Politics & Economy

How foreign government and non-governmental agencies have promoted political rights in Vietnam (Part 1)

Published on

By

Seohee Kwak

How foreign government and non-governmental agencies have promoted political rights in Vietnam (Part 1, Part 2. Part 3)

- Introduction

My doctoral research departed from the argument that political action cannot be taken at face value in the context of authoritarian rule. As exploratory research, the overall objective was to provide a wide-ranging account of people’s opportunities for and repertoires of political action in the institutional setting of the Vietnamese single-party regime. One of the research questions in the dissertation was whether and how foreign actors have played a role in creating a more inclusive political environment. This essay, which is excerpted from my recently defended dissertation, focuses on the projects conducted by foreign actors in Vietnam related to promoting greater rights for political action.

While there is no universal definition of external democracy promotion adopted across all external development agencies, the working definition adopted in this study follows Grimm and Leininger (2012: 396), who defined democracy promotion as support by foreign actors “to enable internal actors to establish and develop democratic institutions that play according to democratic rules”. Foreign actors, usually the established democratic states or multilateral agencies, have long been involved in promoting democracy and democratic values, such as the political rights of expression, association and assembly, in less or non-democratic regimes. Indeed, the practice of democracy promotion has become an international norm since the inception of financial and technical support for less and non-democratic regimes spanning the 1980s and the 1990s (McFaul 2004).

Bilateral and multilateral development agencies and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) have been committed to the social and economic development of Vietnam for decades. One of their objectives has been to promote people’s political rights. Indeed, since Vietnam opened its doors to foreign actors along with other nationwide reforms (Đổi Mới) in the late 1980s, the country has faced a huge influx of foreign influence. External development agencies flocked to Vietnam to provide financial and technical support and promote adherence to democratic norms. To name a few, these norms include human rights, public participation, transparency in governance and accountability. However, as the single-party regime has remained unchanged, the role of foreign actors warrants further investigation.

This paper investigates what foreign actors have done to promote better enabling conditions for people’s political rights. Among the collected project data, the timeframe of this analysis ranges from 2005 to the present day. I first provide a descriptive account of some of the projects observed in this study. Then I present the findings of a thematic analysis of the projects, in order to identify recurring patterns across the projects and across the experts interviewed in the field. This study draws on not only document research but also five months of fieldwork conducting 50 interviews with experts working for mass organizations, social organizations and external development agencies. Although their economic and diplomatic stakes in Vietnam varied, I claim that these foreign actors have a shared understanding and objective in promoting democratic normative values in the name of external democracy promotion. I therefore use the term ‘foreign actors’ at an aggregate level in the thematic analysis.

- Foreign actors: External development agencies and INGOs

2.1 Overall profiles of activities

According to the OECD statistics (n.d.), $2.8 billion and $2.4 billion were officially contributed to Vietnam in 2018 and 2019, respectively, under the Creditor Reporting System (CRS) 1000 Total All Sector.[1] Of this sum, the amount of aid directly targeting democracy promotion was marginal. Gross disbursements for CRS 150: I.5. Government and Civil Society, Total, was $71.4 million in 2018 and $75.3 million in 2019. For the sub-code CRS 15150-Democratic Participation and Civil Society, the one most closely related to political participation and political rights, a much smaller portion of aid was disbursed: $8.2 million in 2018 and $12.7 million in 2019. This forms a very small percentage of the total aid amount provided, around 0.3% in 2018 and 0.5% in 2019. Nevertheless, it is still worth noting that foreign actors have been engaged in the agenda of participation and civil society in Vietnam.

While these numerical figures demonstrate small but noteworthy commitments of foreign actors, more specific details are needed on the projects that have been implemented in practice to promote greater political opportunities and rights in Vietnamese society. I collected documents from external development agencies on 20 of their projects and subjected these to an in-depth thematic analysis.[2] First, I grouped the collected projects into clusters of similar modalities. Two major modalities of foreign actors’ commitments were distinctive: (i) technical support for Vietnamese state agencies and (ii) grants to Vietnamese and foreign non-governmental actors.

Technical support to state agencies

A primary form of external democracy promotion is technical support, or short-term projects targeting state agencies. For example, the ‘Good Governance and Public Administrative Reforms’ (GOPA Ⅱ) project, co-funded by the Government of Denmark and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), with a budget of 60 million Danish Krone ($9.4 million) for the period of 2012-2015, had several pillars, including inter-parliamentary cooperation, joint seminars, short-term scholarships and training courses for National Assembly deputies and staff (Governments of Vietnam and Denmark 2011). Its main objective was listed as to increase awareness of democratic norms and capacity to integrate these into policymaking processes.

The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) provided a grant to Plan Vietnam to implement a project to strengthen grassroots democracy and civil society in Vietnam. The project targeted not only ordinary citizens but also state actors. With the objectives of promoting people’s participation in decision-making and building Vietnamese civil society at the grassroots level, NORAD provided over $360,000 to implement activities in 2006 and 2007 (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation 2007). To achieve this goal, Plan Vietnam provided training on the legal instruments and norms concerning people’s participation for officials at the district and provincial levels, disseminated leaflets on the norm of grassroots democracy and carried out campaigns (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation 2007). Thus, the project sought to raise awareness among local people of their rights to political participation and to influence local officials to practice the norm of grassroots democracy.

Grants to Vietnamese and foreign non-governmental actors [3]

Grants to Vietnamese social organizations and to foreign CSOs have been one of the most common forms of support chosen by foreign actors. As a part of GOPA Ⅱ, the ‘Public Participation and Accountability Facilitation Fund’ (PARAFF) was conducted in the 2012-2015 period. With the main goal of promoting participation and government accountability in law and policymaking processes, grants and technical assistance were provided to Vietnamese social organizations. In particular, PARAFF’s priority in providing grants was clearly stated as organizations committed to monitoring legislative processes of the selected themes such as democratic governance (Governments of Vietnam and Denmark 2011). The support also covered research on citizen participation in policy processes, raising awareness among the supported organizations and their partners on this topic, monitoring and feedback on better participation, and accountability provided by social organizations to state actors, alongside networking of social organizations with state actors, such as deputies of the National Assembly and officials from other government offices. From an independent, mid-term review, it was found that this project had helped many Vietnamese organizations engage more actively in law-making processes.[4]

In a similar vein, the UN Democracy Fund (UNDEF) has provided financial assistance to support Vietnamese social organizations (United Nations Democracy Fund 2014). From 2012 to 2014, the project entitled ‘Civil Society Empowerment in Advocacy and Policy Development in Vietnam’ was conducted to improve the capacity of Vietnamese social organizations to contribute to democratic policymaking processes and to network with state agencies (United Nations Democracy Fund 2014). With a budget of $175,000, the project supported 15 small advocacy activities run by Vietnamese social organizations. The project also conducted a training needs assessment and subsequently provided training for social organization staff (United Nations Democracy Fund 2014).

Also, the European Commission has implemented the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR) scheme in Vietnam. This has provided grants for activities promoting civil society, human rights and fundamental freedoms in target countries. According to the 2018-2020 grant scheme, three areas of priority were specified: (i) protection and promotion of land and resource-related rights for ethnic minorities, (ii) promotion of abolition of the death penalty and (iii) promotion of information on human rights issues online (European Commission 2019). The amounts of the grants were large, ranging between €350,000 and €450,000 for projects of a 24-36-month duration. The grants were open to not only Vietnamese social organizations but also to CSOs in the member states of the EU that work in Vietnam, as long as they involved at least one Vietnamese co-applicant.

A similar modality was observed in the grant ‘Strengthening and Supporting Civil Society in Vietnam’, funded by the Department of State of the United States. This grant program was open to US-based and foreign-based NGOs, public international organizations and other non-profit organizations to promote human rights, to support capacity development among Vietnamese CSOs and to advance transparency of the Vietnamese government. Foreseeing an implementation period between 18 and 36 months, the grant was open between $500,000 to $750,000 for one selected grantee organization (United States Department of State 2019). Its call for applications states explicitly that recipient activities should ideally be engaged in Vietnamese legal and policy reforms (United States Department of State 2019).

Limitations in activities

Any official development cooperation project planned by a bilateral or multilateral development agency and receiving more than a specified amount of finance must be submitted for review by the Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI). The MPI exerts a tight grip on project activities through its power in aid fund allocation and management. Many of my interviewees said that it was very unlikely that an external development agency would get a green light for a project that included politically sensitive elements.

The party-state has responded to the increasing influx of INGOs by setting out the playing field to its advantage. Foreign NGOs face multiple regulations in their operation. The Decree on Promulgating the Regulation on Management and Use of Foreign Non-Governmental Aid (Nghị định số 93/2009/NĐ-CP của Chính phủ: Ban hành Quy chế quản lý và sử dụng viện trợ phi Chính phủ nước ngoài) stipulates the conditions and processes that foreign NGOs should comply with in project implementation in Vietnam. A project proposal should be submitted and assessed by the MPI, the Ministry of Finance (MOF), and other related state agencies. Projects dealing with policy, law, security or religion are subject to review and approval by the Prime Minister. Moreover, Article 33 of the decree authorizes the Ministry of Public Security to supervise project implementation with an eye to political security and public order. Several interviewees in the category of foreign actors raised the problem posed by this decree, describing it as a bureaucratic as well as political constraint on their activities in promoting political rights and freedom.

As a structural intermediary to bind INGOs to the Vietnamese administrative system, the party-state established the People’s Aid Coordinating Committee (PACCOM) under the Vietnam Union of Friendship Organizations (VUFO). The main objective of VUFO, which is a socio-political organization under the VFF, is to promote mutual relationships with people from foreign countries and to take charge of foreign non-governmental aid. Thus, PACCOM is responsible for facilitating relationships between INGOs and local state agencies or local partners and acts as a focal point and manager of INGO development projects at the national and subnational levels. Considerations of areas of operation, administrative registration, field visits, project implementation and partnering local agencies are managed by PACCOM. The party-state labels this as ‘cooperation grounded on friendship’. Yet, at the institutional level, PACCOM is part of the framework for monitoring and guiding INGOs to ensure they operate within the boundaries favoured by the party-state (Salemink 2006).

According the Decree on Registration and Administration of INGO Operations in Vietnam (Nghị định số 12/2012/NĐ-CP của Chính phủ: Về đăng ký và quản lý hoạt động của các tổ chức phi chính phủ nước ngoài tại Việt Nam), foreign NGOs should submit an application to obtain a permit to operate in Vietnam. The government then assesses whether the NGO meets the requirements set by the Vietnamese formal political institutions. The Committee for Foreign NGO Affairs (COMINGO) is an assisting body to the Prime Minister related to INGO operations in Vietnam. COMINGO’s members include high-ranking officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other line ministries or agencies. Often being screened and interrogated by state authorities, foreign NGOs have no more autonomy than domestic social organizations.

One interviewee (no. 10, senior officer, INGO) recounted an experience in which they had submitted a proposal to establish an organization for research and advocacy on Vietnamese governance. After three years of waiting, the proposal was rejected without a clear explanation from the authorities. Judging by a series of questions and follow-up demands made by the competent agency, the interviewee concluded that the state authorities did not like the topic ‘governance’. An anecdotal experience that I had during my fieldwork (Box 1) aptly demonstrates state authority intervention. The issue was the topic of an international conference, to which state agents objected.

Box. 1 Anecdotal example: Forced cancellation of an international conference

| During my fieldwork, I received an email invitation from a social organization to an international thematic policy discussion on the topics of transparency, accountability and anti-corruption scheduled for 8 December 2017. The event was co-organized by several domestic and foreign agencies, including a UN agency, INGOs and social organizations. On the day of the meeting, I arrived at the hotel in Hanoi to find the conference had been cancelled that very morning. The organizing committee, standing in the foyer, said that the presenters had not been able to come. When I glimpsed inside, everything was set up but the conference room was empty.

