Editor’s Note: The following review was published in the Journal of Vietnamese Studies, Vol. 19, Issue 1, pps. 137–143, 2024. It has been reformatted here with minimal adjustments. To see a full review of Kim Vui’s memoir that was previously published on this site, click here.

Vinh Phu Pham

K I Ề U CHINH

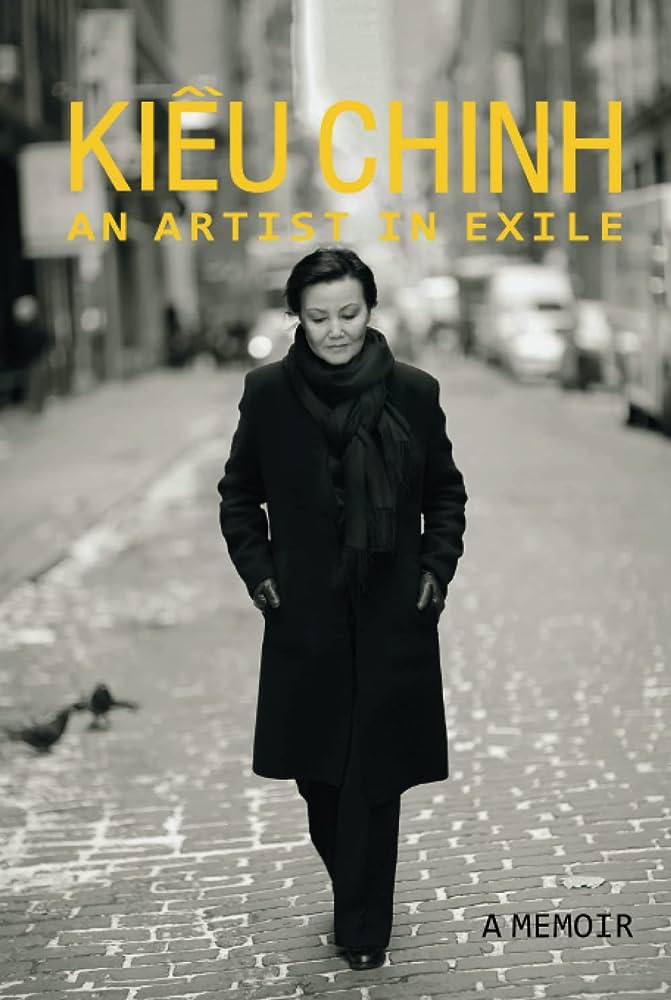

Kiều Chinh: An Artist in Exile; A Memoir.

Irvine, CA: Văn Học, 2021. 500 pages. $40.00 (hardcover).

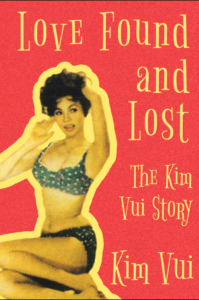

KIM VUI

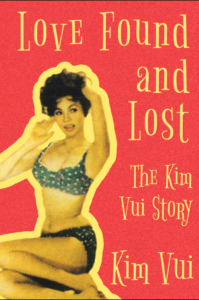

Love Found and Lost: The Kim Vui Story.

Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2022. 260 pages. $26.95 (hardcover),

$9.95 (e-book).

For cinema fans and academics interested in the former Republic of Vietnam (RVN), it has been quite a treat for two memoirs to come out in quick succession, written by two of the most iconic figures of the Sài Gòn entertainment scene during the 1960s and 1970s: Kiều Chinh and Kim Vui (née Nguyễn Thị Chinh and Nguyệt Chiếu, respectively). While typically the draw of artist memoirs is the celebrity status and private lives of their subjects, these new titles are also closely tied to the history of Vietnam’s twentieth-century wars and to the refugee crisis that led to the formation of Vietnamese diasporic communities abroad. As stars of classic films such as Từ Sài Gòn tới Điện Biên [From Sài Gòn to Điện Biên] (1970) and Chân trời tím [The Purple Horizon] (1971), Kiều Chinh and Kim Vui were both participants in constructing a vision of cinematic nationalism. Their filmography is part of an oft-overlooked cultural dimension of the South Vietnamese nation-building project. Both memoirs describe the artists’ private lives, career trajectories, and later refugee journeys, but the works also offer two distinct approaches to the memoir form: one more career-focused and the other detailing the national political climate.

The two artists’ lives paralleled one another at various points. Both Kiều Chinh’s and Kim Vui’s careers began and flourished in Sài Gòn during the height of the Vietnam War, both were married and divorced, and as mothers, both had to balance familial obligations against their professional ambitions. When Sài Gòn fell in 1975, both artists fled the country. Kim Vui’s career began in the 1950s when she started singing in tea rooms, and she later became a favorite within the Sài Gòn cabaret circuit—which led to her starring in several films such as Người đẹp Bình Dương [The Beauty of Bình Dương] (1975) and Chân trời tím. In addition to performing at clubs and on screen, she was also part of the theater group Kim Cương, as well as an entrepreneur who owned a coffee shop and later a tailoring business.

