Dang-Thanh Nguyen

Abstract

This paper examines the reading experiences of Huu Ngoc (1918–) during his formative years, spanning from six to twenty years old, as a case study of the conscious and rigorous intellectual training of Vietnamese boys during the French colonial period. Adopting a first-person perspective, the analysis explores the books Huu Ngoc encountered during his primary and secondary socialization. These texts are categorized following Pierre Bayard’s framework, encompassing “obligatory” and “screen books,” as well as those he chose to read voluntarily. His reading experiences are interpreted within the broader social context that shaped his exposure to, engagement with, and exclusion from certain books. By focusing on Huu Ngoc’s interaction with specific texts, this study highlights the arduous intellectual training undergone by young Vietnamese boys aspiring to become intellectuals during the colonial era.

Keywords: Intellectual History, French Colonial Period in Vietnam, Childhood Studies, Youth Studies, Pierre Bayard.

Validation of Huu Ngoc’s Recollection of His Reading Experiences

This paper addresses a rarely explored dimension of Vietnamese intellectual history during the French colonial era: the adolescent period of individuals destined to become intellectuals with a heightened sense of obligation (Baran, 1961). Specifically, it examines their most deliberate and rigorously cultivated activity—reading. I argue that their reading experiences were fundamentally shaped by their acquisition of “screen books” (Bayard, 2010, p. 44). This adolescent phase is not strictly confined to the first 18 years of life but instead encompasses the entire period before entering university—the pinnacle of education in Vietnam at the time—or completing other advanced programs or examinations. For most boys, this educational trajectory spanned the first 20 years of their lives.

I adopt a strategic approach to discuss three successive intellectuals, categorized by the extent to which they or their families embraced Western modernization in education—considered the cornerstone of intellectual life in pre-colonial Vietnam. Phan Khoi (1887–1959), a writer raised in a traditional, high-ranking Confucian family during the transitional period between Confucian and Western education, concluded his adolescence with the 1906 Confucian examination, which was held 13 years before the final such examination and did not qualify him for court service. Dang Thai Mai (1902–1984), a literary critic from a similar family background, pursued the French educational curriculum and completed his student years in 1924 at the age of 22, before entering the École Supérieure de Pédagogie. Finally, Huu Ngoc (b. 1918), a reporter, concluded this phase of his life in 1940, also at the age of 22, after earning a French baccalaureate in philosophy and preparing to enter the École de Droit et d’Administration, which he would later leave prematurely.

The three individuals mentioned above fragmentarily recollected their perplexing experiences of acquiring Western knowledge through reading during adolescence, which served as a foundation for their later intellectual development. However, in their papers and memoirs, Phan Khoi and Dang Thai Mai largely neglected to provide detailed accounts of their acquisition of knowledge through tangible mediums, such as specific books, which could be studied objectively. This omission was common among Vietnamese intellectuals of the colonial period, making Huu Ngoc a rare exception.

Huu Ngoc remains one of the leading diplomatic reporters of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam since the French-Vietnamese War, producing numerous articles in English, French, and German to present various aspects of Vietnam to the global audience. His prominent roles included serving as editor-in-chief of the Foreign Languages Publisher and Vietnamese Studies, an academic journal available in both French and English.

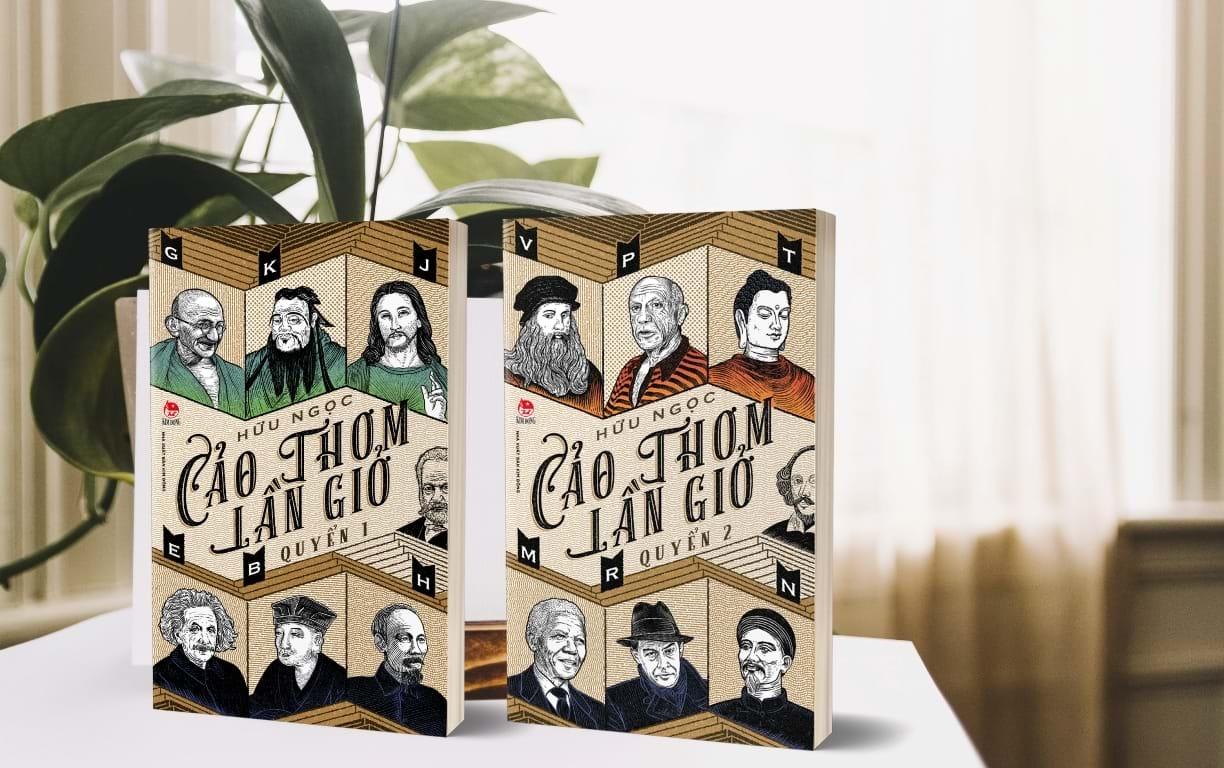

Huu Ngoc articulated his adolescent reading experiences in 30 articles published in weekend issues of the newspaper “Sức khoẻ và Đời sống”, a newspaper of the Ministry of Health of Vietnam, where he has been a key collaborator since 1998. These articles were later compiled into parts of 181 essays included in two volumes of Reflections on Classical Texts (Cảo thơm lần giở), published in 2020 by Kim Dong Publisher. His recollections vividly illuminate boys’ reading activities during the French colonial period in Vietnam through his engagement with specific books.

Huu Ngoc’s historical account is credible for two key reasons. First, he did not intentionally construct his narrative; instead, he inadvertently revisited his experiences when given opportunities, leveraging his privileged role as a significant contributor to Health & Life to reflect on familiar authors and works. Second, Huu Ngoc’s sensitivity to subjective and intersubjective realms enabled him to recount his fragmented reading experiences with depth. This ability, however, is not entirely innovative but is deeply rooted in the intellectual tradition of Vietnamese writers, as noted by literary critic Truong Tuu (1913–1999) (Truong Tuu, 2007, p. 27).

Screen Books of Huu Ngoc

Huu Ngoc’s early reading experiences primarily occurred at various educational institutions in Hanoi, the capital of French Indochina, spanning from the unstable attic on Hang Quat Street around 1923 or 1924 to his later classes at the Lycée du Protectorate. These locations were central to 24 of the 30 articles in Huu Ngoc’s 2020 collection. Within these 30 articles, he referenced 24 notable authors, 12 of whom he encountered only through his teachers’ lessons rather than by directly engaging with their texts. These indirect encounters formed the basis of his screen books, which Pierre Bayard describes as knowledge derived largely from what the reader “knows or believes he knows about the book” (Bayard, 2010, p. 47). In Huu Ngoc’s case, his screen books constituted a “shared illusion” (Bayard, 2010, p. 47), transmitted through his teachers—a mental framework essential to his knowledge acquisition process.

At the age of 5 or 6, Huu Ngoc’s family enrolled him in a private class on Chinese characters, which were considered a critical component of education in Vietnam before French colonization. He recalled, “My grandfather passed the Confucian baccalaureate examination. My father learned Chinese characters and then pursued a French education to secure a job. I attended a Chinese characters class, too” (Huu Ngoc, 2020a, p. 395). His teacher demanded rote memorization of The Three Character Classic, beginning with Mencius’s thesis: “All men are born with the same good nature” (Wang, 1941, p. 1). “My teacher was very rigid; he taught a few boys and always carried a rattan cane to whip students [if they didn’t memorize the lesson]. Going back home, to memorize lessons, I mumbled: ‘All men are born with the same good nature’” (Huu Ngoc, 2020b, p. 57). As a child, Huu Ngoc could recite the material but failed to grasp the philosophical depth of such arguments. “After less than a year [of learning Chinese characters], following the French education movement, [in 1924] my father moved me to a quoc-van class” (Huu Ngoc, 2020a, p. 417).

Twelve years later, as a student in Professor P. Foulon’s philosophy class at the Lycée du Protectorate, Huu Ngoc revisited Mencius’s ideas in the context of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s philosophy. This comparison, discussed in at least four of his articles, provided him with an intellectual framework to understand the Three Character Classic excerpt (Huu Ngoc, 2020b, p. 57). However, the deeper significance lay not in the content itself but in the socially constructed and internalized illusion of screen books, a cornerstone of secondary socialization that began with Mencius.

In 1932, while at the Lycée du Protectorate, Huu Ngoc was introduced to the concept of Platonic love—purely spiritual, idealized, and devoid of physical desire (Huu Ngoc, 2020b, p. 178). Although he had never experienced romantic love at the time, the notion of Platonic love resonated with him, facilitated by corresponding social conditions. Notably, the Northern Vietnamese intellectual milieu was influenced by The Spirit of Butterfly Encounters Deity in His Dream (Hồn bướm mơ tiên), a best-selling novel by Khái Hưng (1896–1947), published in 1932. This novel, loosely inspired by Zhuangzi, reversed themes from the classic Vietnamese play The Tale of Lady Thi Kinh (Quan Âm Thị Kính). Both works featured women—Thi Kinh and Lan—who, after societal failures, disguised themselves as men to become Buddhist monks. In the play, Thi Kinh rejects Thi Mau’s romantic advances, leading to a vengeful accusation, whereas in the novel, Lan and Ngoc, though sincerely in love, choose to remain spiritually connected but never physical lovers.

The idealized love between Lan and Ngoc mirrored the concept of Platonic love and shaped Huu Ngoc’s perception of romance, despite his lack of direct engagement with Plato’s works. Thus, Huu Ngoc’s screen books were deeply intertwined with the intellectual and cultural environment of his society, illustrating how shared illusions were contingent upon prevailing social and material conditions.

In certain instances, teachers encouraged Huu Ngoc to engage with specific texts, though he lacked the desire to explore them further. For example, a French language teacher at the Lycée du Protectorate recommended that he read the propos of philosopher Alain to develop a style of writing that was concise, clear, and appealing. However, Huu Ngoc suspected that his teachers themselves may have only heard of, rather than read, Alain’s works, as the standard salary of a native lycée teacher would not have allowed for the regular purchase of newspapers that published Alain’s propos (Huu Ngoc, 2020a, p. 13).

At that time, Huu Ngoc was following the lycée curriculum to prepare for the French Baccalaureate examination in philosophy. However, he lacked genuine curiosity about philosophy books. Instead, he passively accepted the shared illusion of books he had not read, a notion perpetuated by his philosophy teacher, Master P. Foulon. Described as “a profound intellectual, very sympathetic to Vietnam […] a bizarre one, who promoted extreme individualist philosophers from different schools” (Huu Ngoc, 2020b, p. 139), Foulon delivered passionate lectures during the 1938–1939 academic year on the works of Diderot, Nietzsche, and, most notably, the then-fashionable philosopher Bergson. Despite Foulon’s enthusiasm, these lectures failed to resonate with Huu Ngoc.

Ironically, the only Western philosopher to capture Huu Ngoc’s attention during this period was Plato, whose influence likely stemmed from the persistent efforts of his teachers across various stages of his education.

Huu Ngoc’s Reading Obligations

As a student, Huu Ngoc was subject to reading obligations that emphasized canonical texts, which, as Bayard suggests, are “particularly applied to a number of canonical texts” (Bayard, 2010, xiv). He was required to read excerpts from the works of 12 authors—a number equal to that of the authors whose works he had only heard about in lectures. The subjective meaning of these readings contrasted with his experiences of screen books.

Among his school readings, David Copperfield stands out as a book he chose to read and reread, following the suggestion of his English language teacher, Lohéné. His affinity for Dickens’ semi-autobiographical novel would later surface when discussing his preferred literary genres and his engagement with Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, a topic addressed subsequently.

Another influential text was Edmondo De Amicis’ Italian novel Heart, initially encountered in an excerpt from Manuels de lecture en quoc-van, an official textbook for primary education issued by the Direction générale de l’instruction publique de l’Indochine. This manual conveyed moral lessons emphasizing familial love, community ties, and national pride (Huu Ngoc, 2020a, p. 16). Beyond these shared values, Heart introduced Huu Ngoc to democratic ideals and the appreciation of equality in education—concepts absent in the official textbook: “the praise of democracy and equality in schools, the love […] for fellow citizens” (Huu Ngoc, 2020a, p. 17). This reading marked an early initiation into modern bourgeois morality, which later influenced the educational policies of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

Conversely, other school-mandated texts left a less profound impact. Although “the texts I learned in school often stay in my memory, even for a lifetime” (Huu Ngoc, 2020a, p. 177), his engagement with them was mechanical. For instance, Master Foulon in 1938 “highly praised Pascal and forced us to memorize some of his passages” (Huu Ngoc, 2020b, p. 161). Many years later, during a medical stay in the German Democratic Republic, Huu Ngoc serendipitously encountered Pascal’s Pensées and read it voluntarily for the first time: “I had enough leisure time to read all of this book and to think, to understand more or less about Pascal” (Huu Ngoc, 2020b, p. 161). However, he remained uninterested in delving deeper into interpretations of Pascal, suggesting that his understanding of the philosopher largely reflected Foulon’s 1938 lectures.

Voluntary Reading Experiences of Huu Ngoc

Among the 30 articles in the 2020 collection, 12 recount Huu Ngoc’s engagement with screen books, another 12 detail his school-based reading obligations, and the remaining six explore his voluntary reading experiences outside formal education. These independent reading pursuits played a crucial role in shaping his subjectivity and individuality.

First, like many boys of his age, he gravitated toward adventure and detective novels: “When I was a child, I liked to read detective and adventure novels” (Huu Ngoc, 2020b, p. 187). His enthusiasm for the adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Arsène Lupin underscores this interest, as does his long-standing engagement with David Copperfield, which he viewed partly as an adventure novel. Other favorites included Robinson Crusoe, Treasure Island, and Gulliver’s Travels. Reflecting on his childhood, Huu Ngoc recalled, “I remember when I was 11 or 12 years old, lying under the blanket, I passionately read Gulliver’s Travels in a Vietnamese translation by Nguyen Van Vinh (1882–1936), part of the reasonably priced book collection Western Literature” (Huu Ngoc, 2020a, p. 162). This early exposure to Western literature, particularly its black humor—a stark contrast to French sensibilities—broadened his understanding of Western cultural diversity beyond what his formal education offered.

Second, his voluntary engagement extended to philosophy, particularly Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, a book that occupied an intermediate space between school and personal reading. After completing the 1929–1930 school year, he was awarded several books, including Meditations. While it is unclear whether he read the text in French or Vietnamese, the latter possibility is improbable since the first Vietnamese translation by Pham Quynh (1892–1945) was published in 1931, after Huu Ngoc’s recollection. Regardless of the edition, Meditations was the only philosophy book he deeply engaged with during his school years. He attributed his attachment to the book to a sense of loneliness stemming from personal loss: “Because I lost my mother and was afraid to play with stronger and more naughty friends, I felt lonely and read everything” (Huu Ngoc, 2020a, p. 29). This emotional connection to Meditations also mirrored the sentiments he found in David Copperfield, making the latter equally impactful.

During his time at the Lycée du Protectorate, Huu Ngoc revisited Meditations as a means of self-discipline: “to learn how to strengthen my will, control myself, and find peace in the spirit” (Huu Ngoc, 2020a, p. 29). His embrace of Stoic philosophy can be interpreted as a form of individualist spiritual exercise, helping him navigate the colonial social realities of his time.

However, despite its influence, Stoic philosophy offered only partial solace. His discontent with colonial society persisted: “I lived in a burdened, boring, unauthentic society, so I strived to escape to nature to live an honest, authentic life. I wished to be a teacher in the mountains and marry an ethnic minority wife” (Huu Ngoc, 2020b, p. 391). This yearning for escape reflects a broader intellectual fascination with mountains and forests, common in Vietnamese literature from the 1930s to the 1940s. His vision of an ethnic minority wife, viewed through a social lens, aligns with contemporary urban intellectuals’ romanticized perceptions of minorities as “isolated, wild people” (Mai Anh Tuan, 2016). Thus, Huu Ngoc’s utopian aspirations, along with his reading of mountain-and-forest-themed novels, can be understood as products of the social constructions of his era.

Bibliography

Baran, Paul. 1961. “The Commitment of the Intellectual”. Monthly Review.

Bayard, Pierre. 2010. How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read. Bloomsbury. USA.

Huu Ngoc. 2020A. Reflections on Classical Texts, volume 1 [Cảo thơm lần giờ, quyển 1]. Kim Dong Publisher. Hanoi.

Huu Ngoc. 2020B. Reflections on Classical Texts, volume 2 [Cảo thơm lần giờ, quyển 2]. Kim Dong Publisher. Hanoi.

Mai Anh Tuan. 2016. “Preface”. in: Lan Khai. Truyện đường rừng [Tales from the forest]. Nha Nam & Vietnam Writer’s Association Publisher. Hanoi.

Truong Tuu. 2007. Collected work in literary studies and critic [Tuyển tập nghiên cứu, phê bình]. West – East Publisher & Labour Publisher. Hanoi.

Wang, Po-Heou. 1941. The Three Character Classic. Chung Hwa Mandarin Institution. Singapore.

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago