Nguyen Lương Hai Khoi, South China Sea Research Foundation

In 2009, China sent two notes to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). In these notes, China opposed the continental shelf claims by both Vietnam and Japan, expressing China’s two-sided stance concerning the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

China’s argument with Japan about the Okinotori Coral Reef

Okinotori (沖ノ鳥島) is a coral reef comprising two rocks in the Pacific Ocean. The location of Okinotori is 20°25′N 136°05′E, which is about 1740 km southeast of Tokyo. Japan sent her submission for recognition of Okinotori’s continental shelf and exclusive economic zone (EEZ) on November 12, 2008. [1] China sent a protest note on February 6, 2009. [2].

On August 25, 2009, after Japan reported its claims for the continental shelf at CLCS, China protested again. [3] China argued that Okinotori is just a rock that cannot maintain human habitation and has no economic life. Therefore, according to Article 123 (3) of UNCLOS, this rock can neither be an exclusive economic zone nor be designated as belonging to a continental shelf.

In its response, China relied on the terms of UNCLOS to oppose Japanese claims. China used concepts expressed in UNCLOS, namely, “exclusive economic zone” and “continental shelf,” to attempt to validate its argument, and clearly differentiated the two relevant concepts “island” and “rock.” Specifically, China reminded the CLCS that Okinotori is just “rock” and argued that the Commission only has the authority and responsibility to make judgments pertaining to a feature defined as an “island.” Consequently, China claimed Okinotori is outside the Commission’s jurisdiction.

However, exactly three months later, on May 7, 2009, when Vietnam and Malaysia sent their joint submission to the Commission, China objected to that submission with an argument that seriously violated UNCLOS.

China’s argument with Vietnam and Malaysia concerning the South China Sea

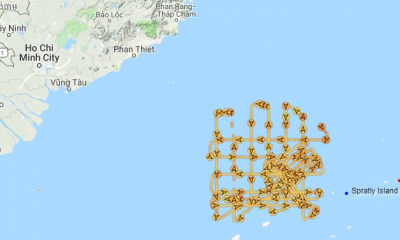

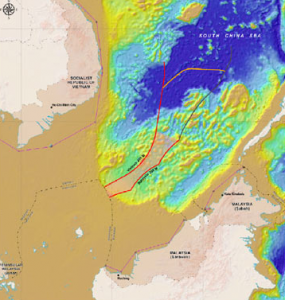

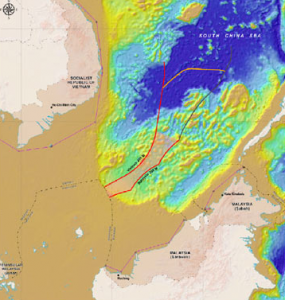

The pink zone is the “South area” that Vietnam and Malaysia claimed together.

The pink zone is the “South area” that Vietnam and Malaysia claimed together.

In its joint registration with Malaysia filed on May 7, 2009, “Vietnam holds the view that it is entitled to establish the extended continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles (M) from the baselines”, under UNCLOS. [4 ]

China sent a note to the CLCS to protest Vietnam’s registration within the same day. [5] In its note, China announced for the first time at the United Nations its belief in the validity of the U-shaped map, expressing a territiorial claim of nearly 80% of the South China Sea.

UNCLOS stipulates that each coastal state has a “territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles” (Article 5) and that each state has an exclusive economic zone that “shall not extend beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured” (Article 57). If a coastal state’s continental shelf extends more than 200 nautical miles, that country may have an “extended continental shelf.” If the above regions overlap among nations, the overlapping parts must be divided by the principle of fairness. According to UNCLOS, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, the Philippines, and China are all coastal states in the South China Sea, so each has a territory determined by the articles.

However, China claims approximately 80% of the South China Sea, leaving the remaining countries surrounding the South China Sea, including Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Philippines, only a small fracion of coaster waters. [6]

When raising its objections against Japan’s determination of the extent of its EEZ and continental shelf, China strictly adhered to UNCLOS. Nevertheless, when China presented its estimations on the sovereignty of the coastal states in the South China Sea, China blatantly violated this convention.

As such, China has directly assumed that the “islands” in the South China Sea have their own “waters,” “subsoil,” and “seabed.” The scale of these “waters,” “subsoil,” and “seabed” merge into the U-shaped line as expressed in the attached map.

All “islands” in the South China Sea are similar to Okinotori. None of these islands contain economic life, so according to the convention, there can niether be an EEZ nor an extended continental shelf of 200 nautical miles, making China’s territorial claim of 80% of the South China Sea untenable.

Some geographical features in the South China Sea may have 12 nautical miles of the territorial sea, but no matter which country owns these so-called islands, they cannot constitute a basis for claiming up to 80% of the South China Sea.

In short, when discussing geographical entities that do not have an independent economic life, China argued on the basis of UNCLOS against Japan’s claims pertaining to EEZ and continental shelf extensions of 200 nauticial miles. However, in contradictory fashion, China claimed a historically unpresedented 80% of the South China Sea, even though such a claim would fail the criteria entailed in their own objections given that China’s putative islands do not display economic life.

The reactions of Vietnam and Japan

On May 8, 2009, Vietnam sent a note to the CLCS, asserting its sovereignty based on Paracels and Spratlys on the one hand, and rejecting China’s objections based on UNCLOS on the other hand. In the official CLCS meeting on August 27-28, 2009, Vietnam reaffirmed its stance. Vietnam’s position is valid since both Vietnam and China are UNCLOS members, and therefore both countries must comply with this convention. [7]

Vietnam should pay attention to the argument that China used to oppose Japan’s claims and compare that argument with the one they used against Vietnam in order to show the world the contradictions in China’s arguments. At the United Nations, China demanded the application of UNCLOS for certain claims by other countires but ignored UNCLOS when making their own territorial claims.

Regarding Japan’s position, there is no official information about how they responded to China’s objection. Importantly, their actions towards Okinotori may suggest suitable lessons for Vietnam. The Japanese society did not care about Okinotori until 2004 when Chinese warships appeared there and suddenly announced to Japan that Okinotori could not be used to claim continental shelf extension and EEZ. [8]

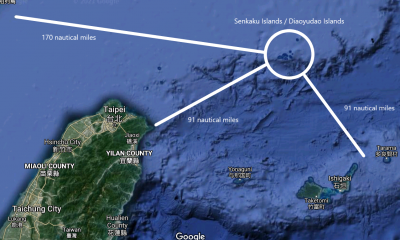

Okinotori’s strategic location is on the sea route connecting the US Guam naval base and Taiwan. Image captured from Google Map.

Okinotori is on the east side of Japan, blocking the sea route connecting the United States’ Guam naval base and Taiwan. If China can control this strategic point, China could cut off the maritime link between Guam and Taiwan. Perceiving China’s objections over Okinotori as a threat, both the Japanese government and its civil society have acted decisively. The activities of Japanese civil organizations are awe-inspiring, especially those of the Nippon Foundation [9]. Funded by entrepreneurs, the Nippon Foundation has spent millions of dollars researching Okinotori across numerous fields, including international law. [10]

(The Vietnamese version of this article was published in the journal of “Tuan Vietnam,” September 2009, but the previous page of this journal no longer exists)

Note

[1] Japan’s submission

[2] China’s note opposing Japan

[3] “China opposes submission of the Japanese continental shelf: Okinotori is just a rock.”

(中国:日本が提案する大陸棚延伸に反対、沖ノ鳥島は「岩」)

[4] Submission by Vietnam

[5] China’s note protesting Vietnam

[6] To justify this sovereignty, in the opposing note, China asserted that it had “undisputed sovereignty,” had “managed” those “islands” continuously, and their “sovereignty” is “widely recognized” internationally.

[7] Vietnam responded to China’s note.

[8] Yukie Yoshikawa, “Okinotorishima: Just the Tip of the Iceberg,” Harvard Asia Quarterly (Vol. 9, No. 4), 2006, pp. 51-61

[9] Nippon Foundation’s studies of Okinotori

[10] For example, the report by Kuribayashi Tadao, professor of Law at Toyoeiwa University, in the framework of a study by the Nippon Foundation, also relied on UNCLOS to argue that Okinotori could have a continental shelf and an EEZ. The reason is that there is no clear definition of “rock” in UNCLOS. The notion that a “rock” is a place where people cannot reside and which has no independent economic life is ambiguous. This ambiguity results from conditions where, with the development of science and technology, it is quite possible to turn an inhabited place into an area that has economic life.

Reference: 栗林忠男, 沖ノ鳥島」の国際法上の地 (Kuribayashi Tadao, Okinotori position in International Law)

In contrast, many international experts have compared Japan’s Okinotori to Britain’s Rockall. In 1988, Jon Van Dyke, a law professor at the University of Hawaii, argued for the first time that Okinotori was ineligible as a means to claim 200 nautical miles of the continental shelf. See: Martin Fackler, A Reef or a Rock? Question Puts Japan In a Hard Place; To Claim Disputed Waters, Charity Tries to Find Use For Okinotori Shima, Wall Street Journal, February 16, 2005. pg. A.1.

[11] Thuy Nguyen, Exploiting ideology and making higher education serve Vietnam’s authoritarian regime, 2022/12/1, Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Volume 55, Issue 4, Pages 83-104, Publisher

University of California Press

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

Vietnamese-America4 years ago

The pink zone is the “South area” that Vietnam and Malaysia claimed together.

The pink zone is the “South area” that Vietnam and Malaysia claimed together.