Several interviewees whom I met later were aware of this incident. They said state authorities had forced the organizers to cancel the event, putting pressure on the presenters as well. Several interviewees suggested that authorities might have perceived the topics of the event as too politically sensitive. One interviewee (no. 34, deputy-director, social organization) who was involved in organizing the conference told me that the government had contacted the organizers and required permission the day before the conference, mentioning the Prime Minister’s Decision on Organization and Management of International Conferences and Seminars (Quyết định số 76/2010/QĐ-TTG của Thủ tướng Chính phủ: Về việc tổ chức, quản lý hội nghị, hội thảo quốc tế tại Việt Nam). In February 2020, it was revised with the same title (Quyết định số. 06/2020/QD-TTg). That decision requires both Vietnamese and foreign actors to submit details on any planned international event related to sectors such as security, religion and human rights. To carry out such an event, permission must be granted by the Prime Minister. For events in other sectors, permission should be granted by the competent authority (e.g., a minister or chairperson of the provincial People’s Committee). Among the details to be included in the application for permission are not only basic temporal and spatial information about the conference, but also participants, topics and funding sources. Article 5 of the decision stipulates that the conference shall be cancelled if the organizers do not follow this procedure. In practice, according to the interviewees, not every conference or event goes through the reporting process, and state authorities use ‘the rule’ as a card to play at their discretion. Even on similar or same topics, some conferences are tolerated whereas others are repressed. Interviewees claimed that this incident illustrates state authorities’ inconsistent and arbitrary application of restrictive rules. In this case, several interviewees said that bilateral development agencies, including the embassies of their home countries, informally expressed regret to the Vietnamese counterpart about the forced cancellation, even raising the issue at a high-level dialogue. |

Reflecting on previous civil society support experiences in Vietnam, Norway pointed out the limitations of Vietnamese social organizations in advocating on democratic subjects (Abuom et al. 2012). Since another active donor in civil society support, Sweden, noted that its pursuit of political and civil liberties remained at odds with Vietnam’s one-party political system (Forsberg and Kokko 2008: 45), little change has been observed in the party-state’s low level of toleration regarding topics of foreign actors’ projects when these were related to political rights and freedom. Among the expert interviews, several people in the foreign actor category said they often got frustrated with the discrepancy between their commitments and the lack of progress in the Vietnamese political environment, adding that state authorities resorted to coercion when their activities were perceived as undesirable from the party-state’s perspective. One interviewee (no. 8, policy analyst, external development agency) stated that the termination of operation of several bilateral development agencies in Vietnam was in part attributable to the lack of change within Vietnam’s formal political institutions, despite their continued inputs and support for change from within. This phenomenon reflects a value conflict between the party-state’s rigidity in not changing its formal political institutions and the democratic values pursued by the foreign actors.

Notes

[1] In terms of tracking aid flows released by the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC), CRS provides overall data of commitments by donors for recipient countries. According to the OECD statistics (n.d.), the objective of the CRS database is “to provide a set of readily available basic data that enables analysis on where aid goes, what purposes it serves and what policies it aims to implement, on a comparable basis for all DAC members”. Also, this amount includes not only the OECD DAC countries, but also bilateral, multilateral and non-DAC countries. The amount refers to gross disbursements, in constant 2018 US dollar prices. The data were accessed and retrieved on 23 April 2021.

[2] See Appendix 2 for the list of the projects.

[3] The projects covered in this paper may not necessarily belong to CRS 15150. Information is not available that makes possible to identify which CRS code was labelled on a project.

[4] Sidel, M. and Q.N. Pham (2015) ‘Technical Review of the Public Participation and Accountability Facilitation Fund (PARAFF)’. The report was obtained from an interviewee during the fieldwork and cannot be retrieved.

You may like

Frustrated Nations: The Evolution of Modern Korea and Vietnam

Lại Nguyên Ân Revives the Portrait of Phan Khôi Once Again

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 22 – Subjects and Sojourners

“First Thắng, Second Chinh, Third Thanh, Fourth Trưởng”: The Four “Incorruptible” Generals of the ARVN

Nam Phong Dialogues: Episode 21 – Living Abroad

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

The Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

National Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Society & Culture4 years ago

Society & Culture4 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

ARCHIVES4 years ago

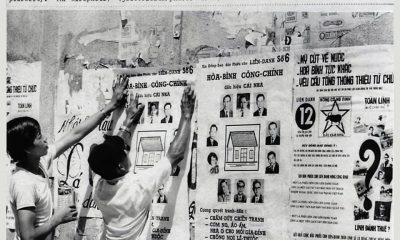

ARCHIVES4 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy3 years ago

Politics & Economy3 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoChina’s Recent Invention of “Nanhai Zhudao” in the South China Sea (Part 2: Examining the “Nanhai Zhudao” legal basis)

-

ARCHIVES3 years ago

ARCHIVES3 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 5)