Vinh Phu Pham

Today, an estimated 25,000 Amerasians reside within the United States, constituting a fraction of the total number since the conclusion of the Vietnam War. In American cinema and literature, these offspring of former American GIs and Vietnamese civilian women, commonly referred to as “bui doi” or the “dust of life,” have largely remained unseen or relegated to secondary roles. Regarded as products of the enemy, these children were systematically marginalized from Vietnamese society, often lacking birth certificates and basic education. Plagued by neglect and abuse, the majority found themselves homeless and illiterate, receiving minimal assistance from both the government and other civilians.

Today, an estimated 25,000 Amerasians reside within the United States, constituting a fraction of the total number since the conclusion of the Vietnam War. In American cinema and literature, these offspring of former American GIs and Vietnamese civilian women, commonly referred to as “bui doi” or the “dust of life,” have largely remained unseen or relegated to secondary roles. Regarded as products of the enemy, these children were systematically marginalized from Vietnamese society, often lacking birth certificates and basic education. Plagued by neglect and abuse, the majority found themselves homeless and illiterate, receiving minimal assistance from both the government and other civilians.

On the rare occasions where Amerasians do take center stage, their narratives are often depicted full of sorrow and their lives over-determined. Those growing up in the 1990s might remember the Afro-Vietnamese singer, Randy, and his heart-wrenching rendition of “Nó,” Kien Nguyen’s beautifully intimate 2001 memoir, The Unwanted, Hans Petter Moland’s 2004 drama, The Beautiful Country, and who could forget the aptly titled number “bui doi,” in Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil’s 1989 broadway production of Miss Saigon. This invisibility is not new in the history of Vietnam, however. Since the early stages of French colonialism in Vietnam, mixed-race children have always posed a legal problem for the imperial French state with many children lacking official recognition, and thus were systematically tucked away either in a Catholic convent, or shipped off the the metropole. This out of sight out of mind precedent stuck with the country as the reigning attitude towards mixed-race children throughout the twentieth century.

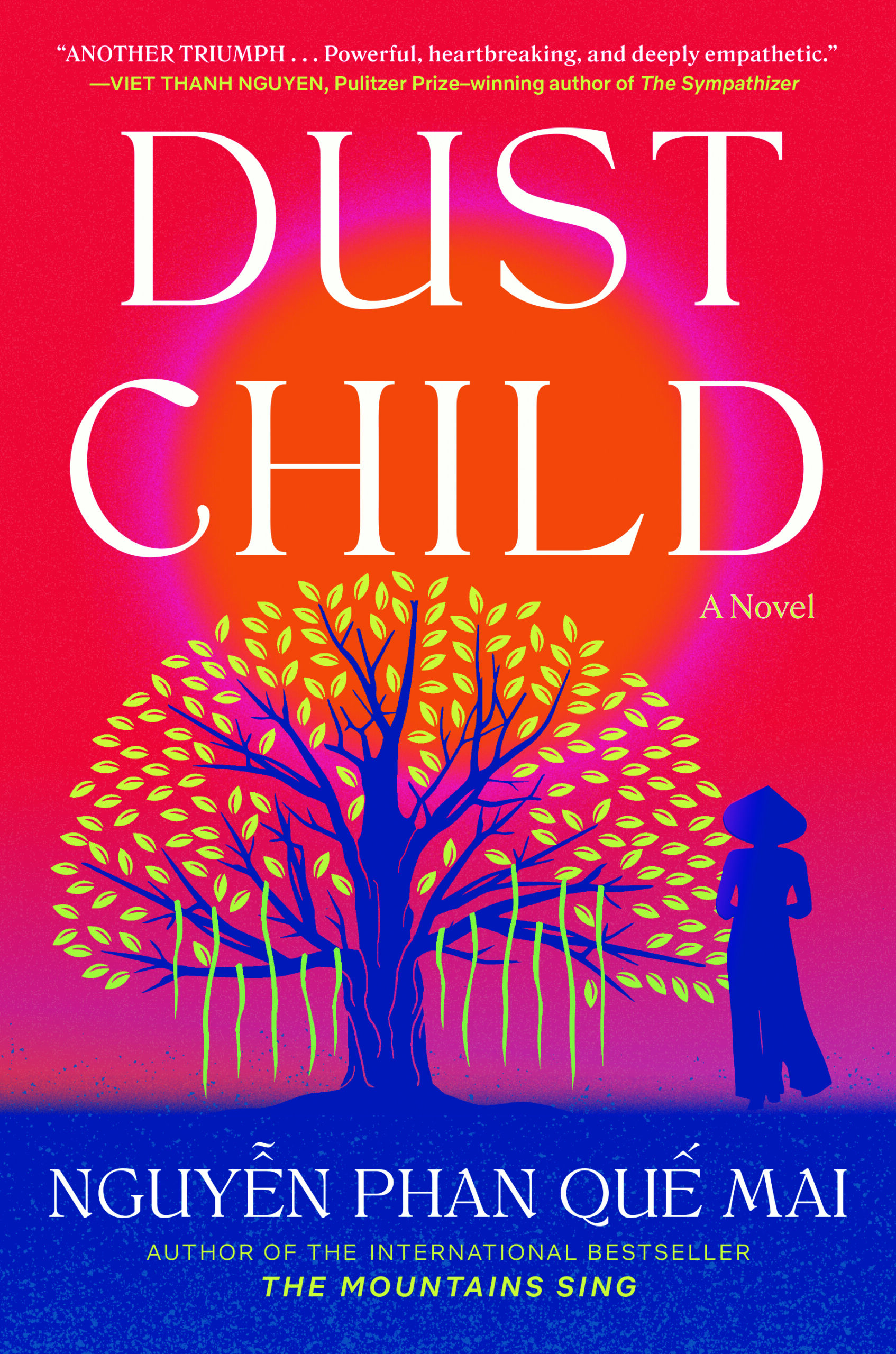

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s second novel, Dust Child, carefully addresses this history of pain and erasure, while also creating space for hope through the intricate interweaving of the lives of all the characters involved. Using data and stories collected from her PhD research, Quế Mai’s masterful narrative offers a refreshing take on what appears to already be familiar.

Over the course of some three-hundred pages and centered around one man’s struggle to reconcile with his mixed-race identity and the ravages of war, family remains the central theme that propels the plot forward. In addition to Phong, the main character, there is also a pair of Vietnamese siblings, a savvy tour guide and an American couple to round out the ensemble of characters. Here, the notion family is provided in different iterations insofar it is as much about the search of finding biological family as it is about creating family on that search. Of course, death, poverty, prostitution, displacement, and finding community are all heavy topics, but they never feel too belabored or didactic throughout the novel. Even the side characters are treated with respect and given the proper space to develop.

For those already familiar with either the genre or the thematic, Quế Mai’s light tone offers a glimpse of the new direction of Vietnamese literature in English. Yes, sorrow and memory are inescapable, but so too are moments on joy and redemption. Sentences are never too long, thoughts don’t meander to pass off as literary philosophy, and the tenderness characters demonstrate to one another humanize the very interactions that make historical reconciliation a thinkable possibility. For instance, in several scenes portraying the Vietnamese siblings’ efforts to grasp English, a delightful and self-aware humor emerges as they playfully navigate this strange language of the GIs.

For those who are unfamiliar with the genre or contemporary literature about Vietnam, Quế Mai’s writing offers an entry-way into some of the still relevant issues relating to the Vietnam War. On occasions, there are explanatory passages that give insight into Vietnamese culture, such as the rural-urban divide, popular songs and literary works, as well as the nuanced co-existence of former government and military officials within Vietnamese society, all without sounding too trite. One, of the main characters, in fact, is only later revealed to have been a military official later in the novel. This is on purpose, of course, as it is also a reminder that modern Vietnam is a dynamic society that was only made possible by its history of violence and social-shuffling.

At times, however, one does wonder whether every new novelistic work on Vietnam will make the compulsory mention of Truyện Kiều (Tale of Kieu), Vietnam’s most famous epic, as was the case here. Typically referred to as a symbol of suffering for Vietnamese women carrying out familial duty, Nguyen Du’s mentions in contemporary literature on Vietnam tends to always revert back to the rupture and re-incorporation of the traditional family unit. But must this always be the case? The critique here has less to do with the rehash of narrative devices that are ethnosyncratic, per se, than a more general issue with the burden of representation. Perhaps, in time, Truyện Kiều might no longer need an introduction nor only brought about when thinking through women’s suffering for the family unit.

Even during these moments, however, the novel remains light, gesturing towards pain, but never lingers long enough to wallow in it. Quế Mai’s feat with this novel, once again, is to push toward reconciliation and moving forward. For those who seek what Viet Thanh Nguyen has called “heartbreaking, and deeply empathetic,” this newest addition into the Vietnamese literary cannon should not be missed.

To purchase Dust Child, click here.

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Today, an estimated 25,000 Amerasians reside within the United States, constituting a fraction of the total number since the conclusion of the Vietnam War. In American cinema and literature, these offspring of former American GIs and Vietnamese civilian women, commonly referred to as “bui doi” or the “dust of life,” have largely remained unseen or relegated to secondary roles. Regarded as products of the enemy, these children were systematically marginalized from Vietnamese society, often lacking birth certificates and basic education. Plagued by neglect and abuse, the majority found themselves homeless and illiterate, receiving minimal assistance from both the government and other civilians.

Today, an estimated 25,000 Amerasians reside within the United States, constituting a fraction of the total number since the conclusion of the Vietnam War. In American cinema and literature, these offspring of former American GIs and Vietnamese civilian women, commonly referred to as “bui doi” or the “dust of life,” have largely remained unseen or relegated to secondary roles. Regarded as products of the enemy, these children were systematically marginalized from Vietnamese society, often lacking birth certificates and basic education. Plagued by neglect and abuse, the majority found themselves homeless and illiterate, receiving minimal assistance from both the government and other civilians.