How foreign government and non-governmental agencies have promoted political rights in Vietnam (Part 1, Part 2. Part 3)

Seohee Kwak

2.2 Thematic analysis: The activities of foreign actors

Using the expert interview data and documents on 20 projects of foreign actors, I performed a thematic analysis to identify what role the foreign actors played in promoting better conditions for people’s political rights under the Vietnamese single-party regime. In choosing projects, rather than applying strict selection criteria, I sought projects on which sufficient information was available and the project objective was linked to democracy promotion. These might concern, for instance, political rights, freedom or civil society. My first analysis step was to review the data and codes I had initially assigned in line with theoretical discussions on external democracy promotion. Being flexible in alternating inductive and deductive coding, I added new codes that emerged from the collected data. This process resulted in the final codebook for the thematic analysis (Table 1).

Table 1. Codebook for the thematic analysis of foreign actors’ projects

| Code |

Description |

| Normative dissemination |

Refers to the normative promotion of democratic norms, particularly political rights and freedom, including freedom of speech, freedom of association and freedom of religion. |

| Participation in decision-making |

Refers to participation of individuals or social organizations in making decisions on policies or projects that may affect their lives, including consultations and decision-making processes at the grassroots level. |

| Social organization support

(civil society support) |

Refers to financial or technical support for activities of social organizations in expectation of civil society development in Vietnamese society. |

| Institutional reform/change |

Foreign actors directly and explicitly call for institutional reforms towards a (liberal) democracy. |

| Diplomatic channels |

Foreign actors make use of diplomatic channels (e.g., bilateral dialogue or international conventions) to officially promote democratic norms and values. |

| Direct intervention |

Foreign actors take direct interventionist action to achieve their objective of democratic changes in a country. |

| Capacity building |

Refers to awareness raising or capacity building of state actors, social organizations or a wider public within society about democratic norms (e.g., training or campaign). |

| Financial support |

Foreign actors provide financial support (e.g., grant or budget support) to the government or social organizations to support initiatives aiming to improve people’s political opportunities. |

| Interaction and cooperation |

Foreign actors try to keep good relationships with both Vietnamese state actors and social organizations. They build rapport and implement projects in cooperative terms with the Vietnamese state actors, while continuing to interact with Vietnamese social organizations. |

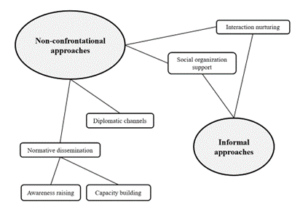

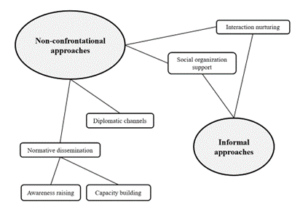

Next came distillation of salient and recurring codes into higher-node clusters, and finally into the themes. Figure 1 presents the resulting thematic map depicting the two main patterns, or approaches, through which foreign actors were found to have carried out their activities in Vietnam: non-confrontational approaches and informal approaches. These patterns and the underlying codes are elaborated below. Not every code in Table 1 was observed in the collected data. For example, it was found that none of the foreign actors studied intervened directly, such as by launching aggression by force, to achieve their goal of democracy promotion.

Figure 1. The resulting thematic map: Approaches of foreign actors.

Non-confrontational normative approaches

In most of the projects studied, foreign actors took non-confrontational approaches in which a main method was dissemination of democratic norms and values to encourage state actors to adopt and respect these. Most foreign actors were more inclined towards normative dissemination than to confrontation or interventionist mobilization, such as increasing state actors’ awareness of integrating democratic norms into their day-to-day responsibilities, or through indirect financial support, such as a grant to an initiative that could contribute to greater political rights and freedom. Capacity-building projects targeted different groups of state actors, ranging from deputies of the National Assembly to public officials in state agencies, as well as Vietnamese citizens. None of the projects sought to incite the Vietnamese people to take subversive action against the party-state. Several interviewees working for bilateral or multilateral development agencies said that their agencies tried to make the most of diplomatic channels, such as an international assembly or bilateral summit, to publicly request Vietnamese public officials and leaders to better respect democratic norms.

An interviewee in the category of state actors (no. 6, former ambassador/senior government official) said that the Vietnamese government was, in general, favourable towards and willing to build good relationships with foreign actors in development cooperation, except in two spheres: political institutional reforms and religious missionary activities. In this regard, foreign actors exhibited caution and were strategic in considering political sensitivities embedded in their cooperation objectives. Awareness raising and capacity building among state actors were the most common approaches of normative dissemination. Foreign actors rarely pushed democratic demands, such as a multiparty system or full-fledged freedom of association and assembly, as they were well aware that these norms were not favoured by their Vietnamese counterparts. Thus, non-confrontational approaches were in large part an involuntary choice, being an inevitable compromise between what foreign actors wanted to achieve and what was allowed in the given political context. In addition, several interviewees working in bilateral development agencies said that they had to take into account the economic interests of their home country vis-à-vis Vietnam.

Another finding from the analysis is that many of the projects of foreign actors sought to nurture interactions between social organizations and state actors. One interviewee (no. 33, specialist, INGO) stated that a widely used strategy was to invite public officials to workshops or policy seminars where they could discuss particular topics or policy directions together and provide evidence-based suggestions, such as survey results and field research data. By doing so, foreign actors expected that Vietnamese state actors would become gradually more familiar and comfortable with democratic norms in policymaking and policy implementation. Though it is hard to accurately measure outcomes in this regard, many of the projects in this analysis envisioned such increased awareness among Vietnamese state actors, particularly about the need to better integrate democratic norms and principles into formal state institutions.

In other cases, foreign actors provided financial support to create more opportunities for Vietnamese social organizations to actively interact with state actors. Dialogues and normative consultations are examples of such support. These were aimed not at forcing changes by applying external pressure, but rather towards generating a more favourable political environment for Vietnamese individuals and organizations to get involved and exert influence on state actors. One interviewee (no. 39, ambassador, external development agency) told me that his/her embassy took the approach of sharing international conventions with the Vietnamese government to point to areas that could be improved in Vietnamese formal political institutions. According to this interviewee, the Vietnamese government did care about being part of the international community and interacted with foreign actors, but he/she added, state actors became stubborn when foreign actors excessively raised politically sensitive topics, such as a multiparty system.

Foreign actors did target social organizations in their efforts to support Vietnamese civil society. Some projects aimed at raising awareness among ordinary Vietnamese citizens about their political rights. In these, Vietnamese social organizations often played a pivotal role as implementing agents, making use of their competencies in reaching out to people at the local level. One interviewee (no. 16, representative, international non-profit organization) emphasized that their organization did not try to provoke the Vietnamese government, but instead sought to promote the advocacy, research and consultation activities of Vietnamese social organizations within the given political system. Another interviewee (no. 44, program officer, INGO) said that his/her organization did not pursue institutional change, but supported local social organizations to implement local-level outreach and awareness raising, particularly among marginalized and vulnerable groups (e.g., ethnic minorities). Topics of this work included people’s right to identify problems in their lives, to raise their voice and to participate in local decision-making processes.

Many of the foreign actors in this study provided Vietnamese social organizations financial and technical support in which the expectation of civil society development was explicitly or implicitly embedded. Nevertheless, foreign actors were careful not to give an impression that their support might incite popular action, political contention or disruption. One interviewee (no. 42, program officer, external development agency) explained that the party-state feared the concept of ‘civil society’ or ‘CSOs’, since it did not want to see an increase in demonstrations or other forms of collective political action in the name of a free and independent civil society. Notwithstanding the structural constraints and the watchful eyes of state actors, by supporting social organizations, foreign actors aimed to pave a way forward, towards a more active role for Vietnamese social organizations in policy affairs.

My thematic analysis revealed a tendency among foreign actors to attach values to their financial and technical support to Vietnamese social organizations. Their projects endeavoured to contribute to more active and resonant social organizations. Some of the projects investigated explicitly mentioned ‘civil society development’, and even projects that did not do so displayed nuances of a commitment to expand the scope of social organizations’ activities. For instance, project objectives often entailed the expectation that social organizations would gain greater capacity and opportunities for meaningful policy engagement with less restrictions in the long term. To summarize, I found in their commitments to social organizations, and in their interactions with and support for these organizations, foreign actors conveyed the liberal democratic norms of civil society which foreign actors hope to see emerge in Vietnam.

Informal approaches

Informally nurturing interactions with state actors is the second main pattern, or approach, evident in foreign actors’ activities in Vietnam. Informal practices function as either an increased cost or a strategic detour for foreign actors. Multiple interviewees commented that personal connections and even patronage benefits were crucial for project implementation. For instance, one interviewee (no. 20, director, INGO) told me that she/he, as a foreigner, had invested considerable time and energy in building rapport and becoming friends with influential counterparts, so that projects went smoothly. Cooperation with socio-political organizations was another means of rapport building mentioned by foreign actors. Several interviewees in the category of foreign actors said that they worked closely with the VFF and with other socio-political organizations on policy advocacy.

One interviewee (no. 8, policy analyst, external development agency) said that their agency worked closely with the VFF in order to obtain permissions and smooth project implementation – although few VFF officials were supportive of cooperation with foreign actors. Another interviewee (no. 37, governance program assistant, INGO) stated that their organization tried to make the most of the unique status of socio-political organizations. Considering that the VFF can reach out to local people and elicit public opinions, their organization had conducted a project supporting local VFF officials to improve their capacity to monitor government performance more transparently and to implement appropriate policy advocacy to the government.

Another interviewee (no. 20, director, INGO) argued that local government officials tended to be more favourable and responsive to projects from which they could expect benefits, such as a promotion or financial gain. They recounted a situation in which officials indirectly demanded extra money as a bribe. Another interviewee (no. 21, director, INGO) shared a similar experience in which local government officials requested 20% of the total project budget as a so-called ‘commission’. One interviewee (no. 42, program officer, external development agency) noted that conference organizers sometimes had to give money to local police officers in order to be able to organize a conference without a surprise crackdown at the scene of the event. Although they resisted or sought to rectify such corrupt or unjust behavior, the aforementioned interviewees said that giving in to these informal practices was often inevitable, in order to carry out their activities.

At the same time, foreign actors did support Vietnamese social organizations behind closed doors and outside the formal procedures. These practices were not formally documented but raised repeatedly during the expert interviews. One interviewee (no. 11, head of department, external development agency) described informal support provided by his/her embassy. When a social organization approached them to discuss their activities and plans related to promoting civil society or democratic norms, he/she, as decision-maker, could allocate a small support grant, for instance, for an activity to raise public awareness of political rights.

Some Vietnamese groups supported by foreign actors went unregistered, as did networks of dedicated activists working on politically sensitive topics, defying the state’s control. An interviewee (no. 38, governance project officer, INGO) claimed that unregistered organizations had substantial flexibility in working on sensitive issues, but they lacked a powerful enough presence to demand change from the government. While individuals and groups working outside the conventional framework may have more freedom, they also bear limitations on their activities. Therefore, unregistered groups’ extra-institutional identity and activities bring both advantages and disadvantages.

Another interviewee (no. 39, ambassador, external development agency) told me that their embassy informally interacted with individual Vietnamese bloggers and activists to keep informed of pressing problems and public demands in Vietnamese society. In addition, an interviewee (no. 24, founding member, social organization) from an unregistered group described a secretive way of cooperating with foreign donors. One of the group members received money from a foreign donor on a personal bank account and spent it for the organization’s activities. Another interviewee (no. 45, coordinator, social organization network) mentioned that his/her network had received a small amount of funding from foreign donors to avoid the bureaucratized control of state authorities. These informal practices thus provide an extent of relief from the established formal rules and processes, giving Vietnamese and foreign actors some room to work on agreed goals together. However, these informal modalities remain sporadic and episodic.

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Politics & Economy1 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago