Thuy Nguyen and Tuong Vu

Download pdf

Abstract

This essay examines the organizational structure and influence of the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP), focusing on its four central offices—the Central Party Office (CPO), the State President’s Office (SPO), the Office of Government (OG), and the Office of the National Assembly (ONA). These offices coordinate the functions of the Party’s highest leadership and government bodies, reflecting the overlapping roles of the Party and the state. The essay explores the limited public access to government financial data, highlighting the Vietnamese government’s strategy of controlling public finance information to maintain its authority.

Keywords: Vietnamese Communist Party, public finance, governance

The Offices of the “Four Pillars”

The Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) is not only the ruling party in Vietnam but is also the only political party that exists legally in this country of nearly 100 million people. As in other communist countries, the VCP’s domination is written into the country’s constitution. There is no law that bans the formation of political parties but the authorities would arrest and imprison anyone who attempts to challenge the VCP’s monopoly.

The VCP distinguishes itself from the government in principle but not in practice. One such practice is the Party’s use of government revenues from Vietnamese tax-payers for its own expenses without any public supervision. The total expenditures of the Party to conduct Party-only businesses are a secret, but they must be a huge drain on the national budget. There are perhaps tens of thousands of Party bureaucrats out of 4 million Party members. They run Party organizations that are extended alongside the government bureaucracy throughout society.

At the national level, a Central Party Office (CPO) coordinates Party business under the direct supervision of the Politburo and the Secretariat. The Head of this Office is a member of the Secretariat whose official rank is higher than a government minister. The General Secretary of the VCP is considered one of the four “pillars” of the regime in Vietnam. The other three “pillars” include the State President, the Prime Minister, and the Chair of the National Assembly. The Secretary is primus inter pares among the four.

Like the Central Party Office (CPO), three other offices play the same role for three remaining government “pillars,” including 1) the State President’s Office (SPO) to coordinate the business of the State President and the Vice President; 2) the Office of Government (OG), a ministerial-level agency under the Prime Minister; and 3) the Office of the National Assembly (ONA) to serve Chair of the National Assembly, Vice-Chairs, the Standing Committee and other Committees, and the Ethnic Council of the National Assembly.

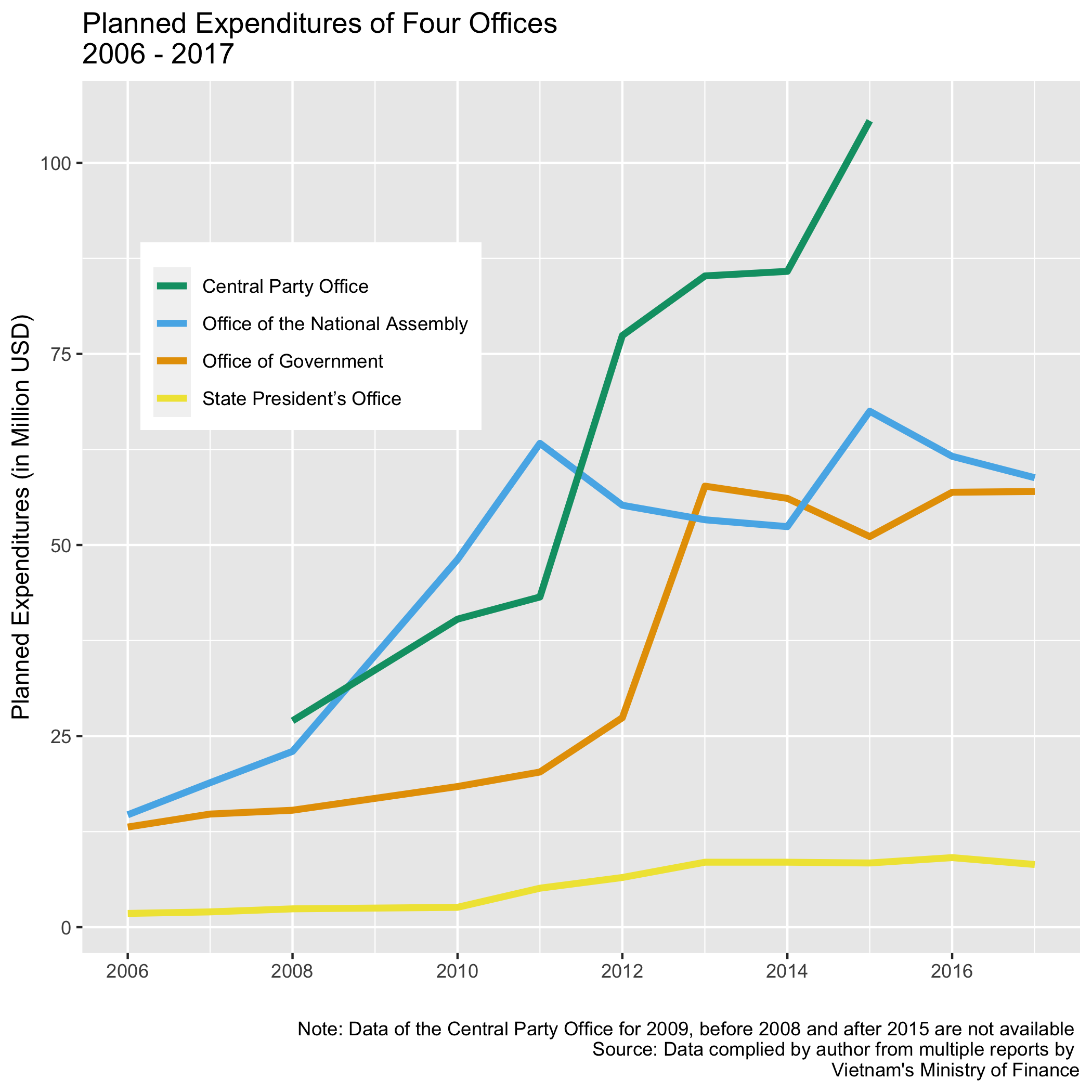

Since the Prime Minister oversees the most activities of the government, one would expect the Office of Government (OG) to have the largest budget among the four. But this is not the case. As Vietnam’s national income has increased at the rate of 5-7% in the last decade, one also expects the budgets of all four agencies to increase; yet our data shows a pattern of uneven increase under the leadership of the VCP’s General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong since 2011.

The Party Chief’s Mixed Record

Mr. Trong has been more influential than his two immediate predecessors, Mr. Le Kha Phieu and Mr. Nong Duc Manh. In his second term, he launched an anti-corruption campaign that netted more than 110 high-ranking officials.[1]

Yet success did not come smoothly. Mr. Trong failed in his first attempt to launch an anti-corruption agenda in 2012. Despite his recommendation, the Central Committee of the VCP refused to discipline then-Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung for his role in the bankruptcy of several large state-owned conglomerates.

Notwithstanding that prominent failure, Trong successfully re-established two important Central Party Commissions, including the Economic Commission and the Interior Commission in 2013. Both Commissions had been folded into the Central Party Office since 2007.

The Economic Commission was now tasked with overseeing the state-owned enterprises many of which were hotbeds of corruption under the leadership of Prime Minister Dung. The Interior Commission was to be primarily responsible for the investigation of graft cases involving high-ranking officials.

Yet, Trong encountered resistance again with the VCP’s Central Committee in 2013 when he recommended Mr. Vuong Dinh Hue and Mr. Nguyen Ba Thanh, the two new chairmen of these two Commissions, for membership in the Politburo. The Central Committee did not vote for them but elected other candidates, meaning their power would be limited.

As part of his strategy to fight corruption and promote state-owned enterprises, Trong entrusts the CPO with the task of watching over the party branches in those enterprises.[2] By his second term as General Secretary (since 2016), Trong was able to get key allies elected into the Politburo, including Mr. Vuong Dinh Hue, Mr. Tran Quoc Vuong, and Mr. Pham Minh Chinh (Mr. Thanh had died earlier of illness).

It has turned out that the Economic Commission failed to assume any larger role and became a kind of halfway house for corrupt officials awaiting discipline such as Mr. Dinh La Thang and Mr. Trieu Tai Vinh.[3] In contrast, the Interior Commission has been an effective player in the anti-corruption effort under the leadership of Mr. Phan Dinh Trac, a former Police Colonel. Mr. Trac is widely tipped to be elected into the Politburo at the next Party Congress.

Where Have All the Money Gone?

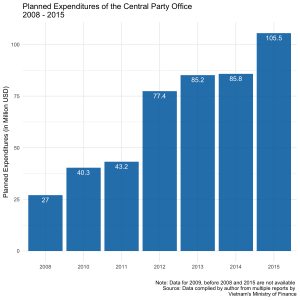

When we examine the budget of the CPO, we also found evidence of a more active Trong.[4] The actual expenditures are not available, but the planned expenditures of the CPO show an increase of 4 times in 7 years between 2008 and 2015, from nearly US$27 million (VND 622 billion) to about US$105 million USD (more than VND2400 billion).

A remarkable change, namely a sharp increase of nearly 180 percent of planned expenditures for the CPO, took place between 2011 and 2012 right after Nguyen Phu Trong became General Secretary. This was in contrast with the earlier much sharper increase of the Office of the National Assembly (ONA)’s budget during 2006-2010.

With that increase, the budget for the CPO in 2012 was almost three times as high as that of the Office of Government, or more than twice higher than the combined budgets of the Office of Government and the Office of the State President. Although the budgets of other offices also rose, they bottomed out after 2014 while the budget of the CPO continued its sharp rise in 2015, when data on its spending ceased to be available (See the top figure).

The mixed record of Mr. Trong captures the ongoing internal tension at the apex of the VCP. He has done much to shore up the power of his office by reviving key Party Commissions and expanding the CPO’s budget. This helps reverse the trend of the previous decade when the pillar of the General Secretary shrank and was in danger of losing significance vis-à-vis the other three.

Whether his successor can sustain Mr. Trong’s work is an open question. With Mr. Trong’s failure to empower the Economic Commission for more effective control over state-owned enterprises, the challenge awaits the next Party Chief to fight for his own political relevance.

Limited Public Access

Meanwhile, the Vietnamese government is intensifying its regulation and monitoring of information, particularly when it comes to accessing sensitive areas such as public finance. The government’s approach reflects a broader strategy to maintain control over critical data that could expose inefficiencies, corruption, or mismanagement within the state apparatus. Access to public finance documents, such as government budgets, expenditure reports, or state-owned enterprise audits, remains extremely limited and often opaque, making it challenging for independent researchers, journalists, and the general public to obtain reliable and comprehensive information.

This tight control over financial data is not merely about maintaining secrecy; it is a calculated move to prevent scrutiny and accountability. By restricting access to such documents, the government aims to minimize the possibility of public criticism or organized pressure for greater transparency. This opacity creates a significant barrier for independent watchdog organizations, NGOs, and scholars who attempt to assess and evaluate the government’s financial practices, ultimately curtailing the potential for meaningful oversight.

Even when public finance documents are available, they are often incomplete or heavily redacted, with only selective information released to the public. Government agencies may issue reports that provide broad, generalized figures but omit crucial details about specific expenditures, debt levels, or allocations to controversial projects. These sanitized versions of financial data are designed to project an image of competence and control, while concealing the full extent of financial decision-making processes and the possible misuse of public funds.

In addition to restricting document access, the Vietnamese government also closely monitors individuals and organizations attempting to investigate or report on financial matters. Journalists and bloggers who write about public finance issues, especially those hinting at corruption or mismanagement, are subject to harassment, intimidation, or arrest under broad and vaguely defined laws against “anti-state” activity. Authorities use these laws to target and suppress voices that call for greater financial transparency, labeling them as threats to national security or stability. As a result, many journalists self-censor when reporting on economic and financial matters, knowing that any perceived criticism could result in severe repercussions.

Notes

[1] Nhan Dan, July 2020

[2] See Decision 80-QĐ/TW 2012 here

[3] Mr. Thang was an oil executive and member of the Politburo before his fall from power in 2019. Mr. Vinh was Party Secretary of Cao Bang province who first gained notoriety for nepotistic practices and who was implicated in a scandal involving cheating in the national graduate examination in 2018.

[4] The State Budget Code System, issued in 2016 by the MOF’s Decision 324/2016/TT-BTC, lists the CPO’s spending under the “Central Agencies” chapter, together with the other three offices, besides ministries and state-owned companies. Although the general annual reports of the planned expenditures are posted for most agencies, the line on CPO is not always made available to the public.

Reference:

Nguyen, T. (2019, October 7). Government’s monopoly of information – How Vietnam chased away a top downloaded app in a day. Uoregon.edu. https://usvietnam.uoregon.edu/en/governments-monopoly-of-information-how-vietnam-chased-away-a-top-downloaded-app-in-a-day/

Ministry of Finance (2017). Mof.gov.vn. https://ttcg.mof.gov.vn/webcenter/portal/btcen/pages_r/l/newsdetails?dDocName=MOFUCM177248

Schuler, P., & Truong, M. (2019). Leadership Reshuffle and the Future of Vietnam’s Collective Leadership. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/ISEAS_Perspective_2019_9.pdf

Nguyen, T., Tran, H., Nguyen, A., & Van, T. (2016). Community participation in rural water supply: a case study in My Hoa–Tra Vinh. Journal of Science and Technology, 54(4B), 178-184.

A View of the Vietnamese Communist Party’s Internal Tension through the Budget of the Central Party Office

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

Society & Culture5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

ARCHIVES5 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Politics & Economy1 year ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

Politics & Economy5 years ago

After 19751 year ago

After 19751 year ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago

Politics & Economy4 years ago