As for Kiều Chinh, she was first discovered in Sài Gòn near Hôtel Continental by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who offered her a leading role in the film adaptation of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American (1958). Though she ended up rejecting the role, this visibility would later land her the lead in Hồi Chuông Thiên Mụ [The Bells of Thiên Mụ Temple] (1957). Kiều Chinh would then go on to act in many other films, including A Yank in Viet-Nam (1964), Operation C.I.A. (1965), Chân trời tím (which also starred Kim Vui), and Người tình không chân dung [The Faceless Lover] (1971), inter alia. Inspired by her friend Hoàng Vĩnh Lộc, Kiều Chinh also established the Giao Chỉ Films Studio in 1970 (the same studio that produced Người tình không chân dung). Because of their fame and beauty, these two women were often in close contact with military officials in Sài Gòn as well as with other celebrities. The proximity between representatives of the RVN and the entertainment industry at that time afforded them unmatched insight into the relationship between the cultural and the political sphere of the nation.

Kieu Chinh and her father.

After 1975, both women became refugees and relocated to California, where they would continue their careers. While Kim Vui started another business, Kiều Chinh would continue acting—this time in Hollywood. As icons of their era, these women were sought after for their beauty and often played love interests in both Vietnamese and American war films.

In both memoirs, questions of career trajectory take center stage. Both Kim Vui and Kiều Chinh were highly accomplished performers, but they also took on the responsibility of looking after their families financially. Money is a lingering theme in the two memoirs, whether in the form of hospital bills, sudden emergencies, or the changing tides of the war. In this regard, the memoirs provide an informative account of the difficulties associated with achieving stardom in the RVN. Not only was employment not guaranteed, but the backdrop of the escalating war meant that all cultural production hinged on the constantly shifting tides of small losses and victories.

Indeed, in reading their stories, one easily feels sympathy for the authors’ changing circumstances. Despite her prolific career, Kim Vui describes a “sticky tangle of unresolved debt” (111)—revealing that the remuneration of cultural production during the RVN period was never equal to its social impact. Unsurprisingly, profits from production companies and music venues in Sài Gòn were unevenly distributed; these precarious arrangements speak volumes to the tenacity of both actors and cultural agents in the former republic. Even with money struggles, however, the connections that both women made in Sài Gòn’s elite circles would later help them to escape the country while many others were stranded. Kiều Chinh’s friend procured her a seat on one of the last flights out of the country to Manila, while Kim Vui’s American husband Bob got her safe passage and residency in Guam.

Of course, the lives of these women are more than their careers. Readers are likely to find the most intrigue in their accounts of romantic introspections, encounters, and tribulations, given that these aspects take center stage. From this angle, Kim Vui’s memoir stands out as a story of amorous redemption. As the title, Love Found and Lost, suggests, the work is sustained by a romantic vision—four of the chapter titles start with the word “love.” Spanning fourteen chapters and an epilogue, the memoir covers the singer/actress’s life from birth in 1939 to the present. It dives into her parents’ romantic troubles, offers vivid details of her own marital issues with her first and second husbands, and finally describes her rekindled love with a former CIA agent in her later years. After Kim Vui’s first marriage ended in 1963, she fell in love at first sight with her second husband, Frank, whom she met through her friend Douglas Ramsey in Đà Lạt. As she writes, “[H]e smiled, lightly, and I suddenly felt unexpectedly off-balance” (78–79). Though the two would not be permanently reunited until much later in her life, and despite Kim Vui having sworn off any possibility of a relationship with Frank, he appears and reappears in the memoir as a reminder of romantic possibilities. Over the ups and downs of Kim Vui’s career and throughout the course of the war, these romantic encounters punctuate her life and lend credibility to her image as a Sophia Loren–like icon of sensuality.

Cover of memoir.

Kim Vui’s memoir is most illuminating in its candid description of the intricate involvement of the culture industry with the RVN state. There is no shortage of encounters with influential people, ranging from political gangs like the Bình Xuyên group and intelligence operatives like John Paul Vann and Ralf Jonson to political leaders such as Prime Minister Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, General Nguyễn Khánh, President Ngô Đình Diệm, and President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu. From private meetings after shows to state-sponsored events that placed Kim Vui in front of these important figures, the memoir makes clear that entertainers occupied a tenuous space between the state and its unifying cultural aims. These various encounters between celebrity figures and politicians underscore the southern republic’s critical need for public support and its desire to forge ties with the entertainment/culture industry. Detailing all the major events in Vietnam from the 1940s onward, Kim Vui’s account—particularly its emphasis on her contact with powerful men—highlights the precariousness of women’s roles both during the war and in Vietnamese society more broadly. It is undeniable that women had a crucial role in the state-building project of the RVN, but detailed personal accounts from female celebrities involved in the film industry have, until now, been scarce. Scholars interested in how women navigated within the nexus of patriarchy and state power should find plenty of useful data in

this memoir.

Though she never worked in politics herself, Kim Vui’s proximity to political figures informs her commentaries. Possibly due to this, she confidently states, “Even more than fifty years later, I still maintain that the president had the opportunity to take corrective actions.” She subsequently wonders, “Why did he not seize that opportunity?” in relation to Ngo Dinh Diem’s response to his brother’s suppression of Buddhist demonstrations (77). Such statements and questions read as the genuine reflections of an older, wiser person who not only met the aforementioned important figures but who is also aware of the dangers of romanticizing hindsight. In Kim Vui’s telling of history, things don’t just happen; individuals are directly responsible for their actions and the consequences that follow. Because of this, Kim Vui’s Vietnam is as much an idea of the possibility of a democratic state, by and for the Vietnamese people, as it is a legitimate country that was shaped by human decisions and errors. This is apparent in the closing words of the introduction where she laments, “I also lost my country … I don’t mean lost as in the sense of carelessly misplacing car keys, or that Vietnam in any way disappeared. You can find it on a map. One can travel there … But the Viet Nam of my childhood, of my life as a young woman, is no more” (xiv). These modest reflections do not conflate the private individual with the historical outcomes of the nation; the loss of her Vietnam is not the denial of the legitimacy of the current country. Instead, they affirm Kim Vui’s own relation to the developing history of her country.

If much of Kim Vui’s narrative seems driven by romance, the main driver of Kiều Chinh’s narrative is her love for acting and cinema. This memoir runs on the long side, its five hundred pages packed with details about each project she worked on; it also includes an abundant collection of personal photos. In fact, the memoir at times feels overly detailed. For example, twelve pages are dedicated to the filming and promotion of The Joy Luck Club (1993) alone, with lengthy descriptions of the hotel where she stayed in Paris for the publicity tour, even down to the drink she ordered at a bar dedicated to Ernest Hemingway. That said, there are moments where this pacing and level of detail are much appreciated, such as the copious number of pages dedicated to the hospitalization and recovery of her son, Cường, after a tragic burn accident. In such moments, Kiều Chinh airs her fears and concerns, giving readers a glimpse of herself as a mother and as a person rather than a celebrity. Beyond the cinematic world, Kiều Chinh’s career was also defined by her involvement in many nonprofits, public appearances, and work with refugee communities, such as the Vietnam Children’s Fund and a refugee camp in Bataan, Philippines. There is no doubt that Kiều Chinh used her name and image to make positive impacts whenever possible. Despite this, however, the memoir still has an air of self congratulatory inauthenticity. While there are passing moments of raw vulnerability, the artist portrays herself as a professional, always poised, polite, and presentable. To some readers, the memoir’s sterile poetics may be off-putting or outright alienating.

In its more down-to-earth moments, Kiều Chinh’s reflections about her life’s work paint a picture of a passionate artist who regrets that her career could have been so much more. Toward the end of the memoir, she recounts all the films she worked on in Hollywood, as if for the first time. Readers who have made it to this point, however, will have already been reminded of all her cinematic accomplishments several times. This underlines the author’s constant appetite for the limelight, despite her long, prolific career. This palpable remorse about a career that could have been is understandable, as the collapse of Vietnam’s film industry after 1975 left many projects unfinished and many dreams abandoned. On top of this, Kiều Chinh had to begin anew in Hollywood. She had to show up to casting calls for the first time in her life, and her identity as a Vietnamese woman relegated her to less important roles. The underlying sense of loss in her reflections, therefore, might be seen through this specter of a circumstantially diminished career that was beyond her control.

Though some readers might appreciate this level of depth in a memoir, especially for an actress whose filmography spans well over four decades, Kiều Chinh’s emphasis on minutiae seems like a distraction from other relevant and consequential events in her life—like the war that derailed her career. The same sterility of the memoir appears in its discussion of politics: though the actress had access to the same high-powered circles as Kim Vui, Kiều Chinh keeps her political commentary to a bare minimum and avoids any direct criticism of political figures of the RVN. Unlike Kim Vui, Kiều Chinh rarely wanders into the hypothetical territory of what if? Instead, she projects a seemingly solemn acceptance of the past.

All this is to say that readers who pick up Kiều Chinh’s memoir hoping for insights into wartime politics in Sài Gòn will be left wanting more. Indeed, Kiều Chinh’s career, even at its height, was never marked by her political commentary. As a northerner who moved to the South in 1954, her livelihood was dependent on her careful balance of tenuous affiliations and acceptance. As the title of her memoir suggests, Kiều Chinh comments mainly on life as an artist in exile, providing the personal perspective of one of the most prolific Vietnamese actresses of the twentieth century as well as reflections on the artistic networks that existed in Sài Gòn before 1975. More importantly, Kiều Chinh: An Artist in Exile should be recognized as one of the more authoritative works dealing directly with the film industry in the RVN, where proper sources are often still lacking or incomplete. What Kiều Chinh’s memoir lacks in political commentary, it makes up with its deep dive into the RVN’s entertainment sector.

Read together, these two memoirs fill an important gap in the Vietnamese American canon, particularly on the lesser-investigated aspects of the culture industry of the RVN. Popular culture in South Vietnam, we are reminded, did not merely fabricate fantasies or artistic escape. The worlds of film and music in South Vietnam were, and still are, built by networks of individuals committed to the production of a shared national culture. They traversed the country’s changing borders well after Sài Gòn’s name was changed.

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago