadkar-Wilcox believes that Dror “overstates” her case that the RVN was “anti-totalitarian,” noting the significant periods during which the Saigon government “tilted toward authoritarianism.” Mehta expresses skepticism in “Dror’s representation of the RVN as a state that offered freedom to its citizens.” His skepticism about the lack of freedom in the RVN is based on such phenomena as “rampant corruption,” President Nguyen Van Thieu’s “election rigging,” and the US concern “over the misuse of funds.” Quinn-Judge feels that Dror’s analysis of the RVN is “clinical and distant,” failing to “convey the abnormality of life in that temporary state.” According to Quinn-Judge, the war, rather than American cultural influence, created massive disruption for Southern society and “was the only reality that mattered” for many youths there.

On the DRV, only Mehta takes issues with Dror’s depiction of the DRV as “totalitarian,” noting that many Americans who visited North Vietnam during the war “found much to praise.” Those include antiwar scholars such as Staughton Lynd, Noam Chomsky, and George Wald, and antiwar activists such as Tom Hayden and David Dellinger. Mehta also questions Dror’s statement that “the

de facto agenda of the North was not nationalistic.” He believes that it reflected a mixture of nationalist and socialist goals.

Despite the criticisms, by studying a critical period in modern Vietnamese history and going beyond the war to examine the Vietnamese people and their societies,

Making Two Vietnams makes a major contribution to Vietnamese studies, provides compelling answers to many questions in the Vietnam War debate, and serves as a model for future scholarship.

Tuong Vu, University of Oregon

[1] “Mỹ-Nguỵ” or “America-Puppet” is a perjorative term referring to the enemies of the communist regime in Hanoi.

[2] Olga Dror,

Making Two Vietnams: War and Youth Identities, 1965-1975 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 210.

[3] Evidence that the Northern system was highly effective in generating unity, homogeneity, and a high dedication to the war among youth can be found in the recently published diary of Dang Thuy Tram, a communist doctor killed in action in the South.

Nhật ký Đặng Thùy Trâm, ed. Đặng Kim Trâm (Hanoi: Nhã Nam, 2005), 39, 68, 256.

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago