Politics & Economy

A Proposed Outline for a Study on Republicanism in Modern Vietnamese History

Published on

Abstract

This essay proposes a direction for studying the emergence and development of the republican spirit in early 20th-century Vietnam and its influence on the country’s political trajectory from the mid-20th century onward. The ideological conflict between communist and republican factions within the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1948 indicates that republicanism had already matured by that time, suggesting its roots extend even further into the early 20th century. The approach outlined here aims to address gaps in the understanding of modern Vietnamese intellectual and political history by shedding light on the evolution of Vietnam’s republican spirit.

Keywords: republicanism, Vietnamese history, republican factions.

1. On the Republican Spirit in Vietnam

How did the emergence and development of the republican spirit in the early 20th century influence subsequent political choices in Vietnam from the mid-20th century onward? The ideological conflict between communist and republican factions within the government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1948 shows that a republican spirit had already matured in Vietnam by that period, suggesting the hypothesis that this republican spirit was born and developed even earlier.

Reconstructing the early 20th-century history of Vietnam’s republican spirit is a necessary research task to fill gaps in our understanding of modern Vietnamese intellectual history. Our basic argument for such a study is that from the early 20th century onward, there were two opposing ideological currents in Vietnam: the republican spirit and the communist spirit. These two strains of thought began to clash in the 1930s and entered into open, uncompromising conflict after 1945. Alongside political, social, and international factors, this ideological conflict shaped modern Vietnamese history in the latter half of the 20th century, influencing how different social forces made their political choices and leading to the war between the communist and republican regimes from 1954 to 1975, as well as shaping political thought in contemporary Vietnamese civil society.

The republican spirit (republicanism) is, most generally, a political and social model based on the principle of ideological pluralism (accepting and respecting the different ideological tendencies of various social groups), on checks and balances of power, on the protection of individual rights, and on resistance to any sociopolitical structures that oppress the individual. This spirit took shape in the West during the 17th–18th centuries and continued to develop vigorously in Europe and the Americas in subsequent centuries. In Vietnam, this spirit entered through various channels, such as the political, economic, and social reforms of Japan during the Meiji era, the Chinese intellectuals’ approach to Meiji reforms, and in particular through the presence of French colonialism in Vietnam—specifically the political model established by the French from the late 19th century, as well as the education system introduced from the early 20th century.

2. Brief History of the Issue

In the body of academic work on modern Vietnamese history, the republican spirit has never been considered an important factor. Official narratives of modern Vietnamese political thought by mainstream scholars in today’s Vietnamese government depict it as an “inevitable historical” progression from “patriotism” to “communism.” Many international scholars studying Vietnam also acknowledge this model, either directly or indirectly.

Within this model of intellectual history, from the late 19th century—when Vietnam became a French colony—successive patriotic armed struggles took place but were defeated. More moderate, non-violent stances, such as those of Phan Chu Trinh and other groups, are seen as half-measures of “reformism” and therefore considered minor ideological currents incapable of fulfilling the “historical mission” of national liberation. Meanwhile, the main ideological movement, deemed most decisive in Vietnamese history, was the transition from patriotism to “proletarian revolution.” The transformation of Vietnamese thought is likewise tied to the biography of a single revolutionary leader, with two different names marking his progression—Nguyễn Ái Quốc in the “patriotic” phase and Hồ Chí Minh in the “communist” phase. Among international scholars, most Japanese researchers of Vietnam studies also write about Vietnam’s 20th-century intellectual evolution in line with this model. Some American academics adopt it in their university courses on modern Vietnamese history.

However, such a model of intellectual history does not adequately capture the complexities of Vietnam’s 20th-century political and social developments; it even contradicts what actually transpired.

3. Restructuring the Model of Modern Vietnamese History from the Perspective of Intellectual History

3.1. Fragments of a Grand Narrative

Vietnamese history since 1945 is often told through a “grand narrative” that draws a clear distinction between those who fought against foreign invaders to regain and protect national independence and the foreign forces and their “stooges” or “puppets” within the country. In this narrative, the core of the anti-invasion movement was led by the communists. The foreign invaders are identified as the French colonialists (1945–1954) and then American imperialists (1954–1975). All Vietnamese who collaborated with these foreign forces were labeled “lackeys” or “puppets” who “betrayed the nation” for personal gain. This grand narrative employs the same logic to explain every historical development from the 1920s to 1945, and from 1945 to 1975, and it also retroactively imposes an “heroes vs. traitors” paradigm on earlier periods of “national defense” — using historical pairings like Trần Hưng Đạo vs. Trần Ích Tắc, Quang Trung vs. Lê Chiêu Thống, and Gia Long. Not only today’s official Vietnamese academics but also many international scholars who study the Vietnam War have shown agreement, directly or indirectly, with this logic.

Nonetheless, there are certain events for which such logic fails to account, forcing this “grand narrative” either to ignore them entirely or to offer oversimplified explanations.

In his article “It’s Time for the Indochinese Revolution to Show Its True Colors: The Radical Turn in Vietnamese Politics in 1948” (Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 40: 3 (October 2009), pp. 519-542, Vũ Tường analyzes the conflict between “communist” and “non-communist” factions within the ranks of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1948. This analysis highlights a key upheaval that has been largely overlooked by scholarship on the Cold War and modern Vietnamese history. The article discusses many important issues, including a debate between the communist and non-communist sides concerning the spirit of the rule of law. It also examines the ideological struggles that ultimately caused non-communist members of the Việt Minh to be expelled or to withdraw from the DRV government. Lawyer Nguyễn Mạnh Tường, a historical witness, in his memoir “Un Excommunié” (A Man Excommunicated, written in French in 1989), points out that one of the core issues in the ideological conflict of 1948–1949 was the divergence in legal thinking. On one side was the communist line—placing the Communist Party above the legislative, judicial, and executive branches—while on the other side was the republican line, advocating separation of powers and viewing human rights as higher than the interests of any political party.

A study of the history of republican thought in Vietnam in the first half of the 20th century ought to use this 1948 ideological clash between communist and non-communist factions as a point of departure in tracing its intellectual origins to earlier historical periods. Political choices made in Vietnam in the late 1940s and early 1950s show that a republican spirit had matured to the point that part of the country’s elite vehemently rejected the communist path. Such maturity could hardly have emerged abruptly as a result of immediate political developments; rather, it had roots in a longer intellectual process dating back to the early 20th century.

3.2. The History of the Republican Spirit in Early 20th-Century Vietnam

The origins of the ideological conflict in 1948 can be found in the intellectual history of Vietnam in the early 20th century. That period in Vietnamese history was not solely about armed resistance to the French in pursuit of independence. There was another history, traditionally deemed “secondary,” involving the quest for an answer to an arguably more important question: Vietnam obviously needed independence, but what kind of nation would Vietnam become after achieving that independence?

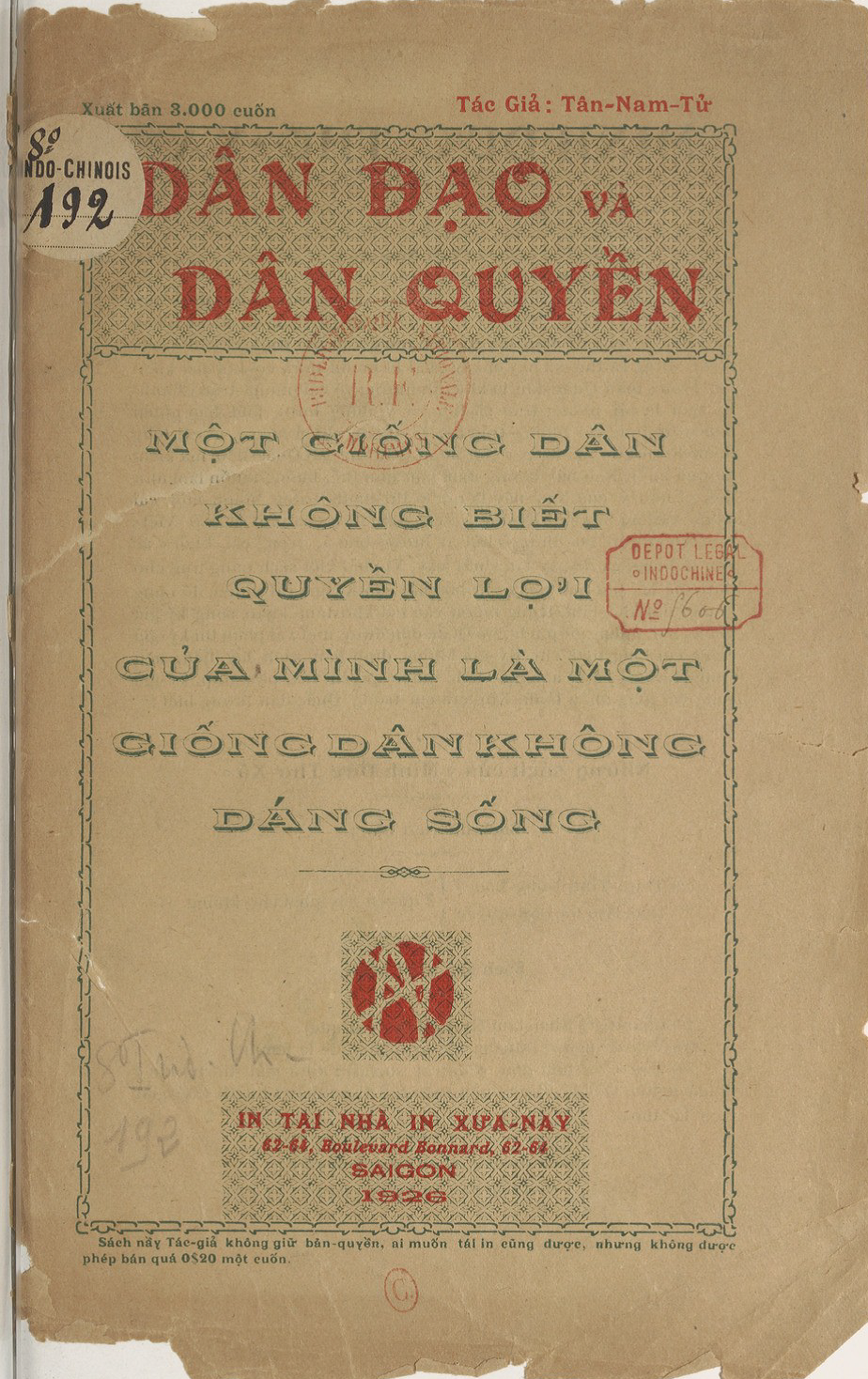

This intellectual journey began very early, in 1905, with the “Văn minh tân học sách” (文明新學策 “Civilized New Educational Policy”), a text book of the Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục (東京義塾 Tonkin Free School). It can be found earlier in the (“điều trần”) sent to Hue Court by Nguyễn Trường Tộ. It continued through the efforts of political figures and scholars such as Phan Chu Trinh, Phan Bội Châu, Phạm Quỳnh, Trần Trọng Kim, the “Ngũ Long” Nguyễn Ái Quốc group (including Phan Châu Trinh, Nguyễn An Ninh, Phan Văn Trường, Nguyễn Thế Truyền, Nguyễn Tất Thành) in France, literary circles like the Tự Lực Văn Đoàn, and many other scholars, journalists, and writers. A crucial factor was the education and media policy of the French colonial administration from the 1920s onward. These developments shaped a republican consciousness as a new sociopolitical model in Vietnam’s urban society in the early 20th century.

3.3. The Socioeconomic Foundation of Communist and Republican Spirits in Vietnam – Urban vs. Rural

The republican spirit of early 20th-century Vietnam was intimately tied to urban life. “Urban life” here is defined by the following elements:

- Introduction of new technology, such as modern printing methods, fostering the development of newspapers and publishing. Mass printing laid the groundwork for disseminating knowledge—including knowledge of the republican spirit—and formed the technical basis for civic consciousness and a democratic spirit of debate.

- Growth of cultural institutions, like the press, and of political institutions embodying republican ideals—though in practice still underdeveloped and fraught with failures—such as the Northern, Central, and Southern Representative Councils (Viện Dân biểu Bắc Kỳ, Viện Dân biểu Trung kỳ, Hội đồng Quản hạt Nam kỳ) established by the French.

- Expansion of certain cities and inter-regional transport systems built by the colonial government. This broke the isolation and self-sufficiency of traditional village culture, enabling labor mobility across all three regions. A number of large cities developed along French lines, forming a new socioeconomic force based on light industry and commerce, wholly separate from agricultural rhythms.

- Emergence of a “youth” stratum. Before widespread urbanization and inter-regional transportation, there were simply “young people” within various social strata, but not a discrete social force called “youth.” Phan Bội Châu was the first to recognize this independent social group. He founded the organization Tâm Tâm Xã—later Tân Việt Thanh niên Đoàn—which Nguyễn Ái Quốc subsequently inherited and renamed the Việt Nam Thanh niên Cách mạng Đồng chí Hội.

- Development of a modern education system introduced by the French colonial government from the 1920s onward. Though not widespread among the general population, it took root primarily in major cities like Hanoi, Huế, Saigon, and Cần Thơ. It produced an urban youth proficient in French, systematically schooled in French culture and ideology. This new urban youth, particularly those thoroughly educated in the French system, played a major role in the growth of the press as consumers of new cultural products.

These elements together constituted the social foundation for the dissemination of republican ideals in Vietnamese urban society from the 1920s onward.

3.4. Purpose and Choice

In mainstream historical descriptions of early 20th-century political thought by state-affiliated Vietnamese researchers, national independence is constantly underscored as the paramount goal of the communists. However, this focus appears to be a later construct—once the communists were in power and needed to legitimize themselves. In the pre-1945 corpus of communist writings, “national liberation” certainly appears as a goal but not the ultimate objective. On the contrary, the aim of “class liberation” in building a communist Vietnam was often stressed.

In the first systematic research on the history of modern Vietnamese thought—Sự phát triển của tư tưởng ở Việt-Nam từ thế kỷ XIX đến cách mạng tháng Tám (The Development of Thought in Vietnam from the 19th Century to the August Revolution, in three volumes)—Trần Văn Giàu labeled early 20th-century efforts to foster republican ideals in Vietnam as “bourgeois ideology” and concluded that it had proven “powerless” in fulfilling the “historical mission” of “national liberation.” Trần Văn Giàu’s notion of “national liberation” focuses on regaining independence. From this perspective, the activities aimed at developing a republican consciousness in the early 20th century—journalism, book publishing, non-violent parliamentary struggles with the colonial government—are dismissed as minor or marginal compared to armed movements, uprisings, and insurrections, especially those led by the communists. This view has been echoed by some English-language scholars as well.

However, the early 20th-century republican movement in Vietnam cannot be seen as “powerless” regarding the task of “regaining independence,” because that task was not its only (or even primary) goal. Rather, it sought to envision the future shape of an independent Vietnam—what the nation would look like after breaking free from colonial rule. The intellectual life of 1920s Vietnam was almost entirely devoted to establishing the spiritual, cultural, and educational foundations for a new, independent Vietnam in a changing historical context. Phan Chu Trinh, Phạm Quỳnh, as well as various journalistic, literary, and publishing activities of the 1920s and 1930s, and many members of political bodies like the Northern and Central Representative Councils, worked to cultivate and practice republican thought under colonial conditions. For them, building a republican spirit within Vietnamese society was the real basis of a post-colonial, post-imperial condition in Vietnam, not violent revolution.

Indeed, the history of early republican thought explains events that mainstream “revolutionary history” narratives of modern Vietnam typically omit. Without acknowledging republican history, one cannot explain the 1948 ideological conflict between republican and communist factions; orthodoxical historians in Vietnam today tend simply to dismiss republican figures who left the Việt Minh government as “cowardly intellectuals” (“trí thức trùm chăn”) who returned to the cities for fear of hardship (ignoring the fact that many of these intellectuals had previously abandoned their possessions and families in urban centers, or donated their assets to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam government, to join the resistance), or else brand them “deserters.”

Likewise, without acknowledging republican history, orthodoxical historians easily oversimplify why republicans chose to follow President Ngô Đình Diệm to the South in 1954, labeling them “reactionaries” or “lackeys.” This same disregard for republican history also means disregarding the educational, cultural, and democratic institutional achievements of the Republic of Vietnam—achievements that do not align with the grand narrative of “revolutionary war for independence.”

Besides economics and international relations, the practice of republican ideals in the Republic of Vietnam from 1954 to 1975 was the ideological foundation that explains many of South Vietnam’s achievements. Such republican practice had to contend with the short-term need for authoritarian controls at odds with republican ideals themselves—resolving post-colonial legacies such as feudal fragmentation under President Ngô Đình Diệm, or, later, implementing republican ideas during a brutal war under President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, which forced the military into a dominant political position. Yet the legislative, educational, and pluralistic political structures that grew under the Republic of Vietnam cannot be dismissed. Of course, one can cite many instances where republican ideals failed—periods of dictatorship and reliance on violence. However, there were also successes in legislation, education, and the formation of a pluralistic political system. These successes are best judged in the context of Southeast Asia over half a century ago, rather than by comparing them to today’s established democracies in the “First World,” with their advanced education, technology, and economies.

After 1954, republican-minded Vietnamese gathered in South Vietnam, endeavoring to realize their ideas amid complex domestic and international conditions. Their achievements were erased entirely after 1975, yet their legacy continued to exert a positive influence when the Socialist Republic of Vietnam embarked on its Đổi Mới (Renovation) policy in 1986.

3.5. The 1920s in Vietnamese History

From an intellectual standpoint, Vietnam’s 1920s parallel the Age of Enlightenment in Europe which led to the bourgeois revolutions, and the 1850s–1860s in Japan that culminated in the Meiji Restoration. It was Vietnam’s own “decade of awakening,” during which the country’s small intellectual elite, for the first time in Vietnam’s history, began working on:

- Modern nationalism (three concepts of “quốc sử”, “quốc ngữ”, “quốc văn” [“national history,” “national language,” “national culture”] wrapped in the concept “quốc hồn” [“national soul”]).

- A historical view inspired by Herbert Spencer’s social evolutionism conveyed through Japanese and Chinese “tân thư” (新書, meaning “new books.”) This perspective identified Vietnam’s national defeat by the French as stemming from a broader gap in civilization—not simply military technology, but also education, culture, and spiritual advancement. This historical view became the spiritual driving force that motivated the need for national development throughout the 20th century, although sometimes due to historical circumstances, this need was partially submerged.

- Awareness of individual human beings and human rights.

- The first appearance of notions such as gender equality, women’s rights, and recognizing women’s individual worth. These ideas were even facilitated by the colonial republic, which financed a newspaper called Nữ Giới Chung (“Women’s Awakening Bell”), edited by Sương Nguyệt Anh, daughter of Nguyen Dinh Chieu, a symbol of anti-French patriotism in South Vietnam in the 19th century.

- Recognizing a national spirit of citizens (“quốc dân”), cultivating the consciousness of “citizen” concerning the nation, replacing the consciousness of “subject” owned by lords, kings, or the feudal court.

- Developing core republican concepts such as judicial independence, separation of powers, rule of law, separation of religion and government, and respect for the autonomy of science and education.

- Discovering the scientific spirit in exploring nature, society, and humanities. The objective view of things from a technical perspective first appeared in historical studies, literature, education, and journalism.

- Formation of a culture of debate and ideological exchange. This decade witnessed an explosion of public discourse. The technical perspective of looking at things appeared in historical studies, literature, education, and journalism for the first time.

- In parallel with the rise of republican ideals, the 1920s also saw an emergent criticism of communism—even before communism had fully taken root in Vietnam. This critical stance predated the formation of communist parties. It thus was not an outcome of direct ideological conflict but rather the result of exploring various possible futures for the nation. Nonetheless, it laid the intellectual groundwork for the ideological battles that would flare up in the mid-20th century.

The generation of the 1920s poured all its intellectual energy into Phan Chu Trinh’s three-part slogan: “Khai dân trí” (enlighten the people with Western ideas of progress), “chấn dân khí” (imbue the people with the spirit to transform themselves, their society, and the world forcefully), and “hậu dân sinh” (provide conditions for the people’s prosperity).

4. Pluralistic History and Contemporary Vietnam

Viewing communism as the primary ideology of 20th-century Vietnam—and reducing modern Vietnamese history to an armed independence struggle in which communists played a pivotal role—forces most studies of modern Vietnamese history to downplay or overlook the importance and even the presence of republican-oriented social movements and political entities. As a result, these studies are unable to account for or logically explain the real evolution of Vietnam’s social forces and the historical upheavals they experienced.

From a political science perspective, official historical accounts attributing modern Vietnamese history solely to one political organization (namely, the Communist Party of Vietnam) cannot accurately analyze contemporary political and social developments.

Studying Vietnam’s republican heritage not only clarifies the trajectory of modern Vietnamese political history; it also helps restructure the history of education, media, and cultural, literary, and artistic trends in 20th-century Vietnam, allowing for recognition of differing perspectives and the variety of social groups and ideological leanings.

Reference:

Lovett, F. (2018). Republicanism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Summer 201). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/republicanism/

Whitmore, J. K. (2019). Communism and history in Vietnam. In Vietnamese Communism in comparative perspective (pp. 11-44). Routledge.

Phan, C. T. (2009). Phan Châu Trinh and his political writings (Vol. 49). SEAP Publications.

Vu, Tuong and Nguyen, Thuy. “Chapter 1 “Doi Moi” but Not “Doi Mau”: Vietnam’s Red Crony Capitalism in Historical Perspective”. The Dragon’s Underbelly: Dynamics and Dilemmas in Vietnam’s Economy and Politics, edited by Nhu Truong and Vu Tuong, Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2022, pp. 25-50. https://doi.org/10.1355/9789815011401-003

Trần, V. G. (1996). Sự phát triển của tư tưởng ở Việt Nam từ thế kỷ XIX đến cách mạng tháng tám 1945. Tập 1. Hệ ý thức phong kiến và sự thất bại của nó trước các nhiệm vụ lịch sử.

Nguyen, Thuy. “Vietnam’s Strategic Thinking during the Third Indochina War.” (2021) The Journal of Military History 85 (1), 285-86.

Vu, T., Nguyen, T., & Nguyen, L.-H. T. (2024). Vietnam in the Reform Era. In P. Asselin (Ed.), The Cambridge History of the Vietnam War (pp. 353–379). chapter 16, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Huỳnh, K. K. (1986). Vietnamese Communism, 1925-1945. Cornell University Press.

You may like

Translation: The Decision in 2013 of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Certain Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform

Thủ Đức Demonstration High School: A Modern Educational Policy and Teaching Method of the Republic of Vietnam

Southeast Asia falls into China’s Trans-Asian Railway Network

A Proposed Outline for a Study on Republicanism in Modern Vietnamese History

Tran Le Xuan – Diplomatic Letters

Vietnam’s unresolved leadership question

Rethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

Democracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

Pandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

US-VIETNAM REVIEW

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoVietnam’s unresolved leadership question

-

Politics & Economy2 years ago

Politics & Economy2 years agoRethinking History and News Media in South Vietnam

-

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago“The Vietnam War Was an Unwinnable War”: On Factuality and Orthodoxy

-

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years agoDemocracy in action: The 1970 Senatorial elections in the Republic of Vietnam (Part 1)

-

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years agoPandemics and Morality: Lessons from Hanoi

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoThe Limit to U.S.-Vietnam Security Cooperation

-

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years agoNational Shame: How We (Americans) can learn from Nguyễn An Ninh

-

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years agoUS-Vietnam Partnership must Prioritize Vietnamese Education