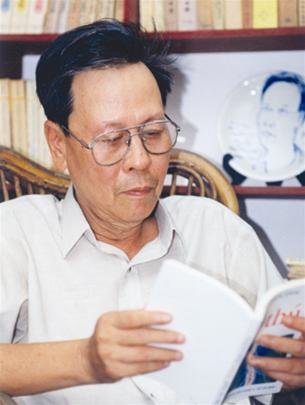

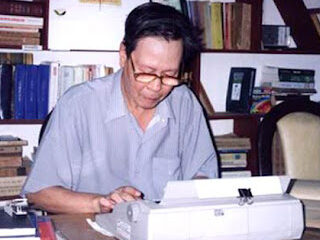

Editor’s Note: The following excerpt is from a memoir by the esteemed writer Nguyễn Mạnh Khải (1930-2008), celebrated as one of the foremost literary figures in communist Vietnam. His lifetime was marked by numerous accolades, including the Le Thanh Nghị Literature Prize (Regional Level III, 1951), the Vietnamese Arts and Literature Prize (1951-1952), the Vietnamese Writers’ Association Prize (1982), the Southeast Asian Literature Award (2000), and the prestigious Ho Chi Minh Prize for Literature and Art (2000). Originally penned in Vietnamese and published posthumously in 2006, this collection has been translated by our editor Vinh Pham. The memoir will be presented in six installments.

Political Essays – 2006

Nguyễn Khải

4.

During the decades of war, each Vietnamese person completely forgot their own material and spiritual needs in order to live like everyone else, to think like everyone else, to live and die together. The theory of Marx and the leadership role of the Communist Party were exalted to the utmost. Because individual fates were intertwined with the collective and the nation, coinciding closely with the political goals of the ruling party and the ambitions of the leaders. However, even for generations who participated in the war, living in a society and politics of a country at war was an unforeseen disaster. In collective war, individuality was pushed aside, and it could be trampled upon without any loss, as war demanded unanimity, timely orders from many heads, without time for debate, right or wrong, involving the participation of many leaders. Furthermore, if a leader miscalculated, they would immediately be punished by the opponent. Without awakening early, their career could collapse.

In times of peace, it’s only the people who face the government, different rights, different aspirations, a hundred thousand different things within a community: ethnicity, religion, culture, living conditions… that were temporarily forgotten and set aside for greater concerns. At this moment, they all rise together, demanding, and each individual sees what they demand as the most important, the most urgent.

Independence has been achieved, freedom has been gained, so how can the happiness of our nation be forgotten? But the people must find opportunities to speak, where to speak, and what means to use to speak. Speaking to organizations, to the associations they belong to as members, no one listens. Speaking through the press, no newspaper dares to publish. Writing petitions and sending them to authorities with jurisdiction never receive a response. So what should they do? They don’t dare to create chaos, and lawful protests don’t have a precedent yet.

Those who stand upright and express their discontent at meetings are immediately suppressed by those who have the opportunity, immediately recorded by security agencies, no longer able to be promoted or receive a raise, only waiting for retirement. But the people still have a way to vent their dissatisfaction by creating many political satire stories. There’s nowhere else in the country with as many satirical stories as Hanoi, because it’s the administrative capital, where daily events of the court, both real and fake, overflow in every café.

Unable to publish in newspapers, they resort to mouthpiece newspapers, as spoken words fly away and cannot be compared to written ones. They seem harmless but cause countless harm. They create public opinion, which can’t be arrested or killed. This tangled public opinion keeps expanding, covering everything and everyone, becoming a new standard for a generation. This new standard is called “let it be.” It refers to others, the government, anyone or anything that doesn’t directly relate to one’s own interests.

After a long time of blending into the collective, the individual separates from it to find itself again. However, this rediscovery often leans towards the negative side of human nature, aiming at personal gains, thus failing to achieve true flourishing, genuine freedom, an environment for unique creativity that absorbs both personal characteristics and the zeitgeist in its pioneering element.

Here I want to add, natural freedom nurtured in a democratic environment is the freedom of dedication, whereas newfound freedom, escaping from oppression, often has destructive tendencies, seeking revenge to make up for the years of deprivation. The comparison between the centuries-old freedom of a democratic society like the United States and the newly acquired freedom of the Soviet Union is clear enough. Because it wasn’t prepared, wasn’t educated, all the instincts of humans unleashed en masse would cause chaos for the community, more so than building. Democracy and freedom need time to get acquainted, to learn how to use and protect, to distinguish the boundaries between the individual and the community, only then can they blossom and bear fruit in the form of laws and new customs.

5.

A country invaded, then colonized, its people turned into slaves without legal protection, making it difficult even to express personal consciousness within each individual. Personal consciousness is awareness of one’s uniqueness, of one’s potential contribution to the community, distinct from anyone else due to one’s own unique perception, way of thinking, from which… Personal values are only recognized, honored in relatively free societies, with relatively good interpersonal relationships. In the capitalist society that we often view as quite negative, it often raises cries for help, protecting traditional individual values, as money diminishes human worth, erodes ethical foundations, and disrupts social relationships.

People are living in relative comfort, yet still at odds with it, wanting to escape it because their spiritual needs are not satisfied. We often use these stories as evidence to show the degradation of individuals living under a capitalist regime. So, what about citizens of a socialist regime? No one complains. Even writers, who are responsible for nurturing the spiritual lives of their fellow citizens, remain silent. There was a Russian writer, Vladimir Dudintsev, who wrote a book “Not by Bread Alone,” which was criticized by the literary community of the Soviet Union. He was wrong, as socialist countries highly value the spiritual lives of their citizens. They read books a lot – on trams, buses, in parks, standing in long lines for groceries, buying tickets for ballets, listening to music – they all read attentively, as if their true lives were in the pages of books.

Only in those moments immersed in reading do they have the opportunity to reflect on their own destinies, those of their fellow citizens, to rediscover their own unique essence that has been lost in some corner. Leaving the pages of books plunges them immediately into the whirlwind of countless meaningless tasks for mere survival. Even on days off, during what might be considered leisure time, they aren’t allowed to sit alone, ponder alone. Numerous celebrations, commitment movements, and countless meetings of various organizations consume all their remaining time… Collective life has submerged individual life, life during wartime has blurred all the habits of peacetime.

There’s always an enemy lurking somewhere, seeking a pretext to overthrow the regime either through armed struggle or peaceful means. There’s always a fellow party member, a monitoring agency, a friend watching over every thought and action, to prevent any manifestation of individualism from each member. One must always be cautious, be vigilant for revolutionary purposes, trust no one, not even friends. But one strange thing is that despite living without any real personal freedoms, we still manage to write, to create poetry!

6.

For 80 years living under the yoke of French colonialism, we were still able to lay the first bricks for the foundation of Vietnamese literature. The short stories, novels, articles, and essays from that era, published in weekly newspapers or as books, are still delightful and moving to read today. Many stories read during adolescence continue to haunt us into old age, and a series of poets and literary critics from that time, known as the colonial era, have become enduring names in the hearts of generations of readers. How could slaves rise to become such great talents? Not only in literature, but also in the arts, in performing arts. Not only in the arts, but also in science, education, in business following capitalist models, and in many traditional trades. All of this began in the early years of the century, where talents were illuminated, personal talents were strongly expressed, and they became the enlighteners, pioneers, trade leaders. They were not only great in skill but also great in virtue, exemplary figures for descendants, for posterity. These are all real stories, impossible to distort or deny. The explanation is quite simple.

The capitalist regime of France and progressive Europe was more advanced, more civilized than the feudal autocratic regimes of Asia by several centuries. This is the difference between two eras, as Phan Chu Trinh once said. During the colonial era, the colonial rulers banned, imprisoned, executed those who dared to resist them, primarily communists. The lives of the people still echoed with complaints, like in ancient times, like in the feudal era. The most impoverished were still the peasants, but society saw the emergence of many new professions due to resource exploitation in the colonies, gradually forming a capitalist economy, with urban centers and trading hubs, national and interprovincial highways, bridges and railways, daily newspapers, weeklies, and magazines. The voice of the public, silent for centuries, rose to express their identity and aspirations, though feeble, it resonated throughout the country.

Though society developed hesitantly, painfully, it was still better than the blind, dark ages of feudalism. The era was a supreme commander, with no doctrine, no political genius daring to defy its commands. Those who resisted had their theories obliterated, and politicians met disgraceful ends. Though the colonial regime was brutal, it was a product of its time, therefore it still had the capacity to cultivate many positive factors, sustainable values for the countries it colonized. As for the feudal dynasties, ruled by enlightened rulers and great scholars, they remained corrupt societies of the past. Even talents like Emperor Kangxi and Emperor Qianlong, if they continued ruling China until the late 19th century without changing their archaic system, would still fall behind, perhaps even more disastrously due to their prideful arrogance.

Despite the capitalist class having its own ugly aspects, it still managed to create environments of greater freedom and democracy, opening up new opportunities for the development of individual talents and the entire community. Let’s take another example from Russia over the past century. Under the Soviet regime, the people were entirely cared for by the state from birth to death, yet they remained dissatisfied, feeling stifled because that life was not their own, similar to that of a concentration camp. Individuals were numbered, placed in molds and rows, they only saw the crowd, unable to recognize each distinct individual, even in philosophy and literature.

Nowadays, it’s a robust society, everyone looks after themselves, people jostle and compete, seizing opportunities driven by ambitions that are no longer suppressed. Old norms have been discarded, new norms are yet to take shape, everything needs to start anew, from the national flag, anthem, emblem… Yet, it seems that hardly anyone complains about the chaotic state of affairs. They feel comfortable, content with the uncertainty of the present, because for the first time they are allowed to choose their own way of life, bear the consequences on their own, and for the first time, they recognize their own “facet of identity.”

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago